The opening scene of the latest Abba jukebox musical, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, is set in one of Oxford University’s ancient panelled dining halls. Lily James is, in flashback, the young Donna, graduating from New College (founded in 1379). In place of a speech she rips into a raunchy rendering of “When I Kissed the Teacher,” which soon has even the vice chancellor (Celia Imrie) casting off her inhibitions to join in.

The Oxford backdrop (a scene co-written by Richard Curtis, Christ Church) is entirely gratuitous. Donna’s Oxford education is irrelevant to the rest of the movie, which mainly takes place on the Aegean island of “Kalokairi.” But Oxford is—as in Inspector Morse or Brideshead Revisited—an internationally recognisable brand. It is the essence of England—as classic, in its own way, as Aston Martin or Burberry.

It also signifies exclusivity and elitism. Every year more than 18,000 young people apply to follow Donna through the ivy-clad doorways, but only 3,200 make it. Of these, just 2,600 live in the UK. In numerical terms, an Oxford education is always going to be for the few, not the many. The question of who gets to be among the small number of undergraduates admitted is a topic of ever-consuming interest—and, whatever the answer, some will likely see it as a symbol of unacceptable privilege.

A place at Oxford matters beyond symbolism. The badge of an Oxbridge degree will, on past form, take you far. Three quarters of our judges; nearly two thirds of our permanent secretaries; half our diplomats and newspaper columnists went to Oxford or Cambridge, along with a third of BBC executives; a quarter of all MPs, and nearly 40 per cent of the House of Lords. All compared with less than one per cent of the UK public as a whole. No wonder there is a long queue at the door.

But who gets through? The recent release of data on Oxford admissions pulled back the curtain on the choices individual colleges and faculties make, and fed familiar criticisms about the social and ethnic slant. One of the university’s most persistent critics, Tottenham MP and a former higher education minister David Lammy, bluntly summed up his view of the tables: “Oxford is a bastion of entrenched, wealthy, upper-class, white, southern privilege,” he tweeted in May. The university had to apologise after retweeting someone who described the MP as “bitter,” with its head of public affairs, Ceri Thomas, quick to signal a retreat: “We agree with you that Oxford needs to do more and criticism of us is no sign of bitterness.” That PR retreat is, perhaps, a sign that Oxford knows in its heart that there is a danger in simply dismissing the critics.

The mood of these post-financial crash times is, after all, a populist one. The financial resources of Oxford, or perhaps more precisely parts of Oxford, are envied by many universities. But for all universities—Oxford very much included—politics can soon impinge on the most critical sources of revenue, in relation to both research and teaching. The seeming independent financial security that many within the university sector felt they had achieved with the student fee-and-loans system today looks much less assured.

Last year, Labour snatched unlikely university seats such as Canterbury by vowing to abolish the scheme, and the Conservatives have since moved towards reviewing aspects of it. No university can afford to completely ignore what politicians or the voters think, and an elite university such as Oxford might do especially well to be sensitive to how it would, without reform, fare under a future Jeremy Corbyn government.

The complacent caricature

I write this piece wearing two hats. I’m a journalist with a lifetime’s experience on the outside, but I arrived in Oxford three years ago to become the head of one of the 33 undergraduate colleges, Lady Margaret Hall (LMH). Few people in any conversation about the English education system can claim to bring no baggage and perhaps I should acknowledge mine: an 11-plus failure who would have ended up at a secondary modern had my parents not made significant sacrifices to send me to what might be considered a middling private school. From there I made it to Cambridge, which I most certainly would not have done had I gone to the local secondary modern. In many ways I am a privileged person who has lived a privileged life.From the inside, I see real concern among many colleagues in numerous colleges to create a fair admissions system open to all. From the outside, I could see the frustration, even anger, at Oxford’s apparently glacial pace of change. To many within the university the system is—while not perfect—decent and uncorrupt. To many outside it is posh, snobby, unattainable. Bridging this gulf in perception is not easy.

Recent research for the university found the “toxic Oxford” image was entrenched in public perceptions. Focus groups around the country believed typical students to be white, disproportionately male and privately educated (estimates pitched the proportion as high as 95 per cent). Academic ability wasn’t thought to be enough to get in: people thought family connections or money were also needed.

