“We have big plans for the future!” tweeted Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary, after his first phone call with Donald Trump, just hours after the United States presidential election was called. Other far-right politicians were equally ecstatic, from Argentina and Israel to the United Kingdom. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni heralded the “unshakable alliance, common values and historic friendship” between her country and the US.

In fact, leaders of all stripes stumbled over themselves to congratulate Trump and stress their country’s close ties. “I look forward to our close cooperation on the shared interests between the USA and the Netherlands,” said Dick Schoof, leader of the far-right-dominated Dutch coalition. “As the closest of allies, we stand shoulder to shoulder in defence of our shared values of freedom, democracy and enterprise,” chimed in Keir Starmer.

There is little doubt that 2024 was a great year for the far right, a terrible year for incumbents and a troublesome year for democracy around the world. Still, it will not be as impactful as the “annus horribilis” of 2016, which brought Brexit and the first Trump victory. The reason is as simple as it is depressing: as I argued in my 2019 book The Far Right Today, the far right began a process of mainstreaming and normalisation long ago. This past year was not one of political transformation, but rather a product of the political transformation that started at the beginning of the century. You just haven’t been paying attention.

It was trailed as being the “year of elections”. Some 70 countries with a combined electorates of around two billion held elections in 2024; not all of these elections were free and fair, however. In many of the biggest elections, such as those in the European Union, India and the US, the far right did well. Media around the globe bleakly asked whether democracy could survive.

In a surprisingly optimistic assessment, admittedly before the US election, the Economist concluded: “Democracy has proved to be reasonably resilient in some 42 countries whose elections were free, with solid voter turnout, limited election manipulation and violence, and evidence of incumbent governments being tamed.” To be fair, the magazine followed this assessment, clearly foreshadowing the US elections, with the warning: “Yet there are signs of fresh dangers, including the rise of a new generation of innovative tech-savvy autocrats, voter fragmentation and departing leaders trying to rule from beyond the political grave.”

There are many different understandings of the left-right distinction, but I define right-wing ideologies as those that consider social inequalities as good or natural and believe that states should not try to create more egalitarian societies. Within this broad group, the “mainstream” right supports both the core institutions and values of liberal democracy. The far right does not. At its core is nativism, a xenophobic form of nationalism, and authoritarianism, a fundamental belief in order and discipline.

Within the far right, the extreme right rejects democracy—the idea that people elect their own leader by majority (one can think of historical fascism)—whilse the radical right only opposes elements of liberal democracy, notably minority rights and separation of powers. In recent years, however, part of this group has radicalised, for example by undermining the democratic system (like Orbán) or by rejecting election results (like Trump), without openly defending a non-democratic system. These hybrid extreme-radical right parties are best referred to as far right.

If we focus exclusively on the results of far-right parties in parliamentary elections, we see not only that almost all have won in 2024, but also that most have won big. There are two main exceptions. The Bulgarian party Revival contested two parliamentary elections in 2024 and gained almost identical results. More importantly, and surprisingly, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was widely expected to trounce opponents in free and unfair elections it had organised itself, slipped back—but remained in power. Beyond these, there were three small increases for the far right (under 2 per cent) and five big ones (more than 10 per cent), including in France and the UK.

We should add the good results in presidential elections for Jussi Halla-aho, leader of the Finns Party, and Trump as well as the excellent results in the European elections, where far-right parties won roughly one-quarter of the votes and almost 200 (out of 720) seats. Moreover, two of the three largest parties in the new European parliament are of the far right: Marine Le Pen’s National Rally is the biggest and Meloni’s Brothers of Italy (FdI) is the third largest.

Still, while the far right was the only ideological family to win almost across the EU, there were subtle national and regional differences. In some countries, the far right mainly changed shape—for example, in Italy, the overall score remained largely the same, but Matteo Salvini’s League lost most of its voters to Meloni’s FdI. And in most northern European countries, the far right did relatively poorly—notably the Finns Party (PS) and the Sweden Democrats (SD), the two parties that are part of, or support, the national coalition government.

National elections are always national first, but some analysts have put the good results for the far right into a global political context. They noted a “global trend to oust incumbents”, often linking it to (belated) responses to the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War. John Burn-Murdoch, the chief data journalist for the Financial Times, summarised the year as follows: “Economic upheaval + social upheaval = 2024 election results”. This unusually succinct explanation by and large reflects the received wisdom about far-right success in the past four to five decades.

