A half-moon shone over the English Channel, the water was calm and the air cold. In the early hours of 14th December 2022, an inflatable boat drifted from the shallows of a Calais beach into deeper waters. Ibrahima Bah, a young asylum seeker wearing a blue and black puffer jacket and a trucker cap, clutched the tiller and looked back to shore. He could see the shadowy outlines of the agents—people smugglers, human traffickers, opportunists, whatever you want to call them—who had arranged the journey. They watched the boat depart before disappearing into the night. Ahead of him, Bah had been told, were the lights of England. That was the direction he was expected to drive in. And—according to his account—if he did not, he would be killed.

Bah, a Senegalese teenager with a round face and button nose, was not alone on this boat. Though the inflatable vessel was just seven metres in length, at least 43 fellow migrants were seated ahead of him. Most were young men, but a dozen children were on the boat, too. Many were from Afghanistan but there were others from Sudan, India, Uzbekistan and Albania. Bah says he had only one friend on board: 18-year-old Allaji Ba, from Guinea. The others had been largely unknown to each other until they were bundled into a car with its seats stripped out, about 15 at a time, and driven from their camp at Dunkirk to the beach. Yet amid the criss-cross of dialects, a nervous buzz of anticipation tingled between the passengers, who believed that their final destination was near.

Tickets for this ride averaged €2,000. Bah agreed to drive so that he and Allaji—both penniless—could travel for free. The deal was struck the day before, brokered by someone in the smugglers’ network. But when Bah first saw the undersized dinghy, inflated by hand in the darkness while the agents egged on the migrants with threats, he says he changed his mind. The response, according to his testimony, was a sharp blow to his back, knocking him to the ground. A flurry of kicks—Timberland boots, he says—and the understanding that he no longer had a choice in the matter. Bah says he feared more than a beating; the smugglers carried sticks, knives, and he saw the shape of a pistol in a holster. He was led down to the boat, last to get on board.

At first, all seemed well. The 40 horsepower outboard motor stopped and started, but they made progress. A young Afghan sat at the bow and gave directions from his iPhone, the only navigational device. Excitement was in the air, but fear, too. It was dark. The boat had no lights, no radio, no flares. The sense of isolation grew as the boat propelled into the night, heavy with bodies. It had been sheer luck who managed to get a buoyancy aid in the scramble to board. Bah did not, nor did Allaji. Perhaps, Bah thought, this was for the best. As he saw it, if something happened, someone might kill you to get a buoyancy aid. He’d rather swim to save himself from drowning than fight.

Thirty minutes passed. Maybe an hour. Maybe two. At some point, water began to gather on the floor of the boat. Bah, he says, was focused on driving, while the passengers bailed out the water using buckets. “Keep calm,” he told them. But as the boat charged on, the water began to rise, faster and faster. With it came panic. \

Alone in the darkness, 15km from shore, as freezing cold water scaled their bodies, passengers began making desperate emergency calls. At 2.47am, Kent Police received this plea from an unidentified male. “Hello… I need ambulance, my sister. I am in the sea and I have family, help us help us I have family…”

“Slow down… stop shouting…” the operator replies. “What is it you are trying to tell me?”

“My boat… it fall down… my boat… help us help us help us my friend.”

“Where are you?”

The mobile phone goes dead.

The passengers turned on the torches on their phones and waved them in the air like fireflies. Then, out of the darkness, emerged a fishing vessel. Bah steered towards it, willing the increasingly sluggish inflatable closer. A few men leapt into the water and thrashed their way towards the boat. Some who stayed put began to pray. One wanted to perform the last rites. The others screamed.