In angry and anti-elitist times, this is a dangerous way to be seen. But most of these perceptions are inaccurate. In fact, more women than men received offers of a place at Oxford this year, and the figure for state-educated students receiving an offer last year was not 5 per cent but 58 per cent (and is above 60 per cent this year). As for those with minority ethnic backgrounds the proportion has been rising, at least when it comes to attracting applicants, and at nearly 18 per cent last year is now in line with the pack of Russell Group universities.

Some will use such numbers to dismiss the Lammy critique. But while it may be scattergun and trenchantly expressed, that critique does have some foundation. Until recently the Higher Education Statistics Authority (Hesa) placed Oxford at the bottom of all Russell Group universities in terms of admitting fewer disadvantaged and state school students. The university has regularly failed to meet a number of socio-economic targets it signed up to in 2009 with the Office for Fair Access (Offa).

Danny Dorling, a professor of geography at Oxford, claims the vast majority of the students Oxford admits are from the top 20 per cent of society. “We take almost entirely from the richest fifth of children,” he says, after studying Oxford’s own data, released after numerous freedom of information requests by Lammy and others, “and mostly from the best-off half of that richest fifth.” Dorling, who spends his life studying inequality (he is aware of the irony), is unsurprised: “I think Oxford admissions reflect the times. When the country is very unequal in other ways, the admissions statistics around disadvantage tend to be very poor.”

With my inside hat on, I sense a wish to move the needle—and some signs of movement. In researching this piece I spoke to many colleagues throughout the university who care passionately about admissions being fair, and being seen to be fair. The outside stereotype of the comfortably complacent don has been unfair for a long time; Dorling’s head of house at St Peter’s, former BBC executive Mark Damazer, suggests “the realisation that something had to be done was probably 30 years ago.” He insists: “A lot of imagination, money, effort, is thrown at it.” But he also concedes things moved only “slowly,” in a hit-and-miss manner: “nobody would accuse it of being brilliantly coordinated.”

But how to change? What to change? Money has indeed been thrown in the rough direction of the problem. Oxford spends around £17m a year on “access,” mostly financial support and “outreach” schemes to drum up applications. It organised 3,000 outreach activities last year involving more than 3,400 schools and colleges. And yet you can still read the student newspaper, Cherwell, claiming: “More students were admitted in 2017 from the top 12 independent schools than from all state comprehensives”… and find that this is not, as you thought it must be, simply fake news. In England, if we exclude the autonomous academies, there are 841 “state comprehensive schools.”

The missing 23

So how ambitious is Oxford being? Let’s take one of the four targets the university had agreed with Offa (now transferred to the Office for Students): to increase the number of candidates from Acorn postcodes 4 and 5, areas defined as “financially stretched” or regions of “urban adversity.” Let’s call students from these places “Acorns.”We must acknowledge that any statistical indicators of disadvantage will be imperfect, catching some who are privileged and missing others who face extraordinary barriers: certainly, that is true with postcode-based area measures, some of which have been found to wrongly “flag” students as disadvantaged as much as half of the time. Nonetheless, they tell us something. British black African applicants will, for instance, be more than twice as likely to be Acorns as others.

According to Oxford, around 20 per cent of all UK postcodes fall into this category of disadvantage, while around 15 per cent of the national pool of those who meet the minimum entry requirement (of three or more A levels at A grade) come from these areas. That means there is a possible pool of 5,000 Acorns with the minimum A level entry grades every year. But in 2015/16 only 220 Acorns ended up coming to Oxford.

That number used to be smaller, but not much. Back in 2009, Oxford set a “challenging” target of increasing the percentage of young Acorns from 6.5 per cent of its UK applicants to 9 per cent. In six out of eight years, it failed to meet that target. In practice, the Acorn count rose by an average of about 10 extra Acorns each year. Its new target, just half a point up on the old one, is to have 9.5 per cent of its 2,600 undergraduate entries be Acorns by 2019-20. How many more extra actual Acorns—real students—would that new percentage translate into? The answer is 23. Oxford wants 243 Acorns through the doors by 2019/20—just 23 up on the 220 it thinks of as a baseline. (Though, in fact, it exceeded that number in 2017, so even less progress would be required if Oxford took last year as the starting point).

