In the pantheon of disastrous postwar chancellors the unlamented Kwasi Kwarteng will inevitably enjoy pride of place. There is, however, another who occupied that illustrious office for rather longer and who, if there is any justice in this world, ought to be a contender for the same honour. I refer, of course, to Mr George Osborne.

Long after his departure for sunnier climes in the City of London and elsewhere, the bills for his management of the economy are still coming in—as they will continue to for many years to come. The present crises in health, education and care of the elderly, the decline of most non-statutory local services, stalling life expectancy, and a rise in recorded violent crime all have their roots in his disastrous—and ultimately unsuccessful—attempt to pay down the deficit. In his recent appearance at the Covid inquiry, Osborne was asked whether, as a result of austerity, the UK entered the pandemic with depleted public services. Naturally, he denied all. It remains to be seen what the inquiry will conclude.

With an election year approaching, we can no doubt expect to hear more from the current management and their friends about how Labour “crashed” the economy last time round, so it is worth recalling what actually happened.

It is easy to forget that when Tony Blair’s government invested heavily in health, education and local government these were electorally popular choices. Realising this, the Tories under David Cameron and Osborne promised to match “pound for pound” Labour spending on the main public services. They promised tax cuts, too, to be funded by our old friend, the proceeds of growth.

Osborne, like Gordon Brown, was a great advocate of deregulating the financial sector—a process that began with Thatcher’s “Big Bang” in 1986, which brought to London all sorts of US financial houses, with their dodgy practices and culture of greed. Arguably, this is what led to the financial meltdown of 2007–2008.

None of this, however, was apparent in the early years. Brown’s biggest mistake, in an otherwise impressive decade as chancellor, was to buy into the City’s own estimation of itself. His speeches to the Lord Mayor and assembled bankers at Mansion House each year became more and more euphoric. This, for example, is what he told assembled City slickers soon after he became chancellor in 1997: “[The City] has demonstrated the best qualities of our country, what I describe as the British genius.” In 2004, he said: “I want us to do even more to encourage the risk-takers.” And in June 2007, just before the chickens came home to roost, he heralded Britain as “a new world leader” thanks to the “efforts, ingenuity and creativity” of those present. “Britain needs more of the vigour, ingenuity and aspiration that you already demonstrate”. He went on to speak of “an era that history will record as the beginning of a new golden age for the City”.

By the time the crisis was over, every one of the demutualised building societies had disappeared

One forgets what it was like to live in an era—pre-crash, pre-pandemic—when the public finances were in good order. Public debt was low by historic standards. Boom and bust had allegedly been banished. Despite the occasional wobble, the markets were soaring. There was even talk of tax cuts. It was not easy to be a Tory shadow chancellor at a time of such apparently unparalleled prosperity.

Osborne, however, rose magnificently to the occasion. There are many entitled to criticise Brown for his addiction to deregulation, but Osborne is not one of them. No cut in taxes, no amount of slashing red tape, was ever enough. At every announcement by chancellor Brown, Osborne was on his feet demanding more. This, for example, was Osborne on the offensive in November 2006: “In an age of greater choice, he [Brown] offers more overbearing control… in an age that demands a light touch, he offers that clunking fist.” One year on, the clunking fist would prove to be exactly what was needed if catastrophe were to be avoided—and no one, least of all Osborne, was in a position to object.

The reckoning began in mid-2007, with the first signs of collapse in the US sub-prime mortgage market. In Europe the impact was felt first in Germany; then, suddenly, on 9th August, BNP Paribas—the largest bank in France—looked close to the edge. In the UK, calm temporarily prevailed. The chancellor, Alistair Darling, was on holiday, but it was not to be long before the contagion reached our shores.

First to implode was Northern Rock, the Newcastle-based building society that, in keeping with the spirit of the age, had turned itself into a bank, thrown caution to the wind and was lending to customers at many times their annual income, subject to minimal background checks. Its impending meltdown threatened the savings of many on modest incomes and led to queues of depositors trying to withdraw their money—a sight not seen in the UK in living memory. Within weeks, the government had stepped in, initially guaranteeing all deposits (later reduced to £50,000) and saving the bank from collapse. Full nationalisation would follow in February 2008, and it was eventually taken over by Richard Branson’s Virgin Money.

