“There are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks where decades happen,” said Lenin of revolutionary change. If you look across the Irish Sea, decades may be happening in these weeks leading up to May’s elections for the Northern Ireland Assembly. If Sinn Féin come top, in line with the polls, the UK province’s new first minister will be Michelle O’Neill, deputy leader of the party once umbilically tied to the republican terrorist IRA.

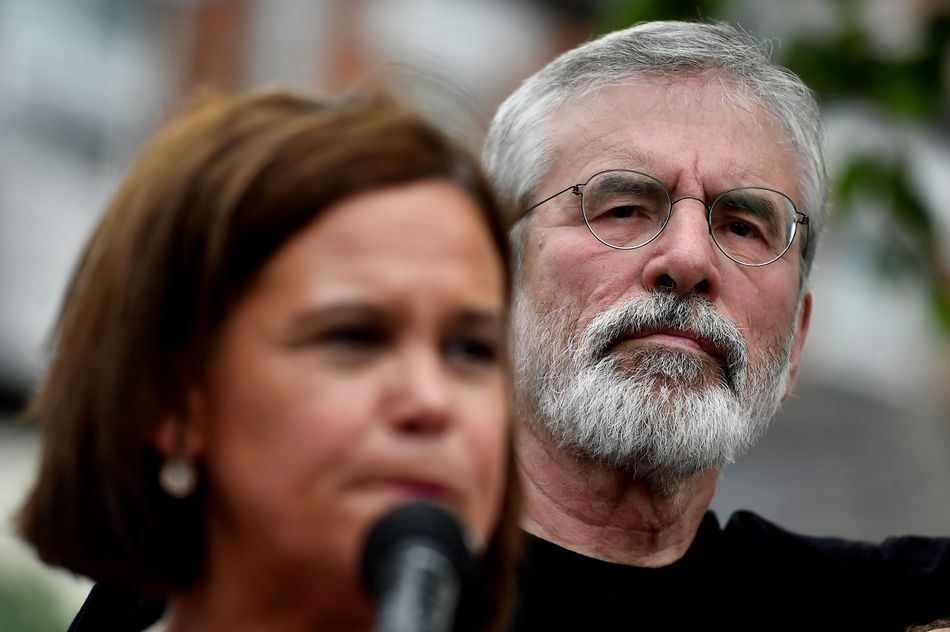

A still bigger earthquake could follow within three years if Mary Lou McDonald, Gerry Adams’s handpicked successor as Sinn Féin leader four years ago, turns her current 15-point poll lead into an election victory south of the border. This would make her Sinn Féin’s first taoiseach (prime minister), indeed its very first minister, since the creation of the Republic of Ireland a century ago. The party will have united the whole of Ireland behind its leadership in one of the most extraordinary feats of modern electoral politics.

Sinn Féin and Brexit are driving this revolution in double harness. Brexit has undermined Northern Ireland’s constitutional and economic position within the UK, while at the same time taking a hatchet to the complex structure of co-operation and interdependence between the UK and Ireland dating back to their joint EU accession in 1973. The immediate casualty is the chauvinistically unionist DUP, the top party in Northern Ireland for the last 14 years, which is imploding. The DUP has had three leaders in the last year alone, after indulgently allowing its cultural antipathy to Irish nationalism to trump pragmatism and trap it into backing first Brexit, then Boris Johnson’s hard Brexit, in defiance of a large pro-EU majority in the province.

To keep an open border with the south, hard Brexit—taking Britain out of the EU’s single market and customs union—necessitated the Northern Ireland protocol. The effect of the protocol is to keep the whole of Ireland within the EU. In less than a year, this has radically detached the province’s economy from Great Britain and re-aligned it with the Republic. Political unionism is now in deep trauma and increasingly adrift from cultural unionism.

“As we all know, in practice, Ireland allied itself with the United Kingdom on most of the everyday issues” before Brexit, Leo Varadkar, Ireland’s tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and former taoiseach told a conference in Dublin last year. No more. A united Ireland is now possible “in my lifetime,” he has said, and this from the party leader in Ireland who used to routinely condemn Sinn Féin for saying precisely that. The biggest threat to power-sharing in the north, and to Ireland’s entire economy north and south, has long since ceased to be the IRA; it is now, incredibly, the British state itself, whose behaviour is exacerbating historic antipathies between nationalists and unionists in the north, and between the north and south at large.

