In mid-October, there was an unusual book launch at the UK Supreme Court. In a crowded room at the top of a grand staircase, leading judges, advocates and legal commentators rubbed shoulders, sipped wine and enjoyed canapés, just as you’d expect. But among them were kids darting around the corridors. For the assembled jurists were not here to celebrate some legal treatise or academic tome but a children’s book. Equal to Everything: Judge Brenda and the Supreme Court by Afua Hirsch tells the story of Lady Hale, the court’s president from 2017 to January 2020, from her childhood in Yorkshire through to the legal profession and eventually the top of the highest court in the land.

Hirsch’s book will have struck a certain type of liberal parent as an ideal Christmas gift, but its real significance was in confirming the arrival of Britain’s first judicial superstar—a judge who is not only known and admired in the legal world, but who cuts a recognisable figure in the wider culture. In the United States, where the Supreme Court has the final say on huge social questions like abortion, there’s no clear line between law and politics. You can buy T-shirts showing the court’s liberal stalwart Ruth Bader Ginsburg with slogans such as “I dissent”—and, yes, a children’s book about “Notorious RBG.” On this side of the Atlantic, by contrast, on the rare occasions when the personality of a judge cuts through to public consciousness, it has normally been because of their archetypal judge-ish-ness—like, say, Jeremiah Harman, who claimed in 1990 that he had no idea what sport England footballer Paul Gascoigne played, and asked if “Gazza” didn’t feature in the title of an operetta. In ordinary times, no judge would have drawn the limelight in the way Hale did. But these are unusual times for the UK judiciary. And away from the cosy atmosphere in the court on that autumn evening, they are frightening times too.

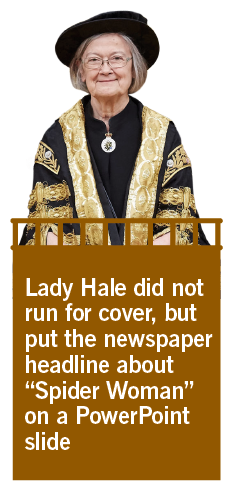

Recent rulings—above all the two so-called “Miller judgments” that punctuated the Brexit saga—have thrust the court and its judges to the centre of the national conversation. After the second of these cases culminated in Boris Johnson’s suspension of parliament being ruled “unlawful, void and of no effect” in September, Hale was suddenly a household name—her spider brooch became a social media icon. The judge did not run for cover, but instead put newspaper headlines about “Spider Woman” on to a PowerPoint slide during an address to a conference, and proudly reclaimed for herself Johnson’s disparaging description of David Cameron—“girly swot.” In late December—while still in post—Hale guest edited the Today programme, and took part in a head-to-head interview alongside Bader Ginsburg.

Although Hale retired as president early this year, the questions this sort of prominence raises for the decade-old Supreme Court and the wider judiciary are bound to weigh heavily on her successor, Lord Reed, her former deputy, and a cautious man whose instinct is likely to be to minimise controversy. Along with his promotion, three new justices will join the court’s bench this year. All will have to reckon with a thorny question: in a democracy, where the ultimate master is supposed to be the people, what should the chief umpire look like?

It is not only populists who worry about top judges stepping too far into the glare; plenty of lawyers and judges we spoke to worry that the Supreme Court has strayed from its proper position in our constitutional landscape. Even Charlie Falconer, the Labour lord chancellor responsible for the creation of the Supreme Court in 2009, told us that Hale “did… overplay her hand” by agreeing to do Today, adding: “I think that it would be better if she had nothing to do with what is the flagship political programme on the radio.” Meanwhile, the former master of the rolls, Lord Dyson, who also overlapped with Hale at the top court, and has previously spoken out against Tory ministers such as Chris Grayling, told Prospect: “maybe I shouldn’t say this but I will. I do think Brenda, who I’m extremely fond of and know very well, I think she’s beginning to see herself as a bit of a media star.” For her to, “while still in post,” start “talking about ‘girly swots,’ it’s not wise…” Lady Hale declined to respond to any of these criticisms.

