When the editor of this magazine invited me to look into the House of Lords, my first thought, I confess, was of its comic potential, like something out of Monty Python. It’s hard to overlook the absurdity of a parliamentary body in which no one is popularly elected, lifetime sinecures are awarded to the (literally) entitled and 26 seats are reserved for bishops of the Church of England, who sit together wearing vestments that resemble penguin costumes. From the press gallery high up in the neo-Gothic arches, you look down on a room that resembles a cross between a cathedral and a bordello: opulent red leather benches, a gilded throne, allegorical frescoes on the walls, and the lord speaker presiding from an immense red pillow stuffed with samples from all the wool-producing states of the Commonwealth. Members show off their scarlet ermine cloaks for the opening of parliament, wear their aristocratic titles and honours like bling, and address one another in deferential third-person as “my noble friend”, “the noble and learned lord” or (in the case of the bishops) “the right reverend prelate”. When John Cleese turned down an offer of appointment to the House of Lords in 1999, the California-based Python pleaded an aversion to English winter weather, but I suspect that he feared being unable to keep a straight face.

So caricature is tempting.

But this is not that.

For one thing, as a (mostly) proud American, I feel a little sheepish about my own country’s satire-worthy democracy. Our Congress has been commandeered by a gang of right-wing Visigoths whose party standard-bearer is running for president, again, while under indictment on 91 felony counts, including conspiring to overthrow the election that he lost. And don’t get me started on George Santos, the congressman expelled for fabricating pretty much his entire life history and diverting campaign funds to pay for designer clothes, casino visits and Botox.

America’s glasshouse aside, I’ve developed a soft spot for the Lords. The best case for the upper house—one that will be familiar to British readers—is that it serves as a check, albeit discreet and restrained, on the aggressively partisan House of Commons. Respected jurists who serve in the Lords tell me that they take particular pride in the House’s defence of human rights and civil liberties, areas where the government since the Tony Blair years has often pandered to the right. These days the peers tend to be scornful of the government’s anti-migrant populism and to frown on tough-on-crime posturing, such as the government’s recent promise to sentence more criminal offenders to life without parole. As one Labour peer told me in an email—declining an interview for what she probably suspected would be a takedown of the House—“My priority is using the imperfect institution to fight anti-human rights measures in current dark times.”

Undoubtedly the Lords is ripe for reform, and speculation continues over how far Keir Starmer’s Labour will go in overhauling the House, if it does so at all. According to the latest polling by YouGov, 67 per cent of UK voters say they have “not very much” or “no confidence” in the House of Lords. Then again, 62 per cent say the same about the elected House of Commons, so the polls probably reflect a general mistrust of establishment institutions that is hardly unique to the UK. And while it’s fair to mock the Lords as an anachronism, it’s much less easy to find a consensus on how to fix it.

Philip Norton, a constitutional scholar who is professor of government at the University of Hull and who sits in the upper house as Lord Norton of Louth, says that the lords rarely attract much attention from the press or public—except for the occasional tabloid outrage like the memorable 2009 expenses scandal. “As a late colleague of mine once put it, the House of Lords is the nation’s best kept secret,” Norton told me.

The House of Lords originated in medieval times when kings summoned leading citizens to court to facilitate the raising of taxes. In the 14th century, major landowners and churchmen began meeting separately from local knights and burgesses. Their roles evolved over the centuries, ultimately becoming what you have today, a bicameral parliament, with an elected House of Commons asserting primacy by virtue of its popular franchise, and the appointed House of Lords, with its membership largely drawn from the ranks of government appointees and aristocrats, playing the part of kibitzer.

The House of Lords is an ungainly creature. For starters, there is no limit on its size. Membership today hovers around 800, more than the fixed 650 in the elected House of Commons—and more, as critics like to point out, than any other parliamentary chamber in the world except China’s National People’s Congress. Unlike MPs, the lords draw no salary; they can claim a £342 per diem when they attend, plus some expenses and access to subsidised restaurants. The average daily attendance since 1999 is 417 members.

