If you asked me what I learned in my public education about Roma and Sinti genocide during the Holocaust, it would be a lie to tell you I was taught nothing. I remember it vividly in my Texas high school World History textbook, the small footnote that included Roma and Sinti victims as an asterisk, a tacked-on fact that labelled us “gypsies” with a lower-cased G. There was no further explanation. Omitted from the main narrative, it would have been easy for anyone to miss. Nevertheless, as a Roma woman, it was the first time I saw any non-Roma media mention it. I would soon learn those small moments of inclusion are few and far between. That memory would become the status quo for how to feel on the historical silencing of Romani oppression: be happy with what you get; they could have not included you at all.

When many people think of the Holocaust, they often recall it as primarily a Jewish genocide, perhaps with some awareness of the oppression of other groups such as disabled people. The Encyclopedia Britannica, for instance, takes care to contextualise the systemic murder of the six million—but while it adds that “millions of others” were also killed, its consideration of Nazi racism is limited to anti-semitism. In reality, the racist ideology of the Nazis extended to Roma and Sinti people (known as Zigeuner in German or “Gypsies” in English) as well as the black European population. The total number of Roma and Sinti victims of the Holocaust remain unknown, with scholars and activists claiming anywhere from 200,000—a conservatively estimate, widely debunked given how many countries were occupied—to as high as 2 million.

We do know some statistics, however. We know for instance that in some countries, like former Czechoslovakia, 90 per cent of the Roma and Sinti population were murdered, wiping out whole cultural traditions and dialects. While Romani rights activists and Roma and Sinti survivors of the Holocaust have implored for more representation as well as reparations, their work has often been ignored by government officials and Holocaust museum boards. It’s almost like some would like the world to forget, even if Romani people cannot.

The usual omission of Romani narratives in Holocaust representations is what makes the Wiener Holocaust Library’s recent exhibit, Forgotten Victims: The Nazi Genocide of the Roma and Sinti, so significant. Despite many Romani narratives being treated as separate to the Jewish genocide—or as a (literal) footnote—the Wiener makes them the focal point of their exhibit. The exhibit combines eye-witness accounts, photographs, documents and books to tell the story of the Roma and Sinti Holocaust. Other Wiener exhibition documents personalise the devastation of genocide by including the pictures and names of those who survived and those who perished.

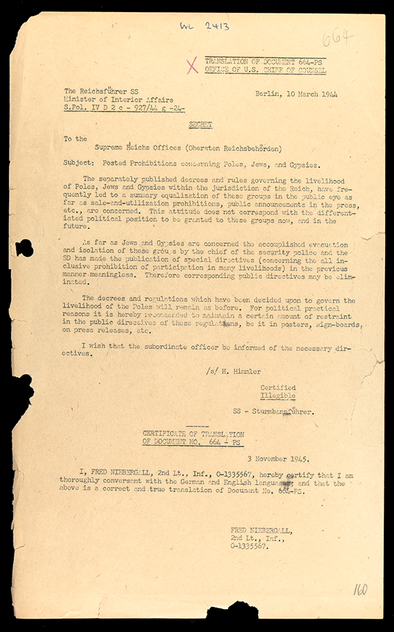

While the Roma and Sinti Holocaust is often, controversially, treated as a separate genocide to the mass slaughtering of Jewish people, based on the Württemburg Ministry for the Interior claiming in 1951 that Roma and Sinti were persecuted for being “asocial” or “criminals” rather than for their race, the Wiener Library displays documents that push back against that assertion. One letter, labelled document 664-PS, dated 10 March 1944 and signed by leading member of the Nazi Party Heinrich Himmler, expresses the goal of genocide against Romani and Jewish people in brutally bureaucratic language, stating “the accomplished evacuation and isolation” of Jews and Gypsies meant that directives against these groups were no longer necessary.

Another item, a 1945 testimony from Jewish survivor Hermann Langbein, describes the “Gypsy Family Camp” in Auschwitz in graphic detail:

[su_quote]... the conditions were worse than in other camps … in April 1943 I was outside, and I saw the following. The route between the huts was ankle deep in mud and dirt. The gypsies were still wearing the clothes that they had been given upon arrival … footwear was missing … The latrines were built in such a way that they were practically unusable for the gypsy children. The infirmary was a pathetic sight.[/su_quote]Forgotten victims and silences in the archive

For Romani representation more broadly, the European archive is a cruel place. Racial oppression, and genocide rhetoric and tactics, did not start with the Holocaust. Nor did they end there. Regarding the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, scholar Saidiya Hartman states that “the archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property … a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.” While these two historic narratives of violent oppression have differences that should not be forgotten, there are stark similarities in how the archive also erases evidence of the realities of Romani people, reducing them to malleable figures for the fears and fantasies of white Europeans.