Twenty three works out at less than one per college. To Oxford this is “challenging.” To Dorling “this is why people in the future will look back and laugh at us.” For comparison, Winchester College (£40,000 fees) sent 24 students to Oxford—about one in three of its Year 13 cohort—in 2017; St Paul’s (£37,719) sends nearly 40.

To be complete, Acorns are not the only group being targeted. But if you take all three of the disadvantage metrics used, and adjust to allow for those individual candidates who might be caught on more than one indicator, the ambition for increasing the total number of less advantaged students at Oxford by 2019/20 is just over 90—quite a bit less than the combined tally of, say, Eton and Westminster (104). It would, if achieved, work out at an additional three less-advantaged students per college.

A bleak sentence early on in a recent report overseen by the outgoing provost of Oriel, Moira Wallace cautions against any expectation of an early sea-change: “Progression to Oxford is… likely to become unattainable to many disadvantaged students because even Oxford’s minimum offer level... at A level, will be unachievable.” Some will see this as reason to give up on serious reform. Tests, they will argue, may not be a perfect metric, but they are the best measurement we have. Lowering the offer, says one senior tutor who spoke to me (anonymously), is “not in the universe of possible options.” “By the age of five, six or seven there is already a huge [attainment] gap. Oxford is spending vast sums on making very little progress. It is reaching practically all the candidates it could reach. It’s not going to change things by throwing more money at it. People are not interested in radical change.”

The obstacle course

Pause there and think about the gulf between someone from a comfortable home in a smarter part of town, and an aspiring Acorn who, despite all the obstacles in her way, still dreams of a place at Oxford. Here are just some of the barriers she will face compared with children from schools in leafier neighbourhoods (let alone the private sector). At GCSE level she is 27 per cent less likely to score five A* to C grades; there will be a similar pattern at A level. Her school is 70 per cent more likely to have high teacher turnover. This could affect her attainment, as will the fact that she is much less likely to have teachers with the relevant degree—say, in physics or maths.Her teachers could well be less likely to encourage her to apply to Oxford—and they will be less well placed to support her through the process. Then, she will probably have to sit one of the university’s aptitude tests, which could count for as much as 70 per cent of her eventual score for consideration during shortlisting. Her chances of being prepared for this hurdle at any state school will, on average, be half what they would be at an independent school. At a poorly-performing state school the chances will be considerably lower.

She will not have been able to afford extra-curricular activities or additional tuition (from £40 an hour with many private tutors to £1,995 to attend a privately-organised Oxbridge Preparation Weekend, including intensive coaching on admission tests and interviews). She may harbour doubts about whether she will fit in.

If she’s lucky enough to find a way to visit in the summer, she will find the streets lined with students fresh from exams but looking more like they’ve been to a high society function, the men in white tie with carnation button holes underneath their flapping gowns. (Cambridge, by contrast, did away with the requirement to wear gowns for exams as long ago as 1970). This could encourage fears that she’d be walking back into the 19th century, and perhaps doubts about how much the bizarre “uniform” might cost.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that she is statistically much less likely even to apply to Oxford than her contemporaries—14 per cent against 25 per cent of all A*A*A+ state school students and 37 per cent of such independent school pupils.

Oak trees might grow out of Acorns—and there is evidence that students who make it through from disadvantaged backgrounds eventually outperform their peers from better state, and independent, schools. But, as things presently stand, the cards are stacked against Acorns and other children who may be as “bright” as their contemporaries but don’t have the same start in life.

Many Oxfords

There is one view in Oxford that all this is a shame, but it is hardly the university’s fault. We might wish there was less inequality in the world. We might wish the schooling system was better—but it’s frankly not the job of Oxford University either to lower its standards in order to let in more disadvantaged children, or to become a kind of remedial school to make up the ground which should have been covered earlier. Oxford should go on doing what it does: it is for the government to do something about the dire circumstances which combine to defeat so many Acorns. This idea—that the real problem lies elsewhere—is commonly articulated.Trying to describe Oxford’s official view on what it thinks is not easy. There is a universally-agreed “common framework” which ties all colleges and faculties into a uniform system of admissions. In theory, there is one Oxford. But the tables released in May show that there is, in fact, a wide spread between colleges and departments in how that common framework is implemented (see box, left). There are, it seems, many Oxfords.

