Inter-generational inequality in data. Photo: PA

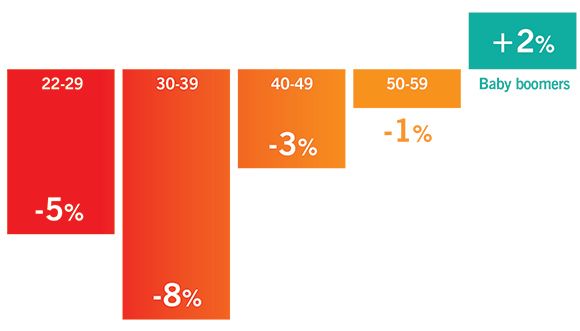

The financial crisis was a disaster for everyone, but young adults were hardest hit. Those in their twen- ties were the only age group to see a pay squeeze of over 10 per cent. Ten years on, as they head into their thirties, this group still has the most ground to make up.

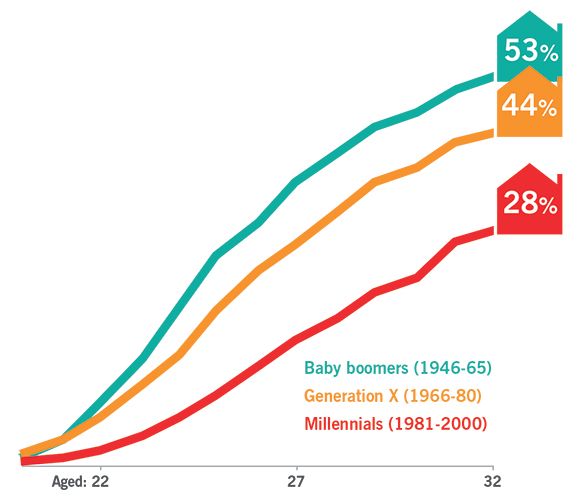

Even before the crisis, the young were slipping behind their parents in important respects, with home-ownership in particu- lar slipping out of reach. Britain’s post-war baby boomer generation thrived by buying young. But it’s become much harder since— millennials today are half as likely to own their home by 30 as their parents’ genera- tion. Meanwhile, commute times are on the up for the young. High rents and prices seem to be pushing them further away from work.

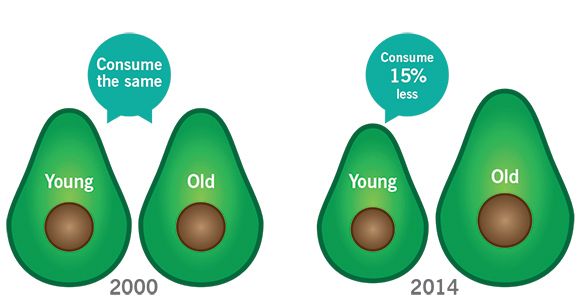

Grumpy boomers may suspect this is all down to feckless youth blowing their cash on fancy phones, holidays and meals out. But in fact, if anyone’s burning through extra cash it’s older generations. At the turn of the cen- tury young adults and older workers spent more or less the same. A decade and a half on, the young were spending 15 per cent a week less than those approaching retirement. Those lazy clichés about avocados should be toast.

Youth clubbed

The slump hit the pay packets of the young hardest—and the recovery has been weaker for the under-40s too

Later on to the ladder

Millennials are half as likely as boomers to have bought a home by the age of 30

Pushed out

By 40, millennials look set to spend three extra days a year commuting to work compared to boomers at that age

Make do and spend

It’s not the young that are splurging on holidays and lunches out. The 25-35s used to consume the same as the old, but post-crisis the 55-65s spend 15 per cent more