Some of the concerns voiced about Hale’s approach are gendered—today’s judges and QCs grew up with an idea of a judge as a man, and simply by being a woman who has worked her way up to the very top, she has done something disruptive. There are, though, deeper questions to be asked about why Lady Hale—a usually reticent woman, who has confessed to “impostor syndrome”—has become a media favourite. Was it just the constitutional convulsions of Brexit, which should soon pass? Or has the interface between politics and the law become fraught for more enduring reasons? Is the court fated to rule on increasingly political questions, and—if so—can it hope to do so without becoming overtly political? Is it now impossible for the judges to sink back into splendid anonymity?

These are urgent questions as the court is under unprecedented attack. After the prorogation case, Johnson proclaimed blithely that the (unanimous) court had got it “wrong,” and his attorney general, Geoffrey Cox, floated the thought that “there may very well need to be parliamentary scrutiny of judicial appointments.” Meanwhile, the Queen’s Speech pushed forward with a “Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission,” which is plainly a vehicle designed to rein in what critics call “activist” judges. Could the notorious 2016 Daily Mail front page, which blasted three high court judges as “enemies of the people,” offer a foretaste of the agenda that a newly-populist government will pursue?

Previous record

It is possible we are getting ahead of ourselves in assuming any “reform” is merely an ugly power grab by the mop-topped Caesar in No 10. After all, “the people,” or at least the people “the people” elect, are meant to be in charge and the old caricature of the British constitution fitted comfortably with that. While judges were politically marginal, a government with a majority in parliament could do as it pleased because it was for the elected parliament alone to settle the law.

In truth, however, the supposed line between making the law and interpreting it has always been hazy. For example, it was not any Act of Parliament, but the ancient processes of the common law (judicial custom and precedent) that first defined the crime of murder in England. And since then, the intricacies of modern life and governance have inevitably made the line between writing the law and dispatching it even fuzzier. No statute, however well drafted, can deal with every contingency with which the modern regulatory state has to deal. And so we inevitably end up either with (potentially self-serving) ministers writing detailed regulations which parliament has no capacity to scrutinise, or else it falling to the judges to fill in the many blank or grey areas.

Generations before they became social media talking points, it was this deep logic—not any hunger for power—that was drawing the judges into politics and public policy. Over the last half century, three more specific developments embodied and reinforced the trend.

The first was the growth of judicial review of decisions by public authorities. As long ago as 1983, the recently-retired Lord Denning described this, and the associated development of a distinct “public law,” as a “revolution” in the British constitution. From at least the 1960s, more and more cases were brought and heard, and the judges reached for an expanding range of remedies. Legislation passed in 1981 (under the Thatcher government, it is worth today’s Conservatives noting) helped to formalise a shift that was already underway. The potential for clashes with politicians became clear in the 1990s, when right-wing ministers such as Michael Howard would often find their populist moves on immigrants, suspects or criminals being ruled against in the courts.

The second big—and related—change concerns human rights. The development of a “rights culture” since the early post-war world, with the UN Declaration and also the European Convention, gave judges new clout, especially after the UK enshrined the latter in the 1998 Human Rights Act. While the Act did not directly empower them to strike down primary legislation (passed by parliament), it greatly increased their ability to overturn secondary legislation and ministerial policy decisions. Where laws were ambiguous, the courts were now to interpret them in a way that protected basic rights, and if a statute unambiguously trampled on those rights, they could issue a declaration to prompt parliament to think again.

The third source of growing judicial power has been the inclusion of EU law in fields of European competence, such as workers’ rights and the environment. It has supremacy over UK law, meaning that where the two were in conflict, British judges could for the first time set aside laws that parliament had passed. This was probably true from the moment the UK joined the Common Market in 1973, although it was obscured until the 1990s, when Spanish fishermen, in the so-called “Factortame” cases, succeeded in getting a statute first suspended and ultimately disapplied as being contrary to European law.