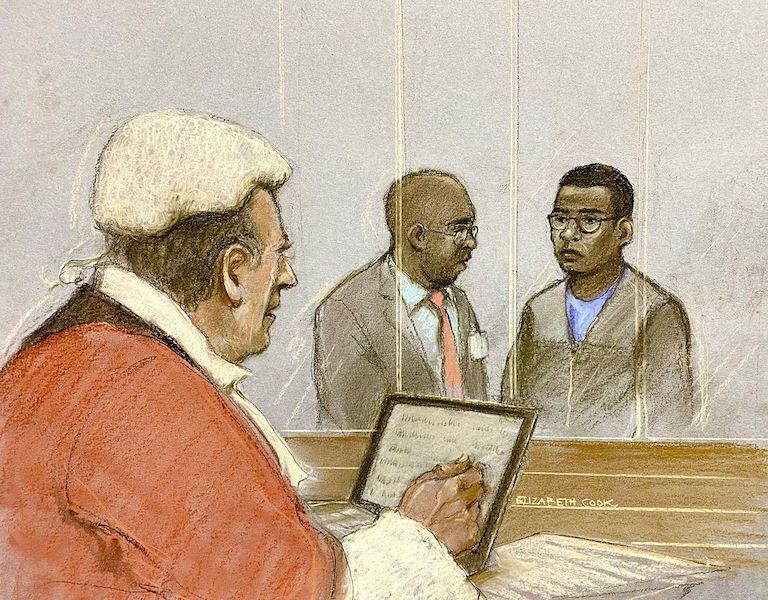

A little over two years later, in January 2024, Bah arrived at Canterbury Crown Court and took a seat in the dock of court six. The building, an eclectic jumble of bricks and glass that overlooks Chaucer Road, is situated in a city renowned as a place of pilgrimage. But for the past two years, it has become the de facto venue for the prosecution of hundreds of “small boat” cases. This one was different, though. Bah was not only on trial for facilitating a breach of UK immigration law, but for four counts of manslaughter—one for each of the bodies retrieved from the sea following the rescue. If convicted, he could face life imprisonment.

Bah’s age remains disputed—a birth certificate suggests he is still only 17—but for the purpose of the trial it was agreed he was 18 at the time of the crossing. Wearing a grey tracksuit and glasses, he nodded along as the indictment was read out, repeated back to him in his native Wolof by a translator who sat beside him throughout the trial. Only one of the four victims on the indictment was named: Hajratullah Ahmadi, a 31-year-old Afghan, who left a wife and a six-year-old daughter. The others were known only by ID numbers. One of them, however, a young man with a missing index finger on his right hand, was known to Bah. It was the body of his friend Allaji.

The boat had no lights, no radio, no flares. The sense of isolation grew

In the public gallery, a handful of supporters—mostly associated with Captain Support, a group that offers solidarity to those accused of driving boats to Europe—looked on nervously. One activist based in Calais had travelled from France to attend. The CPS and the Home Office were also eagerly awaiting the outcome of the highly publicised trial. The case was an experiment in how far the government could push the law in its pursuit of harsher punishments for those who arrive by small boat.

It also shone a light on the moral quandary of a prosecution of this kind. An attempt to convict Bah last summer had reached an impasse when, after a four-week trial and five days of deliberation, the jury was unable to reach a verdict and a retrial was called. Their indecision suggested that, for many citizens, pinning a manslaughter charge on a desperate migrant was too far a stretch of the law. The question for jurors in court six seemed to be not about whether an asylum seeker can be deemed responsible for the lives of those on board a dinghy, but whether he should be.

As Bah had steered through the dark towards that fishing boat, a 24m scallop dredger named the Arcturus, Raymond Strachan, its lean captain, was awoken by a commotion above deck. His first mate, Navine Singh, had flung open his cabin door to tell him that he had just found a man hanging off their landing wire. “Captain, migrants!”

Strachan rolled his window down. Cold air flooded in, and with it the sound of shouts and screams. Strachan told Singh to wake the other crew and raise the nets. Up in the wheelhouse, Strachan could see five more people hanging off the port side. Then he spotted the dinghy, about 30 metres away, in a dire state. When the migrants had spotted the fishing boat many had stood up, causing the weakened floor to collapse. Pashto, Dari, French, English, Wolof; panicked cries jumbled helplessly between the migrants as the boat crumbled like the Tower of Babel. Now it resembled something closer to a rubber ring, or a bike’s inner tube, the two sides folding in on each other, with many migrants trapped in between.

Bah was metres away from his friend, yet unable to reach him

A rope was tossed. Bah caught it and pulled the dinghy close. At this stage, according to his account, none of the others on board were strong enough, but he held it tight while the other men, overcome with panic, clambered over one other, desperate to escape into the fishing vessel. Five, 11, 16 aboard. Singh called out the count as the sodden figures were dragged to safety.

Bah was still sitting on the partially inflated side of the dinghy, but Allaji was in the water now, weighed down by his clothing. He couldn’t get a hand to Allaji, but he says he had hauled two others out of the water. There were about five men left in the dinghy by the time Bah himself boarded the Arcturus, according to his account. Shivering and in shock, the migrants were sent below deck for a hot shower, biscuits and Pepsi. They wrapped themselves in duvets, bedding and the crew’s spare clothes.

