In years to come we shall be able to tell whether the 2010-15 parliament was an aberration or the new normal. For decades, key elements of the story remained much the same. A new government would enjoy a brief honeymoon, then succumb to deep mid-term blues while the main opposition and/or the Liberals (under their various names) made spectacular local and by-election gains. Then as the next general election hove into view, the government would recover. Normally the only significant question was whether it would recover enough to remain in office.

The story this time has been different. With the Liberal Democrats in coalition, they were never likely to enjoy a mid-term boost. As the sole major opposition party, Labour should have benefited from the government’s misfortunes. Instead we have seen the growth in support for the UK Independence Party, the Scottish National Party and, for a while, the Greens. But have we seen a fundamental change in the character of party contest in Britain, or will the old rhythms of the parliamentary cycle reassert themselves?

Let’s sift the clues, starting with the shifting party fortunes of the past five years. The initial honeymoon helped only one coalition party. The Conservatives built on their 37 per cent support on polling day to sustain a steady 40-42 per cent between June and December 2010. In contrast, Lib Dem support dropped swiftly from 24 per cent to 9 per cent at the end of the year.

At first, Labour was the clear beneficiary of the Lib Dems’ decline. Its support rose to 41 per cent by December, 11 points up on the general election. As we entered 2011, Britain seemed to be returning to two-party politics, with Labour and Conservative both above 40 per cent for the first time for almost 20 years.

It didn’t last. As living standards and the economy stalled, Tory support slipped, allowing Labour to move into a 5-7 point lead in the summer of 2011. We looked to be heading towards a conventional mid-term, with Labour the beneficiaries of government unpopularity. However, the Tories staged a fight back, drawing level in January 2012—but then came the “omnishambles” budget, which pushed them back down to 32-33 per cent. For the next 12 months, Labour stayed around 10 points ahead, although historically, this was pretty modest.

The narrative darted off in a wholly new direction in 2013. Ukip’s support, which had been creeping up, started to achieve real momentum in the 2013 local elections, when they won 20 per cent support. They played the role so often acted out by the Lib Dems in the past, winning over voters in local and by-elections.

Although Ukip dented Labour’s vote in some northern cities, their gains hurt the Tories far more. Ukip’s support trebled between January 2012 and May 2013, from 5 to 15 per cent. Labour’s share fell just one point in that time, while the Conservatives lost 10 points. David Cameron was paying the price for the economy appearing to flatline and the deficit remaining far higher than he and George Osborne had promised.

May 2013 was the Tories’ low point. From July that year until parliament was dissolved a few weeks ago, the Tories’ monthly poll average remained on 33 per cent plus or minus one point. However, starting around a year ago, that percentage began to look increasingly healthy, as Labour slipped back, from 39 per cent in early 2014 to 33-34 per cent early this year. Both Ukip and the Greens were picking up votes at Labour’s expense in England, while the SNP crushed Labour’s hopes in Scotland.

Thus Britain ended the 2015 election campaign with the two main parties level-pegging, not because the Tories were recovering, but because of the way the non-Conservative vote had rearranged itself.

What about the attitudes that have prompted those shifting fortunes?

Party leaders

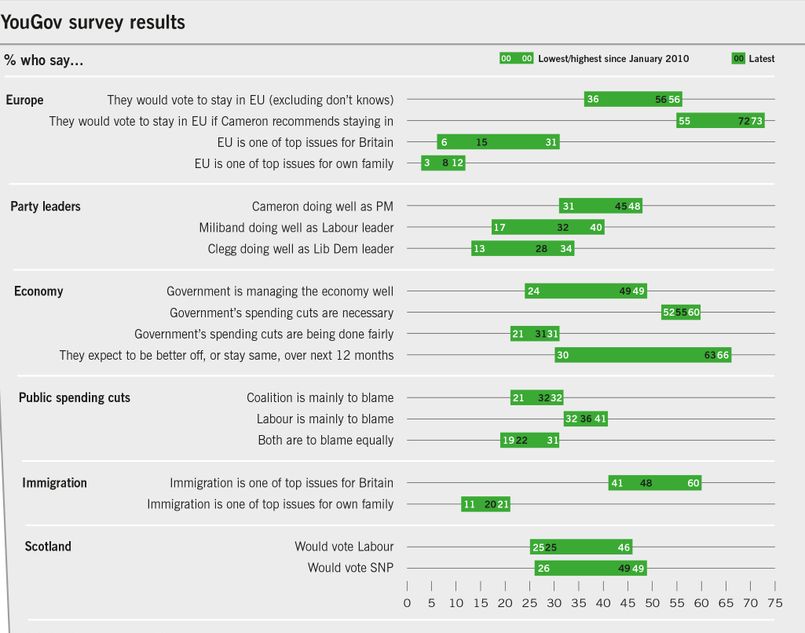

Only once during the parliament has Miliband enjoyed a higher rating than Cameron. At Labour’s conference in 2012, Miliband adopted Benjamin Disraeli’s “one nation” mantra in a speech delivered without notes. Voters loved it. In a single week, the proportion saying he was doing well jumped from 28 to 40 per cent, overtaking Cameron’s score of 35 per cent.However, it proved a one-week wonder. Miliband’s ratings swiftly slipped back. The same thing happened in July 2011 when he attacked Rupert Murdoch over phone-hacking, and September 2013 when he promised to curb gas and electricity prices. Otherwise, Miliband has consistently scored less well than his party, while Cameron has outperformed the Conservatives.

The Labour leader’s big problem is that only around one in five voters think he is up to the job of Prime Minister. He scores well for being “in touch with ordinary people,” but has consistently been well behind Cameron for being “strong,” “decisive” and “good in a crisis.”