Right now, however, the judges are vulnerable to actual or potential reversals on all three of these fronts. The UK will (supposedly) leave European law behind within months of leaving the EU; on human rights, the Conservative manifesto promised an “update” which very clearly means a weakening, since the express aim is to give the authorities more latitude in national security; and, on judicial review, the pre-election proposal was vague but described in loaded language—the overhaul was to ensure “that it is not abused to conduct politics by another means or to create needless delays.”

We were in a very different world when the lord chancellor (and former Tony Blair flatmate) Lord Falconer steered through the 2005 Constitutional Reform Act, which led to the creation of the Supreme Court four years later. The new court assumed the judicial role previously played by a very British anachronism—the so-called “law lords.” The role of the House of Lords as the country’s highest court stretched back 600 years, to a time before anyone had heard of the separation of powers, and for centuries the aristocrats who wrote the law saw no problem in second-guessing the courts who administered it by hearing appeals. Victorian reforms half-rationalised things, by specifying that the cases would at least be heard by an “appellate committee” of lordly lawyers and judges, but the law lords continued to meet in parliament, and remained free to vote on legislation if they wanted to, even if they often shunned that right.

Under the Falconer reforms, while the top judges kept their titles, they were finally prised off the red benches, and moved across Parliament Square to occupy the grand building at Little George Street: the legislative and judicial branches of the state at last became physically separate. More conservative jurists murmur that calling a court “supreme” was bound to make them too big for their boots, but Falconer tells us there was never any suggestion that the rebranding was about trying to make it the equivalent of its mighty American counterpart.

In the earliest days of the Republic, with the Marbury v Madison case of 1803, the US Supreme Court established its right to overturn any law that ran counter to the Constitution. Falconer would never have wanted the same in the UK, even it were an option: the price of the US court’s supremacy over Congress has been its independence. Judges are nominated by a president, then face confirmation hearings in front of a senate committee, two halves of a process that has become increasingly partisan. Already, by the time of the Bush v Gore ruling of 2000, which stopped the counting of ballots in Florida and thereby made George W Bush president, a clearly identifiable conservative bloc voted solidly for stopping the recount, while the court’s liberal minority voted equally solidly the other way. There is no use in pretending that it is anything other than a very political court.

For Falconer, the main point of his reform was not to establish the UK court’s “supremacy,” but rather to move in precisely the opposite direction of the US—by enshrining judicial independence. Until 2005, there was always the risk that the lord chancellor—a political appointee—would pack the bench with judges to his own taste. Falconer points to some of the controversial picks of Lord Hailsham, a right-wing lord chancellor in the 1970s and 80s, as cases in point. For the most part the temptation was not indulged. If the old system were still in place today, however, Johnson might have responded to his humiliation in Miller 2 by populating the bench with pliable jurists. By creating an independent Judicial Appointments Commission, and reducing the lord chancellor’s role to a limited veto, the 2005 Act at least removed this as an immediate danger.

But as the 2020s dawn, after decades of managing to have the best of both worlds—increased influence and increasing independence—Britain’s judges are suddenly vulnerable on both counts.

Case for the prosecution

Having traipsed into political battle late last year, a political pushback against the judges was probably inevitable. Any role for judges in politics is bound to be controversial. Might Johnson be justified in seeking a “reset” because (to use a phrase of the US liberal legal theorist Ronald Dworkin) “law’s Empire” has expanded too far? That was the argument made by the former Supreme Court justice, Jonathan Sumption, in his BBC Reith lectures in 2019.

In two recent cases, the Supreme Court has identified fundamental principles in our constitution, and then invoked these to make controversial rulings. Ordinarily, judges are very cautious about rulings that affect the public finances. But in the “Unison” case of 2017, they quashed the attempted introduction by then lord chancellor Chris Grayling of court fees in employment tribunals, by asserting the Rule of Law as fundamental.

“The true significance of the two Brexit rulings has been to emphasise that no politician, however eminent, is above the law”

At a push, the Rule of Law can be traced back to Magna Carta, and it has cropped up many times since—including in modern legislation. But it is often defined and discussed in vague terms. Here, however, the court found implicit in this general principle a presumption in favour of access to the courts—deciding that Grayling’s fees would frustrate this. (And for anyone assuming the Reed court will automatically be more deferential to the government than the Hale court, it is worth noting that the Unison judgment was written by Lord Reed himself.)

