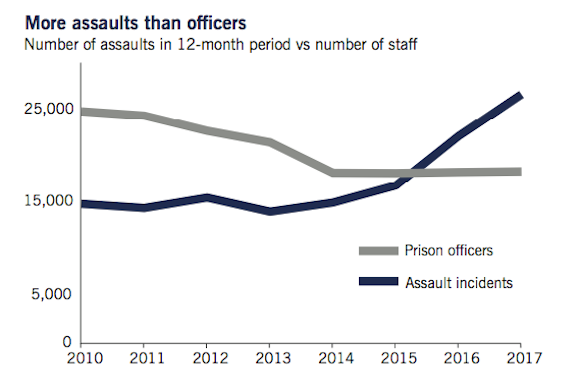

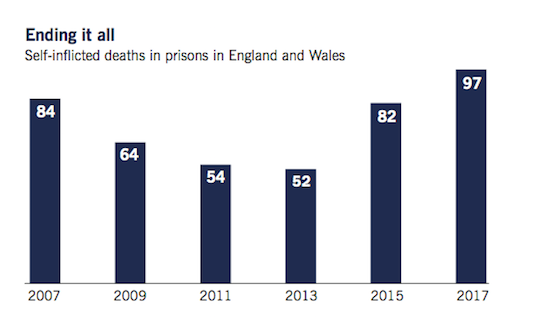

Words are no longer adequate to discuss the simmering conditions inside our prisons, so let’s try a few numbers. In 2010, 58 prisoners in England and Wales killed themselves. Last year, the number was 199—that’s an increase from about one suicide a week to approaching four. Suicide, of course, is only ever the tip of an iceberg of misery. In 2010, there were 26,979 recorded incidents of self-harm; last year there were over 40,000. And what about violence that turns outwards instead of in? In 2010, there were 2,848 recorded assaults on prison staff and 11,244 inmate-on-inmate assaults. Last year those numbers were 6,844 and 19,088 respectively.

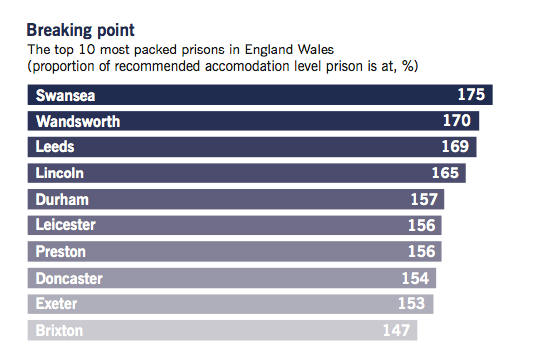

In 2015-16 almost 21,000 prisoners were held in overcrowded accommodation, many doubling up in cells designed for one. In some prisons, the ratio of prisoners to staff officers is as high as 30:1—fully three times the level of staffing that many of the experts suggest is wise. The output of this brutal, broken system remains stubbornly unreformed. Forty-four per cent of adults are reconvicted within one year, and that figure rises to 59 per cent for those serving futile short spells. Heaven knows what it would rise to if we were able to include all those who reoffend but don’t get caught.

Every available statistic shows a system that is inexorably lurching from chronic failure towards acute crisis. This autumn, 10 groups of anti-riot officers were sent to Long Lartin prison in Worcestershire after 80 prisoners took over a maximum security wing housing some of the most violent offenders in the country. That came almost a year after a riot at Birmingham’s main prison, when armed police were posted outside in case inmates escaped. One former prisoner told me starkly where all this is headed: “We are going to have major prison riots in which people will die,” he said. “Officers will be taken hostage, tortured and murdered. It’s going to happen.”

Here, Venetia Rainey looks at how the Dutch solved their own prisons crisis

This diabolical pass has been reached in a fast-ageing society that is a good deal more law abiding than it was a generation ago. So how on Earth did we get here? There are two halves to the answer—a slow story of rising recourse to custody over many decades, and a much more recent tale of scrambling to meet the vast demand with reduced resources.

We gradually refrained from the routine of thrashing and killing criminals over the 19th century, and the impulse to lock up ever-more citizens did not kick in for a while. During the first half of the 20th century, the prison population was broadly stable; during the interwar years it actually fell. As late as the mid-1950s, the total prison population was just 20,000. It is now over four times larger. But the use of prison began to pick up in that post-war period. That may seem like an oddity, since these were years of full employment, times when most young men had spent time in the army, and the rate of crime was both low and stable.

