The British constitution never looked less like itself than in the final months of the UK’s EU membership. In office was a government that constitutionally speaking should not have existed: one that could no longer command a majority in the House of Commons. Fearing parliament would legislate against a no-deal Brexit, the prime minister used the Crown’s prerogative powers to prorogue it for five weeks. This encouraged some opposition MPs to take to the Scottish Court of Session to petition for parliament’s right to reassemble. In September 2019, the Supreme Court ruled the prorogation unlawful, elevating the judiciary to a role it had not hitherto performed: as the ultimate guarantor of the British constitution’s conventions.

For those who saw the Court’s decision as correct and necessary, the bedrock principle at stake was parliamentary sovereignty. For many who had long wanted Britain to leave the EU, their inspiration was that very same principle. Each meant something different by it, but all deployed a caricature of the constitution—missing the awkward reality that the principle of parliamentary sovereignty co-exists in practice with an idea of popular sovereignty, centred on democratic consent to constitutional change. Paradoxically, it took the EU experience to teach British politicians about the British constitution.

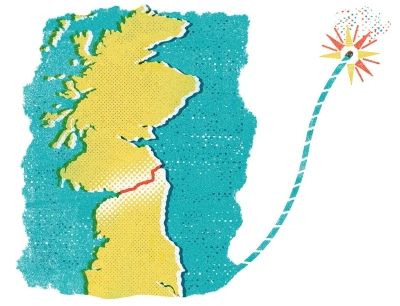

Only now, with this half-century period in our history over, does it become possible to understand how EU membership became a very British story about the perils of ignoring democratic consent. But if this chapter is closed, its lessons remain urgent: the three-century long Anglo-Scottish Union is reaching another crisis point, and we are again reckoning with the demands of consent for the constitutional order.

Original sin

From the beginning, the contrast between the British constitutional tradition and that of the legal order of the European Community that Britain would join in the early 1970s appeared stark. The British constitution was conventionally rendered as the idea that no parliament could bind its successor. This characterisation oversimplified. But the emphasis on parliamentary sovereignty did highlight one undeniable disparity with the EC: the absence of a constitutional court that could set aside the laws parliament passed.

It is inconceivable that the law lords—who then comprised the highest UK court—would have engaged in anything akin to what Perry Anderson, in a recent trio of essays for the London Review of Books, describes as the “brilliant coup” achieved by the European Court of Justice (ECJ). In successive decisions in 1963 and 1964, the ECJ asserted the primacy of Community law over national law, getting the six member states to accept this doctrine as a constraining constitutional principle on their politics. Falling between Britain’s first (1961-1963) and second (1967) unsuccessful applications to join the Community, these rulings heightened the constitutional implications of eventual accession. If the UK were an EC member, there would be new laws with direct effect across the UK authorised by a legislative body other than Westminster.

Aware of the problem, those who drafted the 1972 European Communities Act tried to muddy the waters—by structuring the legislation so that the formal applicability of EC law in the UK was conditional on the British parliament having legislated for it to have effect. Otherwise, the Conservative prime minister Edward Heath and his ministers fell back on obfuscation. “Essential national sovereignty,” they insisted, remained in place, as if Britain retaining a veto in the Council of Ministers was the same as parliament retaining the sole right to legislate. Heath himself was also outright dishonest with the electorate about how he envisaged the Community’s authority developing: as a telegram he sent to his chancellor in March 1973 quietly noted, his government’s “goal” was “economic and monetary union,” something then being pushed by the West German government.

“AV Dicey is seen as the high priest of parliamentary sovereignty. In fact, he defined ‘the true political sovereign’ as ‘the majority of the electorate’”

But from the off, it was an aspect of the British constitution less lauded than parliamentary sovereignty that proved more troublesome for such ambitions. Heath himself had at one point acknowledged that membership would require the “full-hearted consent of the British parliament and people.” Given his manifesto (“our commitment is to negotiate; no more no less”) though, it was a struggle for him to claim a mandate for accession from the 1970 general election. In ultimately deciding that parliamentary assent alone was sufficient to bring about EC entry, Heath committed a constitutional sin by ignoring the issue of the electorate’s consent to a major constitutional change.

