Since the 2008 financial crash much ink has been spilled on the demise of the centre-left across Europe. Here in Britain it hastened the demise of New Labour, while in Germany it turned the SPD into a perennial junior coalition partner. They were the lucky ones. The once-dominant Pasok has been wiped out in Greece, the Socialist Party of François Mitterrand sunk to fifth at the presidential elections last year, while the Labour Party in the Netherlands slumped from coalition government to an embarrassing seventh.

The avowedly progressive side of the ideological spectrum is, perhaps ironically, always the more given to gloomy introspection. But this time its anguish appeared to be justified. For the best part of a decade after a crisis that exposed much that was rotten in the old order, events appeared to be playing out against those forces that wanted to reform it.

That pattern may have seemed surprising to some, but perhaps not to students of Britain’s political history in the 1920s, 1930s or indeed 1980s. Hard times once again appeared to be shoring up the establishment.

Meanwhile, support for the centre-right remained solid. For many years after the crash, the parties that helped forge the post-war “west” and have run it for most of the time since sometimes looked as strong as ever. Angela Merkel was able to increase her vote in 2013, a feat matched by David Cameron in 2015, when he succeeded in swatting the challenge from Ukip out of the way and winning an unexpected overall majority.

Other insurgent anti-establishment parties were, on the whole, being held at bay. Given the economic battering western democracies have faced since 2008, the resilience of the old political order was remarkable. But will this last much longer?

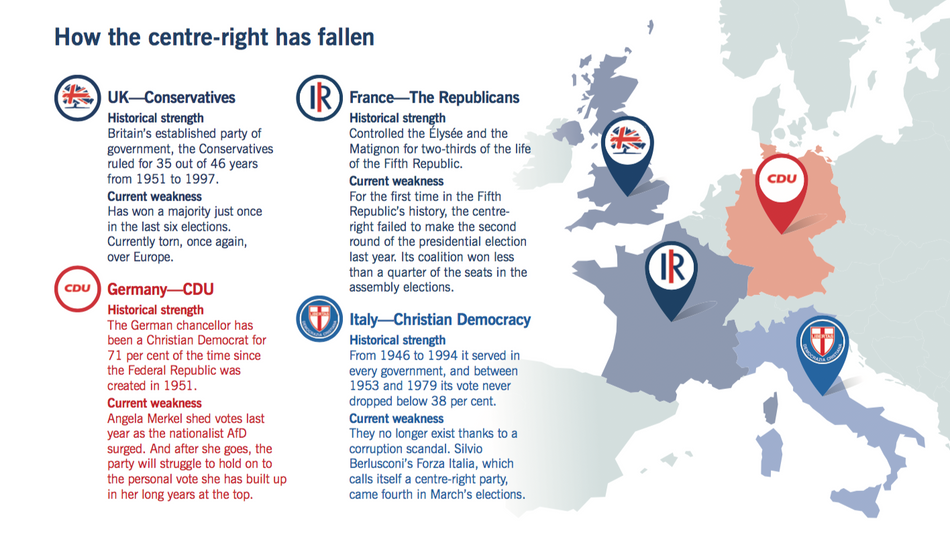

In the last year or two, elections—and in the UK a referendum, too—have begun to indicate that the centre-right forces, like their centre-left counterparts, are now on the defensive. In Germany, in France, in the UK and latterly in Italy they have proved unable to command majorities, and seen their core support shrink and with it their ability to form governments.

The arrival of the anti-immigration Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) to challenge Merkel is the perfect illustration of what is going on; new parties and movements, particularly from the populist nationalist right, have risen to challenge them across the continent. These paint centre-right parties as part of the cosmopolitan elite, committed to supranationalism and the global market and as much a part of the problem as the rootless centre-left. Some centre-right parties have aped the language and policies of the far-right, others have tried to stand firm for moderation; but almost all have seen their support slip.

Could it be that the solidity of the traditional centre-right was only the creation of specific historical circumstances? Specifically, the destruction of the main fascist regimes in the Second World War; strong nation states with settled borders in its wake; and, on the international stage, the idea of a western alliance. And, if the insurgents continue to make ground, might we see the demise of the forces of moderation and the return to a new era of nationalism and authoritarianism in Europe?

Rise from the ashes

The centre-right has been the dominant political force in many European countries for much of the last 70 years. Various forms of Christian Democracy proved particularly successful in Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries, while Gaullism often triumphed in France and the “One Nation” aspect of Conservatism was—in reality—always a huge part of the Tory coalition in Britain, notwithstanding Margaret Thatcher’s insistence that the middle of the road was a good place for getting run over.These were all different movements, shaped by particular national histories and institutions, but they also shared common ideas and common purposes. They were key architects of the new national consensus that helped to rebuild each country after the Second World War, and—more often than not—they continued to run their nations for many decades after that.