But then the number of offences committed has never had much direct connection to how many people get jailed. There was an upward drift in the number through the low-crime 1960s, the rising crime 1970s and the high crime 1980s alike, although this slowed for a time in the late 80s thanks to the efforts of Douglas Hurd, Margaret Thatcher’s liberal Home Secretary. As late as the early 1990s, a time at which the official estimates suggest there were roughly three times as many offences committed as there are now, the prison population was still only around 40,000, or about half what it is today.

But suddenly, in 1993, the incarceration rate began to jump up much more sharply. Moral panic set in during the aftermath of the killing of two-year-old James Bulger, an appalling but freak incident which the ambitious young Shadow Home Secretary, Tony Blair, seized on as if it were a symptom of moral decay across the nation. Not to be outdone, the actual Home Secretary, Michael Howard, pronounced at that autumn’s Conservative conference that “prison works.” The Hurd-era hopes of turning jails into places of reform were forgotten, and the message—which magistrates and Crown Court judges soon began to heed—went out that patience had snapped, and the requirement now was simply to bang more people up.

At about this time, in Britain as across the western world, crime did begin to fall. There were a host of reasons why, from the reduction of unemployment in the economic upswing, to the arrival of cheap manufactures from China, which depressed the second-hand value of stolen goods, to a host of technical developments that have made some types of crime harder to commit— improvements in car locks, immobilisers and the increasing prevalence of CCTV, for example. There must, undeniably, have been a certain “containment effect” from the rising prison population—the fact that inmates can’t commit crime outside prison, during the often-short period they are inside—but it is equally undeniable, that this must have been very small.

“Labour offered an almost seamless continuity with its Tory predecessors”As a matter of arithmetic, there are simply too many crimes, and too few people in prison at any one time for the growing prison population to move crime rates materially. Jail could only be truly effective if the threat of it discouraged potential criminals, which is a contentious claim at best, or if time served made people less likely to offend again—something those reliably appalling published recidivism rates demonstrated they did not do. Howard, however, was not going to let any of this get in his way. In April 1997, just a few weeks before the election that made Blair prime minister, the prison population reached 60,000 and Howard remarked that: “It is no coincidence that recorded crime has fallen by record amounts over the last four years, at the same time the prison population has risen.” “Locking up” criminals, he ploughed on with a wilful lack of argument or qualification, “stops them committing further crimes.”

In 1997, New Labour famously promised to be “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime.” The genius of that slogan was that people heard what they wanted to hear—liberals thought they were being offered a promise of reform, social conservatives a doubling down on Howard’s get-tough tactics. In reality, Labour offered an almost seamless continuity with its Tory predecessors—the number of people behind bars continued to rise, and at much the same rate. By the time Labour left office in 2010, the prison population had risen by almost 50 per cent to 88,000. Improvements in forensic science increased conviction rates during this period, but new legislation—including minimum sentencing for some eye-catching crimes—and the creation of over 3,000 new criminal offences were also contributing factors.

It wasn’t meant to be this way. Most Labour home secretaries would talk a mix of the tough and the tender, promising to match longer sentences for the more serious crimes with more discriminating use of prison and better rehabilitation programmes. None of it happened. The stampede towards longer sentences, and the commensurate need to build more cells, simply consumed too much attention and resources to allow room for more imaginative schemes. Labour left office locked up in failed thinking.

If the Blair/Brown years ended up being marked by a steep rise in prison numbers, the last seven years of Conservative government—with Liberal Democrat assistance during the coalition years—have instead been defined by drift, indecision and austerity. With five justice secretaries in seven years—three in the last two years alone—the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) has bumbled its way towards the current crisis.

It’s easy to forget now, but when the self-styled “coalition of liberty” came to power in 2010, reformers briefly hoped change was in the air. When the liberal Kenneth Clarke became Justice Secretary in 2010 he made the most serious push against mass incarceration of any minister since Hurd, not merely talking up the greater use of community sentences, but publishing a target to reduce the jail population by 3,000 through a specific list of measures to curb prison sentence inflation, including a proposal for enhanced discounts for criminals who entered an early guilty plea. Within a year, however, a retreat was under way, after Clarke sparked a huge row by talking about “serious” rapes in a manner which suggested others were less than serious, and as his Labour shadow Yvette Cooper called for his head, David Cameron panicked about looking soft on crime, and effectively scrapped the plan.

Before long he was replaced by Chris Grayling, a right-winger who had in opposition called on the police to develop a 21st century “clip around the ear” to bring unruly youngsters to heel. In office he was forced to find £2bn of cuts without the help of Clarke’s reduction in the numbers. He relied on “payment by results” and “benchmarking” schemes, which in practice accelerated the shift towards private prisons and sent a shockwave of cost-cutting through the prison estate, a wave that continues to this day.