Some, though, were still thrashing in the water, encircled by the remains of the collapsed dinghy. Allaji was among them, struggling and gasping for air. Strachan saw Bah on deck, crying out and waving his arm in the direction of the water: “Save him,” Bah said. “He’s my brother.” Bah was metres away from his friend, yet unable to reach him. Ropes were thrown, but it was too late. Bah could see it with his own eyes. Allaji had drowned.

An hour ago, there was only darkness. Now this remote spot in the English Channel was abuzz with activity. The opaque water was illuminated by the lights of rescue boats and three helicopters that circled low in the sky. RNLI lifeboats from Dover, Hastings and Dungeness had arrived, as well as a French navy vessel and a coastguard ship, the HMS Severn. The Arcturus, with 31 migrants on board, was ordered to take its passengers to Dover. As its engine whirred into motion, a man’s body attached to the ship by a rope drifted to the surface, as if even in death he hoped he might make it to England. The crew could not bring themselves to handle a corpse. A Naval response vessel was called to retrieve it, but by then the unidentified man was lost to the sea.

Below deck on the Arcturus, Bah lay on a padded seat and slept. As they swept towards English shores, rescue boats searched for remaining survivors. Eight more men were pulled to safety, and the four bodies of those who had drowned. It was still dark when the Arcturus reached Dover. Bedraggled, confused and in shock, the arrivals were given a health check and food, before being taken to Manston Immigration Centre to be processed. There, through an interpreter and without a solicitor, Bah was asked to give his account of the journey. Two days later, he was arrested.

When he was rescued, Bah believed that at least he had made it to safety. Here in the UK, his ordeal was only just beginning. Replying to the officers when he was charged, he said: “I have to say I did not kill anyone.”

Asylum seeker, pilot… killer? Bah’s identity no longer belonged to only him. “I can’t understand what’s happening in England,” he wrote to me from prison, in scrawling handwriting. “But I leave everything in the hands of God.”

Faith has guided him for many years, on a journey that has taken him from a rural village in the Kolda region of Senegal to a cell in HMP Elmley, on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, where he still believes “things will be okay”. He has long felt hardship. When Bah was three years old, his father, a farmer, passed away. After that his mother struggled to support him and his four sisters. Bah moved to live with his uncle in the Gambia and, as a child, he left school to seek employment as a metal worker. “His intention was to help the family,” one of his sisters, Hassanatou Ba, who lives in Morocco, told me. “He didn’t want to see us struggling.”

Bah would occasionally visit his family on weekends or for festivals. He liked football and to sing with his friends. “We called him ‘the singer’,” says Hassanatou. When Bah decided to attempt to reach the UK, he called his family from the Gambia to let them know. His sister was scared but also proud. “Because when you hear that your only brother decides to travel in order to have a better future to help the family, to me, that’s a source of pride.” They never had the chance to say goodbye in person.

From the Gambia, Bah travelled to Mali then to Algeria and Libya. While navigating a route through a country roamed by gangs and militia, he was kidnapped. The ransom was beyond the means of his family and Bah was held captive for seven or eight months, during which he was forced to do manual labour such as building work. If there was resistance, he would be beaten badly, he says, and when he was not working he was kept in confined conditions and underfed. Thousands of migrants crossing Libya are forced into slavery, subjected to violence or sexual abuse, according to Amnesty International. Those who can, push on to Europe.

Hassanatou sent me a video that she says the family received from the kidnappers. It shows Bah standing by large cooking pans. The barrel of a rifle points towards him, as if held by the person filming. Bah stands up; he looks meek and afraid. Another photo she shared showed Bah’s hand wrapped in a bandage. It had apparently been hit with an iron. In another letter, Bah told me that he escaped when taken out to wash plates. “I found a person and asked for his help,” he said. “He gave me some clothes and shoes. Some of them helped like brothers. They gave me 20 dinars [about £3] to pay the taxi to go to the capital.”

Finally free from his captors, though traumatised, Bah secured a crossing from Libya to Italy on a smuggler’s ship. For four days and nights, the overcrowded boat drifted over the Mediterranean, a sea that has claimed the lives of up to 30,000 migrants in the past 10 years.

