One of the most discussed aspects of this general election campaign has been the way the young vote. How are they likely to cast their ballots? Will as many vote as say they will? What does this mean for the outcome on 8th June? Underlying these specific questions are fundamental questions about voter behaviour. Here, we’ve gotten stuck into the data to identify the key trends.

Generational differences are increasingly seen as a key political divide. There have been stark age gaps in each of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the 2015 election general election, and most notably in the EU referendum. Together, these create a sense that the real chasm in British politics is now between young and old.

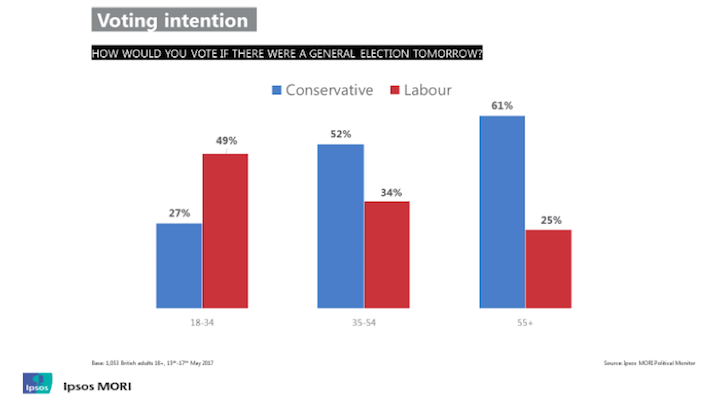

And it’s proving the same for the 2017 election, as the chart below shows: support for the Conservatives doubles from young to old, and halves for Labour.

And it’s not just on party support that the generations seem polarised—it’s also on whether they vote at all. There is a curious narrative of blaming the young’s apathy for Brexit and, more broadly, their own woes as a generation: if they were more of a voting force, they’d be less screwed on student fees, house prices and paying for their grandparents’ triple-locked pensions.

But these descriptions are very static, and often muddle age and generation effects. The much more important question is whether these patterns have always been a feature of youth, or whether it’s something about this particular cohort of young people—or Millennials, the almost always derogatory label for the current generation of young people, born from around 1980.

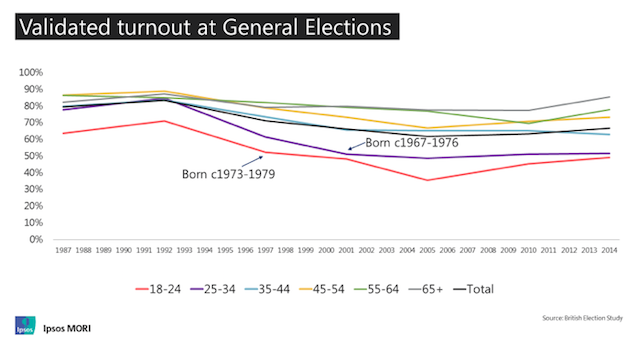

First, this current generation of young people does vote less—but as the chart below shows, the real break in voting levels started with the previous cohort, Generation X (who were born 1966-1979).

Our new reanalysis of the British Election Study shows that there was a big drop in the relative turnout of 18-24 year olds at the 1997 election—a group that would have been born in 1973-1979. And this has slowly crept through the age spectrum as this Generation X cohort has grown up: by the 2001 election, this Generation X group had continued with their low level of turnout, despite being 25-34 years old. And the pattern has actually been pretty stable since (after a blip in 2005): Millennials are more or less matching Generation X’s turnout at a similar age.

When they do vote, it is clearly true that young people are much more likely to vote Labour. But is this a feature of youth, or are they a more left-leaning cohort that will take those views with them? Or does the aphorism, attributed to everyone from Clemenceau to Disraeli and Churchill, that you have no heart if you’re not a socialist under 25, and no head if you’re still one at 40 reflect how people change as they age?

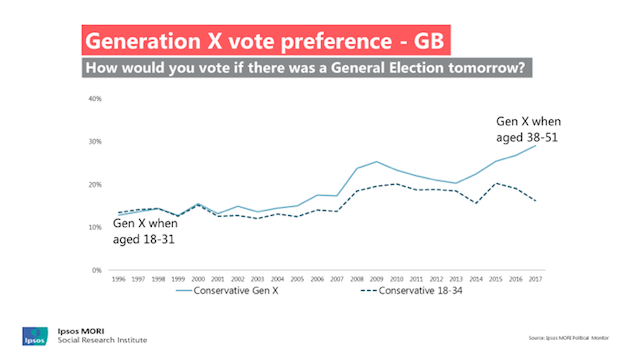

Our new analysis of our own huge dataset back to 1996 suggests that there is still some truth in this very old adage. The chart below tracks Generation X over the last twenty years, starting when they were fairly new to voting, aged 18-31, and following them all the way till now when they are more middle-aged.

Alongside this we’ve plotted 18-34 year olds as an age group—and you can see how significantly the two lines diverge. Today’s 18-34 year olds aren’t much more likely to vote Tory than 18-34 year olds in 1996, at around 16 per cent. But Generation X have moved from 14 per cent saying they will vote Conservative to 29 per cent now—it’s doubled as they’ve aged.

So turnout is generational, but Millennials didn’t start the decline—and party support is strongly driven by age, so is likely to change over a lifecycle.

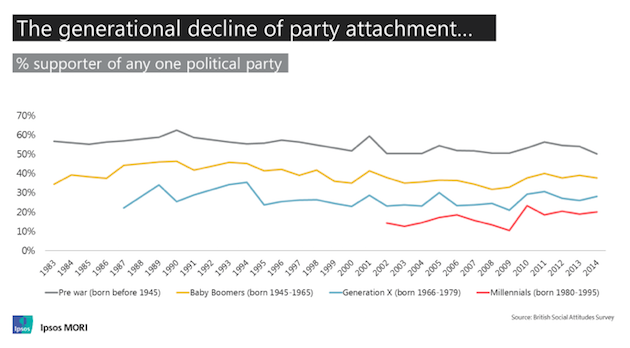

But there is a third pattern that is truly generational and looks unstoppable—the decline in connection to political parties more generally. As the chart below shows there has been a remarkable fall between the generations in saying they feel close to one particular party.

Around 60 per cent of the pre-war generation see themselves as a supporter of one party, and that is incredibly flat over time, all the way back to 1983. Around 40 per cent of Baby Boomers say the same, and again this is virtually unchanging. There is another steep drop down to around 30 per cent of Generation X saying they are close to a party—and down again to Millennials where only around 20 per cent say the same.

This doesn’t mean that each generation is less interested in politics, but it does mean that automatic support for individual parties can no longer be relied on—and it’s only going to get worse. In fact, the generational lines are so stable that we can roll them forward, and predict confidently that under a quarter of the whole population will feel attached to a particular party by the time of the next (scheduled) election in 2022—down from over 50 per cent in the 1980s.

Unpicking these age and generation effects is therefore vital, as it helps predict the future. And this analysis suggests three things.

First, Millennials will increasingly flex their political muscle and parties will need to better reflect their concerns: they’re a big cohort and while their voting levels are lower, they’re not that much lower.

Second, Millennials are unlikely to be innately left-leaning throughout their lifecycle. In fact, older members of the cohort are already following a similar pattern to previous generations.

But third, the days of bloc connection to political parties are on their way out, only propped up by an older group that is diminishing rapidly. This points to a more fluid future—an opportunity and challenge for parties, and a nightmare for pollsters!

Ipsos MORI has conducted a detailed review of evidence on Millennial Myths and Realities.