Before the 2017 election, Labour had held Mansfield for 95 years. This is not to suggest that Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership is solely or even principally to blame for this particular loss. But there is no doubt that the Corbyn surge has changed the complexion of Labour’s electoral base.

Brexit is a crucial part of this story—but not the whole picture. Mansfield’s support for leaving the EU in June 2016 was 70 per cent. But this archetypal ‘left behind’ town has been moving away from Labour for a very long time. Its directly-elected mayoralty has been held by right-leaning ‘independent’ candidates since the post’s creation in 2002. Conservatives have also, generally speaking, been catching up to Labour at general elections there since 1997.

The constituency has one of the highest concentrations of working-class voters in England. 60 per cent of the residents of the local authority area are categorised as social grades C2 (skilled manual workers) or DE (semi-skilled, unskilled and unemployed), compared to an English average of 46 per cent.

While the details are complex, then, we can see Labour’s loss of Mansfield as part of a long run national trend of working class voters deserting the Labour Party. IpsosMori voting data shows C2 support steadily declining from around 50 per cent in 1997 to 30 per cent in 2010, and DE support declining from around 60 per cent to around 40 per cent over the same period.

At the same time, working-class support for the Conservative Party has risen steadily across recent elections, now almost matching its early 1980s peak. As such, the Conservative Party now leads Labour among C2 voters by 4 percentage points, rising from an even share with Labour in 2015. And the Conservative Party has closed the gap among DE voters to 9 percentage points, having been 15 points behind in 2015.

Labour picked up working-class vote share too (benefiting from a collapse of working-class supportfor the SNP and the Green Party), but its surge was based mainly on a remarkable uptick in support among AB and C1 voters (managerial and professional workers). Incredibly, the spread of support by class is now fairly even for both main parties.

A younger support base?

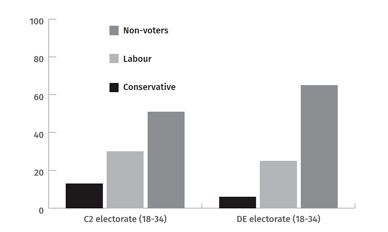

The silver lining that Labour figures have persistently pointed to since the election is that the party’s vote share among young working-class voters appears to have been particularly strong—but all is not as it seems. Labour won 62 per cent of the vote share among C2 voters aged 18–34 (compared to 27 per cent for the Conservatives), and 70 per cent of the DE vote in the same age group (compared to 18 per cent for the Conservatives).“Turnout among working-class young people is depressingly low”However, turnout among working-class voters remains very low—especially the young. C2 turnout was only 60 per cent in 2017, and DE turnout was only 53 per cent. Furthermore, turnout among working-class young people is depressingly low. C2 turnout in 2017 among voters aged 18–34 was only 49 per cent, and DE turnout was only 35 per cent (young C1 turnout, in contrast, was above the overall turnout rate for all ages).

Here is the IpsosMori voting data by class and age with non-voters included:

It is possible to conclude that the Conservatives are now a party with strong working-class support and that Labour is recovering lost ground among its working-class base. The most important (and least refutable) story emerging from the 2017 general election in this regard, however, is that the working class remains disproportionately disengaged from formal politics.

The Mansfield Test

There is nothing wrong with Labour attracting more middle-class votes. The party needs to forge alliances across socio-economic groups to win a majority in parliament. Yet a celebration of the unexpected but commendable feat of gaining 30 seats must at some point give way to consideration of how a further 64 seats will be gained to secure a parliamentary majority.The Conservative Party’s own surge among working-class voters contributed to its enormous 42.4 per cent overall vote share. This was, incredibly, almost matched by Labour—but the Conservative vote is more evenly spread, enabling the party to emerge as the largest party by a considerable margin. Of course, there are relatively few constituencies like Mansfield, so it would be wrong to assume that reinforcing the party’s appeal to working-class voters in other ‘left behind’ towns would produce a stable majority for the Conservatives at the next election.

However, this argument is a bit of a red herring. The first-past-the-post system means that the Conservative Party does not need to win all of the predominantly working-class constituencies competed over by Labour and UKIP at the 2015 election, for instance, to win a majority.

A handful of Mansfields would help, but the more important goal for the Conservative Party is winning back its own supporters in suburban areas. This is far more achievable as long as the working-class vote in these areas remains depressed.

Labour's working-class wobbles

There are a number of problems when it comes to the treatment of the working class in the imaginary of the contemporary centre-left. The first is the belief that there are increasingly few differences between working- and middle-class interests. We may indeed be witnessing a ‘proletarianisation’ of the economic experience of some middle-class groups, particularly among the young. But economic precariousness is, overwhelmingly, an affliction of the traditional working class.Another is explained via a pseudo-Marxist false consciousness thesis, in which the working class are deemed incapable of understanding their own socio-economic interests. Central to this is a predilection to portray the present moment as a historical juncture; that is, an interregnum between distinct historical periods.

This provides a comforting frame for Corbynism, since it compels an immediate mobilisation of socialist forces, irrespective of working-class support, in order to capitalise on a weakening of neoliberal normativity—as Jeremy Gilbert haseloquently described.

The notion that the working class are to any extent apolitical must be banished from Labour thinking, especially insofar as it justifies the vanguardism that characterises the perspective of current party and trade union leaders. In practice, the experience of capitalism by working class groups has always been heavily politicised, but manifests as an interest in both liberation from and reproduction of their class status. For working-class people, this contradiction is not a theoretical problematique, but rather a crushing, everyday dilemma.

Unfortunately, this is a notion which also finds a home among some of those opposed to Corbyn’s leadership, who remain tied to a flawed ‘Blue Labour’ perspective. What started out an important critique of New Labour's managerialist state, inspired by communitarian thought, has morphed into self-parody, as Blue Labour adherents too eagerly replace the class politics of inequality with the class politics of culture.

They apotheosise the image of the white, English manual worker in the process, while depriving this agent of their experience of exploitative economic relations, instead fetishising their experience of place and ‘belonging’.

A new settlement

Corbyn is not responsible for Labour’s acquaintance with the actually-existing working class having been lost, but it is essential that action is taken now to resolve the problem. Labour needs a policy offer for the working class with a radical approach to social security and employment rights. The leadership also needs to make a determined effort to elevate people from working-class backgrounds to the highest ranks of the party.A decisive shift of internal culture is needed: away from members debating policies among themselves, and towards genuine deliberation with working-class communities. Structural change – such as the comprehensive federalisation of the party within England—would assist this agenda.

There is also work to be done by the trade union movement. Trade unions should become more important to Labour, but only on the basis that they become more representative of the working class. If existing unions are reluctant to change, Labour must support and drive the creation of new forms of trade unionism.

Labour stands at a critical juncture. The stubbornness (and exacerbation) of class-based inequalities shatters the illusion upon which much of Labour’s recent statecraft has been founded. But while the party’s shift leftwards clearly offers an opportunity to re-root Labour in the working class—while acknowledging its complexities—there are few signs at present that this opportunity is being realised.

This article is from IPPR’s latest Progressive Review issue. Read more here.