Once upon a time, Worthing was the sort of gently ageing seaside town unkindly known as “God’s waiting room.”

So when Beccy Cooper and her husband were househunting along the south coast, they didn’t initially see it as a place to raise two young sons. But two years on, the public health consultant is delighted that they took the plunge and moved in: “There’s so much going on. A lot of the families we know have come from Brighton because you can get more for your money here, and when you get that influx of people, you get changes—lots of interesting cafés, different arts and culture, independent shops and lots of entrepreneurial businesses opening up. It’s a great place to live, incredibly dynamic.”

And it’s changing in more ways than one. This summer, Cooper became Worthing’s first Labour councillor in 40 years. Her party now has serious designs on the parliamentary seat of East Worthing and Shoreham, which throughout its various iterations has been Tory since 1876. This summer, Labour’s candidate Sophie Cook doubled the vote her party had notched up just two years before. And that’s just the beginning.

Along the seafront in Hastings and Rye, Labour came within a few hundred votes of dislodging the Home Secretary Amber Rudd this June. In once-marginal Hove, the Labour MP Peter Kyle went from clinging on by his fingernails to a majority of nearly 19,000.

The winds of change are blowing along the Kent coast too, from fashionable Whitstable (part of the Canterbury seat, which has just gone Labour for the first time) to fast-gentrifying Margate, with its new Turner gallery and cultural renaissance led by Tracey Emin. It’s happening in small towns away from the coast like Reading, as well as outer London suburbs like Croydon and Chingford. If those names sound weirdly familiar for some reason, it’s just possible you’re a middle-class London parent recognising all the places your friends moved to after they had children.

***

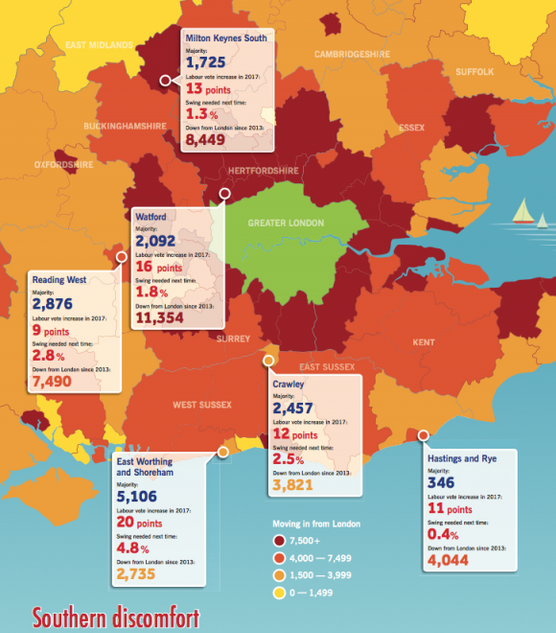

Meet what Peter Chowney, who so nearly won Hastings for Labour, calls the “Down From Londoners” (DFLs): middle-class professionals in their 30s and early 40s priced out of the capital and foraging across the southeast for family houses near good schools that they might actually be able to afford. Some are commuting long distances, others taking advantage of the growing trend to work from home. But together with their cousins the “Over From Brightons”—fast colonising that city’s cheaper seaside neighbours—they’re starting to redraw the electoral map. Around 1.3m Londoners have left the city in the last four years and an analysis last month by Ian Warren, a political consultant who worked for Labour at the last election, shows some intriguing overlaps between this wave of migration and June’s results. DFLs are bringing liberal views and votes into what were once profoundly conservative communities, and what’s striking is that much of this change has happened under the radar. Labour candidates achieved their swings in places like Worthing and Hastings even without the extra money, helpers or high profile visits the national party usually puts into winnable seats, because they were thought unwinnable. (The mistake is unlikely to be repeated: Jeremy Corbyn has visited both seats since the June election). The media were focused on the struggling, Leave-voting northern cities that had proved crucial in understanding the Brexit referendum. Nobody was looking at these new southern hotspots, where activists kept knocking on doors they thought belonged to pensioners and instead finding young, left-leaning families just moved in from Hackney. There’s nothing new, of course, about young urbanites leaving the city when they start having children. But in the past, that move to a more settled small-town life was associated with becoming more conservative, with both big and small C. Not anymore. The Tories were ahead among 35 to 44-year-olds in 2010; this summer, they lagged Labour by 16 points in the same age group. DFLs may be relatively well-heeled but as one cabinet minister puts it: “the big dividing line now isn’t income, it’s values.” Age, university education and even how you score on traits such as being liberal or authoritarian, nationalist or rootlessly cosmopolitan are becoming critical in predicting voting patterns. And Theresa May’s jingoistic campaign was anathema to these younger, often graduate couples moving out of culturally diverse cities. The DFLs tend to be horrified by Brexit, and more worried about funding cuts in their children’s schools or the social impact of austerity than about immigration. They’re not the only factor behind Labour’s southern resurgence, and the DFL effect didn’t work everywhere. But then it doesn’t have to, when Jeremy Corbyn is only a few dozen seats away from Downing Street.***

When John Moss, a Tory councillor in Waltham Forest, bought his first home in the area back in 1993 it cost him £70,000. Today, he reckons the same small terraced house on the suburban fringes of London would be worth half a million—although that’s still cheap enough to draw in young couples. “The change we’ve seen is young people doing what young people do; moving from rented rooms in shared houses to one or two bedroom flats, and having children,” says Moss, whose patch lies in Iain Duncan Smith’s seat of Chingford and Woodford Green. “But we’ve also got lower income households in the suburbs and their children can’t afford to buy… The income profile is changing with that, it’s a bit more professional, more public sector. Once an exodus of older, poorer residents and an influx of those able to afford £500,000 houses would have made a neighbourhood fertile ground for Tories. But under Corbyn, gentrification doesn’t work like that. In several southern seats it was working-class voters, suspicious of his views on immigration or defence, who hung back and middle-class graduates who swung to Labour. If anything an influx of good coffee and craft beer is now an ominous sign for London Tories, which helps explain why Duncan Smith’s majority fell below 3,000, pushing him towards the top of Corbyn’s target list. At a fringe meeting on London at the Conservative conference, speaker after speaker told the same story: Labour is coming for them, even in their suburban bastions. High rents and house prices are pushing millennials further and further out, changing the nature of formerly safe Conservative seats. Among those publicly raising the alarm is Syed Kamall, the London MEP. He was part of a small unit at Conservative Party headquarters studying demographic change in the run-up to the last election and says it helped him understand some of June’s more surprising results. Labour voters are clearly on the move, he says, but the question is why, unlike previous generations, their voting patterns aren’t changing as they go.The six seats that should worry the Tories