Read more: Can he get anything done?Listen: Ockrent talks to Prospect Editor Tom Clark in the ninth edition of Headspace, our monthly podcast

Emmanuel Macron is the new president of France. After five disappointing years, François Hollande has left the Elysée Palace. And Le cher et vieux pays, the “dear old country” celebrated by Charles de Gaulle—who was 68 when he founded the Fifth Republic in 1958—has fallen into the arms of a 39-year-old political novice with no party machine.

The achievement of this young man is historic. At a time when the democratic process is under scrutiny on both sides of the Atlantic, Macron has broken the entire mould of French politics. Selecting him after a long, unpredictable and bitter presidential campaign, 66.1 per cent of French voters have sent a signal of hope, optimism and openness to the world. How could it happen in a nation with a reputation for being the most pessimistic in Europe? And how could a land at once so proud of its revolutionary tradition, and at the same time so solidly conservative in its political habits, have embraced an avowed centrist who proudly stands outside the old tribes of left and right?

Macron was at first considered a fraud, a hologram, a self-deluded caricature. He was seen as a spoiled brat, not in the class-conscious Eton-Oxford English sense, but in a French way that combines high education and a technocratic mindset with intellectual pretention. His blue-eyed good looks didn’t help. Before long he was also labelled a traitor to his boss, Hollande, to Manuel Valls, the head of the government in which he served, and to the Socialist Party he pretended to support. Back then, he was seen as a bubble, which the changing winds of the popular mood would soon blow away, a passing infatuation for the media which was bored of the drear of politics as usual. He was painted as a caricature of the globalised elite, a former banker, the gilded champion of the oligarchy. Above all, he was a weather vane who bent with the winds and denied the basic political divide between the right and the left, a failing candidate who would never master the rules of the game.

Thirteen months ago, he launched En Marche! a political movement bearing his own initials and staffed by a handful of young, devoted aides. Less than a year before that, he resigned from the government and from the civil service, and now he has reached the one and only goal he had longed for: the Elysée.

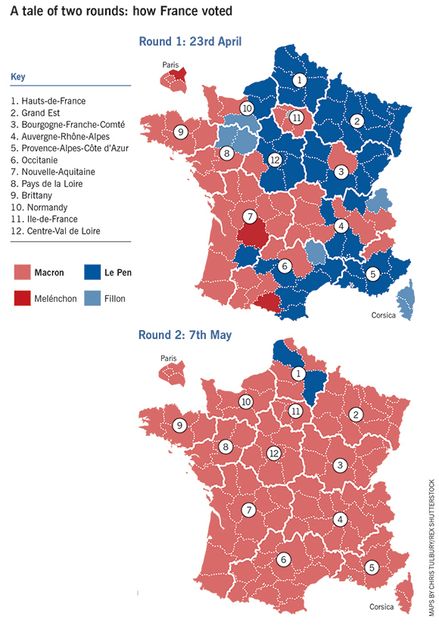

The elections that have brought him there have remade the entire terrain of French politics. In the first round of the election, on 23rd April, the French got rid of both the two parties that had dominated French politics and government for the past 60 years. Since then, François Fillon’s conservative Les Républicains (LRs)—the current incarnation of the Gaullists—and Benoît Hamon’s Parti Socialiste (PS) have been blaming one another, settling internal scores while pretending to be unified, and arguing that the internal primaries used to pick their candidates should never have been held, as if a bit of fixing in the back-office of the party machine could have saved them from the rage of the voters. Ahead after the first round, both Macron and Marine Le Pen, the Front National (FN) candidate, ran against the establishment as if they didn’t belong to it. In fact, he is one of its finest specimens, and she is the family heir to a far-right movement which has now been around for 44 years.

In the fierce duel that followed, they fought to attract voters of all persuasions. Part of the far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s support swung to the far right, as did the staunchly Catholic chunk of the conservative bloc. But most supporters of the mainstream right and left rallied to Macron. Hollande, in his last words as president, called for national unity against the far right, as did Fillon and his defeated rivals for the LR nomination, former president Nicolas Sarkozy and former prime minister Alain Juppé. So the vaunted “Republican front” against the far right held up to a point. Macron’s victory, however, ranks far behind the 82.2 per cent of the second round ballot with which Jacques Chirac was able to crush Marine’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, in 2002. Fifteen years on, the old arguments that used to prevail automatically against the FN—its questioning of the Holocaust, its indulgence towards memories of Marshal Pétain’s Vichy regime, its nostalgia for a French Algeria that had ended in such bloody ruin—have lost their bite. To the younger generation, this is all ancient history they don’t necessarily care about.