Most lords are appointed for life by prime ministers after being vetted by the independent House of Lords Appointments Commission. In principle, peers are selected for a diversity of expertise and experience, but prime ministers are not above using the Lords as a reward for party loyalists, campaign donors and other cronies. Boris Johnson, in his three years as prime minister and his resignation honours, appointed around 90 new members to the already bloated Lords, some of whom were easy targets for popular indignation. A stark example is Evgeny Lebedev, a British-Russian tycoon (now wearing the expansive title Baron Lebedev of Hampton and Siberia) whose news media properties had been kind to Johnson and whose father’s career in the KGB reportedly set off a shudder of concern at MI6. In December last year Liz Truss, who served as prime minister for 49 days, bestowed lifetime seats on two architects of the Brexit campaign and her short-lived deputy chief of staff. When Rishi Sunak wanted to call former PM David Cameron back into government in November as foreign secretary, a job that in practice requires a seat in parliament, he simply appointed Cameron to the House of Lords.

It is one of Cameron’s own appointments, Michelle Mone, who currently ranks as the most notorious member of the upper house. The Scottish businesswoman made her first fortune selling a patented backless bra and a second, more dubious fortune supplying protective gear to the NHS during the Covid-19 pandemic. (The propriety of those transactions is being investigated; Baroness Mone is on a leave of absence from the Lords.) In February, Sunak’s government created 13 more life peers, including several Tory campaign donors and the youngest member of the Lords, a 27-year-old former adviser to the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru.

The main job of the Lords is scrutiny. The Commons deals in broad strokes and controls the purse strings, the Lords supplies legislative detail. The lords cannot veto a bill, but they can delay action for up to a year while debating and proposing amendments.

“Most of the time what [the House of Lords] does is make sensible technical suggestions and point out flaws in government legislation, which gets sorted out quietly without anybody noticing,” says Meg Russell, director of the Constitution Unit of University College London. In recent years, however, Russell told me, the lords have pushed back—against attempts to breach international law over the Brexit arrangements for Northern Ireland, and against measures to restrict the right of protest, to cite two notable examples.

Even those who advocate a rethinking of the Lords—and that includes many of the peers themselves—agree that it is valuable to have the Commons second-guessed. The House of Lords is less beholden to party whips, and its committees pay attention to details for which the Commons lacks the time or political will. And while recent decades have seen a growing number of career politicians joining the upper house—about 170 are former MPs—there is still a considerable amount of specialised expertise.

“The people who do the lion’s share of the work bring a variety of experience,” Helena Kennedy told me when we met in a peers’ café near the Lords chamber. Formally titled Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws, she is a barrister and human-rights advocate who has been in the House of Lords since 1997. “People who have been in finance, people who have been judges, people who have been lawyers, people who have been teachers, people who have been university academics or heads of universities, people with medical backgrounds.”

The baroness, a Scottish Labour peer who was raised Catholic, even admits a grudging affection for the 26 Anglican bishops in the House, with whom she has made common cause on criminal justice issues: “People don’t care about prisons,” she told me. “The church does care about prisons.” (“Of course,” she added, “they were terrible on gay marriage,” which passed through parliament in 2013.)

As a (mostly) proud American, I feel a little sheepish about my own country’s satire-worthy democracy

One key to the Lords, says another peer, Ken Macdonald (formally the Lord Macdonald of River Glaven), is that no party has a majority. “If Labour, the Lib Dems and crossbenchers band together, the government can’t get its legislation through, or at least it will be significantly delayed,” says Macdonald, a barrister and former director of public prosecutions who sits in the chamber as a crossbencher. In the Blair and Brown years, a version of this rolling alliance joined forces to resist draconian law-and-order measures, such as a government proposal to let police lock up terror suspects for weeks on end without filing charges, and a move to limit the right to a jury trial. “The more crazy terrorism legislation was fought over at great length in the House of Lords, and most of the worst proposed provisions were knocked back,” says Macdonald.

But on major policy matters, the lords rarely challenge the government head on, implicitly acknowledging that the Commons has an electoral legitimacy the House of Lords lacks. During the battle over Brexit, the lords were much less inclined than MPs to leave the European Union and delivered some notable rebukes to the government. But the Leave campaign had won a public referendum and peers ultimately deferred to the government on the fundamental issue. “The House of Lords played a relatively small role in Brexit, really,” says Russell, who co-authored a book titled The Parliamentary Battle Over Brexit. “The House of Lords never at any point remotely went near trying to avert the referendum result, despite having a more pro-Remain membership than the Commons. It was clearly even more politically unacceptable for the unelected chamber to meddle in a referendum result.” Given that a majority of voters today tell pollsters they think leaving the EU was a mistake, one might wish in hindsight that the Lords had been bolder.