While it is undoubtedly true that the far right profits from economic and political “crises” that create economic anxiety and cultural backlash, it is less often asked why the far right is the only political family to profit from them. Sure, it makes sense that they would be the one to profit from the so-called “refugee crisis”, or even the 9/11 terrorist attack, given the Islamophobic response to it, but it is less clear why it would benefit from the other major crises of the 21st century: the Great Recession, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War. None of these is directly related to the core feature of the far right: nativism, or xenophobic nationalism.

In fact, all three of these crises could equally have led to an increase in support for the (centre and radical) left, given that they all revealed the failures and limitations of neoliberalism. In the case of the Great Recession, this failure was systemic, while both the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War highlighted the problems with the privatisation of key services, such as healthcare and energy, and emphasised the importance of state intervention and planning. And yet, with some exceptions, left-wing parties and politicians have rarely been able to make gains in recent years.

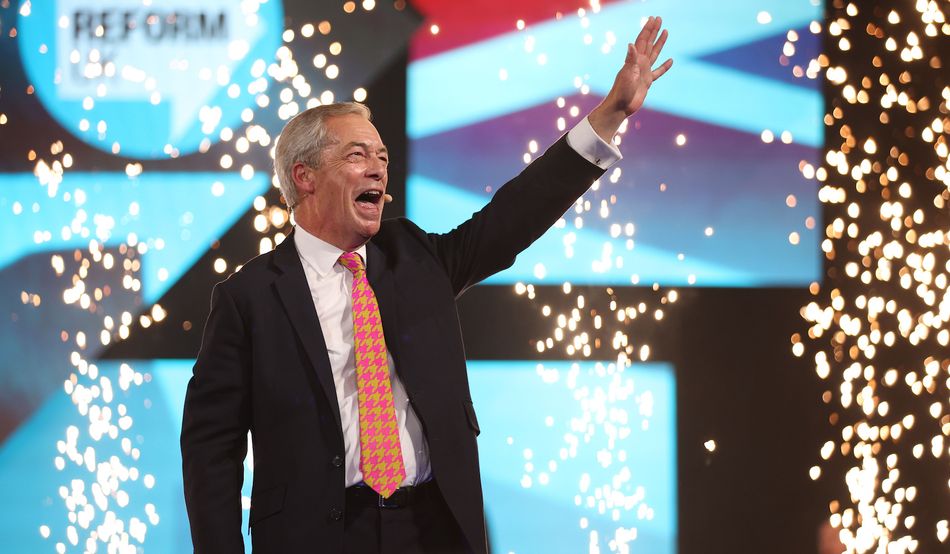

Even in 2024, two of the most celebrated left-wing “victories” were far from impressive. In the UK, Labour won the biggest increase in seats since 1945, but with only 1.6 per cent more votes than in 2019. In absolute numbers, Keir Starmer received more than half a million fewer votes than Jeremy Corbyn did in 2019. And this after more than 14 years of disastrous Tory rule and with the Conservative party at historically low levels of support. Moreover, in electoral terms, the big winner of the 2024 British election was Nigel Farage, not Starmer. Whereas Labour increased its electoral support by only 1.6 per cent, Farage’s Reform gained 12.3 per cent more than his Brexit Party in 2019. Admittedly, the Brexit Party ran in fewer than half of the constituencies, but Reform’s 14.3 per cent even beat Farage’s previous record result with Ukip in 2015—by 1.7 per cent and four MPs.

Similarly, while the French parliamentary elections were celebrated as a victory for the far left and a defeat for the far right, this was mainly the result of our ever-decreasing expectations. Not only did the National Rally become the biggest party by far, but it also gained more votes than the left-wing New Popular Front, an electoral list of a dozen or so parties combined. Just like in the UK, it was the disproportionate electoral system, rather than the voters, that handed the French left a “victory”. In short, even in the few countries where the left won politically, it was the far right that won electorally.

The political shocks of 2016 gave rise to a cottage industry of political doom literature. In 2024, books about the death of democracy and liberalism became bestsellers, while headlines screamed about “the global crisis of democracy”. Some studies seemed to back up the moral panic. For example, the influential V-Dem Project calculated that the percentage of the global population living in a democracy had dropped to 29 per cent in 2021. However, this drop was strongly influenced by democratic erosion in a few populous countries, most notably India. So, is “democracy” really in crisis? And, if so, will it survive what comes next?