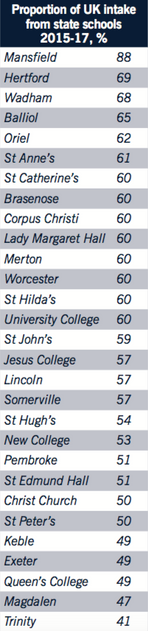

Mansfield College takes 88 per cent of its intake from state schools: for Trinity College the proportion is 41 per cent. Same system, but a gaping 47 percentage point variation in result. Computer sciences take nearly 78 per cent from state schools—a 40-point variance from theology and religion, and a 20-point difference with English. More than 12 per cent of St John’s College’s intake consists of Acorns; for Exeter College the figure is half that. (All figures here come from 2015 to 2017).

So the Common Framework allows for big variations in who actually comes to Oxford—which suggests that different colleges have contrasting reputations or policies. Mansfield, Wadham and Hertford, for instance, are known as state-school “friendly” colleges. It suggests, too, that the admissions system is interpreted and implemented differently from place to place.

Context is everything

Welcome to the shadowy world of algorithms, “flagging” and interviews. In most subjects, computers and aptitude tests come to the aid of tutors in winnowing down the 18,000-strong field to a number you can reasonably interview in a few days. A giant database called ADSS (Admissions Decisions Support System) contains most of the 18,000 names. ADSS will munch up candidates’ GCSE scores, predicted grades, aptitude test results, and even information from their personal statement, as well as their type of school and—in some subjects—an indication of whether a candidate has outperformed the average for her school. After everything is crunched, a single figure may also be generated, from 1 (bad) to 10 (good).It is all designed to be as “fair” as possible, and you hear many tutors across the university talking the language of fairness. “I just want a level playing field,” they will say. Or, “I don’t care where they come from, but I won’t stand for social engineering.” Paying up to £40,000 a year per child for the excellent education available at many private schools is not, it should be said, universally regarded as social engineering.

There is also a “flagging” system within ADSS, so that any tutor (and there are maybe more than a thousand across colleges and subjects) can assess and compare the “context” of a candidate, which might not be immediately apparent from the blunt computer-generated grade. A tutor might be tempted to interview only candidates within say, the top four scores—but should then (with varying degrees of enthusiasm, in practice) also keep an eye out for less well-graded pupils who have a “flag” for disadvantage of some sort. If a student is flagged there is firm encouragement to look at them carefully. But, beyond shortlisting, the question of how much weight gets attached to the flag becomes much less clear, and indeed the answer to it is much disputed.

Meet the admissions tutor from an august college (he prefers to remain anonymous) who is in no doubt that a flagged candidate will be given a leg up. “Other things being equal,” he tells me, “there is no evidence of prejudice against you if you’re flagged. The evidence is actually the other way. You are less likely to win a place from a private school.”

In fact, among those who get as far as applying, flagged candidates have a lower offer rate than private school pupils. There’s also still a small negative gap between the offer rate for Acorns and other candidates in general. Whatever work being flagged does, it wouldn’t appear to be enough to make up for the consequences of the reason you were flagged in the first place.

But confusion remains. When I first I arrived at Oxford, I sat in on a faculty “pooling” meeting where admissions tutors met to agree a cohort of candidates who could deserve a place but weren’t among the first choice of individual colleges. The 80-minute gathering grew tense as bitter disagreement emerged over how much attention to pay to the contextualised data at this late stage. One tutor spoke up for a flagged candidate who had failed to shine in interview; another vehemently disagreed with the drift of the conversation, calling it “embarrassing.” It was apparent that the admissions tutors had not agreed the ground rules before they met.

There are two points in the process where things get especially subjective—the interview, and whether to allow “grade forgiveness” once A level results are published.

Most of the admissions tutors and heads of house I spoke to defended the necessarily subjective interview process. Most believed tutors could spot the slick, glib student who had been coached within an inch of their lives and believed that, even if a candidate had not got the best grades, this was an important opportunity to show their ability to think.