The Wiener Holocaust Library’s own extensive archive is an exception to this rule. The archive was founded by Dr Alfred Wiener, a German Jewish man who, with his family, fled rising-antisemitism in Germany in 1933. While visiting the library on a trip to London, I had a chance to interview the exhibit’s curator Barbara Warnock, who explained, “[Wiener] specifically wanted to document, record, and research antisemitism in Germany and across Europe … in the course of this work, our organization was interested in and concerned about persecution against Roma and gathered those materials.”

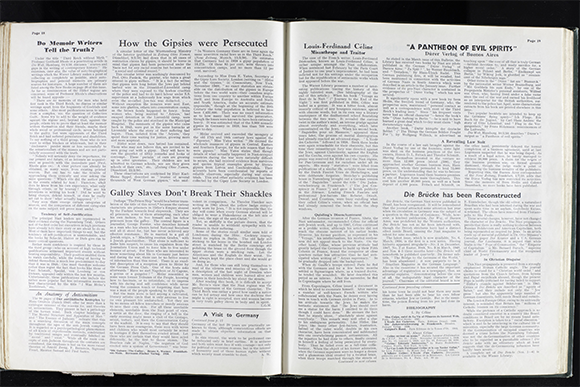

One of the documents on display in the exhibit is a 1950 article titled “How the Gipsies were Persecuted,” written by the editor of The Wiener Library Bulletin, C.C. Aronsfeld. The essay responds to German arguments that Romani people were not persecuted due to racist ideologies, but were instead imprisoned because they were “criminal”—an argument which reflects lasting stereotypes about Roma and Sinti. Aronsfeld quotes the Gipsy Lore Society’s Dora Yates to refute this sentiment, insisting that the persecution of Romani people during the Holocaust was based on their ethnicity. In the 1960s, the Library would go on to fund a large research project to collect documentation on Roma and Sinti genocide during the Holocaust, recording testimonies from Roma and Sinti survivors as well as Jewish survivors who witnessed Romani persecution.

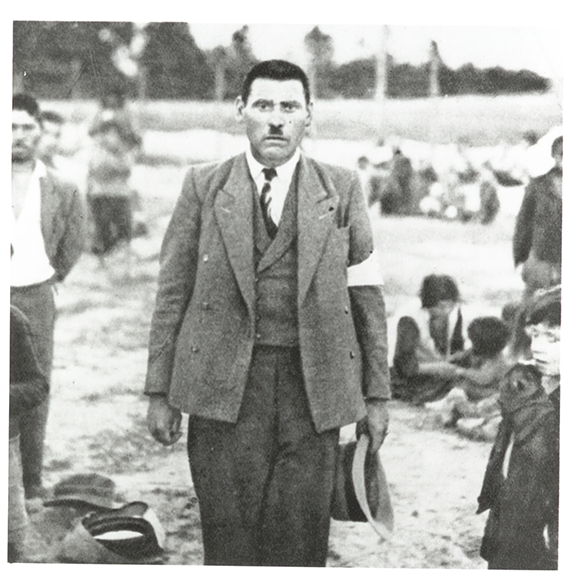

While the latest exhibition was put together by the Wiener Holocaust Library and shaped by their own substantial archives, they also worked with the Roma Support Group to obtain photographs of survivors and victims alike. These archival documents include a picture of Margarete Kraus, a Czech Roma woman, photographed after the Second World War. According to a report made by journalist Reimer Gilsenbach in 1966, Kraus was deported to Auschwitz with her parents in 1943. Both of her parents died in the concentration camp while she was subjected to forced medical experimentations, ultimately surviving the torture and genocide.

Other items detail sexual violence against Romani women. In testimony from 1958, Hermine Horvath, an Austrian Roma woman, explicitly details sexual abuse at the hands of SS officers, including the rape and murder of two Roma children in Auschwitz. Although Horvath survived the concentration camps, she passed away at the age of 33—perhaps succumbing to the violence she faced as a camp inmate, slave labourer, and victim of medical experimentation.

The politics of memory

While the designation of “Forgotten Holocaust,” first coined by historian Professor Eve Rosenhaft, was meant to draw attention to the lack of representation for Roma and Sinti Holocaust persecution, the word “forgotten” begs the question: forgotten by who? Romani survivors and activists have long been shouting to be heard against deafening silence. I don’t think they ever stopped.

The problem with the term “Forgotten Holocaust,” then, is that it relieves those who forgot of their failure, ignoring the fact Roma and Sinti survivors and activists have long implored politicians, historians, and large organizations to remember.