The principle that he breached was one forcibly articulated in the writings of AV Dicey, the Victorian constitutional theorist usually invoked as the high priest of parliamentary—not popular—sovereignty. (His most famous lines are about parliament being free to “make or unmake any law whatever.”) Dicey worried that parliament could in principle pass significant constitutional legislation that did not enjoy majority support from the people, and thus thought there was a place for referendums. Certainly, parliamentary sovereignty ensured that parliament had the sole legal authority to legislate however it saw fit. But for Dicey, parliament’s political authority to legislate was limited by the final sovereignty of the people. As he explained in the Laws of England, the constitution’s conventions were there to guarantee that what was decided “in the long run” gave “effect to the will of that power which in modern England is the true political sovereign of the state—the majority of the electorate.”

In his 1890 essay “Ought the referendum to be introduced into England?” Dicey argued that there were two ways to win a mandate for constitutional change: a general election in which the constitutional issue was central to the campaign, or a referendum. Looking at what happened in practice, he saw examples of general elections doing that work: the one in 1831 fought over franchise reform, after which followed the 1832 Reform Act; and the 1868 election fought on disestablishment of the Church of Ireland, after which followed the 1869 Irish Church Act. Such episodes showed the constitution included “the spirit” if not the “form” of a referendum. But given general elections also had to settle the different matter of who is to govern, in some circumstances, he thought, the form might also be required to do the job.

Slow burn

After the EC accession legislation received royal assent, Labour’s Harold Wilson threw the Diceyan argument at Heath, declaiming that “the treaty which he signed, which he now claims as sacrosanct, was signed without one whit of authority from the British people.” This issue caused the first crisis of the UK’s EC membership, one which Heath, taking full advantage of the British constitution, inadvertently precipitated.

The constitutional rupture in 1973 did not change the adversarial form of politics that the old constitution encouraged: with a first-past-the-post electoral system, a tendency to majoritarian single-party governments and power almost wholly concentrated at Westminster, there was less space for coalitions and the emergence of new governments between elections than in other EC states. The stakes were always high: the party that held power had everything but feared losing everything. The resulting culture was one in which oppositions were liable to oppose much of what a government did—which meant that anything, including treaties, could end up in the electoral mix.

“Every time the EU constitutional order changed, the government was potentially vulnerable to opposition demands for a fresh referendum”

Convinced he could exploit what he assumed was Labour’s weakness over a miners’ strike, Heath called an early election in February 1974. But Labour’s promise of a referendum on the EC, allied to Enoch Powell’s break from the Tories to back that position, meant Heath instead opened up an electoral contest about the treaty he had passed. With Labour narrowly winning that election and an autumn re-run, the referendum on EC membership that the constitution had arguably demanded back in 1972 finally took place in 1975.

Although the “Yes” campaign easily triumphed, ongoing consent to EC membership thereafter depended on two related conditions. First, subsequent new European laws could not intrude on electorally salient matters. Second, the EC’s constitutional order needed to appear constant. Otherwise, the question of consent could re-materialise, and a government seeking to ratify a new treaty would be vulnerable to the opposition demanding a fresh referendum.

From the mid 1980s, there were moments that could have threatened these conditions. A new treaty, the Single European Act, arrived in 1986. Although it introduced veto-proof qualified majority voting on single market issues, in opposition the Labour Party of the day showed no interest in the issue and parliament held no debate on a referendum amendment. Meanwhile, in the Factortame case in 1991, the law lords appeared to strike down part of the 1988 Merchant Shipping Act because it violated EC law, thus formally subordinating parliament to British courts and ultimately the ECJ. But the ownership and registration of ships was not an electorally salient matter.

It was only the prospect of European monetary union and the Maastricht treaty, signed in 1992, that eventually blew open the whole issue. The economic issues involved were obviously crucial, and monetary union posed a painful policy dilemma: sterling’s weakness appeared to be both a reason to seek safety on a European monetary lifeboat and a reason to fear the discipline of a single European currency. Most British politicians played for time, and as they did so they ignored the Diceyan problem of popular consent for constitutional change that loomed on the horizon.