Miliband’s one consolation has been that for much of the parliament, Nick Clegg fared even worse. In the first weeks of the coalition, he vied with Cameron for popularity, with around 60 per cent saying both men were doing well. But the Lib Dem U-turn on tuition fees cost him dear. By November 2010, Cameron still enjoyed an approval rating of 50 per cent while Clegg’s was down to 32 per cent.

Had Clegg held the line there, he could have been reasonably happy. But he didn’t. Last June, in the wake of the European parliament elections when the Lib Dems came fifth in the popular vote and lost all bar one of its seats in the parliament, his rating was down to just 13 per cent.

All three party leaders saw their popularity pick up this spring, as the general election approached. But by now the pattern was well-established, with Cameron out in front, well ahead of Miliband who, in turn, was outperforming Clegg.

Party images

If the Prime Minister could be pleased with his personal scores, those of his party were another matter. In some ways, the Tory brand remains toxic. After 10 years of his leadership, Cameron has yet to persuade people that his party is on the side of ordinary voters. Instead it is still regarded by most as a party of the rich, “out of touch with the way ordinary people live their lives.” The proportion thinking this has barely changed in two years.But the Labour and the Lib Dem brands also have weaknesses, and have not been able to shed negative perceptions: Labour being “out of its depth,” and the Lib Dems having “sold out their principles by going into coalition with the Conservatives.”

"In some ways it is odd that the economy is the Conservatives’ strongest card"Never before have all three parties had such big problems at the same time. This helps to explain the popularity of the insurgent parties—Ukip, the SNP and, to a lesser extent, the Greens.

However, the more notice Ukip attracts, the more it repels many voters. Unlike the other parties, its image has deteriorated as the election has approached. The proportion saying it is “full of oddballs and extremists” has climbed in recent months from 43 to 57 per cent. Much of the rise has taken place among people who would never vote for it anyway; but if Ukip is to break into the big time in the next five or 10 years, it will have to address its reputation for being a party of fruitcakes.

The economy

In some ways it is odd that the economy is the Conservatives’ strongest card. Living standards are about the same as five years ago, with Ed Balls and George Osborne bickering over whether they are fractionally up or fractionally down since 2010. Either way, the record is not great. In any normal five-year period they would be up 10 to 15 per cent. However, Labour has been unable to shed its reputation for driving the economy into the ditch before the last election. Most people think the public spending cuts are necessary—and throughout the past five years, Labour has been blamed more than the Tories.What is more, as growth has gathered pace and unemployment fallen, YouGov’s indicators have moved the Conservatives’ way. Compared with the middle period of the parliament, when most voters feared austerity would never end, optimism is up, as is approval of the coalition’s record of economic management. Although only a minority think public spending cuts have been done fairly, that minority has steadily grown in recent months.

Explore the data:

Europe

Support for British membership of the European Union has grown as the general election approaches. For much of 2012 most Britons wanted the UK to withdraw. Cameron’s speech in January 2013, when he laid out his plans for renegotiation, helped to turn the tide. Now, by a clear if modest margin, most people who take sides would vote to stay in. The majority rises to well over two-to-one when people are asked how they would vote if Cameron returned from renegotiations saying he had protected Britain’s interests and recommended staying in the EU.Not that Europe currently figures high in voters’ concerns. Only 15 per cent say it is one of the top issues facing Britain—and only 8 per cent when people are asked to pick up to three issues of special concern to their family. Even among Ukip voters, that figure rises to only 20 per cent. What worries them much more is...

Immigration

This is a classic “symbolic” issue which voters believe says something larger about Britain today. Throughout the 2010-15 parliament, voters have considered immigration to be one of the big problems facing the UK; but when they are asked to say which issues matter most to them and their family, immigration comes lower on the list than the economy, NHS, pensions and taxation.Only among Ukip supporters is immigration the top concern. That said, there is no doubt that, by consistently large majorities, voters want net immigration into Britain cut sharply. But this demand is linked to a widespread belief that immigrants come to Britain in huge numbers to live on benefits rather than get a job—a perception at odds with official data, as last month’s YouGov/Prospect survey showed.

Scotland

In the long run, how Scotland votes could matter more to the future of the UK than anything else. September’s referendum produced a clear 55-45 per cent majority for remaining in the UK—yet since then, every poll has pointed to an equally clear SNP victory in the general election. How come?The referendum polarised party loyalties, just as it polarised the country on independence. Previous elections had fitted the pattern of Scots being far more willing to vote SNP for the Scottish parliament than for Westminster. Following the referendum, that has changed. Scots are less willing to split their vote. The SNP has persuaded many of them to stay with the party for next month’s election.

In the past, the term “the 45” referred to Bonnie Prince Charlie’s failed uprising in 1745. Now, it is used to refer to the percentage supporting the SNP in 2011, voting for independence in 2014 and telling pollsters they will vote SNP on 7th May. They are mostly the same people. But whereas 45 per cent is a losing share in a referendum, it can provide a landslide in a first-past-the-post election. It looks as if on the night of 7th May, British politics will be shaken by SNP victories in seat after seat—even though the total vote for the unionist parties will exceed SNP support in many of those contests.

There is the prospect that we shall be able to divide the minority parties into two clusters, each scoring four to five million votes: the SNP, Lib Dems and Democratic Unionists, with around 80 seats combined—and Ukip and the Greens with maybe no more than five MPs. Britain’s voting system may not be at the top of the list of politicians’ concerns as they grapple with the outcome of this year’s election; but, as with Scotland’s future status, it may well be a matter that returns to the top of the political agenda sooner rather than later.