It was obvious that debating free movement and border control after the referendum was never going to be a reasonable or dignified conversation. But there is something conspicuously unhinged about the tone of recent discussions about migration—and it appears to be catching.

We are used to the buffoons of Brexit sweeping basic economic realities aside in the delirious pursuit of some Cotswolds-Xanadu free trade fantasy. What seems new is the extent to which otherwise quite reasonable and imaginative commentators—including some from regions of the Labour Party that are not even purple, let alone blue—are willing to go similarly evidence-free when it comes to talking about freedom of movement.

It doesn’t seem to matter how many times economists like Jonathan Portes patiently explain that the evidence for migrants under-cutting wages and taking jobs is, at its very, very, best, inconclusive; apparently we must now make policy as though it did. In September, Portes’ colleagues from King’s College London also helpfully explained why staying in the supposedly oppressive single market, custom’s union, or even the EU, would, at the very, very, worst, have a negligible effect on all 26 of Labour’s economic plans, including re-nationalisation—to apparently little avail.

Like persuading a smart PPE student that no matter how great he is at politics and philosophy, he still needs to pass his first-year economics exam, it is proving hard to get the mundanely self-evident facts of economic and political reason to temper, let alone ground, the self-confidence of either Brexit- or Lexiteers.

To an extent, this is not a surprise. It is not a readily known reality that is at stake in these debates. What we’re really talking about when we talk about free movement is not economic practicality but Britain itself: its borders, people, moral life, and history. This is why so much political talk about free movement is resistant to reality testing: all the time we’re discussing the best and most reasonable approach to border-control, we’re also scrapping over what kind of national fantasy we think it would be nicest to collectively inhabit just now.

This aspect of the debate is not, of course, new, and a bit of history can tell us why playing fast and loose with facts and fantasies about migration is always about something far more profound, and sometimes far more deadly, than (as Brexit enthusiasts on both sides of the house would have us believe) tidying up the excesses of an immigration policy too far gone to the globalized bad.

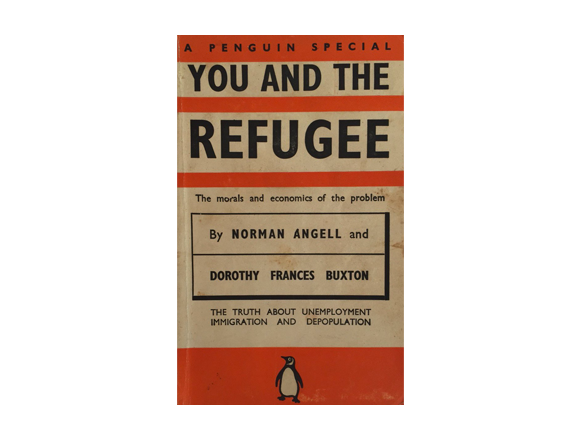

In 1939 Norman Angell and Dorothy France Buxton published a book with Penguin, You and the Refugee. Buxton was one of the founders of Save the Children, and had an interest in matching humanitarian impulses with enlightened self-interest arguments. Angell—English lecturer, economist, writer and one-time Labour MP for Bradford North—had long understood that the realities of global trade had complicated the politics of modern European nation states. One of the first to recognize that a “nation’s political and economic frontiers do not now necessarily coincide,” his previous popular 1909 book, The Great Illusion, made the creative argument that greater integration between European economies could eventually lead to the abolition of war. Forty two years, two world wars, and a Holocaust later, much of Western Europe conceded that he might have a point.

Then, as now, Angell and Buxton were writing when war, death, and destitution, as much as opportunity, were pushing people to Britain’s shores. In terms with which Portes and first-year economics students will be familiar, they argued that it was a fallacy to think of migrants in the labour market as a competitive “static lump,” apparently unattached to other bits of the economy. Instead, both migrants and refugees should be welcomed as potential economic assets, generators of consumer demand, businesses, jobs, taxes, and skills.

Even if the undercutting wages and jobs argument were true, they wrote, it is never OK to argue that “[b]ecause the competition of the refugee might injure me, let him be killed, or tortured, or imprisoned.” Except, in some insane way, it swiftly turned out to be fine to create a political culture hostile to both refugees and migrants that tacitly—and effectively—endorsed just the monstrous logic of just that thinking.

One year later, the internment of German and Austrian exiles began, and the doors to fleeing refugees, never open that wide in the first place, were closed further. In the autumn of 1940, Yvonne Kapp (best known as Eleanor Marx’s biographer) and Margaret Mynatt wrote a book endorsing the economic case put forth in You and the Refugee, and pointing out that it was antisemitism, xenophobia and an out-of-control nationalism that were really driving migration and refugee policy. The ethno-nationalist cat was out of the political bag. Yet Penguin dropped the book before it was published; Kapp and Mynatt had already lost their government jobs working with refugees because of their political views.

It was a refugee, the political philosopher, Hannah Arendt, interned by the French in the same year, who grasped the bigger picture here. Once nationalism has taken over the political and juridical functions of the state, she later argued, then the prospects of living in a democratic rights-based nation become very bleak—for everyone. Hostile environments, as any gardener will tell you, are difficult to contain.

From within the maelstrom of their times, these twentieth-century thinkers diagnose the dilemma behind our current, reality-resistant, border anxieties. Because global economies do not just create capital, but sequester it, so also creating a dangerously and violently inegalitarian world, we need political institutions to check its excesses. The nation state is good for this, and good, too for giving collective meaning to our lives. A comity of nation states committed to regulating the world economy whilst enforcing mutual sovereignty is probably about as good it gets—or at least, so it appeared to the war-weary of the last century.

The reality of the European Union has proved itself inadequate to this aim, but it does not follow that a retreat into nationalism is the answer—particularly when what currently counts as the “national interest” treads so lightly on evidence and reason. In any case, as historian Timothy Snyder argued recently, you can’t enforce the norms of territorial sovereignty with a fantasy.

Writing just after the war, amid a resurgence of antisemitism and anti-migrant feeling, George Orwell wrote of the great “moral effort” needed to face-off the reality-denying seductions of nationalism. If there is one lesson worth heeding from the 1940s now, it is that we urgently need to turn that moral effort into a reasoned and evidence-informed political project.