As is so often the case, the answer depends in part on how we define democracy (see Table 2). In electoral democracies, the people can elect their representatives in free and fair elections, but they lack liberal protections such as individual and minority rights, which are only guaranteed in liberal democracies. As we can see from Table 2, the number of electoral democracies is still rising, albeit less spectacularly than in previous decades. However, the number of liberal democracies—which is much lower anyway—has been decreasing this century. More generally, people in both democracies and autocracies are facing “autocratisation”. And this is the real story of the 21st century—that liberal democracies are eroding, as so aptly analysed in How Democracies Die by Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, one of the few “democratic doom” books to actually help us understand today’s politics.

In terms of absolute numbers, the many elections of this year have changed little. Although incumbents lost and the far right won in many countries, the regime type of most countries has remained unchanged. In the vast majority of cases, the far right will remain in opposition, while it was already in power in India. That said, the increased strength of the far right, as well as its continued mainstreaming and normalisation, will further weaken minority rights (for groups including LGBT+ people and Muslims) and important institutions (such as the media and universities).

But 2024 did bring one regime change, in the most powerful country in the world. Donald Trump’s return to the White House will affect not just the state of liberal democracy in the US, but also across the world.

First of all, Trump 2.0 will be nothing like Trump 1.0. Whereas his first term was a coalition government with the old Republican establishment, led by Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, Trump will face little political opposition this time around. The party has fallen in line, while the broader conservative infrastructure has mostly radicalised (such as the Heritage Foundation thinktank) and is now competing with a new infrastructure of Trump loyalists (including the America First Policy Institute). Moreover, Trump will preside over a unified government, controlling both houses of Congress, while de facto controlling the Supreme Court too. The main counterweight comes from the country’s strong federalist system, but that only protects people in states controlled by the Democratic party.

Similarly, in terms of foreign policy, Trump 2.0 will be much worse. In his first administration, Trump’s foreign policy position was mostly indifferent rather than a strictly isolationist one. He withdrew the country from some key international agreements, such as the Paris climate accord, and mostly regarded the rest of the world with disinterest. One of the few upsides of this was that, to the great disappointment of other far-right leaders such as Le Pen and Orbán, there was no real attempt to organise a united “global front against liberalism”. Instead, Trump developed “bromances” with an ideologically diverse group of autocrats, including Kim Jong-Un in North Korea and Vladimir Putin in Russia, but was mostly driven by personal financial interest.

Although Trump has now made a few new far-right “friends”—most notably Orbán, whose government has bought influence abroad by channelling vast sums through organisations such as the Danube Institute thinktank—he remains largely uninterested in international politics. But important people in his orbit, and in the Republican party more generally, have become much closer to far-right parties and politicians around the world. There are close ties between the Heritage Foundation and Orbán’s network of pseudo-NGOs, while some high-ranking Republicans have participated in meetings of far-right parties in Europe. Autocrats and billionaires now know how easy it is to manipulate Trump. A “beautiful letter” or a big cheque will buy support and influence, as Kim Jong-Un and Elon Musk have demonstrated. And, completely captured by domestic and foreign authoritarian politicians and “libertarian” businessmen, Trump 2.0 will be even less interested in protecting democracy and human rights around the world.

None of this was inevitable. The rise of the far right and the crisis of democracy are the consequences of political choices, largely by the most privileged people, including the media and political elites. At the micro level, these choices can be explained mainly by arrogance, ignorance and self-interest. But at the macro level, they expose a more problematic structural issue: the limited support for and inherent vulnerability of liberal democracy.

The far right reached its electoral breakthrough before it had been able to build a powerful media infrastructure. For years, the far right and the media were frenemies, who loved to hate each other. On the one hand, many outlets (particularly tabloids) gave sympathetic coverage to authoritarian, nativist and populist viewpoints. On the other hand, far-right parties and politicians complained about the negative coverage from other media, attacking it as “fake news” or even Lügenpresse, but also profited from the disproportionate media attention they received.