Le Pen’s 11m votes are a tribute to her personal skill. Attuned to the anger and fear of the dispossessed, the nativists, the losers of globalisation, she has deployed a rhetoric similar to that of Donald Trump, and made a political platform beset by obvious shortcomings and contradictions seem palatable to many disillusioned citizens.

Identity, nationalism, protection against immigration, rejection of Europe: Le Pen’s stark programme reflects the “declensionist” arguments of contemporary populism. More than three French voters in 10 were convinced by the angry pessimism she holds up as a vision, and picked her to run the country—a remarkable outcome, and one which demonstrates that parricide can pay. Two years ago she expelled her father from the party he founded in 1972 and proceeded to “de-demonise” it. Changing the narrative, cleansing the movement of its anti-Semitism, stirring up anti-Muslim fear instead, pouncing on assorted other traditional obsessions of the far right, she made some clever tactical moves, such as when she confronted Macron in his home town of Amiens on an industrial site where the work was about to be outsourced to Poland. But the FN’s revisionist approach to the past eventually caught up with her. The savvy political operator slipped back into the traditional sewers of the far right. Her claim that France was not responsible for the infamous “Vel d’Hiv” round-up of Jews in Paris in 1942, for deportation to Nazi concentration camps, reminded voters of her father’s many objectionable statements. (He once referred to the Holocaust as “a detail” of history.) It didn’t prevent the Catholic movement Sens Commun from joining forces with her, nor did it dissuade Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, the leader of a fringe party on the Eurosceptic right, from trading his 4.7 per cent of the first-round presidential vote against the promise that he would become her prime minister, and his campaign costs would be paid.

Le Pen’s performance at the television debate four days before the election damaged much of the laundering she had conducted on her own image. Aggressive, verbally violent, resorting to Trumpian-style “alternative facts” over most issues. She was suddenly reminiscent of the traditional far-right of the 1930s and muddled the details of her own economic programme. Macron stuck to rational explanations, shrewdly contrasting her lack of coherent proposals with his own presidential demeanour. Polls taken after the televised head-to-head showed that two-thirds of viewers judged he had won the contest. But although she lost the presidential fight, Le Pen has built an almighty illiberal force, and succeeded, too, in planting her favourite themes at the heart of the national debate. Despite the 25 per cent abstention rate and 11 per cent of ballots spoiled, the legacy of this strong FN showing will be felt for a long time to come.

Nevertheless, Macron’s achievement is unprecedented. He has done what pundits thought impossible. He outdid both mainstream parties, by exploiting their internal divisions on myriad issues, from the economy to labour regulations and Europe. The early support from François Bayrou, the long-time centrist leader, was a help. Throughout the campaign, he talked about progress, openness and confidence in the country’s assets. He spoke about patriotism rather than nationalism, and held up the European Union as the best way to maintain French influence and prosperity. His optimism, his liberal convictions, tempered by a social conscience, partly overcame all the criticisms—about the haziness of his programme, and his uncanny ability to be on all sides of every argument.

Falling at times into abstruse technocratic language, Macron tried and sometimes failed to sweep away every emotive charge made by his opponents with dry facts and cold reason. He made mistakes. Celebrating his first round results in a brasserie in Montparnasse was the wrong signal to send to critics eager to compare him to Sarkozy’s self-serving flamboyance. Yet his calm authority, his determination not to make false promises, became a trademark. His response to the massive cyber-attack that hit his campaign shortly before election day was firm and restrained. His acceptance speech on 7th May was solemn and politically well tuned, addressing first the “other France,” meaning all those who did not want to see him elected, and asking for everybody’s support to help build a new era of optimism and recovery. Statesmanship is a learning process.

Napoleon used to say he would select his generals not for their strategic skill or personal bravery, but for one crucial attribute: luck. Luck certainly makes up a good part of talent in politics, and Macron has proved to be remarkably lucky. The political story of these past few months is one no one would have written in advance. Last November Juppé was so convinced he was going to win the conservative primary that he started sketching out his government team. He lost to Fillon who then enjoyed the sort of ratings which, when combined with the abysmal numbers of Hollande’s socialists, meant that there was no way he could possibly lose. Then, in December, to the surprise of all sides, Hollande announced that he would not run for a second term as president, something that had never happened in the course of the Fifth Republic. Valls, his prime minister, resigned in order to run for the nomination, but then in January there came another swerve in the political plot, when Valls lost heavily to Hamon, one of his former ministers, a frondeur—or rebel—hostile to Valls’s centrist brand of social democracy. The triumphant Hamon started campaigning against his own comrades’ performance over the previous five years, and duly started sinking.

