Seventh October, 1989. The German Democratic Republic is celebrating 40 years of its existence. A grand military parade has been in progress on Unter den Linden, one of Berlin’s main arteries. Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev is on the grandstand alongside the GDR’s sclerotic leadership. With the last formation of soldiers duly saluted, Gorbachev ignores the official script and delivers a carefully calibrated warning to GDR leader Erich Honecker: “life punishes those who come too late.” The Soviet champion of perestroika—economic liberalisation—presents it as a clear choice: reform, or face oblivion. His immediate target may have been the GDR’s rigid communist orthodoxy, but the reformist leader knows that his words will encourage the more restive members of the communist bloc to press for greater liberalisation.

Soon all of East Germany hears the message, and before long it spreads across the Soviet Empire and beyond, to the western world. A spark is lit. Within weeks the Iron Curtain crashes, the Soviet Empire is in freefall, the Cold War is relegated to history and a divided Europe is apparently well on the way to becoming whole again.

I was in Berlin to witness Gorbachev’s historic intervention. I was there again a few weeks later when East Germans came pouring through the monstrous wall to embrace their fellow Germans in the west, and I was in the city a year later when the now-unified Berlin became the capital once more of a unified Germany. And this time it was a Germany set to become a beacon for democracy, in a Europe of nation states at the heart of a peaceful and prosperous world order.

During those historic moments, I shared in the general optimism. I looked back on the horrors of Hitler, the Holocaust, the Second World War and the Cold War, and though experience had taught me that the future would create new fissures, caught up as I was in the euphoria of the time I felt confident that peaceful co-existence in Europe was possible. Of course Vladimir Putin was not yet on the public horizon, and in 1989 most of us allowed ourselves to hope that future Russian leaders would be like Gorbachev—a man with whom, in Thatcher’s famous words, “we could do business.”

In retrospect: big mistake. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has undermined more than 30 years of (intermittent, often flawed) effort—since the breach of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Warsaw Pact—to develop a solid, co-operative relationship with Russia. A new and dangerously impenetrable Iron Curtain, shifted eastwards because of Nato’s expansion, has come sliding out of storage.

I was born in Vienna in 1929 to secular Jewish middle-class parents at a time when Hitler, already infected with the poison of antisemitism, was lumbering up the political ladder to take over the Weimar Republic. In 1939, with Hitler in full power in Greater Germany, including Austria, I became a Kindertransport child. Uprooted from my home to settle in Britain, I was arguably a minor victim of his urge to eradicate Europe’s Jews.

Growing up during the war, my backstory, together with deepening knowledge of the Holocaust, probably conditioned me to greater political awareness than the average teenager. That was a bonus when I started working as a journalist and became the Guardian’s United Nations correspondent in the early 1960s. The Cold War was then at its deepest, most vituperative—and most dangerous. I was in New York during the Cuban Missile Crisis and can vividly remember wondering whether I would still be alive from one day to the next. Recalling America’s determination to prevent the stationing of Soviet missiles in Cuba, so near to its mainland, I can see why Russia now wants Ukraine to stay out of Nato—though its attempts to secure such a commitment by military force are unforgiveable. During my posting at the UN, the Non-Aligned Movement—with its influential membership of nations across the world who sought independence from the two main power blocs and lobbied for nuclear disarmament—briefly also reached a peak. Had it been able to maintain its strength, joining it could perhaps have been the safest status for Ukraine, and possibly also for the smaller Baltic countries. Unrealistic? In any case, it’s far too late now to think of such solutions.

I switched continents in the late 1960s, and back in Europe I began to follow east-west affairs not just at the level of diplomacy but also at the grassroots. I was describing a Cold War in which mutual assured destruction—“mad”—and “containment” were the watchwords of western policy, and I cheered as the tensions slowly (and with numerous setbacks) dissipated, giving way to the concept of peaceful co-existence.