I can testify that I personally know of a good many students at LMH who did not rank among the algorithmic “best,” but whose potential was nevertheless spotted by experienced tutors. The tutors derive the utmost satisfaction from watching them grow and—often—shine. Equally, choices can sometimes be frowned on by faculties that place great store by their algorithms; they will sometimes forthrightly challenge the acceptance of a candidate who is, on paper, weaker than others. They might argue this is “unfair,” or “risky.”

But language becomes confusing here. Is it necessarily more of a “risk”—or any less “fair”—to give a place to someone who is not highest-ranked but has overcome great obstacles in life than it is to save the place for someone else in the cohort with a higher score, but who hasn’t faced the same struggle to secure it?

Others again are sceptical that interviews can ever be used to unearth deep potential: “We try to make the distinction between people who have been well-taught and those who can make the imaginative leap,” says one doubting head of house. “That’s what tutors say they can do. Well, up to a point Lord Copper.”

As for grade forgiveness—showing clemency to students even if they fail to make their official A level grade offer—there is again a certain amount of haze. The university’s official position is that “students who have not managed to make their offer are rarely admitted unless there are extenuating circumstances.” In practice, around 160 students a year may be granted some form of clemency. MacDonald is frank about Wadham’s policy: “We admit sometimes 10, sometimes 15, sometimes 20 students a year out of 135 who don’t get their grades,” and “especially” in flagged cases. And, he goes on, “we’ve tracked them. They end up doing just as well.” But other colleges are more hesitant in showing post-A level clemency.

Marlborough man

Lurking somewhere behind the admissions debate in Oxford is what you might think of as the Marlborough factor—a reference to Marlborough College in Wiltshire (fees £37,815; seven Oxford places in 2017).Why Marlborough? The school’s name comes up as I am discussing the subject with another head of house—let’s call him Giles—and wondering what ways were open to the university to admit more Acorns. And not just Acorns—but more state school children; more ethnic minority candidates; more white working-class boys… and so on.

Giles is up for change—but says any new system has to be clear and defensible. He points to a recent letter in the Times in response to the data release. “My son, having achieved 12 A* grades at GCSE and three A grades at AS level,” it read, “was not even granted an interview despite being highly motivated. How much more academic brilliance is Oxford looking for? Or perhaps the fact that he was applying from one of England’s premier public schools (Marlborough College) might explain his exclusion.”

Giles furrows his brow. “You see, we have to tread carefully. It’s only a matter of time before the system is judicially reviewed. Its ability to behave sufficiently consistently across the piste will be exposed.”

So there’s the unspoken Marlborough factor: the anticipation that a litigious rejectee (or his parents) holds the system up to challenge on the grounds that Old Marlburians are the ones being discriminated against. It is a fear given extra charge by recent developments in America, where a case has been brought by a group of Asian Americans arguing that the “personal rating” system Harvard uses to rate candidates harms them—even as it helps applicants from other, more historically disadvantaged, minorities. They could soon prevail in the Supreme Court, with potentially huge repercussions for US affirmative action policies.

But Ken MacDonald of Wadham, who still practises as a QC, is unimpressed with the Marlborough factor. “I think a court would say that it’s within our margin of appreciation to make decisions of that sort based upon the knowledge that we have about particular candidates, and about the people with the highest potential... What we’re testing in the admissions process is not really achievement; what we’re testing is potential.” Perhaps the fear of litigation is a convenient one.

MacDonald continues: “In what sense is taking people from public schools massively, disproportionately not… a policy of discrimination?... If we test past achievement alone we disadvantage people from underrepresented backgrounds. If we test past achievement within the context of what we take to be potential, then it’s a very different story. And it’s obviously appropriate to do that.”

Nevertheless, the unspoken fear of Marlborough man lurks somewhere in the Oxford psyche.