As it happens, the Lords’ assertiveness now faces another test. Many of the noble lordships are strongly opposed to the ruling party’s plan to deport illegal migrants to Rwanda. The scheme was narrowly approved on its third reading in the Commons, but “It hasn’t got a cat in hell’s chance of passing through the House of Lords,” Macdonald predicted when we talked last December.

A week after our conversation, a dozen members of the Lords on the International Agreements Committee gathered around a horseshoe-shaped table in a meeting room off the House floor to undertake their own scrutiny of the government’s treaty with Rwanda. In contrast to the Commons catcalls, the discussion over two days was methodical, meticulous and focused on evidence. The committee members exposed a fundamental contradiction in the government’s logic: on the one hand, Rwanda is such a frightening place that the threat of being deported there is supposed to be a deterrent to asylum seekers washing up in Dover. On the other hand, the government insists that, contrary to the fears of human-rights advocates, the deportees will find a safe haven in Rwanda.

The lords seemed deeply sceptical that the Rwandans would be able to deliver the safeguards promised in the treaty anytime soon. The hearings concluded with a tense but civil questioning of the home secretary, James Cleverly. Then the committee, including four Tory peers, unanimously recommended putting the Rwanda plan on hold. It was, in short, the lords doing their job. (Cleverly told the committee afterwards that his entourage had expected the hearing to be “like watching bear-baiting. They have come to see a blood sport, but you have been very hospitable”. That was the Lords being the Lords.)

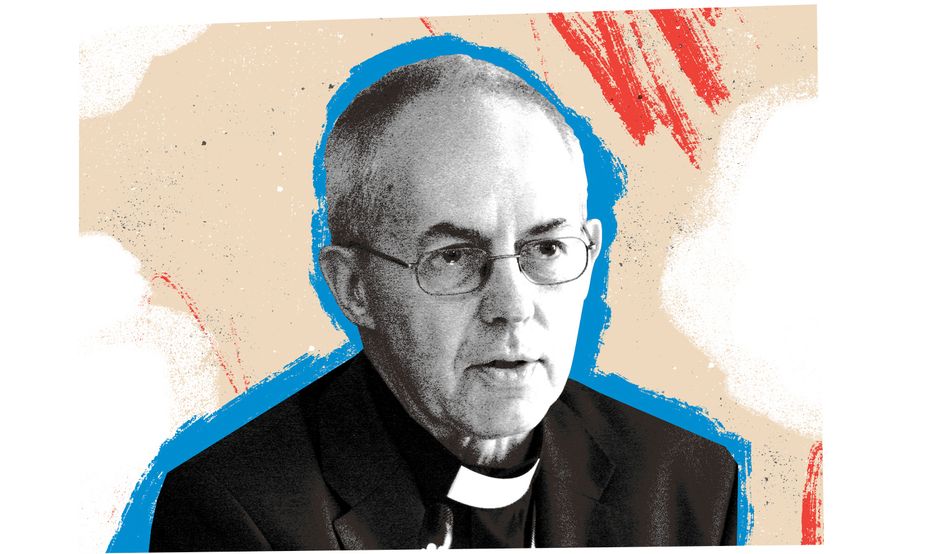

A few weeks later—following four hours of debate and a plea by Baroness Shami Chakrabarti, a Labour peer, for the Lords to be “a little more muscular than usual”—the Lords voted that the government should postpone ratification of the Rwanda treaty. A week later there was a six-and-a-half-hour second-reading debate on the legislation to implement the plan, in which the bill was attacked by dozens of peers, including the archbishop of Canterbury—“the most reverend Primate”—who said the measure threatened “constitutional principles and the rule of law”. Conservative peer and former chancellor Ken Clarke warned against the danger of “moving towards an elective dictatorship”. The breadth of opposition was a setback for Sunak, and threatened to delay any deportations while his plan runs a gauntlet of Lords committee scrutiny and amendment. Sunak had played the legitimacy card, urging the Lords not to try to “frustrate the will of the people as expressed by the elected house”, to no apparent effect.