Then, in 1968, I watched the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact members as they invaded Czechoslovakia and crushed the Prague Spring, to show there would be no escape from Moscow’s stranglehold. Over the following years, I spent time in Bulgaria, Romania and controversy-loving Poland, and found little sign of significant dissent from communist orthodoxy. An “audience” with Romania’s pretentious president Nicolae Ceauescu exposed the shallowness of his claims to be conducting his foreign policy free from Soviet domination.

The first glimmer of diplomatic movement came in 1972. I was in Dipoli, a conference centre near Helsinki, for the launch of the ponderously named Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe—CSCE. Participants included virtually every European country as well as the United States and Canada. The USSR had been pushing for this while Nato countries had resisted, calculating that Moscow saw CSCE as a device to solidify the Iron Curtain and secure formal recognition of the division of Europe and the borders of the Soviet satellites. Among the major western powers, only France was keen to test the potential of this new diplomatic forum, which speculated that it could open the way to better east-west relations. The CSCE was negotiated over three years, culminating in the 1975 Helsinki accords.

Europe’s dangerous east-west division is back with a vengeance. But the indiscriminate destruction in Ukraine has taken Russia back even further

It has become customary among many historians to hold up the Helsinki accords as the symbol of a Europe of democratic sovereign states, with the fateful 1945 Yalta summit at the opposite end of the spectrum as the symbol of Europe’s east-west divide. In reality, the Helsinki accords in themselves did not end the division of Europe into rival camps. They left Germany divided and the Warsaw Pact in place. The point of the accords was that they contained the key to far-reaching change further down the line. The western powers had managed to insert a “basket” of undertakings in them to respect human rights, like freedom of expression and travel across borders. It was a brew to encourage and give strength to dissent. It helped to convince Gorbachev of the need for glasnost—of greater transparency and openness. Helsinki was not an end point; the CSCE process towards a Europe of free democratic nations—the USSR included—was kept alive with periodic meetings between the signatory states.

The progression from Cold War to peaceful co-existence owes a great debt to the Helsinki accords. As a motor for change, their impact was slow to make itself felt. It differed from country to country in the communist bloc. I witnessed it at its most significant in Poland, in November 1978. Karol Wojtya had just become Pope John Paul II and I was in Poland to cover the Pope’s first visit to his home country. His presence triggered an explosion of support for the Church. From Warsaw to Kraków and way stations between, it was staggering to see the hundreds of thousands who turned up to pray, listen and cheer the Pope as he exhorted them to fight for the Church, for liberty of belief and above all to remain true to their faith. It was a call to arms against communism. The Polish Catholic hierarchy, which had long collaborated with the communist regime, had no choice but to rally behind their militant figurehead. The Polish regime itself was paralysed in the face of a verbal onslaught from the Pope’s battalions. It was the beginning of the end of the Cold War. One of Poland’s senior politicians murmured: “this is irreversible. It is the end of the Iron Curtain.”

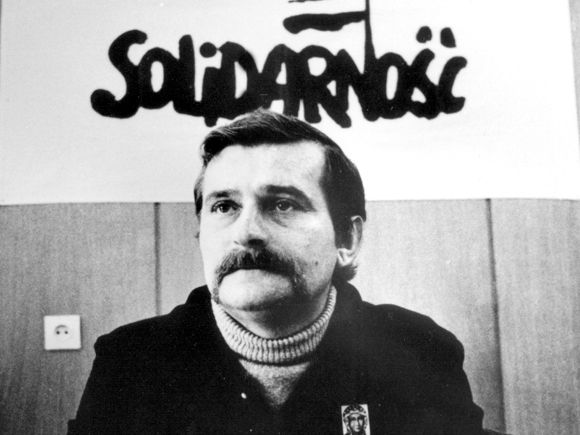

Poland became the vanguard of east and central Europe’s quest for liberation from a Soviet communist overlord. It was no coincidence. Poland’s history, size, the deep implant of the Church and a significant class of intellectuals combined to make it fertile ground for change. Even so, it would take another two years for Lech Wałęsa, still then an unknown shipyard worker, to emerge into the limelight as a determined trade unionist who led a strike in the Gdask shipyards. This created the dynamic for labour and intellectuals to come together in a campaign for greater freedom and better work conditions. Wałęsa and several others suffered prison sentences.