British Conservatives have occupied No 10 for 59 per cent of the period since the Second World War; until the rise of Emmanuel Macron last year, politicians of the French centre-right controlled the Élysée Palace for 66 per cent of the life of the Fifth Republic from 1958, and the Matignon for 67 per of the time; meanwhile, in Germany, the Chancellor of the Federal Republic has been a Christian Democrat for 71 per cent of the period since its inception in 1949.

These, then, were the parties that defined the political order. They were nationalist, but almost all of them (Gaullism was the big exception) were also Atlanticist. They were willing allies of the United States and participants in the new world order, with its institutions, alliances and its presumption for increasingly free international trade.

In domestic politics they all accepted a capitalist market economy but often allied with a strong belief that serious efforts should be made to spread the benefits of private ownership far and wide. They also accepted a significant role for the post-war state in providing universal basic services, and a welfare safety net.

The early years of reconstruction were hard in many countries but from the early 1950s onwards a period of unparalleled prosperity and economic advance began, over much of which centre-right governments presided. Industry modernised, education expanded, and—through rising wages, developing pensions and the growth of home ownership—the resulting prosperity was widely spread.

After the political traumas of the 1930s and 1940s, the moderate parties of the centre-right seemed to have found a winning formula. They were able to guarantee external security through the Atlantic Alliance and domestic prosperity through an expanding economy which delivered for the majority of citizens. A solid electoral bloc was created that made the centre-right parties the leading political force.

Their success was entrenched through the consensus formed with other democratic parties, particularly those of the centre-left. Although they remained fierce electoral rivals there was basic agreement on some key policies, particularly the Atlantic Alliance, anti-Communism, and Keynesian welfare state capitalism, and also on institutions and procedures that made liberal democracy possible, particularly the rule of law and civil, political and social rights for all citizens.

That meant that parties of the centre-right and centre-left could alternate in government and implement different policies without the foundations of the post-war order being called into question. Even Italy, where such smooth alternation in power was precluded because the perennial opposition was the Italian Communist Party, there was increasing co-operation with the Christian Democrats during the “historic compromise” of the 1970s. In the decades after 1945, every western European democracy reached its own historic compromise between rival political forces.

This political rapprochement within national borders also helped to enable an additional rapprochement across them. Leaders of the centre-right—Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet, Konrad Adenauer, Amintore Fanfani, Edward Heath, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, and Helmut Kohl—were also key architects of the moves to European integration which resulted in the creation of the European Community, the Common Market and eventually the European Union. Four of the six leaders who signed the Treaty of Rome in 1957 were Christian Democrats.

There were some dissenting voices on the centre-right, notably Charles de Gaulle, and in her latter years, Thatcher, but the great majority of centre-right politicians were supporters of the European project; they saw it as embedding peace and co-operation, liberal democracy, and shared growth and prosperity.

All the European centre-right parties were “catch-all” parties. They sought to make a broad national appeal in order to win as many votes as possible. This meant that they were themselves coalitions, sometimes with organised left and right factions, and always with different wings, which would wax and wane at different times. The parties were less weighed down by ideology than those on the left, and were remarkably adaptable to the circumstances of time and place.

For example, in Britain where the corporatist post-war settlement came economically unstuck earlier than most, during the 1970s, the Conservative Party evolved Thatcherism, the political programme I once characterised as the “Free Economy and The Strong State.”

Later on, many other centre-right politicians elsewhere on the continent—think of Nicolas Sarkozy in France—would experiment with the same blend as they sought to overhaul their own parties for new times.

As the economics of the centre-right became harder, there were attempts to soften its harsh edges—sometimes from within the bloc itself, and sometimes from outside. In the later 1990s, the centre-right was electorally eclipsed for a time by Third Way social democracy, and most EU countries had a centre-left government.

The Third Way introduced some distinctive policies aimed at promoting greater social justice but it was content to govern within the constraints of the new international consensus which emphasised deregulation, privatisation, financialisation, low tax rates, and liberalisation of the movement of capital, goods and people. The centre-right was not defeated in the battle of ideas—some argue it was never truly challenged.

After 2008, when many of those Third Way centre-left parties suffered such a battering, the old centre-right stood ready to profit—trusted by voters to handle the consequences of the crash and to restore economic health through austerity. But the centre-right has now found it difficult to deliver a convincing economic recovery.