The second landmark case was the Miller 2 judgment on prorogation. Part of the reason Johnson lost was the court’s assertion that parliament’s job in holding the government to account was a fundamental plank of our democracy, and that it must therefore never be unreasonably thwarted in this task.

Few would dispute the court’s description of how British governance is meant to work, but while the judges were unanimous, broader legal opinion wasn’t—some lawyers and judges have indicated to Prospect that it is not for the court to try and crystallise the UK’s unwritten constitution. One lawyer involved with the Miller litigation refers contemptuously to the behaviour of the “lordships” and “ladyships,” who “preened themselves on their ‘historic’ role without really understanding… constitutional theory.” The judges, he continued, “illegitimately interposed [themselves] between parliament and the government,” with consequences that left him “fearful.”

Liberals might counter that the whole point of the ruling was to protect parliament by preventing the executive from exploiting crown privileges against it; but that reading didn’t impress one eminent former judge, who worried that the court had strayed too deep into “political matters.” And whenever judges do that, constitutional conservatives fret about undermining the principle of the 1688-9 Bill of Rights settlement, which holds that parliament must be free to run its own affairs without the courts getting involved.

Sumption himself agreed with the Miller 2 ruling, and tells us he has no problem with the court dealing “with the legal aspects of the constitution.” But he continued: “much of our constitution is not legal at all. It’s a matter of political convention. And I would certainly not wish it to enter into that field.” He worries a lot about judges “usurping the function of parliament.” There is something of the same sentiment in Lord Reed’s dissent in the Miller 1 case: “It is important for courts to understand that the legalisation of political issues is not always constitutionally appropriate, and may be fraught with risk, not least for the judiciary.” The new president himself, then, is keenly alert to the danger of the Supreme Court overreaching itself, and concerned it may already have done so.

Case for the defence

And yet most lawyers and judges, of whatever persuasion, are content with the broad direction the Supreme Court has taken. It is just not sustainable to suggest its first decade (see Raphael Hogarth’s selection of the court’s most memorable cases to date) has witnessed some sort of liberal takeover. On immigration, for example, it has often taken a restrictive view of the rights of foreign nationals. Even before the Supreme Court was up and running, in an emotive case concerning an HIV-positive Ugandan who had been kidnapped and raped, Lady Hale took a restrictive view of the entitlement to healthcare, reflecting that the duty to follow the law sometimes required judges to “harden our hearts.” Later, the court was extremely wary about pushing back against then home secretary Theresa May’s populist moves against “foreign criminals,” surprising many by allowing her to restrict interpretation of the right to family life.

And even with those controversial Brexit cases, more lawyers than not would agree with Lord Hope, the court’s former deputy president, that the real significance has been “to emphasise the fact that no politician, however eminent, is above the law.” Despite the backlash it provoked, the argument in Miller 1 really was a procedural one—triggering Article 50 would effectively invalidate a statute parliament had passed, the European Communities Act 1972, and hence it was incumbent on the government to seek parliament’s approval. Even in Miller 2, one reason the government was vulnerable was because it provided the court with no rationale for a prorogation that Johnson was half-pretending had nothing to do with Brexit—falling foul of the long-established public law principle that those in authority must act reasonably. The uncontrolled fury that followed, however, showed that reasonableness cannot be relied on with the current government.

Read Raphael Hogarth on six Supreme Court cases that hit the headlines

As Commons leader Jacob Rees-Mogg complained about a “constitutional coup,” Cox aired his thoughts about political vetting. While the attorney general qualified his words by airing some personal reservations, reports soon followed about other cabinet ministers agitating for this change.