For a while, they succeeded in postponing the moment of reckoning. Margaret Thatcher’s apparent desire to fight a general election around her absolute opposition to monetary union generated dread in the upper echelons of the Conservative Party and brought her premiership to an end. Initially, her successor, John Major, looked like he would easily succeed in using parliamentary votes to ratify a treaty that committed Britain to the first two stages of monetary union—and gave any future government an easy formal means of taking the last step, of converting to the emerging euro. Banished to the backbenches, Thatcher attempted a Diceyan crusade against Maastricht, insisting that “anyone who does not consider a referendum necessary must explain how the voice of the people shall be heard.” But Labour showed little interest in joining her: its spring 1992 manifesto neither categorically opposed the single currency nor tied entry to a referendum.

Only after the wreckage of Black Wednesday, when investors forced sterling out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, did the party leaders become seized by electoral anxiety over the future direction of the EU. While other European governments moved to rescue monetary union, British politicians now feared they would pay a price for further subordinating economic policy to the European Central Bank. In this new environment, and now with only a small government majority, ratifying the Maastricht treaty turned into siege parliamentary warfare. Battered by the experience, the Conservatives soon returned to opposition with a newfound Diceyan view about the indispensability of popular consent for further EU treaties. As for what they had already agreed in the Maastricht treaty, both main parties were fast coming to understand that there was no chance they could contemplate joining the euro in the future without promising a referendum, and both were committed to that being a condition by the 1997 election.

Henceforth, the issue of referendums around the EU would be a matter of British electoral politics. Advantaged by the size of his parliamentary majority, Tony Blair rode out the Amsterdam (signed 1997) and Nice (signed 2001) treaties. The 2004 European constitutional treaty proved a very different proposition: all three principal parties fought the 2005 general election with a commitment to subject it to a referendum. Blair was saved from redeeming Labour’s promise only because French and Dutch voters rejected the treaty before a referendum could occur. When the constitutional treaty was eventually repackaged as the Lisbon treaty, and EU governments encouraged each other to avoid referendums on ratification, Gordon Brown was in charge. Fearing the treaty would be rejected, he invented spurious arguments about supposed differences between the treaties to rationalise purely parliamentary ratification.

For the Conservatives, their insistence that Lisbon should have been subject to a referendum was soon complicated by the rising significance of an issue written into a past treaty: internal EU migration. The party went into the 2010 general election with an immigration target that was—in effect—incompatible with established EU law, along with a promise of a referendum on future treaties, a manifesto package that in the course of events pushed an electorally salient issue (free movement) towards the Diceyan issue of democratic consent. Eventually, Cameron found there would be no new treaty on which he could hold a referendum, and so moved on to staging an in/out vote. But his predictable failure to achieve his immigration target would prove a significant liability in his bid retrospectively to secure the missing popular consent for the treaties from Maastricht to Lisbon.

Which “people”?

The 2016 referendum might have settled one question about consent, but it immediately raised another. Whereas back in 1972, Wilson had talked about “the sovereign authority of the British people,” by 2016, the constitution no longer—if it ever did—made “the British people,” or for that matter Westminster, the sovereign authority of the UK Union. And the question of whether the Scottish and Northern Irish people (who had both voted Remain) any longer consented to the Union would press with renewed force because as powers “came home” from Brussels, there would be fundamental questions about where exactly they were to be repatriated to, the answer to which would rework the relationship between devolved and reserved powers in the Union’s internal constitutional order.

For Dicey, consent was majoritarian and Anglo-British: his language openly betrays that he wanted to treat the English people and the British people as synonymous. He pressed his political case for a UK-wide referendum on Home Rule for Ireland precisely because he thought, in effect, that by virtue of size, the English majority should prevail on the structure of the Union.

