Centrism used to be such a nice word. Cast your mind back to the 1990s, when Bill Clinton championed the “vital center” and Tony Blair’s Third Way was electorally unstoppable. In the afterglow of the Cold War’s end, humankind was going to find the golden mean between social justice and free-market capitalism, and all would be well. Or so, at any rate, it was claimed.

In the 2020s: not so much. True, Joe Biden, Emmanuel Macron and Keir Starmer are all centrists if they are anything, though only by default. In his party conference speech in Liverpool last year, the Labour leader explicitly declared that “on climate change, growth, aspiration, levelling-up, Brexit, economic responsibility we are the party of the centre-ground”. But neither he nor the US and French presidents can honestly be said to have redefined that political position with energy, inspiration or future-facing dynamism.

Today, the word “centrist” is more often a punchline than a badge of honour. On the right, an ugly populism holds sway, while the left’s vitality is mostly found in the new social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and environmentalist direct action groups.

This is the age of Brexit and Just Stop Oil, of social media polarisation and identity tribalism. The modern political taxonomy of “intersectionality”—of interconnected social categorisations such as race, sex and class—does not smile upon centrism. Indeed, the label “centrist dad” is only a notch or two up from “gammon” or “imperialist”. To identify as a centrist is to be seen as both wretchedly outdated and ideologically craven; analogue in a digital age.

If centrism is mentioned explicitly in mainstream discourse these days, the sense is generally pejorative or dismissive. As Danforth, the chief judge of the Salem witch trials in The Crucible, warns Francis Nurse: “there be no road between. This is a sharp time, now, a precise time—we live no longer in the dusky afternoon.” In “a sharp time” such as our own, well-intentioned moderacy and middle-way liberalism have become—for many—cause for profound ideological hostility, or derision, or both.

Here, for instance, is the essayist Rebecca Solnit writing in the Guardian in May 2021: “The idea that all bias is some deviation from an unbiased center is itself a bias that prevents pundits, journalists, politicians and plenty of others from recognizing some of the most ugly and impactful prejudices and assumptions of our times. I think of this bias, which insists the center is not biased, not afflicted with agendas, prejudices and destructive misperceptions, as status-quo bias.”

Ouch. Exasperation of this sort is not, of course, entirely new. In 1934, Trotsky wrote two ferocious attacks on the centrism that he witnessed lurking between revolutionary Marxism and “reformism”: an elusive hybrid position characterised by its “ideological emptiness”, its “parasitic existence” and “naive trust” in bourgeois democracy.

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail”, Martin Luther King famously declared that the Klansman was less of a stumbling block to Black civil rights than “the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice… Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.”

To identify as a centrist is to be seen as wretchedly outdated

Precisely because this was the high season of such centrism—the postwar era—King’s words were all the more stinging. Why was the “moderacy” that he attacked so prevalent? Two principal reasons. First, in the long shadow of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, there was an understandable appetite for political restraint; for calm, measured decency rather than ideological fervour and conflict.

Second, the Cold War had presented humanity with another deadly, Manichean struggle. In this case, it was between Soviet totalitarianism and western democracy; between two systems of economic organisation, communist and capitalist; between two superpowers engaged in a deadly nuclear arms race.

In an influential New York Times article in 1948, Arthur M Schlesinger—who would go on to be a close aide to President John F Kennedy—foresaw that neither “fascism nor communism can win so long as there remains a democratic middle way, which unites hopes of freedom and of economic abundance”.

In this country, the appeal of this very specific, postwar Atlanticist centrism meshed with a much older British affection for gradualism and evolutionary change; a cultural inclination encapsulated in the so-called “Whig interpretation of history”. According to this self-congratulatory version of our island story, Britain had resisted revolution over the centuries by the sage adaptation of its ancient institutions and the intermittent generosity of the ruling class.

In the second half of the 20th century, the key text for those who espoused such patrician moderacy was Harold Macmillan’s The Middle Way, first written in 1938 and reissued in 1966.