But in 2015, when Michael Gove was shuffled from Education to Justice, the department got another liberal reformer. He won praise for his honesty about the failings of prisons, and for opening them up to the media. When I spoke to Gove, he told me that getting the public onside was key to how he wanted to tackle the system’s issues. “We wanted to make people aware of the problems we face in prisons. It’s far better that people have a mature understanding that prisons are not working in the way they are meant to.”

But in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, the Cameron cabinet descended into Reservoir Dogs, with Gove as one of the highest-profile casualties. In his place came Elizabeth Truss, who made more liberal noises about turning “offender warehouses” into “disciplined and purposeful centres of reform where all prisoners get a second chance at leading a good life,” but lasted just 11 months before Theresa May’s snap election. She was then shuffled out, and her successor—David Lidington—has been all but silent as the prison crisis deepens, perhaps because he is distracted by the considerable challenge of extricating the legal system from the EU, a challenge whose intricacies he will be all too familiar with, having been Minister for Europe under Cameron.

So where have we been carried by this conveyor belt of ministers? To a place so bad, it can no longer be disguised. This year, the prisons minister, Sam Gyimah, who has been in place since July 2016, effectively conceded that safety had become inadequate, and that this was preventing inmates from being reformed. He said: “If you have a safe environment then you have the preconditions to begin to reform prisoners and cut re-offending.”

Prisons remain, as always, a social dustbin that has to accommodate all of society’s latest problems. Presently, there is for example a pressing problem with drugs. The availability of cannabis, cocaine and heroin have been reduced by search methods, but new substances and “legal highs,” have proven trickier to deal with. One legal high is a form of synthetic cannabis called spice, which has flooded the system. A 2017 BBC Panorama documentary focusing on Northumberland’s main prison, operated by Sodexo, showed one inmate threatening to attack an officer with furniture and another officer convulsing on the floor having inhaled spice that was being smoked by prisoners. Such horror stories are backed by statistics. Data from the inspectorate of prisons shows that in 2010, an average of 24 per cent of inmates per prison agreed that it was easy to get drugs of any sort. The figure for 2016 is 46 per cent.

The deeper problem, however—and the one that prevents issues like drugs being grasped—is the extraordinary depth of the budget cuts. Unloved and invisible, prisons have never been shielded from the spending axe. By 2017, the real-terms prison budget was 22 per cent lower than it had been in 2010. Cuts on that scale can’t be achieved by “efficiencies”—the service has had to pare back on its big outlays, above all staff.

Years on end of a 1 per cent pay cap have sapped morale to such an extent that this autumn ministers buckled and named prison officers as one of the professions which would be allowed a (very slightly) higher settlement next year. They have been forced to recognise that low spirits among the staff who remain is a dangerous problem because so many jobs have gone. The number of frontline public-sector prison staff is now down by 26 per cent in seven years, a decline that has bitten just as hard in high-security prisons. Indeed Belmarsh, which has inmates including Islamist preacher Anjem Choudary and serial killer Stephen Port, has experienced a drop of almost 40 per cent. The prison service lost a large number of experienced staff with lengthy careers—the worst people for a prison to lose, but the best for the budget. A wave of young and inexperienced staff came in to replace them. The balance of power in prisons shifted from the officers and staff to the inmates.

John Attard from the Prison Governors’ Association told me just how badly this warps the relationship between officers and inmates on the wing. In a well-run prison, “It’s about conversations with prisoners that have built up over time,” he said. “Because you’ve got a relationship with that prisoner... he or she is likely to tell you [about] something that [could] disturb the balance of the prison.” But now, with inmates as numerous as ever and vastly outnumbering a new intake of inexperienced staff, there is no room for any of that. Order is breaking down. An especially nasty trend, Attard told me, is for boiling water mixed with sugar to be thrown in an officer’s face—the sugar makes the boiling mixture stick, and injuries more severe.

The remorseless cutbacks have forced recourse to some managerial wheezes which are only aggravating the situation. For example, there is a tendency to increase reliance on private prisons. They have been a controversial feature of the system for a generation. In some times and places, they have won some admirers among progressives, for doing things differently and loosening what used to be seen as the excessive and brutal grip of Prison Officers’ Association lifers. But part of the attraction to government has, undoubtedly, always also been to make deep savings on wages and pensions costs. By hiring from outside the service and its strong union, the likes of G4S save £5,000-£8,000 per officer on basic salary, and more when the full range of terms and conditions is allowed for.