Then Fillon got entangled in a series of scandals. The press discovered that his wife, Penelope, a Welsh woman from Abergavenny, and two of his children had been paid with public money to work for him in parliament, but had allegedly barely lifted a finger for these wages. A judicial investigation was launched. The candidate’s taste for bespoke suits became another issue when a lobbyist involved in dubious French-African deals gave details of expensive gifts. In Fillon’s defence, such lax personal ethics are far from unusual among French politicians—the home secretary had to resign for employing his teenage daughters when he was an MP. But the conservative candidate had played “Mr Clean,” and exploited Sarkozy’s legal problems to push him aside. He had also promised he would drop out if formally charged, which he then failed to do.

The Republicans became paralysed. A wounded Juppé refused to take over. Denouncing an Elysée conspiracy to kill him politically, Fillon turned more and more to the right. The traditionalist Sens Commun, which had fought against gay marriage and opposes legal abortion, became his stronghold. On 23rd April, Fillon could muster only 20 per cent of the vote, which was not enough. For the first time in 70 years, mainstream conservatives had no runner in the race for the Elysée.

As for the Socialists, Hamon ended up with a humiliating 6.3 per cent of the ballot, crushed by the far left candidate, Mélenchon. Through powerful public speaking, social media skills and the support of the remnants of the Communist Party, the former Socialist senator convinced 19.5 per cent of French voters, particularly the young, that his strange blend of Castro, Chavez and anti-European populism was the answer to the country’s problems. As earthquake followed earthquake, France’s political geography was entirely reshaped, and in a manner which provided a clear road to the Elysée for Macron.

The new president is the youngest ever—Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, the previous youngest, was nearly a decade older when he was elected in 1974 at the age of 48. The wonder boy had never before run for parliament or any elected office. His experience of public affairs has been limited to two years as a presidential adviser, and another two years as economy minister in the Valls government, and the way he got even this limited experience of French public life was decidedly unusual.

Before politics, Macron was an investment banker with the Rothschild firm and made very good money—usually a mortal sin in a country where other people’s wealth arouses suspicion. A civil servant trained at the ENA elite school, he had been spotted by Jacques Attali, who put him on a high-powered group asked by Sarkozy in 2008 to draft new priorities for the country. Their conclusions were useful and provocative and though none of them became government policy, the brilliant young Macron forged useful connections for the future.

In 2012, Hollande was elected president. Jean-Pierre Jouyet, Macron’s life-time friend, became chief of staff of the Elysée two years later and worked closely with Macron who was serving as deputy secretary-general—Macron was 34, and perfectly positioned to watch Hollande fall into one political trap after another. He saw up close how wrong it had been for the president to promise he would be “normal” when the French long for monarchical style—“the president needs to be like Jupiter!” his young adviser would say later. He witnessed his boss’s inability to take decisions, listening to everybody without imposing his point of view. He saw the damage inflicted by Hollande’s appetite for talking to journalists and by the gap between his good-natured manner and his insensitive approach to some of his closest aides’ personal problems. Macron fell out of love.

When Valls ousted some government members overtly opposed to his liberalising policies, Macron was given the economic portfolio. But their relationship became tense as Macron became eager to show his independence and build his own reputation. As a member of an unpopular government, it is probably just as well for him that he was an unknown quantity to most of his countrymen. More liberal than his prime minister and eager to promote entrepreneurship and labour market deregulation, he cultivated his start-up style and developed his own links in the business community. He also worked hard at becoming more visible. As the story goes, taking part in his official capacity in the annual celebration of the life of Joan of Arc, Macron went to Orléans—the city where Joan “la Pucelle” famously exhorted soldiers to kick the English out. There he decided that it was his mission to lead the French back to glory. Indeed, at his first public meeting in Paris last December, the candidate sounded like an exalted preacher yelling to the heavens as 10,000 people were chanting his name.

Emmanuel—a name that means “God is with us” in ancient Hebrew—had been preparing for a long time. Born in Amiens, a small provincial city north of Paris, to a typical middle class family—both his parents are doctors—the boy was an exceptional student. His maternal grandmother, Manette, was the dominant influence, a former teacher of humble origins and an avid amateur student of French literature. Racine and Stendhal, Chateaubriand and Camus, René Char, Pascal Quignard… young Macron, who was for a while philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s assistant, would never abandon the realm of words. Manette and her grandson developed an unusual bond and, sticking to the French tradition that public figures must publish a book to be taken seriously, Macron wrote about her in his manifesto Revolution. When his grandmother died in 2013, he was devastated. “Please help him! Show him your love and affection!” cried his wife Brigitte, asking their friends for support.

