The government has lost its majority in parliament, so it is unlikely to be long before there is a general election. In the 2017 ballot the Conservatives attracted the most Leave voters while Labour was most popular among Remain voters. So what has changed in the party preferences of Leavers and Remainers, and with what implications for the next election?

The Conservatives lost many of their Leave voters to the Brexit Party at the European elections this year largely because of the government’s failure to deliver Brexit on schedule. At the same time, frustrated with the ambiguity in Labour’s position, many Labour Remain voters switched to the Liberal Democrats or Greens.

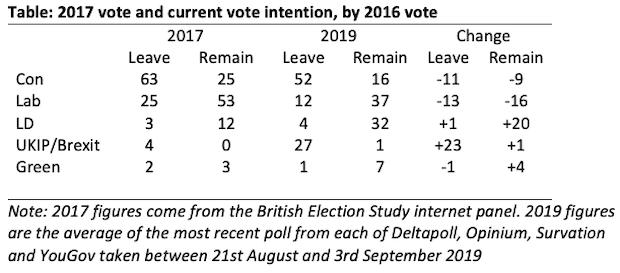

Since May (the month and the leader) the challenger parties have waned and the two main parties have recovered somewhat, but Westminster vote intentions are still closer to the multi-party competition we saw in the Euro elections than they are to the two-party dominance of 2017. The table shows how Leavers and Remainers voted two years ago, and how they intend to vote now. The rise of the Liberal Democrats and Greens has been largely confined to Remain voters, while the Brexit Party has, unsurprisingly, only really attracted those who voted Leave.

What is perhaps more surprising is just how much both main parties have suffered setbacks from both sides. Labour has fallen back almost as much among Leavers as it has among Remainers. While the largest outflow from Labour in absolute numbers is among Remain, in relative terms, labour has lost just under a third of its 2017 Remain voters, but as much as half of its former Leave voters.

Meanwhile, far from simply losing Leave voters to the Brexit Party, the Conservatives have lost almost as many Remain voters, mainly to the Lib Dems. Again, although similar absolute numbers of Leavers and Remainers have deserted the Tories since 2017, they have lost just one in six of their Leave voters, but more than a third of their Remain voters. Now, among Labour “vote intenders,” Remainers outnumber Leavers by roughly three to one. Conversely, those who now say they will vote Conservative are roughly three to one on the Leave side.

This all has obvious implications for the political positioning of the two main parties. But I imagine anyone who has read this far is keen to know how many seats each party would be projected to win. I hesitate to provide the figures because they are not a forecast! Much could change in overall levels of support for the parties between now and the election, as it did spectacularly in the 2017 campaign. Also the polls could be wrong again.

That said, the projections, whether by traditional uniform change or taking Leave and Remain voting patterns into account, give the Conservatives 320 seats, a similar tally to the 318 they won last time, and enough for them to govern with the Democratic Unionist Party. The Conservatives’ increased lead over Labour (up from three points at the 2017 general election to seven points in recent polls) might not yield a majority, but it would hurt Corbyn’s party. Labour is projected to lose over 30 seats, mainly to the Conservatives. Those Tory gains would be offset by losses to the Liberal Democrats and SNP, which are projected to increase their tallies to 31 and 48 respectively. The latter figure already incorporates eight SNP gains from the Conservatives, but some might expect the loss of Ruth Davidson to further harm the Tories’ fortunes north of the border.

To secure a majority the Conservatives are trying to win over Brexit Party supporters. If they succeed in winning them all, Boris Johnson could be returned with a majority over a hundred.

It will be difficult for Remain voters to coordinate to stop them. Tactically avoiding the flow of Labour votes to the Greens and Lib Dems in Labour-Conservative marginals is not enough. Nor is additional Labour to Liberal Democrat tactical voting in Conservative-held Lib Dem targets; the Labour vote was already squeezed in those seats in 2017. If Brexit Party supporters rally behind the prime minister, it would take unprecedented levels of tactical voting by Labour and Lib Dem voters in favour of the other, and all perfectly coordinated across constituencies, to prevent a Conservative majority.

On the other hand, if the opposition-supporting Remain voters do succeed in tactically coordinating in this way and the Brexit Party support holds up, the Conservatives would be reduced to fewer than 230 seats and Labour would win a majority, albeit a modest one of 30.

Tactical coordination among Leave voters would be more politically effective because of the more even geographical distribution of the Leave vote. While the Remain vote is more concentrated in Scotland, London and some big cities, there are small Leave majorities in most seats. Overall, while Leave won 52 per cent of the vote, it is estimated to have won 64 per cent of constituencies. So long as those who did not (or could not) vote in 2016 continue to turn out at low rates, Leave voters can win big majorities under first-past-the-post if they can coordinate on a single party to represent them.

Not only is coordination among Leave voters more effective given the electoral geography, but politically it looks easier. Polls consistently show that Brexit Party supporters are much better disposed to Johnson than Liberal Democrat supporters are to Corbyn, or for that matter Labour Party supporters to Jo Swinson. There is perhaps still greater indifference between Labour, Liberal Democrat and SNP supporters in Scotland to each other’s parties.

The leaderships of the opposition parties might currently be able to coordinate on how their MPs should vote in parliament on the timing of the election. Whether they can coordinate on how tactically their supporters should vote at the polls is another matter.

The danger for Remain voters, and others concerned about the possibility of a no-deal Brexit, is that the parties they support might attract only Remainers. In particular, for Labour the route to majority government depends on winning back Leavers as well.