The Peterborough by-election was the opposite of Alice in Wonderland’s caucus race. Instead of the Dodo announcing that “everybody has won, and all must have prizes,” the returning officer in the early hours of this morning might as well have said: “nobody has won, and none shall have prizes.”

To be sure, Lisa Forbes will take her seat next week as Labour’s newest MP. Jeremy Corbyn will feel that he has a bit more breathing space to pursue his stance on Brexit. However, a 17-point drop in Labour’s vote share since the last general election should strike terror rather than offer reassurance.

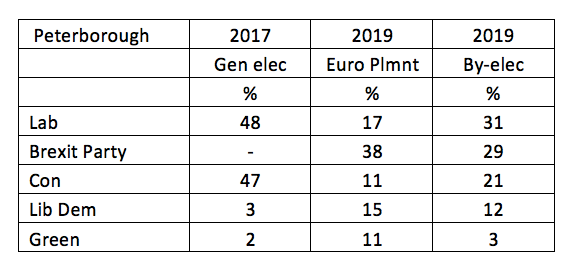

The table below shows the key figures. If last month’s European Parliament election is taken as the baseline, Labour and the Conservatives have both done rather well, with big increases in their vote share. However, the more relevant comparison is with 2017. Two years ago, the combined two-party vote share was 95 per cent. Yesterday it was 52 per cent. The result confirms the large story from the opinion polls as well as the European Parliament elections: there is huge public dissatisfaction with both main parties.

The reason Labour held the seat was not because the party is locally popular—it isn’t—but because the right-of-centre, overwhelmingly pro-Brexit, vote was more evenly split than the left-of centre, mainly anti-Brexit, vote. A total of 17,444 people voted Brexit Party, Conservative or Ukip, while 15,678 voted Labour, Liberal Democrat or Green. But, while Labour attracted 67 per cent of the left-of-centre vote, the Brexit Party won just 56 per cent of the larger right-of-centre vote.

Of course, to say that the Brexit Party won “just” 56 per cent of the right-of-centre vote doesn’t really do justice to the number of votes that a party managed to garner just weeks after its formation. Even if we regard the party as the current vehicle for Nigel Farage’s career, rather than a wholly new force, it still did far better than Ukip managed to in most past by-elections in Labour constituencies. Between 2012 and 2017 it typically won around 20 per cent in such seats; the only by-election when it topped yesterday’s share was Heywood and Middleton in 2014.

However, there are times when statistics don’t tell the most important story. The more important point is that Brexit’s Mike Greene narrowly lost last night. Had he narrowly won, the figures would have been much the same but the consequences very different. The Brexit Party would have a voice in the House of Commons. The momentum from the European Parliament towards a possible break-up of the two-party system would have been maintained.

Instead, the prospect of a Brexit Party breakthrough in an early general election has receded. Like the Liberal/SDP Alliance in 1983, when 26 per cent of the national vote share secured it just 23 MPs, the Brexit Party is likely to be crushed by the first-past-the-post voting system, winning millions of votes but very few constituencies.

If that thought comforts the Tories, they should beware. The danger they face is that, as in Peterborough, the Conservatives will lose more votes to the Brexit Party than Labour loses to the Lib Dems and Greens. The impact of this could well be to cost the Tories victory in dozens of Conservative-Labour marginals, and make Corbyn prime minister.

One final point. As a recovering pollster, I am frequently irritated by people who say the betting markets provide a better guide than the opinion polls. Given that poll figures usually inform the betting markets, this is not easy to test. However, it’s worth noting that, in the absence of local polls, the bookmakers got the Peterborough by-election hopelessly wrong. They made Mike Greene the four-to-one-on favourite—just as, four years ago, the bookies gave Corbyn little chance of becoming Labour, until a YouGov/Times poll showed him clearly in the lead. As I used to write at the end of answers to many maths questions in school exams: QED.