As the far right became more mainstreamed, particularly through collaboration and even mergers with the mainstream right, many right-wing media outlets became openly supportive of far-right parties and politicians. For instance, Jair Bolsonaro was supported by many of the major media conglomerates in Brazil, as well as by the Wall Street Journal in the US, while Fox News and a host of newer and more extreme right-wing media voices became mouthpieces for Trump and the radicalised Republican party. Similarly, the free newspaper Israel Hayom, bankrolled at significant financial cost by the American billionaire Sheldon Adelson, helped push Israel further to the right and supported Benjamin Netanyahu, who leads a now far-right government. Vincent Bolloré, the “French Murdoch”, did the same in France with his new media empire.

Obviously, social media plays a role too, albeit not as big a role as is generally assumed. It is true that social media further weakened the role of gatekeepers and has been used astutely by some far-right actors. For instance, Geert Wilders was incredibly effective in setting the political agenda through Twitter, sending a “provocative” tweet in the morning, which was picked up by journalists, who used it to confront mainstream politicians, who would then respond, to which Wilders would respond again in the evening, controlling the whole news cycle of the day.

Moreover, many studies have shown how the far right benefits from “algorithmic radicalisation”, in other words the process by which social media platforms push people down digital “rabbit holes”, exposing them to more and more radical content. That being said, studies also found that social media’s effect on electoral behaviour is relatively modest. Similarly, first impressions are that the impact of artificial intelligence on elections is so far much smaller than was feared.

Of much greater significance is the behaviour of political elites, mostly, but not exclusively, of the right. Just like in Europe in the early 20th century, political elites have played a crucial role in the mainstreaming and normalisation of the far right. After at first largely ignoring or ostracising it, many right-wing parties would co-opt the far right’s message after its electoral breakthrough. And the adoption of its frames and positions, particularly on immigration, made the far right an increasingly logical coalition partner. This can be seen in almost all European countries, including the UK, despite the fact that the far right has so far failed to become a relevant factor in parliament. This notwithstanding, the Conservative party has more or less adopted the framing and policy positions of Ukip and its successors and, although never officially entering into a coalition with Farage, Boris Johnson welcomed his decision not to contest Tory-won seats in 2019.

Elites werenot forced to embrace the far right. They chose to do so

While only a handful of countries had a government that included the far right in the 1990s, the far right is now, or has recently been, part of governments at the national and subnational level in most EU states, as well as a growing number of countries in Asia and the Americas.

These elites were not forced to embrace the far right. They chose to do so, often more for strategic than -ideological reasons, believing that it would ultimately benefit themselves. In most cases, the mainstream elites also underestimated the far right, thinking they could control them. In the case of both Bolsonaro and Trump, there was a strong sense that “the adults in the room” would control the impulsive and incompetent firebrands. A century ago, right-wing elites in Italy and Germany thought the same about Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, with similar results.

The media and political elites often claim that these mainstream conservatives are simply doing what “the people” want. But while it is true that they have long ignored far-right preferences and voices, journalists and politicians often think that “the people” are much more right wing than they really are. They also think that populations have become more right wing in recent years, which is empirically wrong too. The American political scientist Larry Bartels has found that people in the EU and US have not moved to the right. If anything, they have become slightly more inclusive, rather than exclusive. Similarly, while right-wing elites have unleashed a backlash against “Latin America’s Gay Rights Revolution”, there is “no evidence of backlash” among the general population. Again, if anything, people have become more accepting of gay rights. This is not so much because people have changed their opinion, but because more inclusive young people are replacing more exclusive old people (who are dying).

Electorates have, however, changed their focus. Politics was about socioeconomic issues in the 20th century but in the 21st century it is increasingly dominated by sociocultural ones. Simply stated, culture wars have replaced class struggle. Again, this is not a bottom-up process. People follow the elites, who have the power of agenda-setting. Various research has shown that when the media focus a lot of their coverage on specific issues, such as immigration, people will find it more important.

But even when immigration is not a top political concern of the electorate, as in the recent US elections—where it came only sixth for all voters—nativism can drive voting behaviour. This happens when other political issues, including socioeconomic ones, become racialised. Take, for example, the debate about housing in both the Netherlands and the US. In the former, housing was one of the key talking points in the 2023 election campaign, but much of the discussion was focused on the alleged pressure that refugees put on the housing market—while, in reality, only 5 to 10 per cent of social housing goes to refugees in the Netherlands. In the US, the mainstream media highlighted “mass deportations to ease demand” as one of the “housing policies” of Trump’s campaign.