Brigitte is the pillar of Emmanuel’s life. Twenty-four years his senior, she was his theatre coach at school when he was in his teens. Born to a family that had grown prosperous making chocolate over five generations, married to a banker and mother of three children—her daughter was Macron’s classmate—she taught French in the best Catholic school in Amiens. In the true Balzacian tradition, her love affair with the young man would become a local scandal. They both remained constant, slowly gaining their families’ support. At 16, leaving for Paris to study in a more competitive environment, Emmanuel promised to come back and marry her. He did. Thirteen years later, the ceremony took place in Le Touquet, a seaside resort on the Channel, where she owns a house. He thanked all those who had allowed for their happy ending, starting with his own mother and his wife’s children. Her grandchildren call him Daddy.

“Brigitte et Emmanuel, Emmanuel et Brigitte”… On official occasions or on holidays, kissing, holding hands, with her adoring smile and slender silhouette elegantly clad by the best designers, Brigitte has been from the start a key feature in Macron’s political pitch. Celebrity magazines devoted dozens of covers to “the incredible couple.” Her natural warmth and easy approach did wonders, and though in other countries and other circumstances the age gap and their unusual courtship might have caused problems, the French electorate merely shrugged. During the presidential campaign, behind the scenes or on stage, with supporters chanting her name, she was an asset. He has promised to give her official status—even the American president’s wife does not have one, nor the British PM’s husband. Nobody knows yet what it might entail.

Has Brigitte’s unconditional love and support reinforced Macron’s self-confidence? Or is it simply a by-product of his intellectual agility and capacity to charm? After all, these are the usual ingredients of political charisma. The new French president is reminiscent of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton in their heydays, though perhaps Macron is a little smoother, and more aloof.

Indeed, in these days of Brexit and Trump, championing open modernity in the altogether more challenging climate of the austerity years, Macron may strike some Anglo-Saxon readers as a creature out of his time, the kind of figure one might have expected to thrive only before the banking crisis of 2008.

But his policy platform is a shrewd mix of economic liberalism and social protection, of conservative discipline and social democrat concern for welfare; a prescription for domestic reforms to cut deficits, stimulate growth, attract more investment and tame globalisation. This is combined with a drive to enhance the country’s status in Europe and improve counter-terror measures.

Although in much of the west a lot of this is taken for granted, in France his positioning is audacious. It is well over half a century since the German Social Democrats reconciled itself to capitalism at its Bad Godesberg convention of 1959, but the mainstream of the French left has never made the same journey. The market system is still up for debate, and even on the right, one can hear moderates who consider it an “Anglo-Saxon” plot to drown French identity. Liberalism does not come easy in France—its very definition is blurred, and “ultraliberal” has become a customary insult. Breaking with the past, the president intends, in his own words, to lead “the progressives” or reformists against the “conservatives.” Blair railed against the “forces of conservatism” on the left and the right in much the same way, but he did so in post-Thatcher Britain. Macron faces a much more formidable task in convincing France, where the old ideological cleavages cut very deep, that it is no longer the left/right split, but instead the moderniser/nostalgic distinction that is the real divide in the country.

Macron, then, has already transformed the terms of France’s party political trade. As president he will retain a uniquely powerful voice in setting the agenda. But a daunting task lies ahead. To get his full programme through in a difficult economic and social environment, he will have to marshal majorities in what will probably be a fractured parliament. Legislative elections are due in June. En Marche! will field candidates all over the country. Macron promised to dilute the political elites, and so his candidates will include new faces from outside politics who will go up against traditional party machines. According to the polls, they could fare well, but even after Macron’s remarkable march on the Elysée, his untrained army of hopefuls, who lack an established machine, stand little chance of securing an overall majority. After grudgingly supporting Macron to stop Le Pen, conservative MPs will fight hard to become the main opposition force. The Socialists will probably be crushed and the far left, to Mélenchon’s disappointment, may find it hard to make a breakthrough. The far right will win seats but not enough to lead the opposition.

During the Presidential campaign, Macron played down the issue of building a governing majority, maintaining that he would garner support project by project. Valls has now expressed an interest in joining En Marche!. On the conservative side, the generational and ideological split between the various factions will give the Elysée some room for manoeuver. Across the board, French politicians might learn to compromise, a process quite foreign to both the traditions and the institutions of the Fifth Republic.

The new government, which includes conservatives as well as social democrats, illustrates the new president’s bipartisan or rather post-partisan intentions. Whereas in 2002 Chirac eventually shared his broad victory over Jean-Marie Le Pen exclusively with his own party, Macron has not made the same mistake.

