A “dangerous cocktail” of economic turmoil in China and collapsing oil prices now threatens Britain’s economic and government policies, according to George Osborne. But the strange thing about these two risks is that they both require a response exactly opposite to the one the Chancellor promised: determination to stick to the government’s pre-existing economic plans come hell or high water.

Luckily, Osborne’s record of politically adroit U-turning suggests that he may already understand this, and in fact plans to do the opposite of what he promised. If China really does descend into chaos this will provide a perfect excuse to suspend fiscal targets that were going to be missed anyway and instead ease up on austerity, while declaring more loudly than ever that “there is no alternative” to the abandoned targets. And if oil prices stay at their present rock-bottom levels this will create a golden opportunity to reconsider some of the government’s misguided priorities on tax and spending, while claiming that the original decisions were the right ones in the different circumstances that were prevailing when they were made.

China is a mystery wrapped in an enigma and will probably muddle its way through its present problems, as described here two months ago; but a Chinese collapse, though it remains unlikely, is a genuine threat to the world economy—and would have to be met with the opposite of the policies Osborne advocated in his “dangerous cocktail” speech. Austerity would have to be replaced with fiscal stimulus, near-zero interest rates would have to be continued for longer and Conservative euro-sceptics would have to abandon their fantasy about trading China as a substitute for Britain’s natural inter-dependency with the European Union.

The implications of a collapsing oil price are even more at odds with the Chancellor’s apparent views. Cheap oil, far from being a mortal danger, is an unqualified blessing for the British economy and could be an even greater boon to the government.

Contrary to stockmarket lore, falling oil prices do not portend a global economic downturn. On the contrary, every global recession since 1970 has been preceded by a sharp rise in the price of oil. And almost all of the previous occasions when oil prices have fallen by 40 per cent or more have been followed by sharp accelerations in global growth: in 1985-86, 1992-93, 1997-98 and 2001-02. The most spectacular instance of the oil price acting as a contrary indicator of economic activity was also the most recent and should surely have stuck in the Chancellor’s mind. In the year leading up to the global depression of 2008, the oil price trebled, from $50 to $140. It then plunged back from $150 to $40 in the six months that immediately presaged the global economic recovery of 2009-10.

"Osborne's record of politically adroit U-turning suggests that he plans to do the opposite of what he promised"

A convincing economic explanation exists for this negative correlation between oil prices and global growth. Each year the world burns about 34bn barrels of oil, which means that every $10 fall in the oil price shifts $340 billion from oil producers to consumers. Thus the $70 price decline of the past 18 months will redistribute about $2.3 trillion annually to oil consumers, providing a bigger income boost than the combined fiscal stimuli of the United States and China in 2009. Oil consumers eventually spend their extra incomes, although it may take them a year or so before they fully appreciate the windfall. Meanwhile the oil-producing governments which collect over 80 per cent of global oil revenues usually keep spending, first by running down financial savings and then by borrowing for as long as they can. That, after all, is what comes naturally to most politicians, especially when they are fighting wars, like Saudi Arabia, or defying geopolitical pressures, like Russia. The net effect of the enormous income redistribution to consumers from oil producers should therefore be to accelerate global growth, as has always happened after oil has collapsed in the past.

So what does all this imply for Britain and George Osborne? While a crisis in China is a genuine and potentially catastrophic risk, it is unlikely to materialise in the year ahead. The Chinese authorities, despite their many false moves since last summer, have the necessary policy instruments to prevent an orderly slowdown degenerating into an economic collapse. And in the unlikely event that the Chinese authorities do seriously mismanage their economic restructuring, Britain has plenty of scope to protect itself by easing up on fiscal austerity and delaying any moves to raise interest rates.

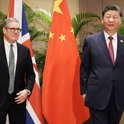

Read more on UK-China relations:

Are we really entering a “golden” relationship with China?

Is Osborne making a mistake in China?

Meanwhile, and regardless of any threats from China, the collapse of oil prices is now an accomplished fact that creates immediate opportunities to improve economic performance and government policy.

If Osborne is serious about strengthening government finances, he should take advantage of falling oil prices in his next Budget to increase duties on petrol, especially on diesel. Even more importantly he should restore the automatic annual escalation of fuel duties by 3 to 5 per cent above the rate of inflation. This permanent and automatic “fuel duty escalator” was the Major government’s most effective instrument for repairing public finances after the 1992-93 financial crisis. The next Budget would also be an ideal opportunity to abolish the winter fuel allowance for pensioners—and then observe the political impact.

If the removal of this inequitable and patronising handout to pensioners were greeted with support from the public, rather than the backlash dreaded by Tory politicians, it could act as a precedent for a desperately needed shift in Britain’s government spending priorities away from affluent elderly voters towards the genuinely needy and the working poor.

Such a rebalancing of spending and revenues—steadily increasing energy taxes and gradually reducing pensioner handouts—is a much more plausible mechanism for permanently improving Britain’s public finances than unsustainable cuts to core public services or Osborne’s gimmicky tax reforms.

The confluence of events in China and global oil markets gives Osborne an opportunity to raise energy taxes and abolish fuel subsidies, while easing the government’s existing austerity programmes. Such a combination of measures would strengthen the economy, increase work incentives, promote social justice, restore Britain’s leadership in environmental technologies and transform the long-term prospects for public finances. Here, finally, is a genuine chance for Osborne to inject some substance into his mantra about “fixing the roof while the sun is shining.”

Next month’s Budget would be the perfect time to start.