Electoral systems are a subject for nerds in very thick glasses—until the moment something goes wrong.

Before 2000, the “college” of elders that America’s founding fathers had imagined would wisely pick a president was a quaint anachronism. Its potential to turn a loser into a winner was of theoretical interest only, since it hadn’t happened in well over a century. Even when George W Bush triumphed with marginally fewer votes than Al Gore in that year, it looked like a fluke produced by the very close result.

Popularity plus

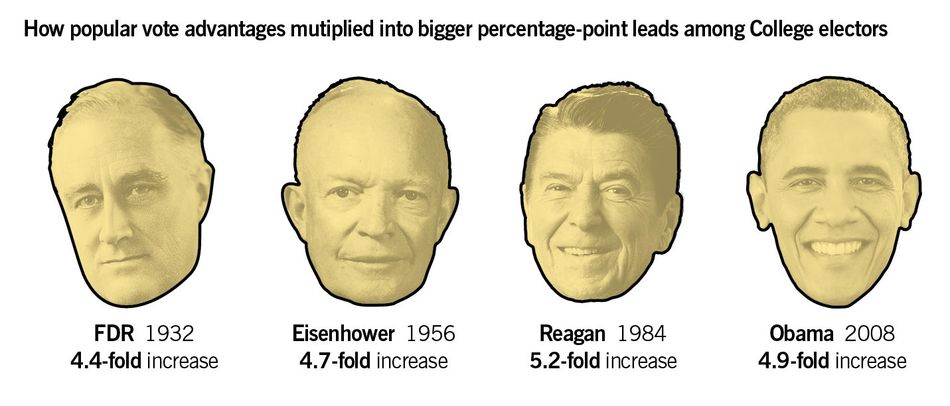

In all other modern elections, the College had worked to multiply the more popular candidates’ advantage several-fold, the only exceptions being three photo-finishes, two (1960, 1968) where leads of less than a point were magnified by more than you would have expected, and then 2000, when the process went into reverse. In general, typical leads (like 2008) and landslides (like 1984) were often multiplied in much the same way.

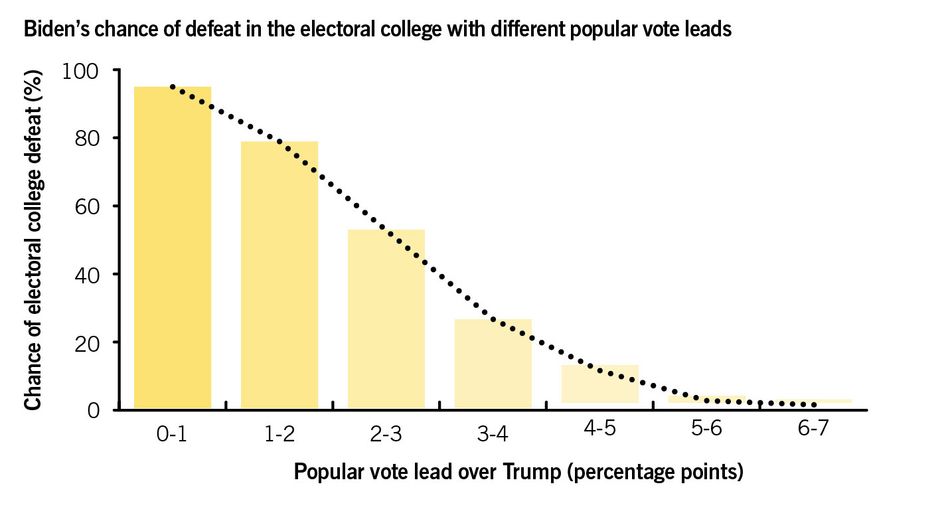

Losing by winning

In 2016, Hillary Clinton was the first candidate in well over a century to lose after winning the popular vote by more than one point. But this could become a pattern. Analyst Nate Silver’s numbers suggest that, even if Biden is a couple of points clear, the odds will be against him unless he reaches nothing short of a resounding lead. From here, it isn't hard to think that America’s shifting psephology has become a permanent handicap for the Democrats.

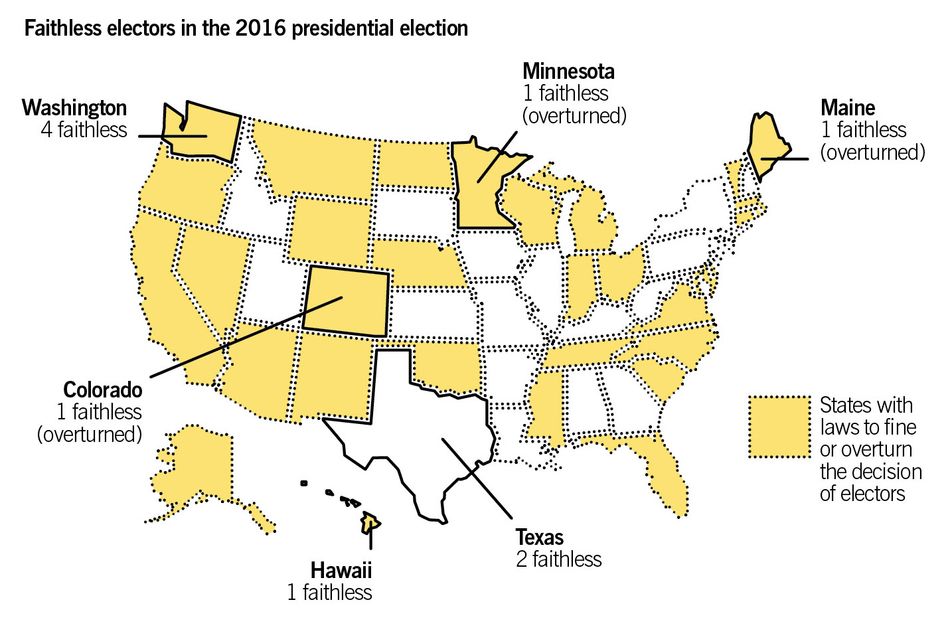

Faith no more

And if all of that weren’t explosive enough, nothing in the constitution obliges the 538 individual electors who make up the College to follow the popular vote in their state (though sometimes state laws do). In the century of elections before 2016, no more than one ever went rogue; but last time ten tried to go their own way, and seven succeeded. This time, amid expectations of chicanery, it’s time to don the thick glasses and swot up on those fusty old rules.