Sinn Féin is surging because Brexit struck just as the party was being successfully rebranded by McDonald and O’Neill, who took over the leadership in 2018, two decades after the IRA abandoned the “armed struggle” and Sinn Féin entered the new Northern Ireland assembly. Soft-focus “Mary Lou and Michelle” represented a dramatic rupture with hardline “Adams and McGuinness” and their old Belfast/IRA “Shinners.” In the south, Sinn Féin has rocketed from virtual non-existence 25 years ago—polling just 2 per cent in the 1997 election for the Daíl (Irish parliament)—to 10 per cent in 2011 and 25 per cent in 2020. The latest poll puts Sinn Féin at 35 per cent, by far its highest rating ever. In the north, the party has nearly trebled its support, from 10 per cent in 1992 to 24 per cent in 2010 and just shy of 30 per cent in 2019.

North and South, an ancien régime is collapsing and a new order in gestation

Mary Lou McDonald could not be more different from Gerry Adams and still be Irish. A middle-class, privately educated, graduate Dubliner with a husband and two young children, she didn’t join Sinn Féin until she was 30, when she defected from Fianna Fáil, traditionally one of Ireland’s two main parties. “I couldn’t believe it when I first saw Mary Lou on telly back in 2004, as a new MEP,” says Shane Ross, her biographer and a former minister under Varadkar. “‘What the hell is this?’ I thought. Articulate, well-dressed, emollient, she doesn’t look or sound like a Shinner. She is the best performer in the Daíl and on the media. She is good at opposition, creating merry hell in minutes in the Daíl without appearing extreme or inept. But she doesn’t want to stay there. She wants power, she appears to want it more than the men she is facing, and she senses that it is hers if she can take the centre-ground.”

North and south, an ancien régime is collapsing and a new order in gestation. It is about a transformational moment—the long-run effect of EU membership, peace, secularisation and now Brexit combined—as much as the actors on the stage. “Mary Lou is a professional politician with a bit of flair: what makes her so potentially significant is where she is placed at this juncture in history,” says Ross.

Ireland’s culture and politics remain visibly shaped by the long struggle against English and Scottish imperialism and the civil wars that followed the independence of the south and the partition of the north a century ago. Those lesions only finally healed with the Good Friday agreement of 1998, which ended the war between the IRA and the British state. It took Ireland most of the 20th century to recover from the double catastrophe of the horrific famine of the 1840s and ensuing mass emigration, followed by the close-run failure of William Gladstone, Victorian Britain’s greatest Liberal leader, to establish a self-governing Ireland with a single parliament in Dublin within a reconstituted federal United Kingdom. Two attempts to carry this legislation were fatefully blocked by the Tories at Westminster in 1886 and 1893; just two decades later, amid the First World War, came the Easter Rising.

McDonald proclaims a new dawn while refusing to repudiate the armed struggle and its partisans

After this almost unmitigated strife, 21st-century Ireland is on the up. Its population, a good prosperity index, has increased by nearly half in the last century—nearly twice as much as England’s proportionally. Over the previous famine-stricken 19th century, it declined by a third while England’s quadrupled. Even the centuries of emigration have come to good effect, in the form of a huge and influential diaspora. One especially proud descendant of Irish emigrants is Joe Biden, who loves to quote Seamus Heaney in his speeches: “History says, Don’t hope/On this side of the grave./But then, once in a lifetime/The longed-for tidal wave/Of justice can rise up/And hope and history rhyme.” Biden’s White House is virtually a Sinn Féin headquarters.

Seizing the moment, McDonald focuses on mainstream concerns like housing and health, campaigning in a fresh style akin to New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern. Ireland’s problems are blamed on “out of touch” Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, both centre-right parties that came out of opposing factions in the post-independence civil war. She talks like a conventional social democrat, but in a country with a weak progressive tradition it sounds daring, as if it were making up for lost time. Her central policy—apart from Irish unification—could not be more ironic: for Ireland to move away from its highly inequitable two-tier public and private healthcare system and create a tax-funded National Health Service like Britain’s.

The 2020 general election was a huge boon. Sinn Féin narrowly topped the poll, surging in the campaign itself with a near-equal three-way split of seats between Sinn Féin, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. The two establishment parties promptly formed an anti-Sinn Féin coalition without even attempting to engage with McDonald, making her leader of the opposition and their sole credible rival. This looks to be career-ending for the uninspiring Micheál Martin, leader of Fianna Fáil, once the fiefdom of Ireland’s hardline Catholic founding father Éamon de Valera. Under the coalition pact, Martin is taoiseach until the end of this year, when he hands over to Leo Varadkar, the leader of Fine Gael. Varadkar will face McDonald in the next election, which is due by February 2025 at the latest.