By 1981 protest, far from being quelled, was becoming more widespread. I had been spending much time in Poland and shared in the widespread speculation that Leonid Brezhnev was on the verge of intervention to bring Poland back to heel, restoring the country as Moscow’s orthodox communist acolyte. Partly to deter the Russians, Poland’s premier Wojciech Jaruzelski decided to deal with this challenge to his power by imposing martial law. It later became known that the Soviet military, already being bloodied in Afghanistan, had cautioned against opening another front, and that the Politburo in Moscow accepted this advice. Given this precedent, I wonder whether Putin listened to his military before ordering the invasion of Ukraine?

Back in 1981, the Polish leadership soon learned that martial law could only serve as a temporary brake on protest. After 18 months it was lifted, and a softer form of communism spluttered on. Early in 1989, around six months before the breach of the Berlin Wall, Poland held its first genuinely free general election. It was an unmistakable message to Gorbachev’s Kremlin. Poland’s shift towards democracy signalled the demise of the Soviet Union’s communist bloc. Gorbachev accepted what was happening. Putin was still a hidden KGB operator, but as we now know he never reconciled himself to the loss of the empire.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany arguably became inevitable. Even Gorbachev recognised the uncomfortable truth. But the USSR assumed that reunification would be a drawn-out process, lasting years. Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze thought so too and personally assured me of it at the time. But the so-called “two plus four” negotiations between the two German states and the US, UK, USSR and France were completed within a year and, with the blessing of the USSR as well as the west, a united Germany assumed its new identity in October 1990. An era of peaceful co-existence was launched.

But given the new-found goodwill across the old east-west faultlines, a great opportunity was missed to negotiate a future European security architecture. I was at the Council of Europe meeting where Gorbachev outlined tentative proposals for a “common European home,” built on economic and strategic co-operation across ideological divides and with “the sovereign right of each people to choose their own social system.” There was even a tentative suggestion for the Soviet Union to join Nato. But none of this was followed up.

Crucially, the size of Nato’s future sphere was left ambiguous. While agreement had been reached that a united Germany would be a Nato member, there were no decisions on the possible extension of membership. At the time of the two plus four agreement, US secretary of state James Baker told Gorbachev that Nato would not expand “one inch to the east,” though his exact meaning is the subject of some debate. Germany’s chancellor Helmut Kohl and UK prime minister John Major offered similar assurances. However, US president George HW Bush, opposed to the idea of giving any such guarantees, rowed them back. Nothing was put down in formal writing.

For the western powers, that was the end of it. Not so for the Russians—though at the time Gorbachev may have been too preoccupied with domestic issues to pay much attention. Putin has always treated Nato’s expansion to the east as a betrayal of supposedly firm commitments and as a threat to Russia’s vital security interests. He uses this argument as part of his justification for the war in Ukraine.

That war has destroyed the promise of 1989 and the admittedly patchy gains of peaceful co-existence. Having closely followed east-west relations for decades, it was deeply dispiriting to see how the high hopes at the end of the Cold War dissipated. Lessons learned were ignored. Opportunities to secure lasting gains were missed. The west’s attention on Russia waxed and waned.

Now Europe’s dangerous east-west division is back with a vengeance. But the indiscriminate destruction and butchery of civilians in Ukraine has taken Russia back further, to the kind of horror seen when I was a child. The Nazis established concentration camps to implement the mass killing of Jews and other undesirables. Putin so far at least has no gas chambers. But he uses his soldiers and his missiles to do the killing, all with the aim of exterminating Ukrainian identity. Putin’s intent is not far from genocide, and to my mind there is an inescapable parallel with Hitler and the Holocaust.

The original update to this piece recorded Hella Pick's age at death as 94. In fact, she was 96 when she passed away on 4th April 2024 and the text has been amended to reflect this