On holiday, Brits are often reduced to pointing and repeating the question a little louder. Expectations have long been so low that we’ve ceased to feel embarrassed about our lack of fluency in foreign tongues; even so, the rate at which we are now dri?fting towards out-and-out monolingualism should be cause for alarm. Among young people, the basic proficiency afforded by studying a language through to GCSE at 16 is falling away—total entries have been plummeting since at least the turn of the millennium, with no end in sight.

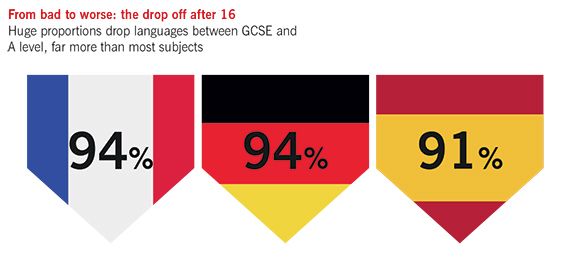

Take French: since 2000, entries have plunged by 63 per cent. The drop in German is even starker and increases elsewhere, most notably in Spanish, do not nearly compensate. The post-16 picture is even grimmer, with a uniquely low proportion of GCSE students carrying a language over to A level. While 38 per cent stick with chemistry and 20 per cent with history, just 6 per cent carry on with French.

The big fall long predates Britain’s current withdrawal from Europe, so what’s to blame? According to Teresa Tinsley, who compiles the annual “Language Trends” survey, the problem can be traced back to New Labour’s decision to allow children to drop languages before GCSE.

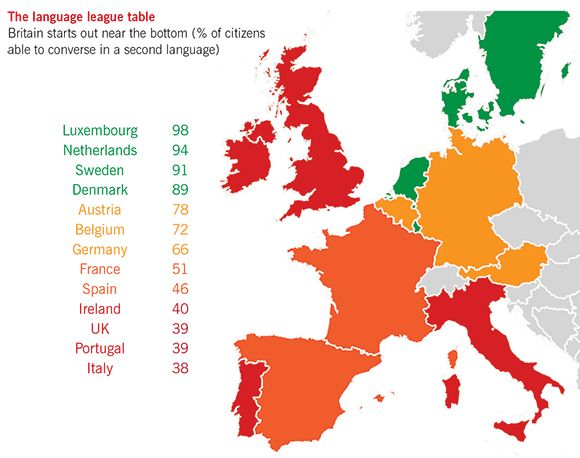

Britain already sits near the bottom of the European league table—just 39 per cent of UK adults can speak a second language compared with 98 per cent in Luxembourg—and, the way things are going, we’ll be even more tongue-tied on holiday in future.