Turning the tables

Within Oxford there are a variety of individual experiments—including University College’s pioneering bridging scheme and Pembroke College’s OxNet initiative—trying to find different solutions to pepper up the slow pace of change. And I’ll soon come to LMH’s own Foundation Year. At the same time, the university as a whole is expanding the UNIQ summer schools, which bring young people to Oxford for a week-long residential course. Change is in the air—and, even while writing this piece, there have been hints that the university knows that business as usual is not sufficient and that there is a willingness to think more radically. But putting it into practice will take co-ordination—not easy in devolved Oxford.As Mark Damazer notes, this federal university lacks a “supreme allied commander” who can impose transformation. Individual heads of house are themselves relatively powerless: the key decisions are in the hands of the countless (or at least uncounted) individual admissions tutors. Insofar as anyone might hope to pull it off, it might be Maggie Snowling, president of St John’s, who is about to become chair of the influential Admissions Committee and wants to improve coordination across Outreach as well as forging close relationships with teachers and creating better systems of evaluation. Why has change been so slow? “Well, I think conservatism,” she says. “I think there’s historically some tendency not to take risks around admissions.”

Again, we have that word “risk.” It cropped up time and again in conversations about aiming for a more diverse student body. The Norrington Table—the annual rankings of colleges by final degree result—is blamed by some as a very public league in which colleges (or their alumni) do not wish to be seen as “failing.” Take a “gamble” by departing from the traditional approach to picking “safe” students, and—some fear—your college may end up with fewer firsts, and slip down this league.

“Candidates can be high risk because you don’t know whether the fact that they haven’t got straight A*s everywhere is because of their background, or because they haven’t worked very hard, or because in the end they’re not actually going to make very good academic students of the kind we’re looking for in Oxford,” says Sam Howison, professor of maths.

“What we want are students with the potential to grow their mindset rather than sit where they are. But you don’t know, you can’t tell—they’re a higher risk.”

All the more so, he adds, in a devolved college system, where you might only be taking five or six students for your subjects, so every individual place is significant for you. He believes more centralised admissions could help to overcome the conservative approach to this risk.

With the new data release it is possible to test just how much “risk” is really involved. If you simply compare the raw Norrington with the proportion of Acorns, the first thing you notice is the absence of the inverse relationships which some of the traditionalists may fear. Yes, some of those colleges which draw heavily on the academically highly selective Winchesters and Westminsters, may do well on the former and poorly on the latter. But more interesting are the many other high-ranking colleges—such as Merton, St John’s and Balliol—that manage to be in the top flight on both the Norrington and the Acorn tables, giving lie to the idea that there is a necessary trade off. [Article continues after the table below]

____________________________________________________________

High table revisited

How to assess an Oxford college? Dons might bristle at the idea that its quality can be reduced to a single number, and ranked in a crude league table. And yet one such league does command attention, and inspire rivalry, each year. The so-called “Norrington table,” on the left below, is calculated on the basis of degree results, with more points given for firsts than upper seconds, and so on.

But the university is also signed up to targets that effectively make social mobility, as well as academic excellence, part of its purpose. Different measures can be used, but on the right we produce a league table of colleges ranked by the proportion of students from poorer postcodes.

While there is some shuffling between the two tables, what is striking are those colleges—St John’s, Merton and Balliol—which manage to hit the top 10 on both. Statistical analysis is under way at Oxford Student Union, which has found no connection between widening access on such measures, and final exam scores. Colleges can open their doors to previously excluded communities without fear that this will mean dumbing down.

____________________________________________________________

But the provisional work, based on last year’s numbers, suggests that there need not be any trade off between the two goals. “There is,” says Bertholdi-Saad, “no significant relationship” in colleges’s performance on the two scores. “The notion that expanding access is in tension with academic achievement does not seem to be borne out.”

Snowling is up for a conversation about more centralisation of admissions, as already happens in medicine. But she is aware of the likely resistance from some college tutors. Steve Rayner, Senior Tutor at Somerville College, articulates the traditional push-back: “I do like to feel that I’m not having students imposed on me from outside. It also does mean that the people making the decision are the people that are going to be teaching, in a very personal way, the people they select. This gives them a real stake in the decision.”

But mathematics professor Howison takes a different view: “I’m strongly in favour of it. College blind, centralised system—with interviews. If treated properly, the interviews provide a form of evidence that no other part of the process can provide.”

Meanwhile, one veteran head of house says wearily: “I have tried to propose a more centralised system and I have got no particular traction over several years.”