What gives all this particular poignancy in this populist moment is that, across much of Europe, anti-Romani racism remains prevalent. Media misrepresentation is accompanied by discriminatory statements and legislation from politicians, including in the recent UK general election, when the Conservative Party manifesto outlined a pledge to introduce new powers to seize “the property and vehicles of trespassers who set up unauthorised encampments”—a proposal aimed squarely at Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities.

This is just one example of the insidious way contemporary anti-Romani racism is embedded in public policy in different parts of the world. Sometimes it is education segregation, sometimes police and government racial registrations, elsewhere anti-immigration laws and practices, forced sterilisations, sexual assault and trafficking, and imbalanced incarceration rates. All this reflects and fuels the prejudice that underlies the rise of racially-motivated murders of Romani people across Europe.

What’s more, while some countries have acknowledged their participation in the Roma and Sinti Holocaust—like Germany’s 1982 admission of race-based genocide against Romani people and France’s apology in 2016 for collaborating with Nazis to persecute Romani people—many conservative political regimes still maintain their silence regarding Romani oppression. In the Czech Republic, MP Jaroslav Foldyna, the vice-chair of the Czech Social Democratic Party (SSD), publicly insulted Roma and Sinti Holocaust victims as recently as this January.

The danger of forgetting is that this large-scale genocide of Romani people could plausibly happen again. In an interview with Time magazine, Daniela Abraham, founder of the Sinti Roma Holocaust Memorial Trust and the granddaughter of a Roma Holocaust survivor, said: “I don’t want our people who have suffered at the hands of the Nazis to be forgotten. They deserve to be remembered.” She added: “If you don’t educate the public about the Roma Holocaust, then future generations could do the same thing.”

With the recent popularity of European ethnonationalist regimes and rising anti-Romani attacks, there is a particular urgency in remembering the devastation and destruction of the Holocaust. As Roma Holocaust survivor Ceija Stojka has famously remarked, “I’m afraid that Europe is forgetting its past and that Auschwitz is only sleeping.”

A fight towards remembering

Romani people have a history of resistance and resilience, so much so that it is memorialized in our own international day of remembrance: Romani Resistance Day. This day memorializes the Roma and Sinti uprising in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on May 16th, 1944.

The Wiener Holocaust Library’s exhibit also contains archival documents speaking to resistance from Holocaust victims. Vinzenz Rose (1908-1996) was a Sinti man who was forced out of his cinema business due to racial persecution in 1937, subsequently living under false identities in Germany and Czechoslovakia from 1940 until 1943, when he was arrested by the Gestapo. He was deported to Auschwitz, forced into slave labour and subjected to medical experimentation. In April 1944, Rose was transferred to Neckarelz, a satellite camp of the Natzweiler concentration camp, from where he escaped. With his brother Oskar, Rose hired a private detective to track down Nazi scientist, Robert Ritter. This pursuit was, alas, unsuccessful.

This legacy of resistance has become the pulse of Romani activism and helped fuel a global fight for equal rights and representation. Romani scholars and activists have also formed their own archive, RomArchive, privileging Romani narratives and cultural materials often ignored elsewhere. Recently, Roma activists and scholars have also been impacting major institutions. In 2016, Romani scholar and activist Ethel Brooks was appointed by President Obama to the governing body of the Washington-based U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Abraham was one of the keynote speakers at the Wiener Holocaust Library exhibit, along with Rabbi Jonathon Wittenberg. In his moving speech, Wittenberg tapped into the shared oppressions between Romani and Jewish people, calling for solidarity between the two minoritized groups when he stated, “We share together the responsibility of learning about this legacy. It affects those who were then and those who are now.”

This solidarity, along with institutions like the Wiener Holocaust Library shedding light on these histories, are stepping-stones towards a future in which Romani can thrive. Despite the constant reminders of racial violence, within the fight for liberation is a deep, impactful cultural love. What do resistance and resilience look like if not the preservation of our culture, our history, and our people?

In Europe is Ours: A Manifesto, Brooks paints a better future for Romani people, positing,

[su_quote]We claim nationhood without aspiring to the hierarchy of the nation-state; nor do we aspire to the tyranny of the border or the imperative to empire that are part of the legacy of Europe, embodied in the current system of nation-states .... We demand the freedom to cross borders and the ability to settle without fear of expulsion and deportation. We claim security from racist violence, demand safety from ultranationalist killings … we claim recognition of and reparations for those killed by the Nazis and their allies. We claim freedom. [/su_quote]Even if the narrative of the “forgotten Holocaust” is perpetuated time and time again, Romani people have not forgotten. We are an extant people. We will always remember. We will always keep fighting for remembrance. It’s in our bones.