Post Truth: Why We Have Reached Peak Bullshit and What We Can Do About It by Evan Davis (Little, Brown, £14.99)

Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back by Matthew D’Ancona (Ebury Press, £6.99)

Post-Truth: How Bullshit Conquered the World by James Ball (Biteback Publishing, £9.99)

Here are three distinguished journalists, and three books on the same subject. Each one takes its title from the Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year for 2016, where “post-truth” was defined as an adjective “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Each is in part a response to the successes of the mendacious Donald Trump campaign and the disgraceful Brexit propaganda of the referendum. Each laments that social media and other dark arts of new technology have unprecedented power to manipulate and mislead a huge proportion of the population. The authors are to be congratulated on being among the first, although surely not the last, to ponder the meaning of the political disasters of 2016 and to worry about the climate that gave birth to them.

The similarity of the three books goes beyond their titles. Each realises that Trump and Brexit have economic and social causes, as swathes of the population, rightly believing themselves ignored and left behind by the Westminster bubble or Washington swamp, fell for the blandishments of simple, populist solutions. But it is not the economic and social causes of these upheavals that bother them. It is the danger that we are drowning in misinformation. We are all at sea, having no landmarks, no bearings, no ways of navigating the tides of spin, lies, bullshit and manipulations that assail us on every side. For every BBC there is a Fox News; for every reliable website there are dozens that peddle lies. So we need to reflect more and trust our “gut” less; we need to cultivate scepticism; we need fact-checkers, (or even fact-checker-checkers, and so on without end, for Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?); we need to find ways of publishing corrections far and wide, and so on.

All three authors are the kind of cocksure empiricists who have been embarrassed by the election result. Davis, an economist and a familiar face and voice from the BBC, shows the widest appreciation of the many ways in which people have always been economical, or worse, with the truth. He is thus slightly less panic-stricken about our present situation, and argues that above all we have to be tough on credulity. James Ball, whose career began at WikiLeaks before progressing to the Guardian, is now at the online news website BuzzFeed. As befits an ex-editor of the Spectator, D’Ancona is the most apocalyptic of the three, talking rousingly of Orwellian disaster, battles which we cannot shirk, tasks of responsible citizenship, and the decay of civilisation. So in spite of these differences of nuance each of them urges that Something Must be Done.

It is, of course, hard to disagree. But we might at least note that if the Oxford definition intends to describe a world in which the very concept of truth is under assault, then there is a paradox lurking inside it. To say that objective facts are now less influential in shaping opinion than appeals to emotion implies that there are such things as objective facts. In a truly post-truth environment, where the whole concept of truth had lost purchase, this claim would not be made or even understood. Similarly you cannot use the concept of bullshit without implicitly relying on a corresponding conception of truth. In Harry Frankfurt’s admired account On Bullshit (2005), which our authors cite, the specific vice of bullshitters is that they make statements without having the concern for truth that is common to both truth-tellers, who want to relate it, and liars, who want to relate its opposite. So making sense of bullshitting implies making sense of truth and concern for the truth. It is only by contrast with these that bullshit can exist, just as counterfeit coins presuppose real coins.

Even post-modernists, whom D’Ancona fingers as bearing some responsibility for our current woes, did so. When post-modernists echoed Nietzsche’s claim that “there are no facts, only interpretations,” they were not belittling the process of interpretation. On the contrary, Nietzsche’s aphorism highlights the importance of weighing up rival claims: it means that it takes experience, care, judgment and skill to fill our minds with sensible beliefs. Some such skills are unavoidable. To get through life, the philosopher of deconstruction Jacques Derrida needed to know things such as the time of his train, the fare on his taxi, or whether his shoes were on the right feet. And even serial bullshitters know the difference between getting something right and getting it wrong. A poor deluded mother might give credence to the baseless claim that vaccination causes autism, but she will not believe that you can walk all the way from the United States to Britain. In countless everyday areas we have our feet sufficiently on the ground. The term “post-truth,” then, is itself fake news.