In a ground-shifting new year interview, Martin said that Fianna Fáil would negotiate with Sinn Féin if a similar situation recurs after the next election. But in that event, the consequence for Fianna Fáil is more likely to be a rout than a partnership.

Varadkar, whose father is an Indian immigrant doctor and his mother a nurse from County Waterford, became taoiseach for the first time in 2017 at the age of just 38 (he is ten years younger than McDonald). The first serving Irish minister to come out as gay, he represents as sharp a break from Ireland’s Catholic past as does McDonald from its terrorist past. Touring Ireland three years ago during Pope Francis’s papal visit, which attracted only a fraction of the crowds of John Paul II’s triumphal visit of 1979, I watched—in a bar in Waterford—Varadkar’s pitch-perfect speech of welcome to the pontiff, politely yet boldly proclaiming a post-Catholic Ireland. “He’s got it, that boy,” said the guy next to me, nursing a Guinness. Ireland’s destiny may turn on the interplay between McDonald and Varadkar over the next decade, provided the latter survives controversy. (Varadkar is under pressure over the leaking of a confidential draft government contract with one medical organisation to a friend of a rival one, which is further boosting Sinn Féin in the short term.)

“Things were bad enough when these two parties pretended to oppose each other. But by God things have gone to the dogs since the boys clubbed together,” McDonald jibed cuttingly of the governing coalition at Sinn Féin’s ard fheis (conference) in Dublin in October. That riff has a lot longer to play.

Talking to leaders and delegates at the ard fheis, I was struck by the disciplined pragmatism and thirst for power. It was like New Labour in 1997. The fateful question is whether McDonald’s Sinn Féin not only looks new, but is new.

McDonald treads the line post-conflict nationalist leaders often do, proclaiming a new dawn while refusing to repudiate the previous armed struggle and its partisans. She paid tribute to provisional IRA volunteer Bobby Storey by attending a classic “provo” funeral in Belfast last year, in apparent defiance of Covid-19 regulations. But her narrative is relentlessly of the future, not the past. Her polished autocue speech at the ard fheis opened with lines on “Palestinian freedom” and “an end to the brutal blockade of Cuba,” but within moments she was on to the “housing crisis, rip-off rents, overcrowded hospitals, record waiting lists and a crushing cost of living.”

On these bread-and-butter issues, McDonald has stolen the populist mantle from Fianna Fáil, a party whose everyman appeal helped keep it in power for 63 of the last 90 years. “Fianna Fáil hasn’t been doing serious welfare politics in local communities since the 1990s; they’ve been steadily losing it to Sinn Féin,” says Ciarán Cuffe, a long-serving Green politician and now an MEP.

Sinn Féin isn’t hegemonic in either the new left in the south or the nationalist community in the north. The Republic’s single transferable vote electoral system—proportional in constituencies of three to five members, obliging candidates to run against party colleagues—encourages splinters and independents. Sinn Féin lost a by-election in Dublin last July to a prominent reproductive rights campaigner standing for the Irish Labour Party, while in the north the Social Democratic and Labour Party—led by the dynamic Colum Eastwood in the shadow of the fêted John Hume, who died a year ago—remains a force. But Sinn Féin is polling consistently way ahead of its rivals in the north and south and boasts the best electoral machine across the whole island.

In a significant symbol of reassurance, the substance of October’s ard fheis was McDonald’s announcement that a Sinn Féin government would end its longstanding opposition to juryless trials for serious criminal offences, including those in the Special Criminal Court, infamous for locking up IRA terrorists. Delegates endorsed the change through gritted teeth, in order to demonstrate that a Sinn Féin government would be tough on security and organised crime, despite its infamous past associations.

While debate advances on a united Ireland, there is a void of ideas on the future of Northern Ireland

Abiding concerns about Sinn Féin and security won’t dissipate until McDonald is able to allay them in government, provided she gets there. Since “you will never see another IRA man in the Special Criminal Court” anyway, Sinn Féin’s new stance “is not all that it seems,” says Michael McDowell, an independent Irish senator sceptical of the U-turn. But McDonald looks tough enough to face down the hardliners and prove her party has changed. There are parallels with Fianna Fáil, on the losing side of the 1920s civil war and an insurgent electoral force in the early 1930s, which was similarly distrusted on security until de Valera took office and kept the existing apparatus in place.