“We do not stand and have never stood for collectivism or the destruction of private rights”, wrote Macmillan of his class of conservativism. “We do not stand and have never stood for laissez-faire individualism or for putting the rights of the individual above his duty to his fellow men. We stand today, as we have always stood, to block the way to both these extremes and to all such extremes, and to point the path towards moderate and balanced views.”

In this respect, Supermac captured the essential ethos and temperament of all centrism. But he was also mapping out the terrain of the “postwar consensus”. This centre-ground was also called “Butskellism”, after Rab Butler, architect of the 1944 Education Act, and Hugh Gaitskell, Labour leader from 1955 to 1963. (Gaitskell wanted to rewrite the party constitution’s Clause IV—which committed Labour to a policy of common ownership of industry—almost 40 years before Blair finally scrapped it.)

The rise of Margaret Thatcher was both symptom and cause of the end of this consensus. Her intellectual guru, Keith Joseph, denounced the centre ground as “the lowest common denominator obtained from a calculus of assumed electoral expediency”, and repositioned the Tory stall on what he called the “common ground”: by which he meant the traditions, beliefs and sensibilities of the British people.

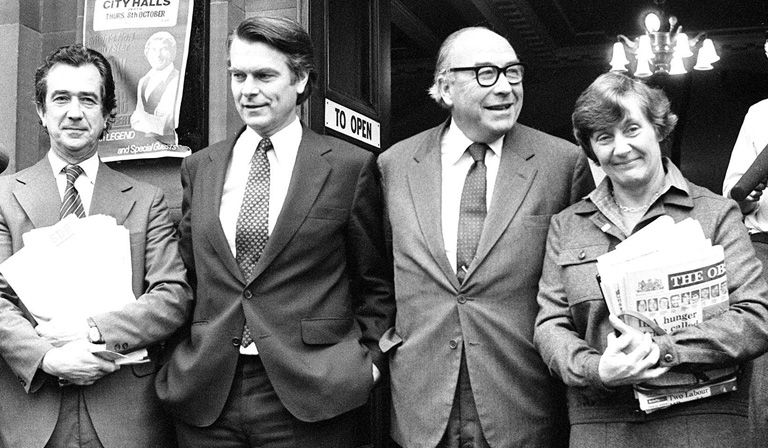

On the Labour side, meanwhile, the party’s leading centrists—Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen and Bill Rodgers—chose exile as the “Gang of Four” in 1981 and went on to found the Social Democratic Party, which merged with the Liberals in 1988.

Not until Blair’s victory in the Labour leadership contest of 1994 could one of the main parties again be accurately described as centrist. But New Labour’s 13 years in office defined British politics for more than two decades. The Conservatives did not return to government until 2010—in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, and only once they had embraced a measure of social modernity and declared their commitment to the NHS. David Cameron has described how he rode to the centre ground on a “husky-powered sled”.

Why excavate all this political history? To demonstrate how often centrism, in various guises, has held sway in British politics since the war, and how deep are its roots; but also to emphasise the abruptness of the breach when it was ditched and dismissed in the years before and after the 2016 Brexit referendum.

As Guardian journalist Rafael Behr notes in his fine book Politics: A Survivor’s Guide: “What it means to be a centrist has become inseparable from the Remain campaign in 2016 and the sense that it had misjudged the national mood, missed fundamental changes in the character of British politics”.

For those who seek a new role for centrism today, this is the diagnostic heart of the matter. It is seen as a loser’s creed, a set of muddled values that have been proven to fail. In this respect, the Global Financial Crisis between 2008 and 2009, well before Brexit, was a political earthquake whose tremors can still be felt today.

On the left, there was a broad sense of disgust that some financial institutions were apparently “too big to fail”, pointedly expressed by the hundreds of radical activists who camped out on Wall Street. On the right, populists such as Donald Trump and Nigel Farage portrayed the “liberal elite”, “globalists” and untrustworthy experts as treacherous conspirators who had sold out the great mass of patriotic Americans and Britons.