In due course other former building societies—which, in the heady days when deregulation was all the rage, had also become banks—would follow Northern Rock into the abyss. By the time the crisis was over, every one of the demutualised building societies had disappeared. The only survivors were those whose management and members had resisted the temptation of fool’s gold.

Although the crisis began in the US mortgage market, it rapidly spread across the developed world. The UK was particularly vulnerable, having been in the vanguard of US-style deregulation. The bailout of the two biggest US mortgage lenders and, in September 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers, one of the biggest investment banks in the US, sent shockwaves around the world.

British bankers, however, remained in denial until the last minute. In his gripping account of the crisis, Darling describes a phone call on 11th October 2008 from Tom McKillop, chairman of the Royal Bank of Scotland: “He told me his bank would collapse within hours. What was I going to do about it?”

Two days later, the government announced that it was effectively nationalising (“recapitalising” was the word of the hour) three of the country’s biggest banks. “Congratulations,” I remarked to Darling in the House of Commons tea room shortly after he had made the momentous announcement, “you have just implemented the 1983 Labour election manifesto.” “Yes,” he replied, “and with the backing of the Tories.”

Where Britain led, others followed. True, the Americans also had a plan, but they were in the final weeks of a presidential election and their political system was paralysed. It wasn’t until Britain moved that the US got its act together. Internationally, if not at home, Brown’s prestige was high—so much so that the French president invited him to address eurozone leaders, even though the UK was not part of the eurozone. The G20 would also swing in behind Brown’s leadership, agreeing an enormous and coordinated stimulus package and boosting IMF currency reserves, which countries could draw down while the credit markets were frozen.

Amid all this, Osborne, in the face of Armageddon, had abandoned his love of free markets and deregulation and backed nationalisation of the banks. A seminal hour in British politics, or at least it ought to have been. It did not take long for the air of humility—contrition would be putting it too strongly—that had briefly descended on the party of bankers, hedge funders, derivative traders and assorted City alchemists to evaporate. While Brown and other leaders were preoccupied with addressing the crisis, Osborne and Cameron spotted a window of opportunity.

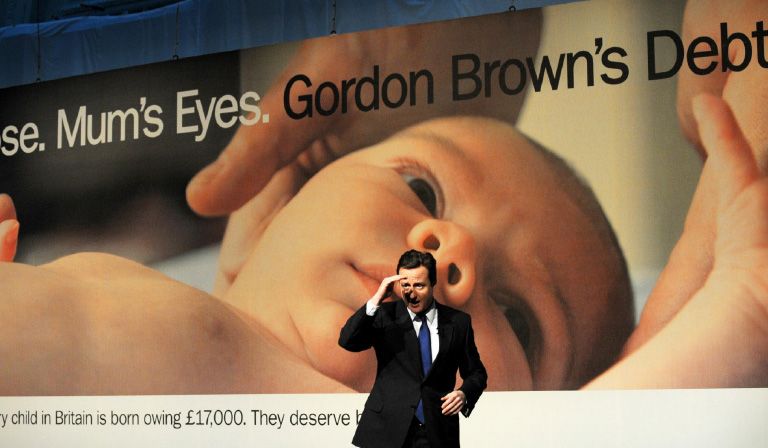

One morning in November 2008, they got up and decided that their previous undertakings to match Labour’s spending on public services were now, in the memorable word of the Nixon White House, “inoperable”. From this moment onwards, the line would be that the pain caused by the financial crisis, insofar as it applied to the UK, was all or mainly the result of the Labour government’s profligacy. To meet the needs of the hour, they had devised a number of cynical—but brilliantly effective—slogans, which in the years ahead were destined to become common parlance. “The mess that Labour left” was a favourite, along with the accusation that Brown had failed to “fix the roof while the sun was shining”. One campaign poster featured a picture of a baby alongside the words: “Dad’s nose. Mum’s eyes. Gordon Brown’s debt.” Before long, attack lines like these were being parroted by Conservative MPs and candidates the length and breadth of the land. Comparisons were made, apparently in all seriousness, with Zimbabwe.