Change, if it comes, may be painfully slow.

Try something

Oter universities elsewhere in the world are trying a variety of radically different approaches. In the US, along with affirmative action policies, vast endowments of the Ivy League are often used to achieve “need-blind” admissions, so the decision about who merits the place is taken first, and split off from the costly business of working out who needs help with affraying the vast bills that would otherwise keep out everyone but the richest.For undergraduates in the UK, at least, the subsidised student loan system makes this less of an anxiety. And while we can and do envy the huge funds that flood in from American alumni, we don’t need to worry as much as about the suspected corollary—donors effectively “buying” places for their children.

Australian National University, on the basis of much research, decided on a model that has been used in Texas, Florida and California. It involves no interviews—the ANU will simply offer three places to the best-performing students at every school in the country. The university is also broadening its notion of extra-curricular activities. Being a family carer or having a part-time job will count as much as taking ballet classes or having done intriguing internships.

A similar scheme in the UK would mean a comprehensive in Hartlepool would, alongside London’s top grammar school, and indeed Eton or Westminster, be offered three places in the first instance. There would then be further places offered to students in the top ten per cent of performers, in which the likes of Eton and Westminster would probably still be over-represented. Deputy vice chancellor, Marnie Hughes-Warrington, accepts that only a minority of offers made to poorer areas will be taken up, but still insists they are worth making: “We’re the national university, we’ve got an obligation to serve the nation.”

Oxford is, perhaps, more likely to be judged against its peers at home. But here, too, some radical ideas are being developed. At King’s College, London there is a powerful, well-resourced and 15-strong access operation run by a Doncaster-born former Oxford outreach officer, Anne-Marie Canning, whose energy was acknowledged by the award of an MBE at the tender age of 32.

This Russell Group university has the fastest-growing population of low-income students: its intake is 77 per cent state school and 48 per cent minority ethnic. It has built up a free, structured two-year widening participation programme—named “K+”—open to year 12 state school students with parents who did not go to university.

Students who take part in the K+ programme may get a “variable offer” of up to two grades lower than the “standard” offer. Unlike what she calls “drive-by” or “spray and pray” outreach schemes, this one hardwires access into the admissions process. Once a student has enrolled in K+ and has been made an offer it requires Canning’s sign-off for that student not to be accepted.

And the ancient rival, Cambridge, which has tended to do better on state school admissions than Oxford since the late 1980s, is also moving again, and is reported to be planning a foundation year in the footsteps of Trinity College Dublin’s programme. Sam Lucy, an admissions tutor at Newnham College, Cambridge told the Financial Times in June that her university intended to introduce a fully funded year-long course for academically able students from underrepresented backgrounds by 2020. “We want it to be university wide,” she told the FT, “with all of the colleges showing a collective front.”

At LMH we were also inspired by the programme at Trinity College Dublin for taking disadvantaged students for a year—along with that institution’s 20 years of data, which shows how those who’ve been through the scheme have performed as well as other students over time. Working with charities we promote the availability of the scheme to young people, we offer a way into Oxford in return for lower A level grades than the university’s standard requirement, although only after seeing hard evidence of them coming from a home of modest means.

We pick from among them using a range of methods designed to spot potential rather than pre-existing achievement; and provide them with a bespoke tuition, with an opportunity, after the year, to apply to transfer into the first-year undergraduate programme.

Out of our own two first cohorts of 21 students, 16 have gone on to be full Oxford undergraduates. LMH is already looking, and feeling, different with the presence of these bright and resourceful students. The pilot scheme is currently funded by LMH alumni (including a banker and a US department store boss) who wish to give something back to a university which, in a different era, enabled them to grow and prosper, regardless of their own modest personal backgrounds.

The scheme has admirers in Oxford—though other colleges are currently officially discouraged from following suit. Others claim it is an expensive way of finding under-represented students and bringing them to Oxford. The Foundation Year for 12 students costs around £230,000, which includes all teaching, support and accommodation. The budget for the college would be considerably lower if students could benefit from the bursaries and other financial support available to low-income undergraduates at the university.

