For decades political parties have competed furiously for one of the great prizes of British politics: the affections of the swing voter. It wasn’t that long ago that there were relatively few political swingers: until the 1990s, fewer than a quarter of voters would switch parties from one election to the next.

Yet that once relatively rare breed is becoming increasingly common, which means party campaigners are going to have to come up with new tactical thinking. The British Election Study survey panels, conducted episodically over the last fifty years, are unique in that they are able to track the same voters from one election to the next, unlike more conventional opinion polls that only look at a snapshot of voters at a given time.

Using these studies, you can identify the percentage of voters who switch their vote from one party to another between each pair of elections since 1966 when such data was first collected.

In 1966 only around 13 per cent of voters had changed their minds since the previous election in 1964. Since then, the proportion of swingers has been steadily increasing. By 2015, 43 per cent of voters backed a different party to the one they supported in 2010.

The increase in swing voters is pretty consistent. The three exceptions are between February and October 1974, when the short eight month gap between elections left little time for switching to take place, between 1997 and 2001, when the electoral dominance of New Labour under Tony Blair held back the tide for a time, and finally in 2017, which still saw 33 percent of voters switch parties (the second-highest figure on record) despite only two years having elapsed since the previous vote. 2017 also saw the highest recorded level of switching between Labour and the Conservatives.

29 years of party people A lot of vote shifting can go on even between elections where the overall result remains stable. In 2001, for example, more people switched votes than in any election before 1997, with a surprising level of turmoil beneath the surface stability. While these largely cancelled out on that occasion, it set the stage for more dramatic changes in the parties’ votes later on.

So British voters now seem more likely than ever to jump from party to party. But who exactly are these swingers? Are they disillusioned former party loyalists? Or have British voters simply stopped getting into a serious relationship with the parties in the first place?

We can get some insight into this using data from the yearly British Social Attitudes Survey, looking at the number of respondents who say that they do not identify with any of the political parties (party identifiers tend to switch much less often) when they are asked ‘Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a supporter of any one political party?’ and then ‘Do you think of yourself as a little closer to one political party than to the others?’ if they say no to the first question.

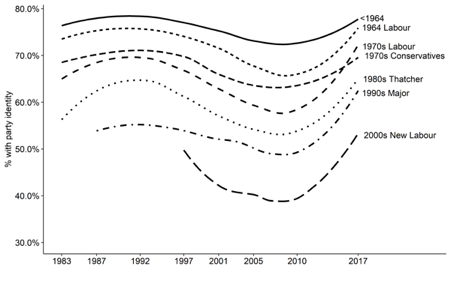

The graph below combines data from 1984 to 2013. Each line represents people who first were eligible to vote under a different government. Higher lines mean that there are more people who identify with a political party. So, for instance, voters who came of age before 1964 started with very high levels of identification (77 per cent), which have stayed mostly constant ever since. Most of the lines on the graph fell in the 2000s, which shows that almost all generations fell out of love with the parties during the New Labour years, although there has been a small recovery since then.

However, the small changes in taste for swinging among the older generations is dwarfed by the promiscuity of the younger generations—shown by the dashed lines—a large proportion of whom never form an attachment to a party at all. Each generation in the data has been less committed to the parties than the previous generation was at the same age, with only around 50 per cent of the youngest generation—those coming of age under New Labour—expressing attachment to any political party.

Party identification by age cohort

Since most of this change has been a generational shift, it may be a long road back for the parties. Loyalty to parties is often handed down in families, with children inheriting their parents’ commitment to a party. Now that this process has broken down, and younger generations have lost their attachment to parties, they may in turn pass on this political detachment to their children.

The majority of younger voters have simply never grown up with the idea of getting into a long-term relationship with a political party, so they may never settle down.

Swinging when we’re winning?

If Britain’s newfound taste for swinging isn’t going to disappear any time soon, what does it mean for party competition?

In the past most people had settled partisan views, which seldom changed. General elections could be won by attracting the relatively small group of voters who hadn’t made up their minds and could very easily vote for either of the two main parties, so political parties based their strategies around mobilising their core voters and targeting the few waverers.

While they worried about traditional loyalists not turning up to the polls, the parties could be assured of their supporters’ votes as long as they got them to the voting booth.

The electorate is not entirely losing its taste for long-term relationships in politics, though. While voters’ attachments to parties are weak, their attachments to sides of the EU referendum are stronger than partisan identity ever was. But these new identities make for much more uncertain election outcomes. While party attachments tended to keep voters faithful, referendum attachments can just as easily pull voters away if another party makes a better offer.

Nowadays, swing voters are no longer a small section of the electorate who are being pulled back and forth by the parties, but a substantial chunk of all voters. This helps to explain why politicians have been so surprised by the sudden rise of new parties competing for groups previously thought to be reliable supporters.

The new parties that have entered British politics have also allowed voters to express their views on issues that don’t fall neatly into traditional left-right politics such as immigration (UKIP) or Scottish independence (the SNP). This in turn has posed a dilemma for the traditional parties, who are pulled in multiple directions trying to stop their voters being tempted away.

This may just be the start. If the number of swing voters stays this high, the parties will have to get used to defending themselves on multiple fronts.

This is an extract from Sex, Lies and Politics, published this month, by Biteback