But the British people are not, and never were, the English writ large. If a general change to the constitution is taken to require consent, any changes to the 1707 Act of Union’s clear constitutional protections for Scotland should likewise require Scottish consent. Even if Dicey did not accept that, this argument can be cast using his very own distinction: parliament may have the legal authority to overturn the 1707 Act of Union, but it clearly lacks the political authority to do so. Indeed, before the end of Dicey’s life, Westminster would explicitly legislate—in 1921—to restrict itself on matters pertaining to the Church of Scotland in acknowledgement of this.

During the years of EU membership, the idea that the “British people” could be constitutionally disaggregated had taken hold—in ways that would have made Dicey despair. In providing for referendums on the governance of Northern Ireland (1973, 1998), Scotland (1979, 1997, 2014) and Wales (1979, 1997, 2011), Westminster explicitly or implicitly acknowledged that the non-English peoples of the United Kingdom were the sovereign authority regarding their participation in the Union. (Devolution brought implications for England too—not least by creating a de facto English government responsible for matters that were devolved elsewhere—but the question about English consent to change was never asked.)

By the 2010s, both the general principle that constitutional change required plebiscitary consent, and the differentiation between the relevant “people” in the Union, had prevailed over any residual notion that the constitution was Westminster’s business. Take the 2010 manifestos. On top of the various UK-wide referendum propositions floated—the alternative vote and Lords reform (Labour); a written constitution and an in/out vote for any new EU treaty that transferred powers from Westminster (the Lib Dems); the Tories’ “referendum lock” on all such treaties—Labour put forward a Welsh plebiscite on devolving more powers, which the Conservatives signalled they wouldn’t oppose. In the event, the 2010-2015 parliament witnessed the Welsh vote on powers, and—unanticipated at its start—a Scottish vote on independence, as well as a UK-wide referendum on the alternative vote. A consensus about the need for popular consent on constitutional change appeared to have formed. At least in part this included Europe: while Labour did not match Cameron’s immediate referendum commitment in its 2015 manifesto, it did promise that any new treaty would bring an in/out plebiscite.

And yet—when it came—the EU referendum let loose a sustained attack on the very idea that popular sovereignty had any part in the British constitution. Some MPs reimagined parliamentary sovereignty so as to imply that referendums were alien to the British way. Meanwhile, a novel constitutional body that was never consented to in any general election or referendum—the Supreme Court—became an instrument used by various petitioners looking in one way or another to frustrate the UK government’s discretion to pursue Brexit.

Through the Supreme Court’s involvement, the idea that had underpinned two referendums—namely, that the British people had sovereign authority to decide to end EU membership—faltered. As it did, so the constitutional rules with which the Supreme Court chose to engage also became more contested: soon the government’s opponents in the courts were deploying arguments to assert parliament’s rights deriving from a distinct Scottish constitutional tradition at odds with a singularly English one.

Court short

The Supreme Court’s first important ruling came in January 2017, the so-called Miller 1 case. The High Court had previously accepted Gina Miller’s case that since Brexit would end legal rights created by parliament, the UK government could not fall back on the Crown’s prerogative powers to trigger Article 50. Potentially lethally for the British government, the reasoning invoked to justify restricting its power appeared to erode the distinction between “reserved” matters, like EU membership, and devolved policy areas. Recognising the potentially massive implications, the Scottish and Welsh governments joined the case to argue that Holyrood and the Senedd had to consent before Westminster could trigger Brexit. In this instance, the Supreme Court shied away from the implications of the High Court’s earlier judgment, which taken to its logical conclusion would have granted a Scottish and Welsh Brexit veto.

But the Supreme Court could not banish the pressure the Union now placed on the constitution. Even as it acted more obviously as a constitutional court than ever before, it sowed doubts about whether there was in fact a unified British constitution for the judges to arbitrate. In Miller 1, the Court upheld the petitioners’ use of the pre-Union Scottish Claim of Right. In accepting this move, it asserted that the Scottish constitutional tradition was not extinguished by the Act of Union. That claim wasn’t new—Scottish nationalists have maintained as much since the mid 20th century—but it is hard to square with any idea that the constitution serves and stabilises the Union.