Macron’s election is a welcome signal of hope in post-Brexit Europe. But there should be no misunderstanding. He has been chosen by only half of the country: the better-educated, urbanised, globalised, more affluent part of French society. The huge challenge is how to convince the other half that he can move them forward: the angry and the dispossessed losers from globalisation, the disenchanted young generation, which faces unemployment rates of 25 per cent.

Work has to begin immediately. Strong signals have to be sent to start reforming labour laws and the tax system while investing in education and security. There will be no strikes during the summer. The French usually care for their holidays. In September, the return to work—the rentrée—will be rocky. But then, as Macron likes to say, “Life is invention.” His own is proof of that.

Emmanuel Macron is the new president of France. After five disappointing years, François Hollande has left the Elysée Palace. And Le cher et vieux pays, the “dear old country” celebrated by Charles de Gaulle—who was 68 when he founded the Fifth Republic in 1958—has fallen into the arms of a 39-year-old political novice with no party machine.

The achievement of this young man is historic. At a time when the democratic process is under scrutiny on both sides of the Atlantic, Macron has broken the entire mould of French politics. Selecting him after a long, unpredictable and bitter presidential campaign, 66.1 per cent of French voters have sent a signal of hope, optimism and openness to the world. How could it happen in a nation with a reputation for being the most pessimistic in Europe? And how could a land at once so proud of its revolutionary tradition, and at the same time so solidly conservative in its political habits, have embraced an avowed centrist who proudly stands outside the old tribes of left and right?

Macron was at first considered a fraud, a hologram, a self-deluded caricature. He was seen as a spoiled brat, not in the class-conscious Eton-Oxford English sense, but in a French way that combines high education and a technocratic mindset with intellectual pretention. His blue-eyed good looks didn’t help. Before long he was also labelled a traitor to his boss, Hollande, to Manuel Valls, the head of the government in which he served, and to the Socialist Party he pretended to support. Back then, he was seen as a bubble, which the changing winds of the popular mood would soon blow away, a passing infatuation for the media which was bored of the drear of politics as usual. He was painted as a caricature of the globalised elite, a former banker, the gilded champion of the oligarchy. Above all, he was a weather vane who bent with the winds and denied the basic political divide between the right and the left, a failing candidate who would never master the rules of the game.

Thirteen months ago, he launched En Marche! a political movement bearing his own initials and staffed by a handful of young, devoted aides. Less than a year before that, he resigned from the government and from the civil service, and now he has reached the one and only goal he had longed for: the Elysée.

The elections that have brought him there have remade the entire terrain of French politics. In the first round of the election, on 23rd April, the French got rid of both the two parties that had dominated French politics and government for the past 60 years. Since then, François Fillon’s conservative Les Républicains (LRs)—the current incarnation of the Gaullists—and Benoît Hamon’s Parti Socialiste (PS) have been blaming one another, settling internal scores while pretending to be unified, and arguing that the internal primaries used to pick their candidates should never have been held, as if a bit of fixing in the back-office of the party machine could have saved them from the rage of the voters. Ahead after the first round, both Macron and Marine Le Pen, the Front National (FN) candidate, ran against the establishment as if they didn’t belong to it. In fact, he is one of its finest specimens, and she is the family heir to a far-right movement which has now been around for 44 years.

In the fierce duel that followed, they fought to attract voters of all persuasions. Part of the far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s support swung to the far right, as did the staunchly Catholic chunk of the conservative bloc. But most supporters of the mainstream right and left rallied to Macron. Hollande, in his last words as president, called for national unity against the far right, as did Fillon and his defeated rivals for the LR nomination, former president Nicolas Sarkozy and former prime minister Alain Juppé. So the vaunted “Republican front” against the far right held up to a point. Macron’s victory, however, ranks far behind the 82.2 per cent of the second round ballot with which Jacques Chirac was able to crush Marine’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, in 2002. Fifteen years on, the old arguments that used to prevail automatically against the FN—its questioning of the Holocaust, its indulgence towards memories of Marshal Pétain’s Vichy regime, its nostalgia for a French Algeria that had ended in such bloody ruin—have lost their bite. To the younger generation, this is all ancient history they don’t necessarily care about.

Le Pen’s 11m votes are a tribute to her personal skill. Attuned to the anger and fear of the dispossessed, the nativists, the losers of globalisation, she has deployed a rhetoric similar to that of Donald Trump, and made a political platform beset by obvious shortcomings and contradictions seem palatable to many disillusioned citizens.