For anyone concerned to see capricious power checked, the context is crucial. This is a populist age, and the independence of the courts is under assault in EU member states including Hungary, where the re-election of the sinister Viktor Orbán in 2018 attracted tweeted congratulations from Johnson. Closer to home, we have an administration that arrogantly presumes an entitlement to loyalty. During the election campaign, Channel 4 replaced a no-show Johnson at an environment debate with a melting ice sculpture, and days later there was muttering from No 10 about the broadcaster’s remit being reviewed. When the BBC shamed Johnson for ducking out of an interrogation with Andrew Neil, No 10 was within days asking questions about the future of the licence fee.

Against this backdrop, any constitutional “reforms” floated by this particular government are bound to risk being seen as about settling scores.

Sentenced to what?

But what, realistically, might the government actually do? One voice, especially, is worth listening to here. As first parliamentary counsel—the government’s chief draftsman—for six years from 2006, Stephen Laws was professionally tasked with ensuring that the law is written to do what ministers want. He remains a rare legal expert who empathises with ministers’ frustration with how the courts can hinder them in discharging what they regard as the will of the voters. He is now the brain behind the Judicial Power Project at the right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange, which has plans to allow ministers to take back control.

Talking to Prospect, he bemoans judges encouraging the pursuit of “politics by other means,” which is—tellingly—the same phrase deployed in the Conservative manifesto. “The final and most influential decision-maker on public policy,” he says, “must always be the one with democratic legitimacy”—not the judges but parliament, and the government it chooses to sustain.

“Some whisper that the Supreme Court should be renamed, and even returned to its medieval home in the Lords”

He makes that point in reasonable tones, and some of the suggestions in a recent Policy Exchange report on the judiciary, “Protecting the Constitution,” are, at first blush, incremental. On judicial review, rather than rushing in, they suggest reappraising its scope, then legislating to limit this only to the extent that it turns out to be necessary. On human rights, rather than immediately walking away from the European Convention, the suggested first step is to put forward a new protocol which allows states to “make reservations” to the interpretations of rights by Strasbourg. But dig into the plans, and harder edges emerge—for example, one fall-back plan turns out to be simply not complying with certain Strasbourg rulings.

Likewise, on the crunch question of judicial appointments, the tone is coy. Laws shrinks from outright support of parliamentary vetting, but tells us it is no surprise if there is a hankering for “more political control” over a judiciary which—despite there being several lay judicial appointment commissioners—he regards as looking unhealthily “self-selecting.” Policy Exchange proposes to bring a political touch to the appointments process by, first, making greater use of the lord chancellor’s limited existing power to say no to individual nominations, and then going further so that the commission becomes the shortlister, while the final choice about which judge to pick reverts to the lord chancellor.

It sounds like a small change, but if this power were granted and then used with determination, it could steadily entrench a big shift towards a model where judges were appointed in part for their views, as opposed to on merit alone. And this plays into a context where voices are suggesting that the Supreme Court should be renamed, and—unbelievably—even returned to its medieval home in the Lords.

Many judges may agree with Laws that their colleagues have “overreached” in particular fields, but however delicately couched the proposals may be, the idea of a more political appointments process is one that unites just about the whole bench, including its small-c conservative element. Hale herself was emphatic on Today: “We don’t want to be politicised.” Retired Court of Appeal judge Stephen Sedley warns that confirmation hearings would represent a “slippery slope… the first step towards the destruction of judicial independence.” Helen Mountfield, a QC and a leading legal mind, warns of judges ending up “beholden to the government which appointed them,” and even Sumption calls the suggestion “objectionable and useless.” Indeed, to anyone who witnessed ugly, partisan wrangling around the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee who faced multiple allegations of sexual misconduct, the very thought of getting politicians involved in judicial appointments brings a shudder.

Even if little comes of these plans, some liberal lawyers, including the Prospect contributor and anti-Brexit campaigner Jolyon Maugham, fear that mere talk of clipping judicial wings could do damage, by cowing the bench. Others, including Sumption, trust judges to stand their ground: “I know my colleagues pretty well. They are not going to back down because the government threatens them.” But if taking on the courts becomes the stuff of front pages, judges wouldn’t be human if they did not begin to look over their shoulders.