At times during this journey, while the driver rested, Bah would help steer. Eventually, the boat was picked up by rescue services and brought to Sicily. Travelling by road and fare-dodging on trains, he moved up through Europe and went west, from the arid lands of the southern Mediterranean to Bordeaux, meeting Allaji along the way. From there, he joined the thousands of other migrants who gather in makeshift camps at Dunkirk, poised to cross; the White Cliffs of Dover barely 30km away.

While Bah was crossing North Africa, the British government was coming up with legal innovations to crack down on small boats. Since 2018, the number of migrants crossing the Channel by such means had risen rapidly—partly due to an intensification of policing of other modes of transport, such as train or lorry—and the Conservative government, eager to promote secure borders and controlled immigration in a post-Brexit Britain, was determined to appear tough. The notion of a nautical invasion, however pitiful, holds particular potency for those who like to believe Britain still “rules the waves”. Boris Johnson, the prime minister at the time, put it bluntly: “We will send you back.”

“Stopping the boats” soon became a political battle cry. Yet as the reasons driving migration—war, famine, economic precarity—persisted, so the boats floated on. Between 2018 and 2021, the number of arrivals by small boat rose from 299 to 28,526, according to the Migration Observatory. In 2023, it was more than 45,000. Despite the increasingly hostile political commentary, 92 per cent of these arrivals claimed asylum and of those who have had their claim processed, 86 per cent have been granted refugee status or similar.

Human rights groups say that one way for the government to reduce the small boat crossings would be to establish alternative safe routes or expand humanitarian visas and resettlement schemes for asylum seekers (as it has done in a limited capacity for Syrian and Afghan refugees). Instead, the government has resorted to prosecuting those on board. Initially it made use of Section 24 of the 1971 Immigration Act in order to bring criminal proceedings against people for illegal entry, and Section 25 for those deemed responsible for “facilitating” illegal entry: the pilots.

One of the first to be convicted in the UK was an Iranian asylum seeker named Fouad Kakaei. Although he was not a smuggler profiting from the trip, and the steering was shared among the 10 asylum seekers on his boat, Kakaei was sentenced to two years and two months’ imprisonment. The conviction was successfully appealed on the basis that while unauthorised entry was illegal, unauthorised arrival with the intention to claim asylum was not. After all, once someone arrives, if they are to claim asylum, their entry has become lawful. Kakaei now has refugee status in the UK.

Undeterred, the home secretary at the time, Priti Patel, sought legislative changes to overrule this perceived loophole and punish refugees who arrive by irregular means. The Nationalities and Borders Act from 2022 conjured up a new offence, “illegal arrival”, and increased the maximum sentences for such breaches. It is at odds with the 1951 Refugee Convention, which recognises that many asylum seekers may depend on irregular means of arrival. And in its determination to make such convictions possible, the government effectively criminalised the process of claiming asylum. This is because a person can still only claim asylum in the UK once they are physically here, but there is no visa category an asylum seeker can apply for in order to “arrive” legally to do so. This Kafkaesque trap carries severe consequences for those caught in it. Illegal arrival can now be punished with up to five years in prison. Facilitating illegal arrival—piloting a boat, for example—can result in a life sentence.

At the start of Bah’s trial, I met Victoria Taylor, a researcher at Oxford University, who has observed more than 100 court hearings relating to small boat crossings. “It is quite scary how easily the law is able to criminalise people seeking asylum for the act of seeking asylum,” she says. Taylor describes how these people, often traumatised and confused, are hurried through a system of which they have little understanding. “They are pleading guilty 48 hours after arriving in the country, being remanded in custody for six months, then are brought out for their sentencing hearing and often released soon after with no accountability mechanism.”

Data collected by Taylor found that, in the first year alone, 240 people were charged under the new rules (either for “illegal arrival” or “facilitation” and 172 were convicted. The cases of those charged were often deemed to have an aggravating factor, which could be as menial as having previously applied for a visa, or, as with about half of them, they were seen to steer the boat. Two people were charged with facilitation for bringing their children with them. The vast majority, like Bah, have ongoing asylum claims. This, however, does not provide protection from prosecution or a defence in court if charged.

Taylor found that those piloting the boats were often young and from poor nations, and they usually agreed under duress or to get a free ride. Sometimes the task was shared among passengers. But under these rules, it matters not if you were profiting from the enterprise—a hand on the tiller is a smoking gun.