Identity, nationalism, protection against immigration, rejection of Europe: Le Pen’s stark programme reflects the “declensionist” arguments of contemporary populism. More than three French voters in 10 were convinced by the angry pessimism she holds up as a vision, and picked her to run the country—a remarkable outcome, and one which demonstrates that parricide can pay. Two years ago she expelled her father from the party he founded in 1972 and proceeded to “de-demonise” it. Changing the narrative, cleansing the movement of its anti-Semitism, stirring up anti-Muslim fear instead, pouncing on assorted other traditional obsessions of the far right, she made some clever tactical moves, such as when she confronted Macron in his home town of Amiens on an industrial site where the work was about to be outsourced to Poland. But the FN’s revisionist approach to the past eventually caught up with her. The savvy political operator slipped back into the traditional sewers of the far right. Her claim that France was not responsible for the infamous “Vel d’Hiv” round-up of Jews in Paris in 1942, for deportation to Nazi concentration camps, reminded voters of her father’s many objectionable statements. (He once referred to the Holocaust as “a detail” of history.) It didn’t prevent the Catholic movement Sens Commun from joining forces with her, nor did it dissuade Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, the leader of a fringe party on the Eurosceptic right, from trading his 4.7 per cent of the first-round presidential vote against the promise that he would become her prime minister, and his campaign costs would be paid.

Le Pen’s performance at the television debate four days before the election damaged much of the laundering she had conducted on her own image. Aggressive, verbally violent, resorting to Trumpian-style “alternative facts” over most issues. She was suddenly reminiscent of the traditional far-right of the 1930s and muddled the details of her own economic programme. Macron stuck to rational explanations, shrewdly contrasting her lack of coherent proposals with his own presidential demeanour. Polls taken after the televised head-to-head showed that two-thirds of viewers judged he had won the contest. But although she lost the presidential fight, Le Pen has built an almighty illiberal force, and succeeded, too, in planting her favourite themes at the heart of the national debate. Despite the 25 per cent abstention rate and 11 per cent of ballots spoiled, the legacy of this strong FN showing will be felt for a long time to come.

Nevertheless, Macron’s achievement is unprecedented. He has done what pundits thought impossible. He outdid both mainstream parties, by exploiting their internal divisions on myriad issues, from the economy to labour regulations and Europe. The early support from François Bayrou, the long-time centrist leader, was a help. Throughout the campaign, he talked about progress, openness and confidence in the country’s assets. He spoke about patriotism rather than nationalism, and held up the European Union as the best way to maintain French influence and prosperity. His optimism, his liberal convictions, tempered by a social conscience, partly overcame all the criticisms—about the haziness of his programme, and his uncanny ability to be on all sides of every argument.

Falling at times into abstruse technocratic language, Macron tried and sometimes failed to sweep away every emotive charge made by his opponents with dry facts and cold reason. He made mistakes. Celebrating his first round results in a brasserie in Montparnasse was the wrong signal to send to critics eager to compare him to Sarkozy’s self-serving flamboyance. Yet his calm authority, his determination not to make false promises, became a trademark. His response to the massive cyber-attack that hit his campaign shortly before election day was firm and restrained. His acceptance speech on 7th May was solemn and politically well tuned, addressing first the “other France,” meaning all those who did not want to see him elected, and asking for everybody’s support to help build a new era of optimism and recovery. Statesmanship is a learning process.

Napoleon used to say he would select his generals not for their strategic skill or personal bravery, but for one crucial attribute: luck. Luck certainly makes up a good part of talent in politics, and Macron has proved to be remarkably lucky. The political story of these past few months is one no one would have written in advance. Last November Juppé was so convinced he was going to win the conservative primary that he started sketching out his government team. He lost to Fillon who then enjoyed the sort of ratings which, when combined with the abysmal numbers of Hollande’s socialists, meant that there was no way he could possibly lose. Then, in December, to the surprise of all sides, Hollande announced that he would not run for a second term as president, something that had never happened in the course of the Fifth Republic. Valls, his prime minister, resigned in order to run for the nomination, but then in January there came another swerve in the political plot, when Valls lost heavily to Hamon, one of his former ministers, a frondeur—or rebel—hostile to Valls’s centrist brand of social democracy. The triumphant Hamon started campaigning against his own comrades’ performance over the previous five years, and duly started sinking.

Then Fillon got entangled in a series of scandals. The press discovered that his wife, Penelope, a Welsh woman from Abergavenny, and two of his children had been paid with public money to work for him in parliament, but had allegedly barely lifted a finger for these wages. A judicial investigation was launched. The candidate’s taste for bespoke suits became another issue when a lobbyist involved in dubious French-African deals gave details of expensive gifts. In Fillon’s defence, such lax personal ethics are far from unusual among French politicians—the home secretary had to resign for employing his teenage daughters when he was an MP. But the conservative candidate had played “Mr Clean,” and exploited Sarkozy’s legal problems to push him aside. He had also promised he would drop out if formally charged, which he then failed to do.

