Britain was once full of glorious towns—regency spas, industrial workshops, market squares, council chambers, grand town halls looked down upon by statues of local dignitaries. This was the very fabric of the nation of England, in particular. It is an intriguing parlour game to take a description like the one that follows, from Mark Girouard’s The English Town: A History Of Urban Life, and wonder to which place it applies:

“For a mile or so we drove along a street of palaces—palaces… amazing in the height and power of their mighty stone façades, piled up storey after storey, and row after row of windows. I have never been to Florence, but this, it seemed to me, must be what Florence is like.”

Answer—it’s Huddersfield. For that, town though it is, was his “glorious city” of palaces and façades of high windows. Some of the buildings on the streets leading out from its St George’s Square are indeed splendid, but The English Town was a deeply nostalgic tour of such places even when it was published in 1990. After the passage of a further quarter-century—a quarter century that has, in sequence, seen suburbanisation, out-of-town shopping centres, a financial crash and then internet shopping going mainstream—it sounds like a relic from a lost golden age.

The last generation has witnessed a remarkable story of progress in the big cities. Immigration has brought a new energy and diversity—new businesses, foods and fashions. Universities have expanded out of all recognition, bringing a young population that needs to walk, rather than drive, into their centres. Train travel, which had been dying, has become vastly more popular, laptops and then smartphones enabling people to work on the move on their way into the heart of a metropolis. The fashion is increasingly to live in the city, perhaps in one of the endless canal-side former factory conversions where one can hope to meet, work with and date other like-minded sorts.

The cities, then, have undergone a renaissance. Not so the medium-sized settlements in the Huddersfield mould, including the place where I was raised—Bury, so close to Manchester, and yet so vigorously separate from it. How then can the Huddersfields and Burys replicate the successes of the Manchesters? To answer that we first need to understand how and why the paths of towns and cities have diverged so dramatically.

*** In the 1800s, as the Industrial Revolution took hold, the town of Bury and the city of Manchester could both lay claim to prosperity and success. In the 1900s, they would also know hard times together. The decline of the old industrial base had set in by the turn of the 20th century and things got worse—much worse—during the 1920s and 30s. With the help of a lot of economy-wide and industry-specific intervention, the urban rot was arrested for a time in the 1950s and 60s. But by the 1970s, things were coming unstuck again, and the long descent hit rock bottom during the 1980s.

A whole culture and community was dismantled with the collapse of heavy manufacturing—and the collapse was, if anything, now most marked in the big cities than anywhere else. Over long post-war decades, great cities like Liverpool were continually shedding population; right through the 1960s and into the 1980s, even London itself was hollowing out, losing population to the commuter new towns and small towns that were then seen as the future. Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield, Newcastle and Birmingham were all left in a poor state. Badly led—in the case of Liverpool under the Militant tendency, ultimately catastrophically led—and struggling to find an economic rationale, the shadows were falling on British cities. The phrase “inner cities” became a euphemism for poverty, crime and racial tension.

In the later part of this period, as a boy growing up in Bury, the city of Manchester was the first that I explored alone. There is something incredibly invigorating about the city in which you learned how to navigate. I looked on it with wonder, even though it was a poor and forbidding place whose tone was one of defiance. It seemed a place whose great days were in its past.

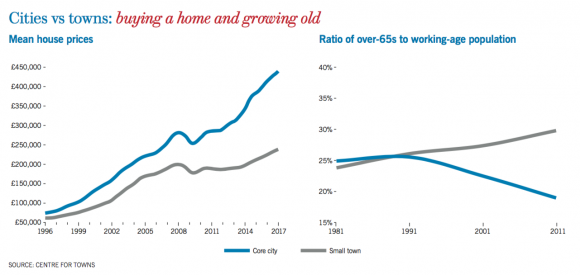

In more recent years, though, you don’t need to be a youngster in awe of his first metropolis in order to marvel. Cities have been growing younger and more vibrant, while the towns have aged. The last four years in particular have brought the political division between nostalgic towns and “progressive” cities into stark relief. In 2015, Ed Miliband’s Labour advanced in London and other conurbations, but faltered in small-town England, losing seats in places where Ukip soared. In 2016, the referendum reinforced the schism: Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and most especially London voted to “Remain” while the patchwork of smaller settlements swung the country for “Leave” (Manchester was 60 per cent “Remain,” Bury 54 per cent “Leave”).