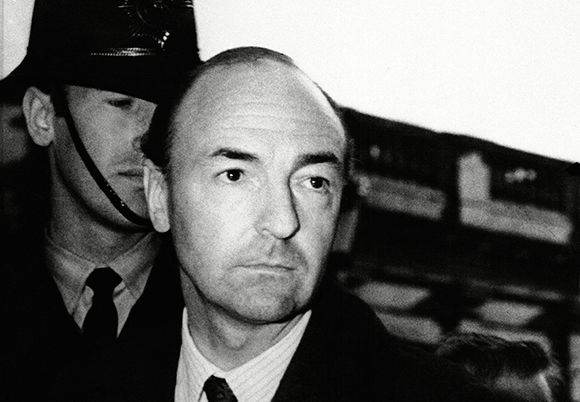

Nevertheless, real worries about our age remain. “Post-shame” and “post-trust” might be better adjectives, insofar as public figures are not in the least ashamed of being proven bullshitters or liars, and people can no longer be sure who, if anyone, to trust. The one is a moral problem and the other a very different epistemological problem. They are both real enough. To take the first, it is surely true that politicians are now more prepared simply to shrug off proven spin and outright mendacity: there is a big moral gap between 1963 which saw John Profumo’s inevitable resignation, after it was clear that he had lied to the House of Commons, and the blithe insouciance of “Hey, let’s just move on, OK?”, which is the stock-in-trade of contemporary politicians caught with their pants on fire. However perjury remains a grave crime, nothwithstanding Bill Clinton’s semantic agility in fending off the charge in 1998. And while Boris Johnson may giggle at being discovered to bullshit, the rest of us cannot afford to find it amusing.

The problem of knowing whom or what to trust is tied up with a moral problem. When trustworthiness is regarded as one option among others, with few penalties for departures from it, people are wise to trust their sources less. The anonymity of the web means that the usual reputational effects and other sanctions against misinformation fail to apply, and predictably when there are no costs to bear, anything goes. Yet people continue to believe stuff they read online in spite of this: as the philosopher CS Peirce noticed, it is uncomfortable to be in a state of doubt, and one way of allaying the discomfort is to plump for any certainty on offer, and especially any certainty that ties in with our previous world-view, or even that we just find entertaining to contemplate.

So we get people who are too often gullible and credulous, and apt to live in echo chambers in which only things that accord with their own opinions are heard. Conspiracy theories abound, ludicrous claims are given the same air-time as sober science, one-third of Americans believe, or say they believe, that dinosaurs co-existed with early hominids, around six thousand years ago, and others believe that Trump’s hair is real, just as some British believe that Nigel Farage is a man of the people. Too many people make little attempt, or no attempt, to master the ways in which a putative fact may properly earn the accolade of being objective, or in other words sufficiently established by observation, inference, testing and control: the proven devices which we all instinctively use in our everyday lives, and with which science has conquered so many new territories.

Perhaps we do need to be tough on credulity. But here as elsewhere the language of crisis, battle and war, is out of place. A better recipe might be to be gentle with the gullible, or in other words carefully and patiently introduce people to the virtues of the well-conducted mind. It is sad that a childhood innocence that regards everyone as trustworthy has to be replaced, but it does. The process is called education. Its heart ought to be an appreciation of probability, of inference to the best explanation, of the intuitive use of statistical reasoning, or in short, epistemology. Yet how many people leave school, either in the UK or in the US, with the slightest grasp of scientific method, or of what are the marks of its distinctive virtues? How many ministers of education have actually come across the long traditions of epistemology? How many have read or understood the many resources in the philosophical tradition for opposing credulity?

At the start of his essay Hume flattered himself that he had found an argument which will “with the wise and the learned, be an everlasting check to all kinds of superstitious delusion, and consequently will be useful as long as the world endures.” And he had done exactly that, but how many children or teachers have the first inkling of his achievement? At present only a tiny minority of A-level students study philosophy, and a vigorous attempt to make it a GCSE subject has met only apathy from the same Department of Education that is instead so inexplicably keen on testing whether young children can say what a fronted adverbial phrase or a modal auxiliary is.

We should welcome these three books since, even if they shy away from putting it in these terms, they make an overwhelming case for a genuinely philosophical education.

Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back by Matthew D’Ancona (Ebury Press, £6.99)

Post-Truth: How Bullshit Conquered the World by James Ball (Biteback Publishing, £9.99)

Here are three distinguished journalists, and three books on the same subject. Each one takes its title from the Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year for 2016, where “post-truth” was defined as an adjective “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Each is in part a response to the successes of the mendacious Donald Trump campaign and the disgraceful Brexit propaganda of the referendum. Each laments that social media and other dark arts of new technology have unprecedented power to manipulate and mislead a huge proportion of the population. The authors are to be congratulated on being among the first, although surely not the last, to ponder the meaning of the political disasters of 2016 and to worry about the climate that gave birth to them.

