Boris Johnson may have quit in the whirlwind of the past few days, but the “Global Britain” foreign policy agenda remains.

As Donald Trump arrives for his first visit as United States president, his ambassador to the UK—Woody Johnson—has made no secret that Trump “would love to do a bilateral trade deal.” Many Brexit-supporting MPs and the prime minister herself would see such a deal as a boon to their wider Global Britain agenda.

In her Lancaster House speech Theresa May explained that the referendum “was not the moment Britain chose to step back from the world. It was the moment we chose to build a truly Global Britain.” This analysis has formed the basis of the government’s foreign—and trade—policy agenda since then, so it deserves closer inspection. Did we vote to be more global?

The evidence suggests, frankly, no.

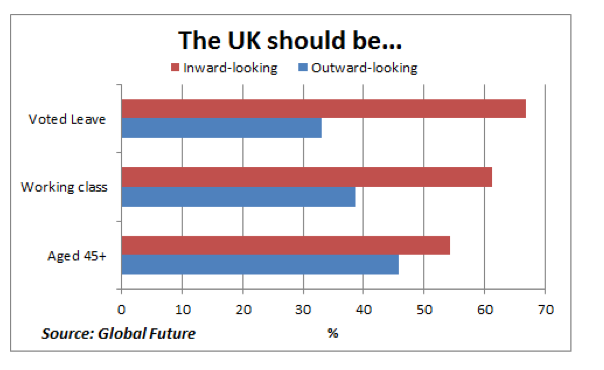

Recent polling by Global Future suggests Leave voters tend to have an inward-looking worldview, as the chart below shows. This means being “focused overwhelmingly on our own national challenges,” which chimes, of course, with wanting to spend extra money on the NHS rather than paying into the European Union budget (although most economists would argue this is a false choice) and being hostile to immigration. So these findings shouldn’t surprise us.

Yet, this inward-looking Brexit is far from the narrative that has been presented by cabinet ministers such as Liam Fox and the recently departed Foreign Secretary. In his major speech in February, Boris Johnson said "Brexit is about re-engaging this country with its global identity.” For most Brexit voters, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Yet even as Theresa May has begun to move her Brexit position towards greater compromise, she continues to pursue the holy grail of an independent trade policy to give shape to her Global Britain ambitions.

But the desire to strike free trade agreements seems, in many ways, to directly contradict the interests of Leave voters. Recent academic work suggests greater openness to cheaper manufacturing imports, from China in particular, was part of a longer-term trend contributing to the decline of left behind areas and increased their tendency to vote Leave. Reducing further barriers to cheaper imports through the pursuit of free trade agreements, though perhaps marginally beneficial at the UK-wide level, would seem a curious way to reward these voters.

The irony of Global Britain is that it probably appeals more to Remain voters than Leave ones. The former might baulk at the individuals leading the charge, but the sentiments of greater global collaboration and co-operation fit better with their worldview, while being out of step with the majority of the Leave constituency.

Recent focus group research by Demos also shows something similar. Voters seem to have a less idealistic view of Britain’s past than the likes of Johnson and Fox, and see its current position in more realistic terms. For them, Brexit wasn’t about rebooting Britain as a global player, in fact it was about recognising we have limited capacities—particularly economically—and that these should be focused almost exclusively domestically.

These current and former government figures in particular appear not to grasp—or rather simply ignore—the priorities of Leave voters when they clash with their vision of what Brexit means. This perhaps partly explains why so many of these voters think Brexit is going badly.

This evidence also explains much on the other side of the Commons too. Labour’s policy strengths tend to be domestic issues, so it is unsurprising both that many of their supporters voted for Brexit in the first place—given their inward focus—and yet also voted for Labour again after the referendum, despite disagreeing with the party line on the EU.

Labour voters expressed an opinion when asked, but the EU was most likely not their primary concern before or after the vote. If one’s priorities are domestic, particularly on the NHS—by far the biggest concern of UK voters after Brexit—housing and education, then according to polling Labour is regularly seen by voters as the better option.

Where the Leave campaign succeeded was in tying together an outward-looking minority—the elite Brexiters—and an inward-looking majority.

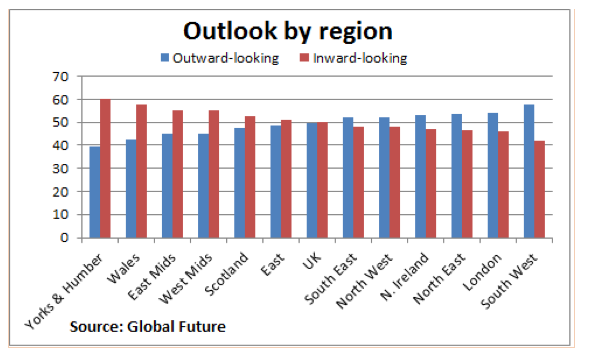

That majority is concentrated in the regions and nations where Labour has historically done best. Former industry-heavy areas such as Yorkshire and the Humber, Wales and the East Midlands have the strongest tendency to be inward-looking, as the chart below shows.

This implies that, for the Conservatives to maximise their Brexit advantage, the Global Britain narrative is precisely the wrong approach if the party wants to make decisive inroads into strong Labour areas.

But both parties face a dilemma in the short term because on this outward-looking measure, as on almost every Brexit-related issue, the country is split down the middle.

The trends for the future, however, seem clearer. As Global Future argues itself, demographic trends suggest that the outward-looking worldview “owns the future,” as these typically younger voters are growing in number whereas older, inward-looking voters are becoming fewer. This is also supported by the work of Rob Ford and Maria Sobolewska at Manchester University, who show that trends in education, migration and age suggest the Remain worldview is likely to get stronger over time.

This misperception about what Leave voters believe in helps partly to explain why Theresa May made such a miscalculation in calling a general election. It was based on false assumptions about the priorities and concerns of the very voters she had aligned herself with. That this strategy remains the same tells us the Brexiters—and May—still don’t seem to know their own people. Or, rather, they want them to be something they’re not.