Once upon a time—a very specific time—British voters overwhelmingly rejected euroscepticism. In November 1990, a Gallup poll found that 56 per cent regarded membership of the European Union as a good thing; only 13 per cent said it was a bad thing. Never before, or since, has the EU been so popular.

For older readers, November 1990 might ring a bell. It was the month of Margaret Thatcher’s defenestration. The poll tax had come into force in England and Wales earlier that year, and she was toxic. Things came to a head when she returned from an EU summit in a fiercely anti-Brussels mood. Her deputy Geoffrey Howe resigned, and Michael Heseltine’s challenge was soon on. When Gallup asked its question about EU membership, it was in a way a proxy for “whose side are you on”—a prime minister who has lost control of her party, or her widely-respected Tory colleagues, a modernising Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats?

This trip down memory lane illuminates an enduring truth about British public opinion and Europe. Passionate Europhiles and Europhobes have been in a minority: the balance of opinion has always been determined by those who view Europe through the prism of politicians talking about it and the broader news agenda. This was evident very soon after Britain had first joined the Common Market in 1973. The next year, Labour returned to power promising a referendum on the issue, as a device to keep its divided party together. In August 1974, MORI and Gallup polls showed a clear majority for getting out. However, in the referendum campaign, almost every respected mainstream politician—including Thatcher, then enjoying her honeymoon as leader of the Conservative Party—campaigned to stay in, leaving a strange mixture of MPs far from the centre, such as Tony Benn and Enoch Powell, to argue against them. “In” defeated “out” mainly because “moderate” defeated “extreme.”

The next major attempt to get out was in the 1983 general election, when Labour’s manifesto promise to withdraw from the Common Market seemed in tune with the electorate. In November 1982, Gallup’s standard question about Common Market membership found a three-to-one majority for “bad” over “good.” However, six months later, during the election campaign, “good” moved back ahead, outnumbering “bad” by three-to-two. Why the change? Nothing much had happened in Brussels, but Britain was more inclined to follow the lead of the (then pro-EEC) Thatcher, whose ratings had soared after the Falklands War, than the Eurosceptic Michael Foot, with his left-wing manifesto and deeply divided party.

The 2016 referendum, of course, produced a different result from the last two attempts to take Britain out, but the underlying dynamic was the same. As ever, minorities on both sides were passionate about the benefits and drawbacks of membership. But it would be a stretch to say that the campaign engaged voters on integrated supply chains, the European Arrest Warrant or the operation of the single market.

Instead, while about 25-30 per cent on each side were fundamentally for or against the EU, the crucial thing was the way that a third, larger chunk, without strong views either way, broke—and in the end, it ensured an overall vote of 52 per cent for Brexit for a variety of reasons, including immigration, nostalgia and the widening gap between rich and poor. In Labour’s once-industrial heartlands, the loss of factories and jobs over 40 years had coincided with UK membership of the EU. Whatever the reality, many voters detected cause and effect. Unlike 1975 and 1983, pro-Europeans lacked strong standard-bearers. Both David Cameron and Jeremy Corbyn supported “stay” half-heartedly; and they failed to coordinate their campaigns. Boris Johnson was the Leave campaign’s most effective star. Cameron’s frantic attempts to keep him with the Remain campaign testify to how such personalities matter.

“The referendum result fundamentally changed the direction of British politics, but the character of public opinion has carried on much as before”

The referendum result fundamentally changed the direction of British politics, but the character of public opinion has carried on much as before. While minorities on both sides still have strong views, millions of voters in between don’t follow Europe closely or think about it deeply, instead paying attention only when some drama or crisis erupts and then making broad-brush judgments informed by their own lives and which politicians they trust. The nature of the majority at any given time continues to be a product of circumstance: contingent and often temporary.

Bear this in mind when making sense of what has happened to public opinion on Europe since 2016. The series of results for three separate polling questions, each asked regularly since the referendum, allow us to draw out three big points.

The salience of relations with the EU has fluctuated wildly. Ipsos MORI regularly asks people to name the “important issues facing Britain today.” Respondents are unprompted, and encouraged to give more than one answer. In the years running up to 2016, despite the gathering Westminster debate about whether to hold a referendum, the number mentioning Europe or the EU seldom reached 10 per cent. Through 2016 the number climbed towards 50 per cent. It stayed at or a little below that level for much of 2017 and 2018, before rising above 70 per cent last year amid the convulsions surrounding Theresa May’s failure to secure parliamentary approval for her Brexit deal. Once Johnson became Prime Minister, won last year’s election and celebrated the UK’s departure from the EU on 31st January, public concern declined to less than 30 per cent. More recently, as the end of the transition looms and the trade talks have run into trouble, concern rose again, to 51 per cent in September.

