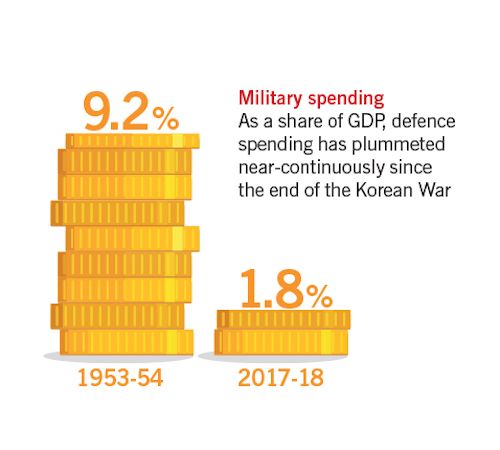

After Theresa May’s £20bn “birthday present” for the NHS, defence secretary Gavin Williamson was mocked for claiming he could “break her” if she didn’t find £20bn for the armed services too. Behind the macho posturing, there is concern in military circles about the depth of retrenchment. It is not new: personnel numbers have been falling ever since the Korean War as spending has been squeezed. The share of national income devoted to defence has dropped by four-fifths since 1953; meanwhile, its share in total public spending fell from 23 to 5 per cent. If our forces still buy the latest kit, they can do so only by buying less—with, for example, sharp cut-backs in the number of tanks and various types of aircraft and naval vessels.

The 1950s were, of course, another world: National Service, the colonies and the Cold War. The passing of each of them justified cuts. But after 1990, outsourcing picked up pace. The UK could, explains Trevor Taylor of Rusi, wage the first Gulf War “overwhelmingly with uniformed people, but by the close of operations in Afghanistan in 2013-14, the MoD was using as many contractors as soldiers.” Service chiefs who wish it were otherwise can point to plenty of threats. But they face a tough battle against schools, social care and hard-pressed taxpayers. Even if they prevail, the British forces will still not be what they once were.