To understand the House of Lords, I found it helpful to turn from political science to anthropology.

Emma Crewe, professor of social anthropology at SOAS, has spent much of her career studying parliament, stalking and observing the lords and MPs as if they were rival tribes. In her book Commons and Lords: A Short Anthropology of Parliament, she imagines an “anthropologist from another world” surveying the houses of parliament. “She would hear MPs complaining that peers are stuck in the past, out of touch and naive about politics, while peers would regret MPs’ bad manners, tribalism and lack of proper work experience.”

While you might expect a house originating with the aristocracy to be patriarchal, Crewe found the Lords actually has a more egalitarian and collegiate culture than the Commons. Being more advanced in life—the average age in the Commons is 50, in the Lords 70—and not obliged to seek re-election, they are less driven by personal ambition and more open to compromise.

The peers, moreover, “work in an intimate and crowded end of the Palace of Westminster,” Crewe writes, adding, “The close physical proximity of peers—who share offices, have few or no staff and are confined to a far smaller part of the Parliamentary Estate—ensures regular contact.” She likens the ambience in the Lords to a Quaker town meeting. “The House of Lords seems to be the happiest tribe alive while the House of Commons may be among the most unhappy,” Crewe concludes.

To an American, two features of the House of Lords are glaringly alien: the hereditary peers and the bishops

I have spent a few afternoons toggling between the simultaneous live TV broadcasts of the Lords and Commons, and the experience confirmed for me Crewe’s portrayal of the different cultures. The Commons was usually a heckling match, whipped into alignment by party enforcers, the speeches aimed at scoring partisan points and perfecting soundbites for social media, the prospect of compromise remote. In my first week as a parliament-watcher, the Commons mostly exchanged insults over the Rwanda scheme. The lords, while awaiting the Commons’ passage of the Rwanda bill, spent their afternoon question periods in a civilised interrogation of the government, touching on issues ranging from the plight of autistic children confined in mental health hospitals, to companies circumventing Ukraine war sanctions, to the regulation of cannabis-based medicines, to the risks posed by artificial intelligence, to reducing the sugar in school lunches, to light pollution from low-orbit commercial satellites interfering with the work of astronomers.

The discussions were sometimes absorbing, like graduate seminars in which everyone has done their homework. Many of the speakers seemed to know what they were talking about, and to listen to one another with genuine curiosity. I can assure you that the debate is rarely so constructive in either house of Congress in the US. Especially recently.

Since the early 20th century, reforming the House of Lords has been the subject of innumerable bills, commissions, white papers, manifestos, party platforms and scholarly treatises.

To an American observer, the two features of the House of Lords that are most glaringly alien are the hereditary peers and the bishops. The American revolution was in part a repudiation of landed aristocracy and established religion, values later enshrined in our Bill of Rights if not always observed in practice. In the House of Lords, the contingents of Anglican bishops and hereditary peers have been reduced—the former in the mid-19th century, the latter more recently—but vestiges remain. (The UK is one of only two states to reserve a place in the legislature for clerics of the established religion, the other being Iran.) The House of Lords Act of 1999 abolished automatic inherited seats in the Lords, but left a remnant of 92 hereditary peerages in place. The arrangement was supposed to be temporary, awaiting a second stage of reforms that still hasn’t happened. For now, when one of the 92 dies or retires, the vacancy is filled not by an heir but by an arcane system of byelections. Any among the country’s hundreds of dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons is eligible to compete for the open seat (including some women—but male primogeniture largely remains in force). The outcome is usually decided by a vote of the remaining hereditary peers belonging to the party or group of the departed member.

Last September, for example, 13 candidates offered themselves to fill two crossbench vacancies created by a death and a retirement. Their campaigns appeared to consist mostly of brief statements citing their qualifications and pledging to actually show up for work. The two triumphant new lords, one a director of a large veterinary group and the other a family law barrister, are presumably worthy fellows, but they were elected to lifelong terms by a grand total of 23 votes. A spokesman for the independent Electoral Reform Society saw the exercise as evidence of “the ongoing absurdity of the current House of Lords”. It’s hard to disagree. (The UK is one of two countries on earth that still have hereditary seats in their legislatures. The other is the tiny southern African nation of Lesotho.)