Besides, critics who use the cost argument must engage with the unimpressive record of current arrangements. Recall that between 2009 and 2016 the university managed to add fewer than 10 extra Acorns annually, despite the Offa-declared annual spending (outreach and financial support) of £14m.

A colleague crunching her way through Oxford’s data calculates the “cost of acquisition” for every additional student from poorer postcodes (on any definition) since 2009 is in the region of £108,000 (126 extra disadvantaged students for an additional £13.6m in outreach spending). That’s roughly three full-time outreach officers for one low-income student.

But is a foundation year an easy back-door into Oxford? I doubt any of the students who have done the course would say so. They have three solid terms of essays, assessments, tutorials and tests. That is a much more challenging gauntlet to run than the standard “front door” test and interview process.

The perils of passivity

Why should Oxford want to change, though? The 18,000-long queue at the door will, if anything, grow over time. The arguments for not altering course very much are plausible and tempting: the university must never “drop its standards.” It’s for others to deal with the social engineering that results in the “best” candidates coming from such a limited socio-economic pool. We should continue to provide a world-beating education to the most talented.But a university that remained little changed would hardly shift the “toxic Oxford” perception revealed in its own research—a perception that self-reinforces by discouraging applications from people who don’t believe Oxford is “for them.” Does that matter? I think it does—partly out of pure self-interest, partly out of what Maggie Snowling of St John’s describes as a “moral imperative.”

The self-interest includes the fact that, as things stand, Oxford is undeniably missing out on talent. It rightly wants to recruit “the best” but it is struggling to find them all—unless you believe “the best” uniquely reside within the top 20 per cent band of the socio-economically better off.

MacDonald is convinced that this imperative should win through on both academic and public policy grounds: “We’re talking about having the most fairly assembled and rationally assembled student body that we can achieve. And that is not achieved simply by taking people who come through the system each year with top marks. Because if we do that, then we’re excluding what seems to me very large numbers of brilliant young people.”

Some academics are—still—suspicious of “diversity” arguments, imagining them to be born out of political correctness. They seem unaware of the almost universal trends in society towards widening pools of recruitment. The judiciary and the bar do not want to go on being dominated by (what are widely perceived as) white, male, public school-educated Oxbridge stereotypes.

Nor do the City, corporate boardrooms, the intelligence services, the army, the media, the cultural world, politics, the foreign office, Whitehall or the medical professions. They want to change and are casting around for the best channels to find the best and most diverse group of lawyers, soldiers, doctors, CEOs, politicians, actors and editors of the future.

If Oxford shrugs—“we can’t find them either!”—and blames a failing school system, it will look to some as if it’s failing in its wider social, educational and charitable purposes. Those who remain unpersuaded might reflect on the drip-drip of criticism from politicians across the spectrum, along with think tanks and, importantly, the regulators who ultimately determine the fees that universities can charge.

See the attacks that rained down on Oxford’s head from the last Conservative administration—including David Cameron (Eton, Brasenose) and higher education minister Jo Johnson (Eton, Balliol)—and imagine how a Corbyn government might behave.

Even the current universities minister, Sam Gyimah (Somerville), used the word “staggering” to describe Oxford and Cambridge’s current record. And then there is the recent financial threat from Michael Barber (Queen’s College), Chair of the Office for Students, warning that he would use his powers to reduce the tuition fees cap from £9,000 to £6,000 for any university not increasing its intake of students from diverse backgrounds.

But there’s a different kind of self-interest, well-articulated by Harvard in a description of its conviction that “diversity adds an essential ingredient to the education process” submitted in a Supreme Court case in 1978: “If scholarly excellence were the sole or even predominant criterion, Harvard College would lose a great deal of its vitality and intellectual excellence and … the quality of the educational experience offered to all students would suffer.”

And there’s the final thing: unless Oxford changes, it will be doing no favour to future graduates, for whom an Oxford education could increasingly be perceived as a signifier of social background as much as academic ability.

The university is, famously, a collection of self-governing communities. They are its glory and its strength. They are the reason the university has survived and thrived for the best part of 900 years. But the modern world moves with unforgiving speed and an inability to change fast enough could leave Oxford looking quite exposed. Finding another 23 students from the wrong side of the tracks may not cut it.