The Republicans became paralysed. A wounded Juppé refused to take over. Denouncing an Elysée conspiracy to kill him politically, Fillon turned more and more to the right. The traditionalist Sens Commun, which had fought against gay marriage and opposes legal abortion, became his stronghold. On 23rd April, Fillon could muster only 20 per cent of the vote, which was not enough. For the first time in 70 years, mainstream conservatives had no runner in the race for the Elysée.

As for the Socialists, Hamon ended up with a humiliating 6.3 per cent of the ballot, crushed by the far left candidate, Mélenchon. Through powerful public speaking, social media skills and the support of the remnants of the Communist Party, the former Socialist senator convinced 19.5 per cent of French voters, particularly the young, that his strange blend of Castro, Chavez and anti-European populism was the answer to the country’s problems. As earthquake followed earthquake, France’s political geography was entirely reshaped, and in a manner which provided a clear road to the Elysée for Macron.

The new president is the youngest ever—Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, the previous youngest, was nearly a decade older when he was elected in 1974 at the age of 48. The wonder boy had never before run for parliament or any elected office. His experience of public affairs has been limited to two years as a presidential adviser, and another two years as economy minister in the Valls government, and the way he got even this limited experience of French public life was decidedly unusual.

Before politics, Macron was an investment banker with the Rothschild firm and made very good money—usually a mortal sin in a country where other people’s wealth arouses suspicion. A civil servant trained at the ENA elite school, he had been spotted by Jacques Attali, who put him on a high-powered group asked by Sarkozy in 2008 to draft new priorities for the country. Their conclusions were useful and provocative and though none of them became government policy, the brilliant young Macron forged useful connections for the future.

In 2012, Hollande was elected president. Jean-Pierre Jouyet, Macron’s life-time friend, became chief of staff of the Elysée two years later and worked closely with Macron who was serving as deputy secretary-general—Macron was 34, and perfectly positioned to watch Hollande fall into one political trap after another. He saw up close how wrong it had been for the president to promise he would be “normal” when the French long for monarchical style—“the president needs to be like Jupiter!” his young adviser would say later. He witnessed his boss’s inability to take decisions, listening to everybody without imposing his point of view. He saw the damage inflicted by Hollande’s appetite for talking to journalists and by the gap between his good-natured manner and his insensitive approach to some of his closest aides’ personal problems. Macron fell out of love.

When Valls ousted some government members overtly opposed to his liberalising policies, Macron was given the economic portfolio. But their relationship became tense as Macron became eager to show his independence and build his own reputation. As a member of an unpopular government, it is probably just as well for him that he was an unknown quantity to most of his countrymen. More liberal than his prime minister and eager to promote entrepreneurship and labour market deregulation, he cultivated his start-up style and developed his own links in the business community. He also worked hard at becoming more visible. As the story goes, taking part in his official capacity in the annual celebration of the life of Joan of Arc, Macron went to Orléans—the city where Joan “la Pucelle” famously exhorted soldiers to kick the English out. There he decided that it was his mission to lead the French back to glory. Indeed, at his first public meeting in Paris last December, the candidate sounded like an exalted preacher yelling to the heavens as 10,000 people were chanting his name.

Emmanuel—a name that means “God is with us” in ancient Hebrew—had been preparing for a long time. Born in Amiens, a small provincial city north of Paris, to a typical middle class family—both his parents are doctors—the boy was an exceptional student. His maternal grandmother, Manette, was the dominant influence, a former teacher of humble origins and an avid amateur student of French literature. Racine and Stendhal, Chateaubriand and Camus, René Char, Pascal Quignard… young Macron, who was for a while philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s assistant, would never abandon the realm of words. Manette and her grandson developed an unusual bond and, sticking to the French tradition that public figures must publish a book to be taken seriously, Macron wrote about her in his manifesto Revolution. When his grandmother died in 2013, he was devastated. “Please help him! Show him your love and affection!” cried his wife Brigitte, asking their friends for support.

Brigitte is the pillar of Emmanuel’s life. Twenty-four years his senior, she was his theatre coach at school when he was in his teens. Born to a family that had grown prosperous making chocolate over five generations, married to a banker and mother of three children—her daughter was Macron’s classmate—she taught French in the best Catholic school in Amiens. In the true Balzacian tradition, her love affair with the young man would become a local scandal. They both remained constant, slowly gaining their families’ support. At 16, leaving for Paris to study in a more competitive environment, Emmanuel promised to come back and marry her. He did. Thirteen years later, the ceremony took place in Le Touquet, a seaside resort on the Channel, where she owns a house. He thanked all those who had allowed for their happy ending, starting with his own mother and his wife’s children. Her grandchildren call him Daddy.