The similarity of the three books goes beyond their titles. Each realises that Trump and Brexit have economic and social causes, as swathes of the population, rightly believing themselves ignored and left behind by the Westminster bubble or Washington swamp, fell for the blandishments of simple, populist solutions. But it is not the economic and social causes of these upheavals that bother them. It is the danger that we are drowning in misinformation. We are all at sea, having no landmarks, no bearings, no ways of navigating the tides of spin, lies, bullshit and manipulations that assail us on every side. For every BBC there is a Fox News; for every reliable website there are dozens that peddle lies. So we need to reflect more and trust our “gut” less; we need to cultivate scepticism; we need fact-checkers, (or even fact-checker-checkers, and so on without end, for Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?); we need to find ways of publishing corrections far and wide, and so on.

All three authors are the kind of cocksure empiricists who have been embarrassed by the election result. Davis, an economist and a familiar face and voice from the BBC, shows the widest appreciation of the many ways in which people have always been economical, or worse, with the truth. He is thus slightly less panic-stricken about our present situation, and argues that above all we have to be tough on credulity. James Ball, whose career began at WikiLeaks before progressing to the Guardian, is now at the online news website BuzzFeed. As befits an ex-editor of the Spectator, D’Ancona is the most apocalyptic of the three, talking rousingly of Orwellian disaster, battles which we cannot shirk, tasks of responsible citizenship, and the decay of civilisation. So in spite of these differences of nuance each of them urges that Something Must be Done.

It is, of course, hard to disagree. But we might at least note that if the Oxford definition intends to describe a world in which the very concept of truth is under assault, then there is a paradox lurking inside it. To say that objective facts are now less influential in shaping opinion than appeals to emotion implies that there are such things as objective facts. In a truly post-truth environment, where the whole concept of truth had lost purchase, this claim would not be made or even understood. Similarly you cannot use the concept of bullshit without implicitly relying on a corresponding conception of truth. In Harry Frankfurt’s admired account On Bullshit (2005), which our authors cite, the specific vice of bullshitters is that they make statements without having the concern for truth that is common to both truth-tellers, who want to relate it, and liars, who want to relate its opposite. So making sense of bullshitting implies making sense of truth and concern for the truth. It is only by contrast with these that bullshit can exist, just as counterfeit coins presuppose real coins.

"It is surely true that politicians these days are more prepared simply to shrug off proven spin and outright mendacity"Of course, thinking we are “post-” anything implies nostalgia for a past that might itself be mythological. Could there ever have been a world in which appeals to emotion and personal belief were less powerful than appeals to objective fact? To take emotion first, it is hardly a new phenomenon that people’s opinions are moved by their hopes, grievances and fears. And is it really sensible to contrast “personal belief” with “objective fact”? In order to move people, objective facts must become personal beliefs. It is only insofar as I believe that there is a bus bearing down on me that I jump out of its path. Were there a bus bearing down on me (“objectively”) but I could neither sense it directly nor receive clues about its coming, I would not bother to jump, and my fate would illustrate the advantage—nay, the necessity—of aligning personal belief with objective fact. In sum, everyone has always thought that some things are true, and everyone wonders and has always wondered whether others are.

Even post-modernists, whom D’Ancona fingers as bearing some responsibility for our current woes, did so. When post-modernists echoed Nietzsche’s claim that “there are no facts, only interpretations,” they were not belittling the process of interpretation. On the contrary, Nietzsche’s aphorism highlights the importance of weighing up rival claims: it means that it takes experience, care, judgment and skill to fill our minds with sensible beliefs. Some such skills are unavoidable. To get through life, the philosopher of deconstruction Jacques Derrida needed to know things such as the time of his train, the fare on his taxi, or whether his shoes were on the right feet. And even serial bullshitters know the difference between getting something right and getting it wrong. A poor deluded mother might give credence to the baseless claim that vaccination causes autism, but she will not believe that you can walk all the way from the United States to Britain. In countless everyday areas we have our feet sufficiently on the ground. The term “post-truth,” then, is itself fake news.