The ‘pilots’ have become a stand-in for the trafficking networks

A few days later at Canterbury Crown Court, I took a seat in the neighbouring courtroom to see a small Sudanese man, Howmalow Mawum-Duop, 22, sentenced to 18 months in prison for piloting a boat. Again, he did not receive payment from the passengers. His pregnant wife was also on the boat. She has since given birth and they are unable to be together. Sudan is riven with conflict—millions have been displaced and nearly every asylum claim made by Sudanese refugees in the UK is granted—yet there are no plans to establish a designated resettlement scheme for people to arrive both safely and legally.

“Tackling people smuggling is one of the highest priorities for the National Crime Agency, and we are determined that individuals who put other people’s lives at risk in pursuit of profit are held accountable,” the investigating officer in Mawum-Duop’s case said in a statement. Indeed, “evil people smugglers” were, as Patel said, the target of her new law. But as Taylor put it, the concept of a people smuggler is proving to be a “malleable bogeyman”. Demonised and legally vulnerable, the “pilots” have become a convenient stand-in for the trafficking networks that the government has failed to control. Could it also hold them responsible for the lives lost at sea?

Shuffling papers in the courtroom, Bah’s defence barristers Richard Thomas and Aneurin Brewer readied themselves for a second attempt to get their client acquitted. Brewer had successfully appealed Kakaei’s conviction in 2021; ultimately that was followed by new, harsher legislation and a signal that the government could lose a battle but was determined to win the war. Thomas, who has defended numerous high profile criminal trials, became involved in small boats cases following the introduction of the Nationalities and Borders Act.

The prosecution’s case was that Bah had knowingly breached immigration law and consequently endangered those on board. A reasonable person, it argued, would see the risks from such a voyage. It also argued that Bah owed a duty of care to the victims, which he breached in an act of gross negligence. The main defence at Bah’s disposal was that of duress—that he was forced to pilot the boat. It was up to the prosecution to disprove this and persuade the jury that his actions had a more than minimal contribution to the deaths.

The defence presented Bah as vulnerable and afraid—no different from the others on board. Bah, it argued, had been assaulted and feared for his life and, in the ensuing disaster, did all he could to save people. To the prosecution, he was an individual with experience crossing the Mediterranean who had brokered a deal with the smugglers, knowing what he was getting himself into.

For the first week or two of the trial, the prosecution called many of the survivors to the stand. Most were young Afghans, small, awkward, hiding in caps and jackets like any teenager. They quietly relived the trauma of that night before the courtroom, mumbling to translators, at times via videolink.

The court heard about their long, lonely journeys across Europe and how their family members had paid for their passage to the UK. The price paid by each varied, but most on board had paid around £1,000 to £2,000, held by a third party and only transferred to the smugglers on their safe arrival. We learned how the smugglers kept putting people on boats until they made it across (and the smugglers got paid). Up to £100,000 was riding on the dinghy that night.

The determination of these migrants to reach the UK—and risk their lives doing so—became apparent. Many of the survivors had already made several attempts to cross; one had tried six times. Journeys would be abandoned if the sea was too rough. One Afghan told the court that, during a previous attempt, the boat had got lost and driven round in circles for 12 hours before the passengers called for rescue and were towed by the police back to France.

Though the survivors were called by the prosecution to highlight inconsistencies in Bah’s account, much of what they said corroborated his narrative. Many feared the smugglers, telling the court that they witnessed the use of threats, violence and weapons. One witness described seeing an African man being beaten and told that he would be in charge of the boat. If he did not get everyone across or he returned, the smugglers said, he would be shot in the head. Another recalled a similar scene, of an African man being kicked, slapped and forced onto the boat.

But the prosecution, led by Duncan Atkinson, cast doubt on Bah’s claim that he was beaten. When Bah received a medical assessment after the rescue he had no visible injuries—though he did report to the nurse that he ached all over his body. A photo taken of Bah, sleeping on the Arcturus, was presented to the jury as evidence of a lack of bruises. Bah, Atkinson said, willingly put himself in a potentially dangerous situation and should have expected a degree of pressure.

And by driving the boat, Atkinson argued, Bah knowingly endangered the passengers. He said that Bah had made a choice not to turn back and deliberately ignored the rising water, missing opportunities to act in the best interest of those on board. One witness testified that when the water began to rise, Bah had joked: “I will take you there or I will kill you all.” But another praised Bah’s actions for guiding them to the fishing boat: “He was an angel who saved us.”