“Brigitte et Emmanuel, Emmanuel et Brigitte”… On official occasions or on holidays, kissing, holding hands, with her adoring smile and slender silhouette elegantly clad by the best designers, Brigitte has been from the start a key feature in Macron’s political pitch. Celebrity magazines devoted dozens of covers to “the incredible couple.” Her natural warmth and easy approach did wonders, and though in other countries and other circumstances the age gap and their unusual courtship might have caused problems, the French electorate merely shrugged. During the presidential campaign, behind the scenes or on stage, with supporters chanting her name, she was an asset. He has promised to give her official status—even the American president’s wife does not have one, nor the British PM’s husband. Nobody knows yet what it might entail.

Has Brigitte’s unconditional love and support reinforced Macron’s self-confidence? Or is it simply a by-product of his intellectual agility and capacity to charm? After all, these are the usual ingredients of political charisma. The new French president is reminiscent of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton in their heydays, though perhaps Macron is a little smoother, and more aloof.

Indeed, in these days of Brexit and Trump, championing open modernity in the altogether more challenging climate of the austerity years, Macron may strike some Anglo-Saxon readers as a creature out of his time, the kind of figure one might have expected to thrive only before the banking crisis of 2008.

But his policy platform is a shrewd mix of economic liberalism and social protection, of conservative discipline and social democrat concern for welfare; a prescription for domestic reforms to cut deficits, stimulate growth, attract more investment and tame globalisation. This is combined with a drive to enhance the country’s status in Europe and improve counter-terror measures.

Although in much of the west a lot of this is taken for granted, in France his positioning is audacious. It is well over half a century since the German Social Democrats reconciled itself to capitalism at its Bad Godesberg convention of 1959, but the mainstream of the French left has never made the same journey. The market system is still up for debate, and even on the right, one can hear moderates who consider it an “Anglo-Saxon” plot to drown French identity. Liberalism does not come easy in France—its very definition is blurred, and “ultraliberal” has become a customary insult. Breaking with the past, the president intends, in his own words, to lead “the progressives” or reformists against the “conservatives.” Blair railed against the “forces of conservatism” on the left and the right in much the same way, but he did so in post-Thatcher Britain. Macron faces a much more formidable task in convincing France, where the old ideological cleavages cut very deep, that it is no longer the left/right split, but instead the moderniser/nostalgic distinction that is the real divide in the country.

Macron, then, has already transformed the terms of France’s party political trade. As president he will retain a uniquely powerful voice in setting the agenda. But a daunting task lies ahead. To get his full programme through in a difficult economic and social environment, he will have to marshal majorities in what will probably be a fractured parliament. Legislative elections are due in June. En Marche! will field candidates all over the country. Macron promised to dilute the political elites, and so his candidates will include new faces from outside politics who will go up against traditional party machines. According to the polls, they could fare well, but even after Macron’s remarkable march on the Elysée, his untrained army of hopefuls, who lack an established machine, stand little chance of securing an overall majority. After grudgingly supporting Macron to stop Le Pen, conservative MPs will fight hard to become the main opposition force. The Socialists will probably be crushed and the far left, to Mélenchon’s disappointment, may find it hard to make a breakthrough. The far right will win seats but not enough to lead the opposition.

During the Presidential campaign, Macron played down the issue of building a governing majority, maintaining that he would garner support project by project. Valls has now expressed an interest in joining En Marche!. On the conservative side, the generational and ideological split between the various factions will give the Elysée some room for manoeuver. Across the board, French politicians might learn to compromise, a process quite foreign to both the traditions and the institutions of the Fifth Republic.

The new government, which includes conservatives as well as social democrats, illustrates the new president’s bipartisan or rather post-partisan intentions. Whereas in 2002 Chirac eventually shared his broad victory over Jean-Marie Le Pen exclusively with his own party, Macron has not made the same mistake.

Macron’s election is a welcome signal of hope in post-Brexit Europe. But there should be no misunderstanding. He has been chosen by only half of the country: the better-educated, urbanised, globalised, more affluent part of French society. The huge challenge is how to convince the other half that he can move them forward: the angry and the dispossessed losers from globalisation, the disenchanted young generation, which faces unemployment rates of 25 per cent.

Work has to begin immediately. Strong signals have to be sent to start reforming labour laws and the tax system while investing in education and security. There will be no strikes during the summer. The French usually care for their holidays. In September, the return to work—the rentrée—will be rocky. But then, as Macron likes to say, “Life is invention.” His own is proof of that.