Click here to read more from our November 2016 issue

THE HISTORY:School results have been getting better—especially for the poor Nobody disputes that more pupils in England have been passing exams in recent decades. And nobody who has looked at the results in any detail can dispute, either, that the rise in GCSE success has been especially marked among pupils from poorer homes. As the chart shows, their pass rate has shot up from just 23 per cent, for children born in the mid-1980s, to 65 per cent for the mid-1990s generation.

But what critics of England’s mainly comprehensive schooling system can and do dispute is whether this apparent progress is an illusion—the product of “grade inflation.” There is some evidence—for example from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study—that overall performance has not climbed as rapidly as raw exam results would suggest. But the same PISA data has been used to demonstrate that the attainment gap between rich and poor has narrowed since 2000, so this closing of the gap looks real.

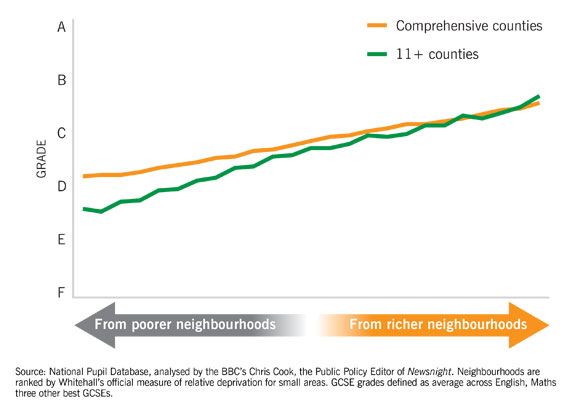

Across most of England, the two-tier grammar/secondary modern system was abolished during the 1960s and 70s, with either no grammars at all or only the odd one or two holding out in most councils. But the continuation of an 11-Plus system in a few counties—Kent and Medway, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire—constitutes a natural experiment. Its results are clear on the chart. On average, GCSE results are lower in the 11-Plus counties, which is why the green line sits below the orange. Furthermore, because the results here are arranged by the relative deprivation of the neighbourhood from which each pupil comes, we can see that the penalty for living in a grammar school county is sharpest for the poor.

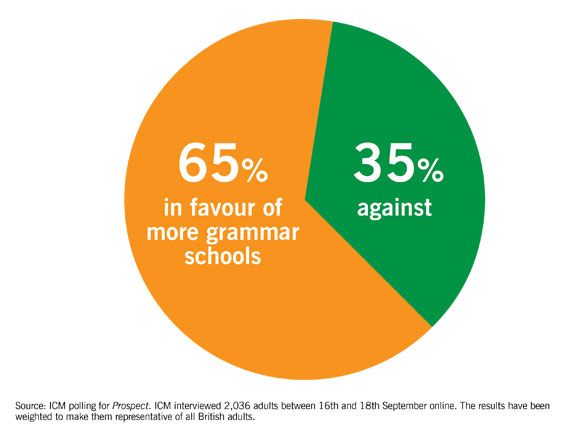

The statistics are clear: grammars do nothing for social mobility. But maybe statistics can never compete with individual stories of working class lives, turned around by an 11-Plus pass. ICM polling for Prospect suggests, voters are split 65 per cent to 35 per cent in favour of grammar schools being set up “wherever a significant number of parents” want one, even though the question was worded to highlight that it would fall “to other non-selective schools to accommodate all the children who fail” to win a place. Near identical majorities applied when we asked voters about grammars in their own town (64 per cent approval) and allowing existing secondaries to become selective (63 per cent). There was a majority across every English region, age bracket and social grade, and support was actually higher (67 per cent) among parents with kids aged under 16 than others (64 per cent). Number crunchers are left wanting to send their fellow citizens back to school.

THE HISTORY:School results have been getting better—especially for the poor Nobody disputes that more pupils in England have been passing exams in recent decades. And nobody who has looked at the results in any detail can dispute, either, that the rise in GCSE success has been especially marked among pupils from poorer homes. As the chart shows, their pass rate has shot up from just 23 per cent, for children born in the mid-1980s, to 65 per cent for the mid-1990s generation.

But what critics of England’s mainly comprehensive schooling system can and do dispute is whether this apparent progress is an illusion—the product of “grade inflation.” There is some evidence—for example from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study—that overall performance has not climbed as rapidly as raw exam results would suggest. But the same PISA data has been used to demonstrate that the attainment gap between rich and poor has narrowed since 2000, so this closing of the gap looks real.

Across most of England, the two-tier grammar/secondary modern system was abolished during the 1960s and 70s, with either no grammars at all or only the odd one or two holding out in most councils. But the continuation of an 11-Plus system in a few counties—Kent and Medway, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire—constitutes a natural experiment. Its results are clear on the chart. On average, GCSE results are lower in the 11-Plus counties, which is why the green line sits below the orange. Furthermore, because the results here are arranged by the relative deprivation of the neighbourhood from which each pupil comes, we can see that the penalty for living in a grammar school county is sharpest for the poor.

The statistics are clear: grammars do nothing for social mobility. But maybe statistics can never compete with individual stories of working class lives, turned around by an 11-Plus pass. ICM polling for Prospect suggests, voters are split 65 per cent to 35 per cent in favour of grammar schools being set up “wherever a significant number of parents” want one, even though the question was worded to highlight that it would fall “to other non-selective schools to accommodate all the children who fail” to win a place. Near identical majorities applied when we asked voters about grammars in their own town (64 per cent approval) and allowing existing secondaries to become selective (63 per cent). There was a majority across every English region, age bracket and social grade, and support was actually higher (67 per cent) among parents with kids aged under 16 than others (64 per cent). Number crunchers are left wanting to send their fellow citizens back to school.