When challenged—and they were not often challenged—Osborne might briefly concede that the crisis may have had something to do with the near-collapse of the US financial sector and that it afflicted other major economies besides ours. But he swiftly reverted to safer ground, and came under remarkably little pressure to do otherwise.

Quietly, very quietly, you could hear reality acknowledged in the most unlikely places. One evening in October 2009, the chairman of the Treasury Select Committee, John McFall, recounted to me that he had just returned from a seminar in the City at which the chair of the event—a banker—had gone out of his way to express gratitude to the Labour government for its intervention, without which (he said) the entire banking system would have gone down. Such sentiments, however, were rarely spoken aloud. The prevailing narrative, that Labour had crashed the economy, went more or less unchallenged.

In November 2009, I found myself invited to the annual dinner of the Institute of Directors. It was hardly my natural habitat, but I went along out of curiosity. It was a lavish event: 700 black-tie business folk, four courses, good wines. The entertainment was by Ronnie Corbett and former chancellor Ken Clarke. There was not much evidence of recession, despite several references from the platform to “hard times”, accompanied by the usual demands for lower taxes, less government interference and so on (except, presumably, when it came to rescuing the banks).

Clarke, entertaining as ever, complained for 20 minutes about the government’s allegedly catastrophic levels of debt without once conceding that it was almost entirely down to the cost of rescuing the economy from the consequences of the greed and avarice of his party’s friends in the City. At one point, only slightly tongue-in-cheek, he too compared the government’s fiscal policy to that of Robert Mugabe. But, even in this most Tory of settings, not everyone was signed up to the mantras coming from the platform. At the mention of shadow chancellor Osborne, someone at my table whispered: “If that guy had been in charge last autumn, there would have been meltdown.”

In autumn 2009, BBC Two aired The Love of Money, a three-part documentary on the crisis that included interviews with a wide range of political leaders, bankers and regulators at home and abroad who had been involved in resolving it. Many, including the former head of the US Federal Reserve and several prime ministers, paid tribute to the role that Brown had played in preventing a crash of the global economy. I thought to myself at the time: “How come foreigners know about this, but it appears to be a secret at home?”

Part of the answer, of course, lay with our free press. It simply did not suit most newspapers to air such sentiments in the run-up to an election. But the charade continued well beyond polling day. For years afterwards, Osborne, Cameron and their supporters continued to chant the slogans that had become ingrained in the British psyche. “The mess that we inherited” would remain an alibi for the damage chancellor Osborne inflicted on the social fabric. Even today, a decade after the event, one can occasionally hear such sentiments trotted out by Tory MPs under pressure.

It was not helped, of course, by the foolish note that Labour Treasury minister Liam Byrne left behind for his successor David Laws: “Dear chief secretary, I’m afraid there is no money. Kind regards—and good luck! Liam.” It was meant as a joke, of course, but for years afterwards it was ruthlessly exploited by the Tories—and who can blame them? Conservative HQ issued a facsimile (which can still be found online) and it become a weapon in every Tory candidate’s arsenal.

Nor was Labour helped by the fact that its new leader, Ed Miliband, seemed reluctant to challenge the falsehoods put about by his opponents. Admittedly, the lie would not have been easy to counter, given how entrenched it had become—but he might have tried harder. As for the Liberal Democrats, who much to their surprise found themselves in coalition with the Tories, they fell enthusiastically into line with their new friends. Danny Alexander, the Lib Dem who became the long-serving chief secretary to the Treasury after Laws had to step down, almost immediately went native. Their leader, the ever-flexible Nick Clegg, went about demanding “savage and bold cuts”.

It was only when the memoirs came out that a different picture emerged. In his 2015 account of the crisis and its fallout, After the Storm, Vince Cable, a leading member of the coalition government who also had the distinction of being the only senior politician to warn in advance of where the reckless behaviour of the banks and building societies was leading, wrote: “It is not true that the Labour government grossly mismanaged the public finances in the run-up to the 2008 crisis. There was small structural deficit, but the Conservative narrative of spendthrift incompetents is simply wrong.”