“It is stomach-churning hearing Mary Lou going on about good government and new politics when the IRA is understood to still hold £20m from the Northern Bank robbery in Belfast [in 2004], said to be for IRA pensions, and she’s reluctant to admit that Adams was a member of the IRA,” says a senior Fine Gael adviser who wished to remain anonymous.

“The whiff of cordite is still there,” says a Green Party leader on the same basis. “It’s still pretty grim. When I was a Dublin city councillor only six years ago, an apparently respectable Sinn Féin councillor stood down. We all wished him well. Later he was jailed for involvement in paramilitary activities including waterboarding.”

Others like him remain, and the Belfast-based IRA army council is thought still to exist. One parliamentarian I spoke to said he was haunted by having had an office in the Dáil on the same corridor as Martin Ferris, a Sinn Féin member with a string of terror-related convictions as well as reputed former membership of the army council, whose daughter is a radical left figurehead in the party.

My verdict is that Sinn Féin is morphing into a conventional party, but it is still work in progress. A particular concern is that financial corruption, recurrent in Irish politics north and south, could escalate under a Sinn Féin administration. Given the IRA history of illegal and illicit funding during the Troubles, making it almost a state within a state, political opponents are worried what might happen if Sinn Féin gains untrammelled control over the Irish Treasury and the levers of power. “Sinn Féin has more money and property than all of Ireland’s other parties put together, the fruits of decades of American fundraising,” says Shane Coleman, presenter of Ireland’s cross-community Newstalk Breakfast programme. This is partly why its electoral machine is so well-oiled.

Sinn Féin’s whole credibility hangs on McDonald’s personal reputation for being politically clean as well as fresh. No one accuses her of personal association with corruption or terrorism. “She isn’t a revolutionary, let alone a criminal; she’s a popular leftist,” says Ross, who served with her on committees in the Daíl after 2011. “At a personal level she is good fun, amusing and pleasant. You can’t find people who say bad things about her personally.”

“If Sinn Féin go into government, it will be a party of BAs and MAs, not PoWs,” says former Fianna Fáil ministerial adviser and political commentator Derek Mooney. An English literature graduate of Trinity College Dublin, McDonald went on to complete a masters in European integration at Limerick University and then studied industrial relations at Dublin City University, the venue for October’s ard fheis. Her finance spokesman, Pearse Doherty, spouts facts and figures while Eoin Ó Broin, ex-University of East London, makes the weather on urban Ireland’s housing crisis, which is as bad as or worse than England’s. His book Home: Why Public Housing is the Answer was a surprise Irish bestseller, eviscerating the “pro-developer” governing parties who have overseen Ireland’s sky-high rents and lack of affordable housing.

Sinn Féin has seven MPs from the north in Westminster, where unbeknown to most they have offices and staff and engage closely in politics, although not taking their seats in the chamber. One of them, Chris Hazzard, started a PhD on why Ireland never set up a Beveridge-style welfare state. Later, in 2017, he became the youngest member of the Northern Ireland assembly for South Down, Enoch Powell’s old parliamentary district. He speaks encyclopaedically of the constructive relationship between Attlee’s postwar government and Basil Brookeborough, unionist prime minister of Northern Ireland from the 1940s to the 1960s, and of de Valera’s promotion of the Celtic pastoral ideal and Catholic hierarchy in the south over the same period, both solidifying partition.

As a UK member of the Council of Europe, the pan-European human rights assembly made up of members of national parliaments, I was impressed at its meeting last September by Paul Gavan, an Irish rapporteur, who made a host of practical suggestions for resolving the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and engaged sensitively with delegates from both countries in a fraught session. Only afterwards did I learn that he is a Sinn Féin member of the Irish senate.

Underpinning Sinn Féin’s new appeal and credibility are two major ideological shifts that predate the latest one on security. The party has come to terms with membership of the European Union, after campaigning against virtually every EU treaty of the last 30 years, and it is also now firmly liberal on social issues, totally repudiating the Catholic hierarchy.