Centrism had defined itself primarily as an economic project, whose objective was to find a compromise between capitalism and social justice. It had little to say, in contrast, about nationhood, culture and belonging: its practitioners were caught napping by the surge of identity politics, on the left and right, in the 2010s.

The currency of centrism, furthermore, had always been data and evidence. It eschewed emotion and anything that smacked of sensationalism. As a consequence, it was totally ill-equipped for the seething world of the social media revolution, and the fissile new politics of hashtags, digital pile-ons and unprecedented impatience.

“Take Back Control” (the Leave campaign’s slogan) and “Make America Great Again” (Trump’s battle cry) addressed the sense that something had been lost on both sides of the Atlantic—or more accurately, betrayed. In this narrative, centrists were no longer the custodians of common sense. They were the gatekeepers of the institutions that had failed. They were a ruling class that was no longer trusted. They were the bad guys.

Before Boris Johnson was himself ousted, he purged the party of its One-Nation MPs, taking a blowtorch to one of the oldest Conservative traditions. I can recommend The Case for the Centre Right, edited by David Gauke, which includes intelligent essays by contributors such as Rory Stewart, Dominic Grieve and Amber Rudd. But it says a lot about the dire state of Tory populism that not one of the writers is a serving MP.

Is centrism finished, then? By no means. Indeed, it is the only electorally plausible alternative to the rampant populism that has been such an unmitigated disaster. To abandon the values that centrists have long held—the commitment to reason, practical public policy, the rule of law, internationalism, pluralism and basic decency—would be a grave abdication of responsibility.

Here is a non-exhaustive series of recommendations for its revival.

Accept that there is no pendulum: Most centrists have tended to believe that politics is governed by a pendulum swinging between two ideological poles, oscillating fairly predictably over the years. If this was ever true, it certainly isn’t now. Contemporary politics owes more to the uncertainties of quantum theory than to predictable Newtonian physics. If you doubt this, consider the astonishing phenomenon of Trump’s enduring popularity, as each indictment appears to strengthen his appeal.

Wipe the slate clean: Yes, it is strategically logical for centrists to hope that the UK may one day rejoin the EU. But under no circumstances can centrism be perceived as a restorationist project, seeking only to relitigate the 2016 campaign or reboot Blairism. Instead, it must address itself remorselessly to the challenges of today: inequality (between generations, regions, people and nations), the climate emergency, pandemic prevention, technological change, international security. It must be bracingly contemporary, not nostalgic. The old 20th-century argument between the state and the market, between the collective and the individual, is no longer the only question, or even the main one.

Be internationalist, but patriotic: In an interdependent world, centrism must be internationalist in approach, and fearless in this regard. But—mindful of Jeremy Corbyn’s 2019 election disaster—it must also embrace patriotism, offer a generous version of Britishness and distinguish it from nationalism (to be fair, Starmer clearly gets this, as he showed by opening the 2022 Labour party conference with the national anthem).

Any centrist who does not support a wealth tax is kidding themselves

Learn from identity politics: The social justice movements have, as many liberals object, become too preoccupied with the restriction of speech and digital scolding. But their reproach to liberalism, universalism and meritocracy should be heeded. Liberal democracy has not been even-handed in its rewards or delivered the goods in the fight against racism and misogyny. The centrists of the 21st century must acknowledge this and forge a new progressivism that is as conscious of identity as it is of the claims of the individual. This is a moral, as well as a generational, necessity.

Clean up Westminster: The Conservatives’ deranged response to the ethical crash that brought down Johnson was to have an extended public argument about tax cuts. It is 28 years since Lord Nolan’s first report on standards in public life was presented to the prime minister—and the case for a fresh round of root-and-branch reform could scarcely be clearer. Parliament’s Independent Complaints and Grievance Scheme—launched in 2018 in response to the #MeToo uprising—lacks the resources and sanctions it needs to make a true impact. Absurdly, the independent adviser on ministers’ interests (Laurie Magnus) cannot initiate his own investigations but must wait to be so instructed by the prime minister. In June, the Conservative chair of the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, Eric Pickles, complained that the days “when ‘good chaps’ could be relied on to observe the letter and the spirit of the Rules” governing job offers to former ministers were well and truly over. Between now and polling day, Starmer will be urged to promise all manner of constitutional reforms, including a new electoral system. But, if elected, he should make his priority the rebuilding of trust in our core political institutions: the task is urgent.