At the outset of the trial the judge, Jeremy Johnson, reminded the jurors to put aside the emotions of this charged debate. Yet the politics of immigration inevitably bled into the courtroom. Raymond Strachan, the captain of the Arcturus who can be credited with saving dozens of lives that night, was a key witness for the prosecution. After days of difficult-to-follow testimony delivered through translators, the court was enlivened by a chipper Scotsman and some back-and-forth over nautical terminology.

“And what part of the Channel is the Eastern Channel?” inquired Atkinson.

“Eh?” retorted Strachan with his thick accent. “The east.”

At one point Strachan described Bah as disrespectful, ordering his crew around as if he, not Strachan, was the captain. “He was one of the most arrogant and obnoxious guys I’d ever met,” Strachan told the court, recounting an interaction in which Bah demanded a cigarette from him.

“I said ‘I don’t smoke,’” said Strachan. “He pointed a finger at my face and said, ‘give me a cigarette’ and stamped his feet. I told him to ‘F-off’, I just saved his life. It wasn’t normal behaviour for someone who got their life saved.”

When the coastguard told Strachan to take the migrants to England, he demurred. “I didn’t want to go to Dover,” he said. “I would have gone back to France. But you gotta do what you’re told.”

Bah sat in the dock, listening attentively, as the court flitted through alternating narratives about the role he played that night. Occasionally he would catch the eyes of his supporters and hold a fist to his heart.

After two weeks, he took to the stand. The court heard how he had spent three months living in the Dunkirk “Jungle” before he and Allaji were approached by agents at a spot near a railway where migrants go to charge their phones and collect food from charities. An Afghan man had spotted Bah showing videos on his phone from his crossing of the Mediterranean. Noting he may have had experience on boats, the man is said to have introduced the friends to the agents. If Bah drove the boat, the agent is reported as saying, he and Allaji could travel for free. “I said no problem, we’ll go,” said Bah, but added that the agreement was conditional on seeing the boat first. The agent replied: “Okay, you leave today.”

The prosecution’s cross-examination was bruising. For a day and a half, Bah was asked to clarify every detail of that dark night. What time did they reach the beach? Where was he hit? How did he fall to the ground? When did the water reach what level? Did he really expect them to be rescued once in British waters?

“We were helping each other. It was mutual assistance until we got here,” maintained Bah.

“Other people were helping you, but you were in charge, weren’t you?” Atkinson accused him. Later, he told Bah: “You were the engine of everything.”

Since the case against Bah was first brought, other organisations have scrutinised the events of 14th December 2022. Alarm Phone, an activist organisation that operates a hotline for migrants in distress, highlighted a number of factors that led to the eventual disaster.

It found that despite initial calls for help to the French police, no rescue vessel was sent at that time. And before reaching the Arcturus, the migrants approached two French fishing boats for help and were ignored. According to survivor testimonies, when the Arcturus was finally reached there was further uncertainty as to what would happen next. Some migrants said that the fishermen wanted to call the police to help rather than take the migrants on board. Desperate for rescue, the migrants stood up in a panic, which caused the weakened vessel to collapse. The dinghy had been poorly made: the metal planks for the floor had rubbed against the sides, wearing the material thin.

Concluding its report, Alarm Phone posed some questions. “What if the dinghy had been in the company of a French rescue boat so that people did not feel as if they had to ‘rescue themselves’ or was reached first by an experienced lifeboat crew capable of managing volatile situations to avoid panic and shipwreck? Additionally, why was there apparently no airborne surveillance of the Channel that night, despite the high probability of crossings?”

Aggressive policing in France has caused chaos, panic and death in shallow waters

Utopia 56, a migrants’ rights charity that received a distress call from the dinghy, has filed an involuntary manslaughter complaint against the British and French coastguards for failing to respond fast enough when informed about the unfolding catastrophe. An investigation by the French prosecutor is under way.

Politicians say the punitive measures are designed to save lives—to break the smugglers’ business model. Refugee groups claim the actions of the authorities do more to exacerbate the dangers than reduce them. The UK has committed more than £800m to stopping irregular migration from France over the past decade, yet the tragedies continue. Aggressive policing in France, with officers disrupting or attacking boats as they depart with weapons such as tear gas, has caused chaos, panic and death in shallow waters. While fewer boats now make the crossing, those that do are often dangerously overcrowded. Before 2020 it was rare to have a dinghy with more than a dozen passengers; now they average more than 40.

