Read more by Peter Kellner: How prejudiced are we anyway?

In the depths of America’s Great Depression in the 1930s, two songs captured the tussle between rival sentiments—Yip Harburg’s pessimistic refrain, “Brother, can you spare a dime?” and the upbeat anthem adopted by Franklin D Roosevelt’s campaign for the presidency, “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

Since George Osborne became Britain’s Chancellor almost six years ago, his tone has been that of Harburg. YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect, ahead of this spring’s Budget, suggests the time has come for Osborne to sound more like FDR. Despite the long years of austerity, and the repeated incantation of the need to make tough choices, voters are actually upbeat. The near-despair of seven years ago, when the economy was at its weakest, has given way to a palpable optimism.

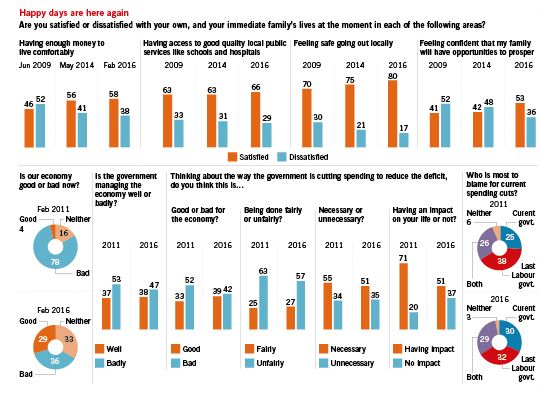

We started by repeating four questions about the underlying public mood that we first asked in 2009 and asked again in 2014. In every case, British people have become more cheerful. Seven years ago, just 41 per cent were confident that “my family will have the opportunities to prosper in the years ahead,” while 52 per cent lacked such confidence—a net score of minus 11. In 2014, we were still in negative territory, with a net score of minus six. Now optimists (53 per cent) outnumber pessimists (36 per cent), making the net score plus 17. There have been similar shifts on “having enough money to live on comfortably,” from minus six in 2009 to plus 20 today, and “feeling safe going out in your area,” from plus 40 to plus 63.

Perhaps the most striking finding concerns “having access to high quality public services in your area, such as schools and hospitals.” True, the change since 2009 has been modest, from plus 30 to plus 37. The most interesting thing is that the shift has been positive at all. For six years, Osborne has sought to cut public spending; and although he has spared schools and hospitals from the cuts suffered by other services, Osborne’s critics have said that the budgets for health and education have failed to keep up with ever-rising demands on them. Yet voters are more content than during the later stages of the last Labour government.

Next, we looked more directly at Osborne’s stewardship of the economy. The graphic (below left) compares public attitudes now with those five years ago, at the same stage in the last parliament. Then the headlines told an almost daily story of falling output. We now know that the economy did not in fact contract in 2011, but the official statistics at the time wrongly reported GDP stuck in recession. No wonder 78 per cent thought the state of the economy was bad. Today, that figure is down to 36 per cent, with 62 per cent saying it is either good (29 per cent in 2011) or neither good nor bad (33 per cent).

As for Osborne’s performance, voters are still on balance critical, with 47 per cent saying the government is managing the economy badly, and just 38 per cent saying well. But there are slightly fewer critics than five years ago. As with voters’ attitudes to public services, what is striking is that there has been any improvement in Osborne’s rating. Five years ago, the Chancellor was able to blame the recently departed Labour government for the need for austerity. Today, almost six years since Gordon Brown left Downing Street, that blame-Labour argument ought to be more difficult to mount.

In fact, the verdict on who is to blame for austerity has changed little. Slightly more people blame the Tories, and slightly fewer blame Labour; but after so long in office, the shifts have been remarkably small.

However, were I the Chancellor, the finding that would please me most is the one about the impact of the spending cuts. At first blush the figures look bad: 51 per cent say they have been directly affected, while 37 per cent say they have not. But five years ago, far more people, 71 per cent, said they had been affected, while only 20 per cent said they had not.

That is odd, for in 2011 hardly any of the cuts had been implemented, yet most people said they had been hurt by them. Now, after spending in many areas has been reduced, fewer people sense any impact on their own lives. I suspect the figures five years ago measured the fear of cuts—which means that for almost 10m voters (the difference between 71 and 51 per cent), those fears have not come to pass.

That said, 51 per cent is still a worrying number; and there are many who say that what we have seen so far have been the “easy” cuts: from now on the “hard” cuts really will affect daily life for millions of people. If so, the percentage will start to rise.

That makes it even more important for Osborne not just to decide the right measures in the coming Budget, but to strike the right tone. Our figures suggest that he has an opportunity to exploit a wide sense of optimism, and that even if he has not finished taking tough decisions, he places himself firmly with those who see a bright future. As a keen student of political history, the Chancellor knows that “Happy Days Are Here Again” inaugurated the New Deal and 20 years of Democratic rule in the United States—and that here, “Things Can Only Get Better” in 1997 led to Labour’s longest period of government.