The eurozone crisis in 2010-12 was surmounted, but many of the underlying problems of trying to run a monetary union without a political union and a fiscal union remain; living standards are stagnant, and unemployment, particularly among the young, has been high. Only in 2017-18 did the eurozone return to economic growth, but this remains fragile and has as yet done little to offset the big squeeze of recent years.

Much more than in the 1980s and 1990s, when the fashionable assumption was that everyone would benefit from an expanding economy, there is more anxiety about the unequal spread of incomes and ownership today, and nagging doubts about whether those at the bottom of the heap will actually share in any restored growth.

A still bigger challenge for the centre-right than economics has proved to be immigration. Even a slow-growing European economy has been a magnet for economic migrants and asylum seekers. The numbers seeking to enter the EU has fuelled the growth of populist nationalist parties in many places, and has aided the election of nationalist governments in Hungary and Poland. Established parties of the centre-right and centre-left held the line against the populist nationalists in western Europe, but this changed in 2018 when Lega Nord and the Five Star Movement between them won a majority of the seats in the Italian parliament.

Their newly-formed coalition government now has the potential to upend the nation’s constitutional order. Even in Germany, the hegemony of the ruling CDU has been challenged by the rise of the AfD which began as a Eurosceptic party but has now made immigration its major issue. As for France, while centrist politics may appear to be in the ascendancy with the election of Macron over Marine Le Pen, the old centre-right—in the guise of François Fillon—failed to reach the second round of the presidential election for the first time since the founding of the Fifth Republic.

The nationalist threat

Is there any longer a viable socially liberal, internationalist centre-right formula for government? The strength of the European centre-right parties in the past was that they combined a commitment to international co-operation through Nato and the EU with a domestic politics based on the promise they could secure prosperity, keep citizens safe, and to nurture those traditional social values and shared identity on which national solidarity rested.They addressed the concerns of voters on all six of what psychologist Jonathan Haidt has defined as the moral foundations of politics: care, fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority and sanctity. This made them formidable opponents to the centre-left, who often struggled to challenge them on anything other than the “care” and “fairness” dimensions.

Today, however, the centre-right confronts populist nationalists, who argue that “establishment elites” of the left and the right alike are in hock to international institutions and alliances, which leave them unable and unwilling to control borders and restore prosperity.

At least where “native” citizens are concerned, the populists deploy the old social democrat charge that the centre-right establishment is lacking in care and fairness. But they also attack it in areas of its traditional strength—for a lack of loyalty to the nation, and a lack of will to defend what is sacred about it against the vicissitudes of international commerce and migration. At a time when the authority of Europe’s centre-right is also challenged by its failure to achieve more than an anaemic recovery then, on the Haidt schema of values, the centre-right is left only with “liberty” as its calling card, and libertarianism has on its own not often been a winning electoral formula.

Populist nationalists promise a return to hard borders, national currencies, protectionist economies and in many cases the restoration of social conservatism. This is not just a European phenomenon. The populist nationalists secured their biggest breakthrough with the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

As he dallies with trade wars, he undermines one crucial element of the “free economy” agenda which Ronald Reagan, like Thatcher, married to the muscular state. As Trump’s grip on the Republican Party tightens, it is becoming increasingly difficult to see how the familiar alliance it achieved between the modernising forces of business and social tradition can be put back together again.

Economic protection has not yet spread from the populists to the mainstream right in Europe, but—with speculation about trade war in the air—who can be sure that this will not happen? If it does, then the old centre-right parties of Europe could be in for the sort of convulsions that are already juddering through the US political establishment.

Steve Bannon, one of the major players in Trump’s victory, has spoken of his hopes for an international Tea Party, uniting the populist movement in the US with parties like the Front National, Lega Nord and AfD in Europe. In Bannon’s Manichean worldview the political, cultural and corporate elites, which established the post-national order and continue to govern it, are the enemy. This insurgency against the elites feeds on resentment of their power and wealth and their perceived disdain for national identities and national interests.

The great difficulty the centre-right parties face today in countering this attack is that the current economic impasse is unprecedented in modern times. There have been ups and downs of the economic cycle and sometimes more prolonged periods of painful adjustment, such as the 1970s in Britain and Italy. But recessions were always short-lived, on average 18 months, and recoveries mostly vigorous and sustained.

Centre-right parties always used to think they had the keys to prosperity. The growing number of citizens who had a stake in the economy through home ownership, pensions and savings provided a natural pool of support for the centre-right, easily scared by centre-left proposals to raise taxes or increase borrowing. The hope that each generation could do better than its parents was, for many voters, reason enough to stick with the centre-right custodians of the established economic order.