The coming years will undoubtedly see another massive boom in democratic doom literature, and many will look to the past to find the answers for the future. Neither will help us much. To fight the far right and strengthen liberal democracy, we must learn the correct lessons. We are facing neither the far right of the 1980s nor that of the 1930s. Both the far-right threat and the political context are fundamentally different. Consequently, the political solutions will have to be fundamentally different, too.

Timothy Snyder’s book On Tyranny has been at the top of bestseller lists since Trump was elected in 2016. Like other books on fascism and strongmen written by historians, it mainly examines the contemporary far right from the perspective of historical fascism. However, neither the threat nor the political context is the same. Irrespective of whether you believe that we are dealing with the same ideology as before, the contemporary far right is primarily an electoral threat, which historical fascism never was. With some exceptions, most notably Hitler’s Nazi party, fascists were minor forces in elections and only came to power through a semi-coup (Mussolini’s March on Rome) or through foreign occupation, particularly Nazi Germany. Moreover, the political context has fundamentally changed. In the 1930s, democracy was profoundly unpopular and untested. Today, democracy is still hegemonic, even if support is slipping.

The 1980s do not offer us much insight either. Far-right parties then had roughly the same ideology as today—though they were less overtly extreme—but they were mostly poorly organised and leader-dependent, gaining single-digit electoral support. Moreover, they were confronted with a “cordon sanitaire”, as most mainstream parties refused to collaborate with them. Similarly, the media, still largely controlled by mainstream gatekeepers, marginalised far-right actors—even if some tabloids and private television stations were already mainstreaming their positions. Most far-right parties had little ambition to change the system from within, believing it to be an unrealistic goal.

If we look to these two historical periods for lessons to defeat the far right and save liberal democracy, we will find little of use. Historical fascism faced little effective opposition internally and was ultimately only defeated through foreign military destruction in a world war. That is neither inspiring nor empowering. In contrast, the far right of the 1980s was ostracised based on an ideological and moral consensus that is no longer effective. Moreover, it was not so much defeated as slowed down. After all, many of the ideas and parties of that era have become much more widely accepted within the political mainstream.

A strong liberal democracy requires responsibility, of elites and the masses

The only way to protect democracy against the contemporary far right is to understand the far right and democracy for what they are today, not what they were 40 or 100 years ago. At the level of both the elites and the masses, the far right is both mainstreamed and normalised. Democracy is still hegemonic, but liberal democracy is contested.

While the fight against the far right is important, it should not be the end. Rather, the fight against the far right must also, even primarily, be a fight for liberal democracy. It must be positive rather than negative, proactive rather than reactive. It must win over those parts of the elites and masses that either don’t like or don’t understand liberal democracy. And while it would be ideal if this could be achieved purely on ideological and normative grounds, it is important to also appeal to self-interest. After all, liberal democracy is the only system to protect minority rights, and everyone can become a minority at some time.

But a strong liberal democracy also requires responsibility; again, both of elites and masses. Media and political elites should stop neglecting or even rejecting the agency of “the people”. Voters are not “seduced” or “tricked” by far-right politicians. They know who and what they vote for. And even if they did not, it is up to the elites to provide them with enough accurate information.

Liberal democratic elites should not mainstream and normalise far-right actors and ideas. This does not mean that the far right—its actors, ideas, supporters—should be ignored. But because the far right threatens liberal democracy, it should be treated differently than mainstream parties that do support liberal democracy. Far-right figures have largely proven to be bad-faith actors, spreading conspiracy theories and lies; the liberal democratic media cannot simply take them at their word. Rather than publishing opinion pieces or uncritical interviews, the media should critically analyse far-right claims, pointing out the ideological assumptions as well as the factual inaccuracies.

Political elites, on the other hand, should start treating the far right as the voice of the loud minority rather than that of the silent majority. This does not mean that they should ignore the far right’s issues and positions, but neither should they proclaim them to be the main or only concerns of “the people”. The foundation of liberal democracy is pluralism, which acknowledges that societies consist of different individuals and groups that have a variety of interests and values. All these different interests and values are legitimate, and it is up to politicians to find the compromises that satisfy those of a majority of the population. Pretending that there is one best solution for everyone, as both neoliberalism and populism do, not only weakens liberal democracy. It strengthens the far right too.