In summing up

For a decade the court has been “supreme” in name, but perhaps it was only last autumn that it forced Britain’s political class to take it seriously—by rapping the prime minister of the day over the knuckles. Now the PM is back with a mandate, and perhaps in a mood to demonstrate that under our constitution, no court—whether “supreme” or not—is ultimately equal to the power of a determined -government in possession of a pliant parliamentary majority. After a successful “people v the politicians” election campaign, a “people v the judges” pitch is surely a tempting next step. Unless Johnson ends up being distracted by other things, a bust-up is approaching and it looks set to be bruising for the judges.

And yet the looming fight is gratuitous. British judges, Hale very much included, are keenly aware that they operate in a system in which the elected politicians can, provided they do things by the book, get their own way in the end. For decades, our judges have risen quietly while always respecting this understanding, and thus made a more political place in the constitution without being seen as beholden to any political tribe. Even in the run-up to the prorogation case, the media did not second-guess whether individual judges were left or right, “activist” or deferential, or anything else as they would surely have done in the US. Instead, experts were brought into the studios to discuss what they thought the law actually was. Which is exactly the conversation you want, if the idea is independent judges dispassionately interpreting the law as they see it.

It is certainly on the judges to manage their public profile in a way that ensures this continues; and that will take more care than it used to, because the price of increased prominence is increased scrutiny. But it isn’t desirable to turn back the clock to a time when lawfulness barely intruded on public administration (see box below for the changing role of the attorney general), nor is it attractive to move into a future where the endlessly multiplying details of public policy are spelled out by ministers in long regulations which go through on the nod.

The truth is that to the extent that our Supreme Court has “meddled” in politics of late, it has not been to rein in politicians in general, but to defend democracy against an overbearing premier. The sovereignty of parliament is not in dispute, but it is perfectly compatible with the government being bound by the laws that it passes in the same way as everyone else.

The real threat to our democratic system comes not from “celebrity judges” making unusual rulings, but from an unruly executive that has shown unusual contempt for its norms. In his calculated vengeance, Johnson is fighting a phantom, and in the process undermining Britain’s hard-won reputation for judicial independence. This is not just a concern for judges but for everyone who cares about the rule of law—and the functioning, or otherwise, of our democracy.

Attorneys general and the lawful turn of politics

The rising power of the judiciary over the last half-century is only one aspect of a wider lawful turn in the culture of public affairs. To see it, consider the evolving role of the attorney general.

Four centuries after one former incumbent, Francis Bacon (pictured), described the post as “the painfullest task in the realm,” the agony of being pulled in different directions continues in a role whose duties include not only superintending the prosecuting authorities and providing rigorous legal advice to the government but also serving as a loyal minister whose hiring—and firing—depends on prime ministerial whim. Slowly but surely, however, the lawyerly duties have begun to weigh more heavily relative to the demands of political convenience, which used to trump them.

In 1956, Anthony Eden’s attorney, Reginald Manningham-Buller, advised that the invasion of Suez was unlawful but nonetheless stayed in and backed the government. By 2003, when another government was bent on military misadventure, this was not felt to be an option for his successor, Peter Goldsmith, however helpful he wanted to be. Instead, Goldsmith spent time with eccentric American lawyers so that he could cobble together an ingenuous argument that invading Iraq might be legal without express UN authorisation, in an opinion regarded as essential for keeping him and Tony Blair in office. By 2018-9, Attorney General Geoffrey Cox, Brexiteer though he is, was unwilling or unable to cook up a helpful interpretation of the Irish backstop that could have saved Theresa May’s bacon and her Brexit deal. He advised, first, that there was a legal risk of the UK being trapped, and then later that the political concessions his boss had secured had “not changed” this risk.

Before turning the clock back on what critics call “legalism,” it is surely worth pausing to ask whether we wish to revert to a time when the law was no check on driving dishonest policies through.

This article was amended on 27th January to make clear that while the Bush v Gore ruling divided the US Supreme Court’s liberals and conservatives, the two camps did not at this point entirely correspond to the party of the president who had appointed them