Surprise the voters with honesty: Johnson’s boosterism—his promise of “world-beating” everything—ran aground quickly and only strengthened the conviction that all politicians are liars. His critics saw his bombast as further evidence that public life had become unmoored from reality in our post-truth age. Yet history suggests that voters respond to leaders who have the honesty to admit the difficulty of an undertaking and to promise “blood, toil, tears and sweat”. The problems of the coming decades are going to require more and smarter government. Yes, the books have to balance. But these projects will inescapably involve more investment—some of it from the public purse. So, for instance, any centrist who does not support and argue for a wealth tax is kidding themselves. After endless empty rhetoric about “small boats” and Rwanda, dare to acknowledge the complexity of border control in the modern world. Level with the electorate. Make candour your friend.

Champion radical practicality: Radicalism is too important to be left to extremists. The characteristic pitfall of centrism is caution and timidity, a huddle around an equidistant point between left and right (remember Change UK, the short-lived centrist party formed in 2019 by Chuka Umunna, Anna Soubry, Heidi Allen and a handful of other disillusioned Labour and Conservative MPs? I thought not). These are not timid times, and centrists in the 2020s must be unashamedly ambitious. Telling someone who cannot feed their children to calm down and be sensible is a fool’s errand.

Understand that feelings don’t care about your facts: Centrists are addicted to evidence, and rightly so. Sound public policy is rooted in fact, science and empirical investigation. But old-school technocracy is nowhere near sufficient in today’s weaponised digital landscape, which—like it or not—is governed by emotion. Those who believe in rational centrism must also learn the skills of narrative and the techniques of storytelling that shape political discourse today. In the phrase coined by the American sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild, contemporary voters expect politicians to respect the “deep story” that underpins their political attitudes: “It’s the story feelings tell, in the language of symbols. It removes judgment. It removes fact. It tells us how things feel.” Centrism must rediscover the full toolkit of visionary leadership and popular persuasion—synthesising fact and feeling. As Rory Stewart writes in the Gauke volume, “The ability to inspire a crowd should not be confined to demagogues. A sense of humour need not be a monopoly of charlatans.”

Don’t be wimpish: It may be unfair of voters to see centrists as wusses, but politics has never been fair. The caricature is rooted in a perceived lack of commitment (hedging your bets), an absence of conviction (bloodless technocracy) and effete circumspection (when electoral caution becomes political stasis). This has nothing to do with machismo, by the way. The very model of passionate centrism is Caroline Lucas, the outgoing Green MP for Brighton Pavilion (witness her remarks in the debate on Johnson’s lies to parliament on 19th June, in which she denounced the Tory absentees and the abstainers, which included Rishi Sunak, as “guilty not just of cowardice, but complicity”). Starmer’s defenders say that his bouts of political reticence reflect a belief in the maxim attributed to Napoleon: never interfere with the enemy when he is in the process of destroying himself. Given the Tories’ present genius for catastrophe, this approach has some merit—insofar as it goes. But it is nowhere near sufficient for a leader who, if he wins, will inherit perhaps the most challenging political landscape to face an incoming PM since Thatcher. He cannot afford to be seen as (much less be) battle-shy. No governing strategy for the 2020s is worthy of the name unless it involves a hefty measure of risk and a readiness for political combat. Put up your dukes, Sir Keir.

The next year will be a defining one for liberal democracy in this country and the US. As things stand, Biden will be facing a re-match with Trump on 5th November 2024, while Sunak is likely to go to the country in the spring or the autumn.

Against such a backdrop, centrists have a duty to stop apologising, to face the future and to embrace the formidable task ahead. “In a dark time, the eye begins to see,” wrote the poet Theodore Roethke. It is indeed time for the decent, the rational and the committed to demonstrate precisely this clarity of vision.