In 2017, the Labour surge in the cities was such that even true-blue Kensington fell, while the Conservatives were actually able to take Labour Mansfield. Then, just this spring, we saw Labour make yet more strides across the capital—piling on councillors, if not whole councils, as the Conservatives lost Trafford on the affluent edges of Manchester. But places in the small-town Midlands, such as Dudley, swung the other way.

Provincial high streets lined with charity and pound shops don’t help and they make for an increasing contrast with the pop-ups and glitzy chains of the city centres. When it comes to house prices, the cities have once again cleaned up. Between 2006 and 2017, property values in London doubled. In the same period, the average house price in Bury crept up by under 2 per cent on average annually, the total rise from £145,000 to £170,000 representing a drop in real terms.

For those with a stake in property in prosperous cities, that bred faith in the outward-looking economic order that has rewarded them, and that included the EU. London’s burgeoning renters, of course, had a different experience, but perhaps even they had the faith that if they could stick around and somehow get a foot on the ladder, they might one day get a share in those streets that were paved with gold. But people in the towns didn’t share those rewards—or that outlook. They don’t feel, as many city-dwellers do, that they’ve got any sort of stake in a more prosperous future.

After a long absence, I have been spending more time in Bury lately, at the invitation of Rishi Shori, leader of Bury council, as chair of a commission into the life chances of the town’s people. On my way to Bury I pass through Manchester, a much-changed place. Gone is the forbidding city, replaced by a lighter, more prosperous European conurbation, in which work is plentiful and play is good business. Inventive statecraft has helped, under the guidance of Richard Leese, leader of the city council, and, until recently, Howard Bernstein, chief executive. Business investment and innovative design such as Daniel Libeskind’s Imperial War Museum North have also lifted Manchester. Between 2001 and 2011 the population increased by 20 per cent. The equivalent number for Leeds was 5 per cent.

The renaissance is visible everywhere not only in these three cities, but also Liverpool, Newcastle, Sheffield, Birmingham, Glasgow and Edinburgh. What you notice, though, as you leave Victoria Station in central Manchester is that the benefits do not stretch far.

I travel through a familiar scene: Cheetham Hill, Crumpsall, Heaton Park, Prestwich, Besses o’ the Barn, Whitefield, Radcliffe. I am surprised nobody has ever written a Manchester to Bury tram version of Route 66 and even more surprised that Mark E Smith, our resident celebrity when I was young, never got around to writing it.

*** Manchester’s recent regeneration has not trickled across to Bury. Even so, my home town is by no means a problem place—it is in better shape than other northern towns like Blackpool or Barnsley, which don’t have the same proximity to any humming metropolis. Bury has undergone an economic transformation of a sort. But its manufacturing employment has fallen by 41 per cent since 2005, a far higher drop than the national average and it is now a service-sector town.

To a dismaying extent the service industry is dependent on public spending—and therefore government whim. A fifth of the workforce is in health and social work; almost as many, it is true, are in wholesale and retail, but work there has often stopped paying. In Bury, real median hourly pay has fallen by 80p per hour (7 per cent) since 2008. As the number of hours worked has also fallen, annual real pay has fallen by even more: £2,700 a year (10 per cent). There are parts of Bury—Radcliffe, Moorside and East wards—that are among the most deprived in the country.

But there are upmarket wards too and the combination of the really dreadful with the lovely means that Bury is an average sort of town. The headline numbers for education are roughly in line with the national average, yet too many children are turning up for their first day at school not ready to learn. A significant minority of pupils get through 11 years of compulsory schooling with nothing to show for it.

The most radical initiatives in school reforms—think of the early academies—have generally been aimed at the inner cities more than the towns; and the reforms of schools and universities have done far more for the sorts of people who will leave the towns, people like Robert Peel and me, and not much of it has benefited the people who will stay. Back in Bury, aspirations for many children are low and their horizons too narrow. This is in part a problem of poverty and the lack of high-quality work, but it is also psychological.

Struggling parents in Bury need practical help, and its young people need better mentoring and careers advice. It needs a different type of educational provision: less academic, more technical—the whole country would benefit from that. The pressing question is therefore not how Manchester can be even better, but how Bury can create its own success.