Nevertheless, real worries about our age remain. “Post-shame” and “post-trust” might be better adjectives, insofar as public figures are not in the least ashamed of being proven bullshitters or liars, and people can no longer be sure who, if anyone, to trust. The one is a moral problem and the other a very different epistemological problem. They are both real enough. To take the first, it is surely true that politicians are now more prepared simply to shrug off proven spin and outright mendacity: there is a big moral gap between 1963 which saw John Profumo’s inevitable resignation, after it was clear that he had lied to the House of Commons, and the blithe insouciance of “Hey, let’s just move on, OK?”, which is the stock-in-trade of contemporary politicians caught with their pants on fire. However perjury remains a grave crime, nothwithstanding Bill Clinton’s semantic agility in fending off the charge in 1998. And while Boris Johnson may giggle at being discovered to bullshit, the rest of us cannot afford to find it amusing.

The problem of knowing whom or what to trust is tied up with a moral problem. When trustworthiness is regarded as one option among others, with few penalties for departures from it, people are wise to trust their sources less. The anonymity of the web means that the usual reputational effects and other sanctions against misinformation fail to apply, and predictably when there are no costs to bear, anything goes. Yet people continue to believe stuff they read online in spite of this: as the philosopher CS Peirce noticed, it is uncomfortable to be in a state of doubt, and one way of allaying the discomfort is to plump for any certainty on offer, and especially any certainty that ties in with our previous world-view, or even that we just find entertaining to contemplate.

So we get people who are too often gullible and credulous, and apt to live in echo chambers in which only things that accord with their own opinions are heard. Conspiracy theories abound, ludicrous claims are given the same air-time as sober science, one-third of Americans believe, or say they believe, that dinosaurs co-existed with early hominids, around six thousand years ago, and others believe that Trump’s hair is real, just as some British believe that Nigel Farage is a man of the people. Too many people make little attempt, or no attempt, to master the ways in which a putative fact may properly earn the accolade of being objective, or in other words sufficiently established by observation, inference, testing and control: the proven devices which we all instinctively use in our everyday lives, and with which science has conquered so many new territories.

"Some people believe dinosaurs lived six thousand years ago; others think Trump's hair is real and Farage is a man of the people"Of course, it is proverbial that bullshit beats brains, and it was ever thus. Someone who believes, on the say-so of some website, that Hillary Clinton was involved in a child abuse ring operating out of a pizza restaurant, is a credulous idiot, certainly, but not as far removed from reality as the many over the centuries who believed, again on the say-so of others, that after his decapitation St Denis of Paris walked up the hill to Montmartre carrying his head under his arm—or any of the thousands of such stories that embellish so many religious narratives. “The wise,” said David Hume in his great essay debunking belief in such miracles, “lend a very academic faith,”—by which he meant sceptical—“to any report that flatters the passions of the reporter,” and should also beware of reports that they find it especially agreeable to believe.

Perhaps we do need to be tough on credulity. But here as elsewhere the language of crisis, battle and war, is out of place. A better recipe might be to be gentle with the gullible, or in other words carefully and patiently introduce people to the virtues of the well-conducted mind. It is sad that a childhood innocence that regards everyone as trustworthy has to be replaced, but it does. The process is called education. Its heart ought to be an appreciation of probability, of inference to the best explanation, of the intuitive use of statistical reasoning, or in short, epistemology. Yet how many people leave school, either in the UK or in the US, with the slightest grasp of scientific method, or of what are the marks of its distinctive virtues? How many ministers of education have actually come across the long traditions of epistemology? How many have read or understood the many resources in the philosophical tradition for opposing credulity?

At the start of his essay Hume flattered himself that he had found an argument which will “with the wise and the learned, be an everlasting check to all kinds of superstitious delusion, and consequently will be useful as long as the world endures.” And he had done exactly that, but how many children or teachers have the first inkling of his achievement? At present only a tiny minority of A-level students study philosophy, and a vigorous attempt to make it a GCSE subject has met only apathy from the same Department of Education that is instead so inexplicably keen on testing whether young children can say what a fronted adverbial phrase or a modal auxiliary is.

We should welcome these three books since, even if they shy away from putting it in these terms, they make an overwhelming case for a genuinely philosophical education.