As Labour’s leadership contest drags on, the temptation to revisit the party’s past is powerful. One place to look is its “wilderness years” of 1979-1997. Yet, Labour has a longer history, and the troubled 1930s are especially riven with striking parallels. Perhaps, then, mournful Labour members seeking inspiration should return to this grim decade?

After all, the 30s opened with an economic catastrophe, swiftly followed by a near-fatal election defeat. Labour had the misfortune to find itself in government when the reapers of the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression crossed the Atlantic. Buffeted by the whirlwind, Labour’s prime minister Ramsay MacDonald reached for orthodox medicine: fiscal retrenchment to defend the gold standard. When this divided his own party, he jumped ship and ran on a “National” ticket with the Conservatives and some Liberals, leaving Labour to crumble to a crushing defeat in 1931. Despite the obvious differences, an existential economic crisis followed by a ringing electoral endorsement of the right will sound familiar to any observer of British current affairs since 2008.

The parallels don’t end there. As in 2019, more working-class electors voted Tory than Labour in 1931 and 1935. To build this hegemony, the Conservatives successfully appealed to newly enfranchised women and the anti-Catholic and anti-Irish vote in Merseyside. But they also appealed to a cross-class patriotism (even asking electors to vote for the “National Government”), and smeared Labour as dangerous “Bolshevists” with dubious links to Soviet Russia.

Moreover, the 30s inaugurated a new era of political economy comparable to the paradigm shift of Brexit. Confronted by threatening global trade wars, the British state shredded old doctrines. Despite first defending both, the state shifted from the gold standard to devaluation and from free trade to protectionism. On both issues, Labour found itself in the wrong place at the wrong time—in a weak and divided minority government during the initial crisis and out of power when new thinking prevailed. Despite these radical transformations, Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin (de facto prime minister in the early 30s and officially from 1935) successfully posed as a bulwark of moderate stability. At a time of rising extremism—with growing support for the Communists and the British Union of Fascists, and vicious street-fighting between them—this was a powerful appeal.

Until the mid-1930s, Labour responded badly. Admittedly, it rebuilt its grassroots base, and individual socialists like Ellen Wilkinson famously joined hunger marches from Jarrow in 1934 and 1936. Yet, as is its habit, after electoral evisceration the party promptly splintered further. Socialists in the Independent Labour Party exited stage left. Others embraced the right, whether that was MacDonald’s National Government or Oswald Mosley’s disturbingly dynamic fascist insurgency, which promised both interventionist economics and ethnonationalism. Even among the loyal, some responded to their last government’s financial derailment by flirting with constitutionally radical politics like emergency powers acts that would enable rule by state decree rather than parliamentary vote.

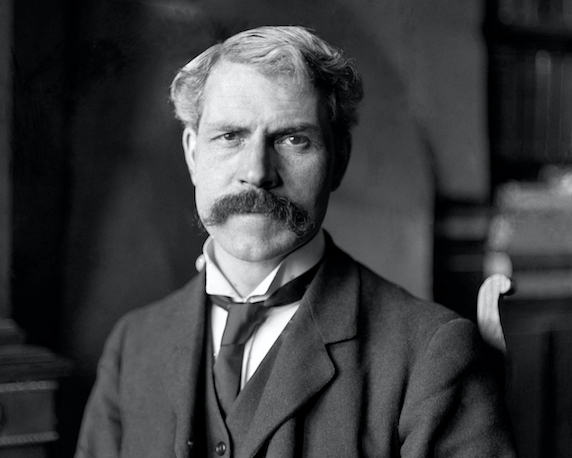

Most resonantly, Labour elected an ascetic, dissenting leader with a strong sense of his own conscience and a history of radicalism in London’s local government. No, not Jeremy Corbyn, but George Lansbury, who became leader of the parliamentary party in 1931 and the wider party in 1932.

If there are parallels, are there any lessons? Perhaps, but those seeking simple analogies, without recognising change over time, should proceed with caution.

Possibly, the 30s demonstrate the importance of plausible patriotism. As historians like Martin Pugh argue, after 1935 Labour repositioned itself as a “national’ party, rather than a “sectional” wing of the organised industrial working class. Crucial was the removal of Lansbury by power brokers like trade unionist Ernest Bevin, and the accession of Clement Attlee as leader. Lansbury’s unflinching Christian pacifism was his downfall: even as Europe descended into darkness, his refusal to support economic sanctions against Benito Mussolini during Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia was the final straw.

From that point, Labour’s leaders carefully guided a party split over rearmament towards support for military action against fascist belligerence. This required some skilful party management. Attlee walked a quivering tightrope between the pacifists and warmongers. He also managed to publicly support the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, while quelling those voices who called for a formal “United” or “Popular Front” with either the Communists or pro-war Tories.

Consequently, the argument goes, Attlee was able to attack the Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement on patriotic grounds. Once appeasement collapsed, Labour’s reorientation permitted anti-appeasement Tories like Churchill to work with Labour in ousting Chamberlain during the crisis of May-June 1940. Labour thus joined a wartime coalition and shed its anti-patriotic baggage.

This nationalist framing of anti-fascist foreign policy was matched by an increasingly “national” turn in progressive intellectual circles. Most importantly, Liberal thinker John Maynard Keynes turned towards a more national economic vision, culminating in his famous General Theory, the ideas of which percolated through left-wing economists like Hugh Dalton, Evan Durbin and Barbara Wootton. Socialist intellectuals also learned from Herbert Morrison’s ideas on London’s municipal socialist public ownership, which provided a model for future nationalisation.

As such, one lesson could be the need for a patriotic and national, rather than sectional, appeal. Indeed, following the victory of the pro-Brexit Conservatives, all of Labour’s leadership candidates seem keen to rebuild Labour’s patriotic credentials. Moreover, Lisa Nandy’s candidacy has revived the importance of “place” and national, regional and local identities.

However, as any historian will say, major divergences between the past and the present make lessons uncertain. Anyone making a serious attempt to draw conclusions from the 1930s must remember two crucial differences.

Firstly, Labour’s 1945 landslide owed much to unique events outside its control. The most important was the Second World War. Labour’s popular support only really grew in the 1940s, when it controlled the domestic war economy through key ministries. Attlee may have read the runes correctly in the late 1930s, but hindsight obscures the risks he took in a dangerous moment.

Secondly, there are the enormous differences in geopolitical might. In the 30s, the UK was a major world power, ruling a sprawling empire (often through brutal force) and disproportionately influencing swathes of the global economy. That is no longer the case. Labour’s leadership candidates today can attempt to construct a programme and personal appeal that enable electoral victory. But they must also stay clear-eyed about the UK’s room for manoeuvre in a world of global hegemons, globalised finance, integrated cross-border manufacturing and the climate emergency. Quite apart from the transformed character of what is now a relatively multicultural and liberal society, any realistic “patriotic” appeal today will look markedly different to the one that Labour championed in 1945.