The problem of state-led regeneration goes deeper than austerity, although the savaging of local government budgets hasn’t helped. Unlike NHS budgets or pensions, local spending was not protected. There is also a paradox here contained in the figure of George Osborne. From 2010 on, he slashed local authority budgets, but his later Northern Powerhouse reforms, and the establishment of city mayors, has promised new powers to the locality from the most centralised of developed states. But there is a danger the new metro-mayors will hand all influence to the big cities, at the expense of outlying towns.

Besides, local powers are only useful if they are used properly. Time and again while gathering evidence for the Bury Life Chances Commission, we found a hole where there should be an effective national policy, especially in respect of infrastructure and skills. The towns of Britain will not be revived without fixing this, and cash-strapped local government can’t do that alone—even if it is revivified with new powers. It is only at the national level that the power exists to lay rapid train lines, site airports or build trunk roads.

Public resources are inevitably part of a more promising regeneration story—but they cannot be the end of it. This might not seem an auspicious field or moment for the intervention of large corporations, but imaginative work between the public and private sector has to be another crucial element. At the absolute extreme end of the scale of regeneration, in Detroit, Michigan, JP Morgan Chase has been showing what can be done with deep commitment and deep pockets. It’s a huge city and the collapse of its industries and population has been astounding, going back much further than the relative and more recent eclipse of England’s smaller towns. But there are wider lessons about regeneration here—especially for Bury—which can, in a small way with the Commission, now hope to benefit from some of the same energy and focus.

Led by its CEO Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan has committed $150m to Detroit. But the key is that JP Morgan is not doing regeneration to Detroit. In partnership with the Mayor it is sponsoring voluntary and community organisations to lift the city. Their efforts are concentrated on property development, small business generation and training. The representatives of the neighbourhoods themselves decide where the money goes.

*** Regeneration is, like community, one of those abstractions that is better approached from the side. It is not really a thing in itself but the upshot of other things. Until now, policies in this field have delivered physical results that have been imposed remotely, but which are not remotely wanted.

This raises the question of how to get schemes led by the people themselves. And here a different type of private-public co-operation—this time flowing the other way—comes to the fore. In straitened circumstances, local authorities would be well-advised to use their borrowing powers to invest in services (or businesses) that local people can run. The chances of devising sustainable services are considerably higher when the public are in charge. An inventive local authority could, with the right powers, shift from being a provider in the traditional way to becoming a social investor.

Where the ordinary investor is looking for a yield, the public investor takes a return that is in part comprised of the public good that is achieved. The proposal could, if pursued with ambition, revive something of the co-operative movement, pioneered in John Bright’s home town of Rochdale in the 1840s. (There is a very northern rival claim at Meltham Mills near Huddersfield, which claims to have beaten Rochdale to it).

There are many examples of such schemes already at work in Britain’s towns, but there should be more—and on a bigger scale. The Dolphin Pub in Bishampton is now run by residents with a loan from their public authority. The Cheese and Grain, in Frome, is a music venue and a social enterprise. A former agricultural market hall, it now has a favourable lease with the town council, which also provides working capital that it takes from the Public Works Loan Board at very low interest rates.

In the absence of banks showing much interest in small towns, Frome Council is, in effect, borrowing from central government and lending the money on. It is acting as a money broker, making something happen that it would struggle to provide. In a sense, the local authorities are performing the role once played by the local banks that have long-since been swallowed up by the giants of Canary Wharf—giants that have not for the most part been kind to England’s small and medium-sized towns.

Larger conurbations are also using this model. Portsmouth Council launched a £108m property fund in November 2015. It has invested £7.25m in a logistics warehouse in Yorkshire, £11.5m in a bed factory in the West Midlands and £16m in a retail park in Portsmouth. After costs, the portfolio has generated £4.3m profit for services which has benefited libraries, museums, weekly rubbish collections, community wardens, homelessness and school crossing patrols.

If David Cameron had ever given real meaning to the idea of the Big Society, schemes like this could have made up his agenda. Who knows, he might have survived the European Union referendum if he’d had the presence of mind to see it through. As things stand, time has run out on remote expertise, confidentiality and formal governance. This is the era of open participation, looser structures and popular power.

The work on the Life Chances Commission is just starting but the glory is that there is more and more evidence that real good can be done. If it can make a practical difference in Bury it might, in time, show the way for other towns to recover themselves too. But if we can start to help Bury, then that will the best work that I ever do.