And this was Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman writing in the New York Times in June 2015: “One important factor in the recent Conservative election triumph was the way Britain’s news media told voters, again and again, that excessive government spending under Labour caused the financial crisis. It takes almost no homework to show that this claim is absurd on multiple levels. For one thing, the financial crisis was global; did Gordon Brown’s alleged overspending cause the housing busts in Florida and Spain? For another, all these claims of irresponsibility involve rewriting history, because on the eve of crisis nobody thought Britain was being profligate: debt was low by historical standards and the deficit fairly small. Finally, Britain’s supposedly disastrous fiscal position has never worried the markets, which have remained happy to buy British bonds… Nonetheless, that’s the story, generally repeated not as opinion but as fact. And the really bad news is that Britain’s leaders seem to believe their own propaganda.”

The chief propagandist was Osborne and, in 2010, having spent months insisting that the country was on the verge of ruin, he now had an excuse to do what he had instinctively wanted to do all along—lay waste to much of the public sector. No one disputed that there would have to be cuts in public spending, given the vast sums required to rescue the financial sector from the consequences of its own folly, but it is hard to justify what came next. Recklessly, on becoming chancellor, Osborne pledged to eliminate the deficit on the day-to-day budget by 2013 to 2014. He never managed to deliver this—when he left office in 2016 it was still a distant prospect—but immense damage had been done in the process.

In order to achieve his aim, he pledged from the outset to impose a tightening of roughly £113bn, more than 75 per cent of which would be found by slashing overall public spending. He was also determined that the burden would fall overwhelmingly on the public sector. What followed was the decade of austerity. No area of public service was untouched. Many public sector workers were subjected to a decade-long wage squeeze, or indeed a substantial fall—especially where work was outsourced to the private sector.

Local government was especially hard hit—libraries, youth clubs, refuse collection, child protection and social care all suffered. According to a National Audit Office report, central government’s contribution to local authority budgets was cut by 49 per cent between 2010–11 and 2017–18. A statement from the Tory-controlled Local Government Association said: “We have repeatedly warned of the serious consequences of funding pressures facing local services from unprecedented funding reductions since 2010 and growing demand for services.” The warnings, it seems, went unheeded.

Among the casualties was the Labour government’s Sure Start programme, which aimed at improving the life chances of young children, often in the most deprived areas. By February 2020, about one third of the 3,600 children’s centres set up under the Sure Start programme had closed, and most of the others were a shadow of their former selves.

Almost wherever you looked—from drug problems to the number of homeless families in bed and breakfast accommodation—all the indices of social welfare were in sharp decline. Nowhere was this more pronounced than in the prisons. Ken Clarke, by then justice secretary, was the first cabinet minister to sign up to the cuts, boasting as he did so that, as a former chancellor, he understood the need for drastic reductions in public spending. These would trigger years of crises with which the prison, police and criminal justice systems grapple to this day. Prison education, the best hope of preventing reoffending, was devastated. The budgets of important government bodies such as the Environment Agency were slashed, with the result that they are no longer able to function effectively. It took some time for the impact to show through—but it is now apparent in, for example, the relative impunity with which the water companies are able to pour sewage into rivers and the sea.

Step by ruthless step, just about all the social gains of the previous decade were eroded. The only exception was the national minimum wage, strongly opposed by the Tories in opposition but eagerly embraced by Osborne as chancellor. In many areas, however, it became a maximum, not a minimum.

If you are a student of the dark arts of politics, the dexterity with which Cameron and Osborne managed to convince a fair swathe of public opinion that the economic pain of 2008 onwards was caused by the profligacy of the -Labour government will be cause for admiration—awe, even. If, however, you were on the receiving end, your view will be different. Surveying the wreckage, that most perceptive social democrat politician, the late Shirley Williams, summed up Osborne’s achievement by saying that he had turned what was by any measure a crisis of capitalism into a crisis of the public sector.

For all that Osborne went on about his dismal “inheritance”, what he in fact inherited was a healthy growth rate. The economy would expand by around 2.5 per cent in 2010, which was not exceeded for another four years—and then only briefly. What Osborne appears to have overlooked in his vendetta against the public sector was the impact his programme of cuts would have on overall levels of economic growth, with the result that, on his watch, public debt as a percentage of GDP actually increased. Between 2010 and 2011, he inherited a ratio of debt to GDP of roughly 70 per cent. By the time he left office in 2016, despite half a decade of austerity, it was substantially over 80 per cent. In 2013, the UK lost its triple-A credit rating for the first time since 1978—something which it managed to hang on to throughout the crisis of 2007 and 2008, despite shadow chancellor Osborne’s predictions of impending bankruptcy.