However, the striking absence is of any Sinn Féin plan for economic growth and wealth creation. The word “business” was only mentioned at the ard fheis as a term of abuse, and there was barely any reference to Ireland’s inadequate higher education system and dilapidated national infrastructure. Dublin recruited a fair group of digital companies during the tech boom, but it lacks a single university in the global top 100 (Trinity College Dublin long ago dropped out of that league). Its inter-city transport network is deplorable—it takes two hours to travel the 100 miles from Dublin to Belfast on a train that only runs every two hours—and the 2008-2009 crisis exposed clientelist corruption in Ireland’s financial sector of Greek and Sicilian proportions. The field is wide open for a party pushing a bold Irish growth strategy spanning north and south. McDonald shows no hint of recognising this and strikes largely “old Labour” high tax and regulatory poses, alarming to many of Ireland’s business leaders. It may be even worse than that. One senior international banker of equable disposition told me, again anonymously: “banks are reluctant to repossess farms in Ireland for fear of retaliation, and there are regular (although less frequent) stories of kidnapping and torture of business leaders who have crossed the wrong people. We run training on what to do if kidnapped, which I have never had to do in my previous banks.”

How would a Sinn Féin government proceed on Irish unity? Here a fascinating pas de deux is developing between McDonald and Varadkar, with the Sinn Féin leader seeking to lower expectations while Varadkar raises them. Both are converging on a newly imagined centre ground, where a united Ireland might now just be a matter of a date sometime between 2030 and 2040.

Varadkar’s personification of an open and newly secular Ireland is paying dividends. Polls show him to be the second-most popular politician in the north after Naomi Long, leader of the cross-community Alliance Party, which is shrewdly exploiting the DUP’s implosion in unionist heartlands. Varadkar is reaching out to the north just as McDonald advances in the south.

“If you want a united Ireland, based on unity rather than head counts, now is the time to stop talking about it,” quips the Irish poet Michael O’Loughlin. Everyone knows that unification isn’t about majorities but hearts and minds, and that every step on the road is strewn with boulders, including the first.

At October’s ard fheis, the debate on “a new and united Ireland” came towards the end, after sessions on housing, the environment, rural Ireland, education, and the vote for juryless trials. Even the unity debate featured far more detail on a whole-island national health service than anything else.

When might a referendum on unity, known as a “border poll,” take place in the north? A senior British civil service observer of the Irish scene points out that there were seven years, two general elections and two Scottish parliament elections between Alex Salmond becoming the first SNP first minister in Scotland in 2007 and a Westminster-approved independence referendum in 2014.

Thinking on timescales in Ireland is similar to this on all sides, for the people around McDonald, Varadkar and Long as well as among British officials—though it is unstated publicly, and often even internally because of its sensitivity. A leading Varadkar adviser talks of a border poll “probably in the next 10 years but with big events before then, including ratification of a reformed Northern Ireland protocol by the NI assembly.” He thinks a Sinn Féin government wouldn’t attempt a referendum in its first term, but would instead publish outline options and set up some formal constitutional consultation, “then see where that leads.” A re-elected Varadkar might do exactly the same.

The shape of a united Ireland is equally vague. Significantly, even the title of the debate at the ard fheis qualified a “united” Ireland with the word “new.” The resolution on the issue talked airily of “everyone” having “the opportunity to have their say in shaping this new, shared island,” with “those from a unionist background” having “a valuable contribution to make… their culture and identity will be respected in a united Ireland which will be tolerant, inclusive, multicultural and multiracial.”

The big question is whether a united Ireland would be federal, including devolution in the north. McDonald is notably not closing the door to federalism, which could lead to a continuation of a power-sharing devolved administration in Northern Ireland including a guaranteed executive role for “those from a unionist background.” This goes right back to the famous 1959 statement in an Oxford Union debate by Seán Lemass, de Valera’s successor as taoiseach, that “there will always be a government in Northern Ireland.”

Tellingly, while debate advances in both the north and the south about the shape of a single Irish state, on the unionist side there is a void of ideas on the future of Northern Ireland within Boris Johnson’s Brexit Britain. As Owen Polley, a diehard unionist blogger, puts it exasperatedly: “where are the symposiums and panel discussions exploring how Northern Ireland can play a more integral role in the UK?” Jeffrey Donaldson, the latest DUP leader and a veteran player at Westminster, used to have a reputation for reaching across the aisle; now he looks as though he has withdrawn into the bunker.

In a lecture in Florence three years ago on Ireland and Europe, Irish president Michael D Higgins quoted the injunction of Giovanni Boccaccio in The Decameron, set in that great renaissance city during the Black Death: “If one way does not lead to the desired meaning, take another; if obstacles arise, then still another; until, if your strength holds out, you will find that clear which once looked dark.” It is a good message for the political leaders who seek to reinvent today’s Ireland in the heart of modern Europe. Fatefully, it may fall to Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald to be the arch pragmatist entrusted with such a delicate mission.

Correction: this article initially used an incorrect job description for Derek Mooney. The text has been amended