Grayling, a particular fan of privatisation, cited Oakwood, a private prison near Wolverhampton as an inspiration. It opened in 2012 with a running cost of around £15,500 per prisoner, 31 per cent less than the public-sector equivalent. Grayling’s brainwave was that public-sector sites should simply reduce their costs using an equivalent private-sector prison as a “benchmark.” They began to do so, and the effect has been to bring to the surface many of the problems that had until then been bubbling away, with all the grim consequences that I have described.

The contracts themselves are, of course, also lucrative to those who land them—worth £4bn to the three main operators G4S, Serco and Sodexo. But the less well-paid and less experienced staff have found it hard to stay in control. The government’s performance tables have often shown private prisons over-represented in the bottom quartile.

All of this penny-pinching has gone on without any reflection about the root cause of Britain’s outsize prison bill. The number of people incarcerated in England and Wales is the highest per capita in western Europe—almost 150 prisoners per 100,000 population. A more rational approach to getting better value-for-money would start by interrogating what we hope to get out of the multiple billions that this continues to cost the taxpayer.

In a world where prison capacity is never enough, over-crowding is bound to be chronic, and the scope for rehabilitation sorely compromised. The system has been overcrowded every year since 1994 and some prisons are today operating at 190 per cent capacity. There is no room to do more than keep inmates alive in such circumstances, and when you throw in the effect of increasingly casualised staff you begin to see why talk of rehabilitation comes to nothing, and also begin to understand those appalling recidivism rates. Even in narrow economic terms, the burden of this is enormous: the National Audit Office estimates that re-offending costs between £9bn and £13bn annually—three quarters of that is down to people who had served short sentences, who will be back on the streets in no time. In social terms, what this means is that the public is simply not getting the protection it is paying for.

Intermittently politicians express concern about the futility of disruptive short prison spells, but they cannot resist using them to “send signals.” In 2016, 68,000 people were sent to prison to serve a sentence—almost half (47 per cent) were sentenced to six months or less. In parallel, the use of community sentences has nearly halved since 2006, despite strong evidence showing that they are a more effective deterrent.

At the other end of the scale, once-rare jail terms of 10 years or more have also become far more prevalent, the number increasing by 250 per cent between 2006 and 2016. It’s always hard to argue against being tough on serious crimes, but the effect of this is to unleash sentence inflation right the way down. And the result is a feedback loop in which offenders are sent to failing jails and on release are likely to reoffend, to return to prison and so on. The stress on the system is building ominously.

“More musical chairs at the MoJ all but guarantees the continuation of the crisis”Even as the situation in prisons becomes ever-more critical, a government consumed by the policy and political problems of Brexit becomes ever-less capable of committing the necessary time, capacity, attention and money that the system needs. No new additional funds were forthcoming at the most recent Budget delivered in November, meaning the real terms cuts made to the MoJ’s budget since 2009-10 are staying put. It means that the door currently blocking progress is likely to remain shut—after all, very little is going to be accomplished without real investment or a decrease in the number of people going to prison in the first place.

But that is not to say that solutions can’t be discussed. They should be. Urgently. The first step is to appoint a reforming Justice Secretary, and give him or her enough time to make things happen. More musical chairs at the MoJ all but guarantees the continuation of the crisis. If real progress is to be made, that reforming justice secretary will have to defend their budget, but also battle the pressures on it. At root, that means being plain that some sentences have got too long, indeed that in some cases, pushing for the replacement of jail terms with community sentences. Very specifically, it will mean cutting right back on the number of prison sentences of 12 months or less, which offer the public no sustained protection, but leave the offender with a black mark which makes it harder to get work or land secure housing, dramatically increasing the chances of entering the cycle of re-offending.

Such ambitions will not be easy to achieve. The media is, of course, especially sensitive to any hint of an overly-lenient criminal justice system. But if this Justice Secretary is able to get the support of fellow MPs and the public to reset the community sentence programme, overcrowding will ease and the atmosphere will improve for both inmates and staff. With fewer people behind bars, the pressure on staff will be reduced.

But let’s not forget that the alternative is fraught with risk too—including financial risk. MoJ figures suggest that over a quarter of frontline staff quit within two years. Only when the outward flow of staff is stemmed, and the inflow of prisoners is slowed, will it be possible to restore prisons to any sort of sustainable equilibrium. To get them, in other words, into the sort of condition where they can provide the relationships, the space for reflection and the training which really can rehabilitate, and allow them to be more than an expensive way of making bad people worse.

As things stand, fear is endemic among inmates and among staff, and lives are being lost. It’s mostly happening out of sight, but soon enough a riot or some other catastrophic crisis will push this emergency into plain view. Although the solutions are clear, a drifting and divided government appears unable to unlock them.