London calling? Earnings in the capital and beyond

London has often been a byword for wealth in provincial England—which is why we remember Dick Whittington not just for his cat but for London’s supposed “streets of gold.” But how true is this?With so much trade and finance centred in London, property prices have always been higher, and—when so much wealth is tied up in bricks and mortar—that means there is indeed a wealth gap between London and the rest of the country.

In the average wealth figures, this spills over into the capital’s southeastern hinterland, where a somewhat older population has had more time to build up more wealth. Furthermore, over the long years in which (until very recently) house prices surged in Walthamstow while stagnating in Wolverhampton, the regional gap tended to widen.

Compared to the period just before the financial crisis (2006-8), typical household wealth in London is up by 62 per cent in real terms, compared to a rise of just 10 per cent across Great Britain. This matters. Much of the worldwide increase in wealth—and the danger of it being concentrated in fewer hands which Thomas Piketty worries about—is due to the rocketing value of scarce land in globally connected cities.

None of this means the streets are paved with gold for all Londoners, any more than for Dick Whittington. High average wealth in the capital hides spectacular inequality. Aspiring home-owners, for instance, are missing out. As recently as 2000, it took the average young family just five years to save for a reasonable deposit; today it would take them 35 years to accrue what they’d need—by which time our “young family” would be ageing empty nesters.

More generally the divide between the haves- and have-nots of London is at least as important as that between the metropolis and the rest. Poorer London households (the 25th percentile of the wealth distribution) actually have less in total wealth (£35,000) than those in the same position in the rest of the country (£61,000).

Paved with gold? Wealth in London and Britain

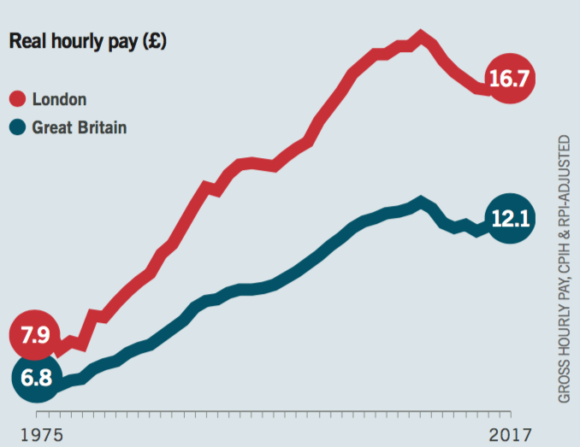

These big pay gaps partly reflect qualifications and the jobs on offer. Nationwide, 28 per cent of working-age Brits have a degree, but among working-age Londoners it is 43 per cent. Scientific and professional roles are more common in the capital, occupying 15 per cent of workers, but only 8 per cent of those in other big cities.

Likewise 8 per cent of London’s workers are employed in IT and another 8 per cent in finance, compared to just 3 per cent in each of the two sectors in the other cities. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, London actually saw a bigger pay squeeze than the rest of the country, but looking further ahead, divergent results in the schools system give reason to fear that the regional gulf in earnings could become entrenched.

Results in London schools have improved hugely over recent decades so that today the proportion of London school children who get a “good” GCSE in English and Maths is around 9 points higher than the rest of England.

But higher pay in the capital doesn’t necessarily mean that ordinary Londoners are cleaning up. Pay inequality is higher in London—someone near the bottom earns only a quarter as much as someone at the top of the pack in the capital, whereas the lower-paid in the rest of the country earn a third as much as their better-off counterparts.

And prices are higher in London—especially for housing. The average Londoner spends over a quarter of their income on housing, compared to a sixth for a household in the rest of the country. Londoners renting in the private sector spend nearly half their income on rent.

So costly is London housing that Londoners actually don’t have higher living standards than the country as a whole. Indeed, thanks in no small part to rents that until recently were running away, disposable incomes for working age households are today no higher than they were 15 years ago.