Approval of the government’s handling of Brexit has also oscillated, but not in sync with salience. In the second half of 2016, before May set out a timetable for negotiating Brexit, YouGov found that only 20 per cent or so thought the government was handling Brexit well, while around 50 per cent said badly, to give an average net score (the “wells” minus the “badlys”) of minus 30. This balance improved a little in early 2017 as May announced a date for Brexit (intended to be March 2019). The rating peaked the week she called the 2017 election, with a net score of plus five, but the campaign cost the PM her parliamentary majority—and her Brexit rating. There were endless arguments about the direction of Brexit and by December the government’s net “handling Brexit” score dropped below minus 40, and never fully recovered. Between January 2018 and May’s resignation in July 2019, that net score moved within a range of minus 28 and minus 81, the very worst scores coming right at the end as May’s party deserted both her and her repeatedly rejected deal. In Boris Johnson’s early months as PM, with parliament still proving difficult, the net score remained dismal, averaging minus 55. His election victory and the end of the impasse changed that. In the week of 31st January 2020, when Brexit finally happened, “well” and “badly” were in balance. That, though, was as good as it got for Johnson. Brexit had happened, but life after this year’s transition phase remained uncertain. By October, the net score had fallen to minus 31.

The wild variation in both these first two series is a classic sign of an issue that is of profound concern to only a minority of voters. Had the majority followed the Brexit saga with consistent passion and awareness, they would have been less susceptible to whether Brexit was in the news and how it was covered; the numbers would have varied far less from month to month. Instead, the salience of Europe depended on whether Brexit was a major news story, and judgments of the government’s handling of it depended on the vicissitudes of the negotiations and the dramas in parliament.

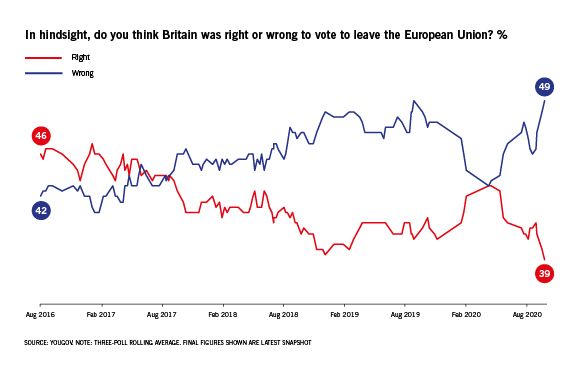

The third series displays a completely different pattern. Starting six weeks after the 2016 referendum, YouGov has regularly asked respondents: “In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the European Union?” Two things emerge from the series. First, the month-to-month fluctuations have been much less than the figures for salience or the government’s handling of Brexit. This right/wrong series may be coloured by people’s recollection of how they voted in 2016, when the referendum forced even those who had not previously cared strongly about Europe to crystallise whether, on balance, they were more for remaining or getting out. It may take something substantial to shift a voter into changing their mind on this, and as such this series is much less affected by short-term factors such as the news agenda, parliamentary turmoil and the state of negotiations. Secondly, however, while the change has been slow, the four-year trend has been of a very gradual, but cumulatively clear, drift to “wrong.” One reading would be that there has been a vague general sense that the process of leaving is more complex and messy than it might have sounded in advance. Three surveys in September and October indicate a ten-point lead for “wrong” (average 49 per cent) over “right” (39 per cent)—the biggest sustained rejection of Brexit since the referendum. Does this mean there is now a clear majority for reversing Brexit? No. Four polls this year, by BMG and Kantar, have asked whether the UK should rejoin the EU. In each poll, slightly more people have said it is better to stay out. Many voters now regret our divorce from the EU but are not (yet?) ready to contemplate re-marriage.

But could that change? Perhaps… and perhaps not. Until now, polls have been measuring public attitudes to a series of doubts and hypotheses. We might have our hopes and fears, but cannot be certain what life will be like when the transition phase ends and we face the full force of Brexit. The reality is yet to come, and may confound expectations. If we have learned anything from half a century of polling on Europe, it is that many people’s views are fluid and can shift fast if they turn against the politicians who are selling them a particular line, or come to suspect that relations with Europe are not being handled in a way that works for them. When we know what that reality is, and see its impact on our daily lives, polls will record the electorate’s verdict. What will that be? Ask me again a year from now.