But now, post-crisis, in Britain and many other countries too, sky-high house prices, stagnant pay and insecure work patterns are making that old story of generational progress a less plausible sell. More immediately, there is exhaustion in the face of retrenching governments that have for so long been promising a more prosperous tomorrow, which never seems to arrive.

European voters have mostly not turned back to the centre-left as they used to when the pendulum swung, but instead to populist nationalists—not necessarily believing that the populist nationalists can improve their situation, but as a protest against an establishment that is no longer delivering on what it promised. Can this slide towards populist nationalism be resisted? The forces of economic and cultural resentment are powerful. Until the economic impasse is decisively shrugged off, the balance is likely to tilt further away from the establishment parties.

The centre-right urgently needs a strategy to resist further loss of support. The most favoured option thus far has been to move on to the ground already occupied by the populists: talking tough on immigration, law and order, and traditional values, while offering at the same time somehow—through means which are often unclear—to protect jobs and living standards.

Some in the centre-right parties will glance at Hungary, Poland, Turkey and—perhaps—the United States, and see the pioneers of a newly “illiberal democracy” reaping rewards after disdaining international institutions, democratic norms and constitutional safeguards. Increasingly more concerned with the threat from populist nationalists on their right than from social democrats on their left, once mainstream parties are increasingly ready to step away from the old centre ground.

This is a difficult strategy to get right because the populist nationalists are able to outbid the mainstream party: a promise to reduce immigration sounds rather tame compared to a call to close the borders.

Another problem is that moving on to the ground of the nationalists, particularly on immigration and economic protection, risks upsetting the liberal wing of the old centre-right coalition. Its parties used to thrive by appealing to a wide spread of voters while also persuading most right-wing activists too that one big centre-right party is the best way to secure office and implement conservative policies. The activists have accepted that debates about priorities and purposes are best resolved internally. But this only works if there are means to secure compromises between the different factions, and if each faction feels itself sufficiently represented and respected within the party.

If centre-right parties move too far towards those voters attracted by the strident messages of the populist nationalists, they may fracture their internal coalition. In the UK context, for example, the part of the winning 1980s coalition that was more concerned with the “free economy” half of the Thatcherite programme could begin to balk at the Tories if they became overwhelmingly fixated instead on the strong national state.

The crumbling bulwark

Brexit might seem to make Britain a unique case at the moment, but in fact the many problems it poses can be seen as a particular instance of the dilemmas that the European centre-right is grappling with everywhere. The Leave vote remains a crushing blow to moderate, outward-looking Conservatism in Britain: 57 per cent of the voters who gave David Cameron his majority in 2015 turned round a year later, ignored the advice that he and much of the rest of establishment gave, and voted to pull Britain out of the bloc that had been a cornerstone of its economic and foreign policy for two generations.Although Cameron’s successor would have the satisfaction of watching Ukip crumble, Theresa May continued to govern as if she faced another imminent populist threat. She spoke not only about the economic grievances of the “just about managing,” but also charges global elites who work across national borders with being “citizens of nowhere.”

More concretely, although she voted “Remain” herself, on moving into No 10 she felt obliged to give a maximalist interpretation of the “Brexit mandate,” even though this gives her all manner of difficulties in a parliament where there was never any majority for a “hard” exit, and especially not since she squandered Conservative seats in an early election. The parliamentary mandate and the referendum mandate are now in conflict, and it is difficult to envisage a happy resolution.

No matter that May understands that if she does pull off a hard Brexit, there could be severe economic damage that will threaten British prosperity and disillusion those many core Conservative supporters who have always put the economy first.

She continues to fear—perhaps even more—that if she does not deliver a hard Brexit, taking back control of laws, borders and money, the legitimacy of British government will be undermined, and a successor to Ukip will arise to punish the Conservatives. And in the defensive crouch they adopt in the face of the populist-nationalist agenda here, the post-Brexit Tories are in sync with those centre-right forces on the continent who—until they marched out of the European People’s Party in a nationalist huff a few years ago—the Conservatives used to regard as their sister parties.

Across Europe, a chill is being felt by the centre-right parties that used to be the great bulwark of the international liberal order, against a return to the authoritarian nationalisms of the past. It is not just the fate of individual leaders or even individual parties that will be determined, but the ability of those parties to continue with their historic role—in securing constitutional order at home, and honouring their nation’s traditional alliances and commitments abroad.

“The west” as we know it was a creation of the centre-right parties, and the effects for the west could be fateful if they do not prove able to master the grave challenges that confront them.