Will it be sixty billion euros, one hundred billion or not a brass farthing? As so often when money is involved, the rhetoric around the likely “divorce” bill for the UK to leave the European Union has become increasingly poisonous, despite the fact that no official demand from the EU side has yet been put forward. Equally, the UK has yet to make an opening offer.

Nor is the legal position as clear as the protagonists assert. The House of Lords European Committee caused a stir by saying the UK could walk away with no obligation whatsoever, a verdict welcomed by the government. Legal advice to the EU institutions takes an opposite view. Both extremes, in practice, are largely irrelevant, unless the negotiations degenerate into so hostile a Brexit that it ends not around the table, but in the courts.

There are several potential components of a Brexit bill. Although complex and messy, they boil down to a handful of conceptually distinct elements.

The first is commitments already made by the EU or due to be made before the date of Brexit, known in Brussels-speak as reste à liquider (RAL), meaning “still to be settled.” These commitments arise because many of the EU’s programmes, especially for research and regional development, are multi-annual. Typically, projects will receive a proportion of their money at the outset, but will—quite properly—only receive final payment when the project is completed. For example, there might be funding for new transport links that take several years to build, with binding contracts signed in 2017, but only concluded in 2021.

Second is the fact that the EU budget is set in a seven-year framework lasting from 2014 until the end of 2020, with the broad headings of expenditure agreed in a Council regulation dating from 2013. This is a legal act, approved by the two legislative bodies of the EU—the Council of Ministers (including the UK) and the European Parliament. Some on the EU side, especially the net recipients from the budget, argue that the UK is liable for the full seven years, irrespective of when Brexit occurs. On the assumption Brexit is completed by the end of March 2019, the implication is the UK will still have to pay its share for the remaining seven quarters, that is from April 2019 until the end of 2020.

The third element is longer term obligations, especially the pensions of employees of EU institutions who retire while the UK is a member state, a proportion of whom are British citizens. In the EU’s accounts, there is a figure for the implicit pension pot needed to pay the future pensions, and one possibility would be that the UK buys out its share of this pot.

Offsetting this is EU assets purchased while the UK has been an EU member. It could be argued that a proportion of these should be distributed to the UK, although new members joining the EU are not asked to pay up-front.

Fifth, some of the money for RAL, future EU programmes and pensions would, if Brexit did not happen, have been spent in the UK. EU spending in Britain has run at around €7bn per annum recently, and deducting these payments would reduce the bill substantially.

The most comprehensive study published so far, by researchers from the Bruegel think-tank, shows the huge range of possible estimates. According to the authors, the bill could be between €25.4bn and €65.1bn net, depending on the scenario. They also note that the UK might be asked to pay earlier and only receive some of the “money back” later, although it is hard to see such a deferment as being a politically credible outcome.

The calculations unequivocally demonstrate that any answer has to start by recognising it depends on the composition of the eventual demand. In short, there is enormous scope for negotiation. The wide range can be explained simply: it depends on what to include or exclude, and then on the proportion of the total in question (for example of RAL) to be charged to the UK. The latter, in turn, is linked to what the UK pays at present.

The Treasury’s most recent annual overview of EU finances was published in February. It explains the different approaches to estimating what the UK pays and receives, while also revealing how erratic the numbers can be. In 2015, for example, the UK “sent” £14.65bn to Brussels, slightly up from the figure of £14.36bn in 2014, but this fell to £13.12bn in 2016. For those who recall the now notorious promise of £350m a week for the NHS, the corresponding figures are £276m in 2014, £282m in 2015, then down to £252m in 2016

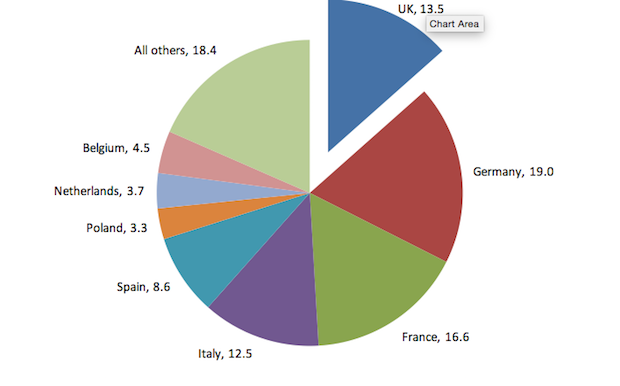

The UK’s share of the aggregate in 2016 was, as the chart below shows, 13.5 per cent—higher than the 2015 and 2014 figure of 12.6 per cent and 11.0 per cent respectively (according to the earlier editions of the Treasury overview).

Contributions to the EU budget (share of total after all rebates, percentage, 2016)

Source: HM Treasury and Office for Budget Responsibility

These fluctuations underscore how tricky working out the divorce bill will be. Using the 2016 share would result in a demand more than 20 per cent higher than the 2014 share. Conversely, basing what the UK owes on the 2016 actual payment to Brussels would mean a significantly lower figure.

One of the main reasons this is so contentious is that if the UK does not pay, someone else will have to pick up the tab. For the Germans, already gearing up for a difficult election, this would be particularly delicate.

What, therefore, would be a reasonable amount? No one really knows—it is after all a negotiation on many fronts, and it must be expected that a satisfactory outcome on the money will influence other dimensions such as the quality of a trade deal.

Best guess? Somewhere around the €30bn mark…

Iain Begg is a Senior Fellow of The UK in a Changing Europe and Professorial Research Fellow at the European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science