There’s little evidence that these new offences and the custodial sentences that follow act as a deterrent. This year alone, more than 6,000 migrants have crossed the English Channel, a record high. At least seven have drowned, including a seven-year-old girl. People like Bah think they are claiming asylum and are within their rights to do so. An internal memo from the Home Office has admitted that many asylum seekers have “little to no understanding of current asylum policies”.

Regardless, the government continues to be both creative and cruel; the Illegal Migration Act, introduced in July last year, makes asylum claims registered by those who arrive on small boats “inadmissible”. On 22nd April, parliament passed a bill to have asylum seekers who arrive on small boats sent to Rwanda for processing. Hours after it passed, five migrants, including a child, died in a crush while attempting to cross the Channel in a boat carrying 112 people. Two Sudanese men, aged 22 and 18, and a South Sudanese man aged 22 have been arrested on suspicion of facilitating illegal migration.

By mid-February, Bah’s trial was in its final stages. In Atkinson’s closing argument, he asked jurors to “follow the evidence”. Bah was not the same as the other migrants, he said. They “had indeed chosen to get on board that boat knowing the crossing would be difficult or dangerous but believing they would get there. Their captain, their pilot, their steerer had been appointed in advance”. Once in the boat, Bah was left in control “of it, of them and his fate… all he had to do was return back to shore… as many had done before”.

For the defence, Thomas pitched his case more simply: were the witnesses reliable enough to count on? Or were they struggling to piece together the chronology of a night they would rather put behind them? “Imagine if you were not in the jury box and it was your son or brother in the dock. Ask yourself: would you want them convicted on this evidence?”

Besides, he added: “We all know where the fault lies. With those traffickers who are desperate to make money out of people’s desperation and provided this wholly inadequate boat… This defendant did not kill those four people. He did what he could to save them when the time came. But did he cause their deaths? We say no.”

Throughout the trial, a deeper question had simmered: how much agency or responsibility did Bah really have? The choices at his disposal, according to his evidence, had been stripped away, the agents who exploited him on one side of the Channel, the authorities that were determined to reject asylum seekers on the other.

The jury deliberated for 19 hours. Then they returned to deliver their verdict. Guilty. On the count of facilitating illegal migration, it was unanimous. On the four counts of manslaughter, it reached a majority of 10 to two, finding Bah guilty of gross negligence.

The Home Office was quick to boast of its victory. “The only people who profit from these illegal, dangerous journeys are criminal gangs,” it said in a post on X, despite the fact that no one who had profited from the journey had been prosecuted. Michael Tomlinson, the minister for illegal migration, posted that “If you put lives in danger in the Channel, you will face justice”. But it is hard to see the justice for those who drowned when the person in jail was, for want of a better phrase, in the same boat as they were.

For refugee rights groups, the verdict was “vile”—Bah was a victim, a survivor. In a statement, Captain Support said that the verdict rested on subjective interpretations and the prejudices that can shape them. Bah, it said, was perceived “to be older, more mature, more responsible, more threatening, with more agency, and thus as more ‘guilty’”.

Three days after a verdict was received, we returned to court six for sentencing. In his closing statement, Jeremy Johnson, the judge, acknowledged the hardship of Bah’s life: a difficult childhood, a traumatic journey, forced labour. Once again, the court heard that Bah had not organised or profited from the trip, nor had he coerced or exploited others, as the smuggling gangs often do. As he summarised the case, a sense of futility hung in the air. “What happened is an utter tragedy for those who died and for their families,” he said. “This is also a tragedy for you.”

Bah stood as he was handed a sentence of nine years and six months. Many in the full public gallery hung their heads; some gasped. Bah was led back to his cell. Outside the building, his supporters unfurled a banner: “Free Ibrahima! Borders Kill!”

Leaving Canterbury Crown Court for the last time, I asked a member of his legal team how Bah had taken the news. “Relief,” they told me. “At least he has a number.” Bah, who had already spent more years living in uncertainty than most of us can fathom, now had something firm to cling to; a light on the horizon, even if it was a dim one. After hearing his sentence, he nodded to the judge. “Thank you,” he said.