Norton describes the landscape of reform proposals in four alliterative categories: “retain” (the House remains fully appointed, perhaps reduced in size and with tighter restrictions on the prime minister’s patronage), “reform” (some, but not a majority, would be popularly elected), “replace” (the chamber would be mostly or entirely elected) and “remove” (abolish the Lords altogether and have a unicameral legislature, as a majority of countries do).

Between 2021 and 2022, Norton himself introduced a private bill that falls more or less in the retain camp, strengthening the independent role of the Appointments Commission in nominating life peers, shrinking the House to be no larger than the Commons, forbidding any party from having a majority of seats and reemphasising the importance of diverse professional experience. The bill was well-received in an initial debate in the Lords.

A more radical replace option emerged from a Labour commission chaired by Gordon Brown, which published its report in late 2022. It would dramatically downsize the Lords—potentially to as few as 200 members—and repurpose it as an “Assembly of the Nations and Regions”, popularly elected by territory, roughly analogous to the US Senate. The Brown report was short on details, and Keir Starmer is reportedly reluctant to put drastic Lords reform on Labour’s short-term priority list.

Between retain and replace there has long been an array of possibilities. A comprehensive review by a joint Commons and Lords committee in 2002 came up with seven options, including wholly elected, wholly appointed and five hybrid schemes. They were put to a non-binding vote in both houses, which revealed a passion for indecision. The House of Commons voted against all seven options, while the House of Lords voted for the fully appointed option.

In the years since, some peers tell me, opinion within the House of Lords seems to have moved somewhat toward a hybrid, reflecting concern that their lack of a popular mandate makes it easier for the government and the Commons to take the Lords less seriously.

“I think our role as the revising and amending chamber used to be more widely accepted,” says William Richard Fletcher-Vane, 2nd Baron Inglewood, a barrister and unaffiliated member of the Lords. “Now there’s a feeling in both the government and the House of Commons that ‘We’re elected and we have a mandate to do exactly as we want, and you are a pesky nuisance’”.

Defenders of the appointed House point out that there’s nothing inherently sacrosanct about direct elections. Sometimes the mechanics of democracy are designed to balance conflicting interests or to avoid the tyranny of a majority. Prime ministers and cabinet members are not chosen by direct popular vote, and the UK judiciary certainly is not. (Nor is the president of the United States, who is anointed by the Electoral College, which has been described as “the exploding cigar of American politics”. Two of the four most recent US presidents won election despite losing the popular vote.)

“Putting it bluntly but accurately, a wholly elected second chamber would in practice mean that British public life was dominated even more than it is already by professional politicians,” said a royal commission set up by the Blair government and chaired by a conservative peer, Lord Wakeham. This would weaken the authority of the Commons and serve as a recipe for gridlock.

What do British voters want? Polling suggests the public is ambivalent, or possibly just confused. Back in 2006, a Populus poll presented voters with competing ideas.

What do British voters want? Polling suggests the public is ambivalent, or possibly just confused. Back in 2006, a Populus poll presented voters with competing ideas.

“The House of Lords should remain a mainly appointed house because this gives it a degree of independence from electoral politics and allows people with a broad range of experience and expertise to be involved in the law-making process”: 75 per cent of those polled agreed.

However, 72 per cent also agreed with the statement, “At least half of the members of the House of Lords should be elected so that the upper chamber of parliament has democratic legitimacy.”

More recently, a YouGov poll in August found 53 per cent of voters believe that the House of Lords should be “mostly” elected, which seems to me more an inclination than a demand.

At a time when liberal democracy feels imperilled around the globe, democratising the House of Lords might be cause for a little celebration well beyond Westminster. But if a new government chooses to take on reform, the trick will be to preserve the strengths of the Lords—the diversity of experience, the wariness of dogma, the ability to work across political boundaries, the devotion to the rule of law—so that it complements the unhappy tribe in the Commons without crippling it or—God forbid—replicating it.