Since neither Theresa May nor Boris Johnson’s minority governments had the votes to pass their respective withdrawal agreements in the 2017-2019 parliament, and since MPs were unwilling to allow a no-deal exit, the Supreme Court remained a potential constraint on the executive and an opportunity for the opposition. In proroguing parliament in August 2019, Johnson overstepped the new judicial limits, inviting the opponents of Brexit to ask for them to be pushed further. In its ruling adjudicating between the completely opposed prior rulings offered by the highest English and Scottish courts, the Supreme Court made itself the arbiter of constitutional conventions. It also accepted the notion that there was pre-Union foundational constitutional law from Scotland governing the relationship between parliament and the executive.

Mistakes and high stakes

In making his case for the comparative virtues of a British constitutional way over the EU’s “simulacrum of a sentient democracy,” dependent on decree and subterfuge, Perry Anderson insists that the difference turns on the “fact… that British governments can only survive if they enjoy a majority in the Commons… and if they fall, elections to replace them must ensue.” In this, however, he misses the force of the one constitutional change made by the 2010-2015 parliament without a referendum: the Fixed-term Parliaments Act. Without it, Johnson could have dissolved parliament for a general election before the Supreme Court ruled in Miller 2. With it, in the autumn of 2019 a majority in parliament locked in office a government that didn’t enjoy the support of the Commons—and shut voters out from their place in the constitution.

But even in this constitutional void, the adversarial habits between parties bred by the old British constitutional order died hard. During the crucial September and October weeks, there were simply too few MPs willing to countenance making Jeremy Corbyn prime minister, and the Labour leadership was unwilling to support an alternative figure. In the resulting stasis, and confronted with the misplaced confidence of the Lib Dems and well-founded convictions of the SNP about their election prospects, the Labour leadership finally succumbed to Johnson’s push for an election.

Once the voters were reintroduced into proceedings, the final decision to leave the EU eventually found its Diceyan resolution in a choice of the British people—albeit, ultimately, one expressed indirectly in a general election rather than the 2016 referendum. That 2019 election became what the EU’s court-centric constitutional order inhibits: a high-stakes political contest where radically different outcomes were real possibilities.

“Try and keep questions of consent at bay, and the place where they manifest mutates”

The one that prevailed has only made likely more such contests in relation to the UK Union. The constitutional order as it applies to Scotland and Northern Ireland now has undeniably changed without the expressed consent of Scottish and Northern Irish voters, who had neither backed Brexit in 2016 nor returned Conservative majorities in 2019. Although in the case of Scotland, Westminster holds the legal authority over a referendum, the argument that the political consent of Scottish and Northern Irish voters with regards to the Union can be subject to another high-stakes test of consent is hard to rebut.

Indeed, the distinct premium on consent—and the fact that such contests are ultimately hard to avoid in British politics—is a part of what made the UK unsuited for EU membership. Although the states that joined the EC with Britain held referendums prior to accession, and they and several others went on to hold votes on treaties, there is one clear difference around the seriousness with which consent is taken: no EU state recognises a unilateral right of secession of any part of its territory in the way that such a right is understood to apply to at least the non-English parts of the UK.

That certainly makes it likely there will be difficult times ahead for the Union. But forms of democratic politics structured to manufacture consensus and keep questions of consent at bay cannot make them permanently disappear. Rather, the places where they manifest mutate. After French voters rejected the EU constitutional treaty, the hitherto referendum-orientated Fifth Republic dispensed with them. Instead, in 2017, it ended up with an unusually high-stakes presidential election, after neither candidate from the two principal parties made it to the second round. Emmanuel Macron prevailed over the hard-right Marine Le Pen by promising to make Europe more French again, only to find the EU’s structures less than pliable to French election results and democratic discontent on the French streets. Weakened, the French Republic must next year be put to existential test again.

For the UK, the demands of consent remain onerous. It is easier to govern if these questions don’t have to be asked. But the Union has already been subject to such constitutional change and the constitution become too complicated by the Union for the status quo to endure for long. There is still a lot more of the politics of consent to come, including in relation to England, and it is incumbent upon politicians to grasp this. If they fail to understand how we have got here, and why consent keeps rearing its head, they and the Union will eventually pay the price.