Or, if those examples from the left do not appeal to him, he can always resort to Winston Churchill. In 1940, in Britain’s darkest hour, the new Prime Minister balanced warnings of “blood, sweat and tears” with the promise that in the end, we would reach “the sunlit uplands.” As long as he is careful not to overstate the case for optimism, Osborne might be surprised at how well a sensibly positive story would go down with the public. Peter Kellner is President of YouGov

Now read: Do we want Trident?

In the depths of America’s Great Depression in the 1930s, two songs captured the tussle between rival sentiments—Yip Harburg’s pessimistic refrain, “Brother, can you spare a dime?” and the upbeat anthem adopted by Franklin D Roosevelt’s campaign for the presidency, “Happy Days Are Here Again.”

Since George Osborne became Britain’s Chancellor almost six years ago, his tone has been that of Harburg. YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect, ahead of this spring’s Budget, suggests the time has come for Osborne to sound more like FDR. Despite the long years of austerity, and the repeated incantation of the need to make tough choices, voters are actually upbeat. The near-despair of seven years ago, when the economy was at its weakest, has given way to a palpable optimism.

We started by repeating four questions about the underlying public mood that we first asked in 2009 and asked again in 2014. In every case, British people have become more cheerful. Seven years ago, just 41 per cent were confident that “my family will have the opportunities to prosper in the years ahead,” while 52 per cent lacked such confidence—a net score of minus 11. In 2014, we were still in negative territory, with a net score of minus six. Now optimists (53 per cent) outnumber pessimists (36 per cent), making the net score plus 17. There have been similar shifts on “having enough money to live on comfortably,” from minus six in 2009 to plus 20 today, and “feeling safe going out in your area,” from plus 40 to plus 63.

Perhaps the most striking finding concerns “having access to high quality public services in your area, such as schools and hospitals.” True, the change since 2009 has been modest, from plus 30 to plus 37. The most interesting thing is that the shift has been positive at all. For six years, Osborne has sought to cut public spending; and although he has spared schools and hospitals from the cuts suffered by other services, Osborne’s critics have said that the budgets for health and education have failed to keep up with ever-rising demands on them. Yet voters are more content than during the later stages of the last Labour government.

Next, we looked more directly at Osborne’s stewardship of the economy. The graphic (below left) compares public attitudes now with those five years ago, at the same stage in the last parliament. Then the headlines told an almost daily story of falling output. We now know that the economy did not in fact contract in 2011, but the official statistics at the time wrongly reported GDP stuck in recession. No wonder 78 per cent thought the state of the economy was bad. Today, that figure is down to 36 per cent, with 62 per cent saying it is either good (29 per cent in 2011) or neither good nor bad (33 per cent).

As for Osborne’s performance, voters are still on balance critical, with 47 per cent saying the government is managing the economy badly, and just 38 per cent saying well. But there are slightly fewer critics than five years ago. As with voters’ attitudes to public services, what is striking is that there has been any improvement in Osborne’s rating. Five years ago, the Chancellor was able to blame the recently departed Labour government for the need for austerity. Today, almost six years since Gordon Brown left Downing Street, that blame-Labour argument ought to be more difficult to mount.

In fact, the verdict on who is to blame for austerity has changed little. Slightly more people blame the Tories, and slightly fewer blame Labour; but after so long in office, the shifts have been remarkably small.

However, were I the Chancellor, the finding that would please me most is the one about the impact of the spending cuts. At first blush the figures look bad: 51 per cent say they have been directly affected, while 37 per cent say they have not. But five years ago, far more people, 71 per cent, said they had been affected, while only 20 per cent said they had not.

That is odd, for in 2011 hardly any of the cuts had been implemented, yet most people said they had been hurt by them. Now, after spending in many areas has been reduced, fewer people sense any impact on their own lives. I suspect the figures five years ago measured the fear of cuts—which means that for almost 10m voters (the difference between 71 and 51 per cent), those fears have not come to pass.

That said, 51 per cent is still a worrying number; and there are many who say that what we have seen so far have been the “easy” cuts: from now on the “hard” cuts really will affect daily life for millions of people. If so, the percentage will start to rise.

That makes it even more important for Osborne not just to decide the right measures in the coming Budget, but to strike the right tone. Our figures suggest that he has an opportunity to exploit a wide sense of optimism, and that even if he has not finished taking tough decisions, he places himself firmly with those who see a bright future. As a keen student of political history, the Chancellor knows that “Happy Days Are Here Again” inaugurated the New Deal and 20 years of Democratic rule in the United States—and that here, “Things Can Only Get Better” in 1997 led to Labour’s longest period of government.

Or, if those examples from the left do not appeal to him, he can always resort to Winston Churchill. In 1940, in Britain’s darkest hour, the new Prime Minister balanced warnings of “blood, sweat and tears” with the promise that in the end, we would reach “the sunlit uplands.” As long as he is careful not to overstate the case for optimism, Osborne might be surprised at how well a sensibly positive story would go down with the public. Peter Kellner is President of YouGov

Now read: Do we want Trident?