Osborne’s austerity programme had other consequences, too. The long freeze on public service wages led to a growing sense of resentment. That resentment was exacerbated by the perception that those whose irresponsibility had caused the meltdown got clean away. Before long, the bankers seemed to be back to business as usual, paying themselves huge bonuses and demanding lower taxes. “There was a period of remorse and apology for banks and I think that needs to be over,” Barclays boss Bob Diamond told the Treasury Select Committee in January 2011. It was certainly over for him. He was awarded a bonus of £6.5m while most of the country was still furious at the way the burden had fallen—and would be for many years. Witness the growing anger among teachers, nurses and other public servants which, prompted by rising inflation, came to a head in the winter of 2022 and early 2023.

In his vendetta against the public sector, Osborne overlooked the impact his cuts would have on growth

Was there another way? Did the burden have to fall so heavily on the public sector? Did the cuts have to be quite so drastic—and implemented with such evident glee? Who now remembers Osborne’s notorious 2012 party conference speech, which painted a picture of “strivers versus skivers” to justify benefit cuts? Addressing the conference hall, he asked: “Where is the fairness… for the shift-worker leaving home in the dark hours of the early morning, who looks up at the closed blinds of their next-door neighbour, sleeping off a life on benefits?” Listening to Osborne these days, calmly and apparently rationally justifying his handling of the economy, it is easy to forget just how low he sunk.

Despite his repeated attempts to spook the markets in the final period of the Labour government, the markets appeared to be remarkably calm, seemingly satisfied with the measures being taken by Brown and Darling. Then—and for years to come—interest rates remained at record lows. The government could fund the deficit more cheaply and easily than at any time in living memory. Might it have been possible that, instead of making irresponsible—and, as it turned out, undeliverable—promises to pay down the deficit in just four years, Osborne could have refinanced the debt over a much longer period, without the slightest adverse reaction from the markets?

There were economists who understood the true position. Robert Skidelsky was one, and he was by no means alone. “A true Keynesian,” he wrote in 2014, “would have said that what was needed… was fiscal expansion, not consolidation.” “Osborne’s cuts,” he said in 2018, “chopped down the ‘green shoots of recovery’ that had begun to appear at the end of 2009, and condemned Britain to at least two further years of stagnation.” He also argued that when the government resorted to quantitative easing—in effect the printing of money—in a desperate attempt to stimulate the economy, the benefits went largely to the already prosperous, who tended to save rather than spend, and whose growing prosperity did not, therefore, stimulate the economy as spending by poorer people might have done.

A friend who worked in Downing Street recalled that he was once sitting in on a discussion about proposed cuts to tax credits, during the course of which Osborne casually remarked that he didn’t know anybody who earned less than £100,000 a year. These days, of course, he mixes in even more rarefied circles. Who knows what the current figure would be?

No sooner was Osborne out of office in 2016 than he entered the warm embrace of those who had done so much to bring the economy to the brink of ruin. Less than a year after his dismissal as chancellor he was reported to have earned £800,000 from speeches, including in Wall Street and the City. Just two, at events organised by JP Morgan, earned him more than £140,000. While still an MP, he took a job as an adviser to BlackRock, the world’s biggest fund manager, at a salary of £650,000 for one day’s work a week. Later, he became editor of the Evening Standard, in which capacity he sought to avenge himself on Theresa May, whose first decision on becoming prime minister had been to sack him.

Osborne has rarely had to answer for his sins, but in October 2017, in a long and thoughtful interview with Andrew Neil at an event organised by the Spectator, he was asked whether Brown and the Labour government were really responsible for the crash.

He replied: “Did Gordon Brown cause the sub-prime crisis in America? No. And although I would have questions about some of the decisions taken in 2007 and 2008, broadly speaking the government did what was necessary in a very difficult situation.” Now he tells us.