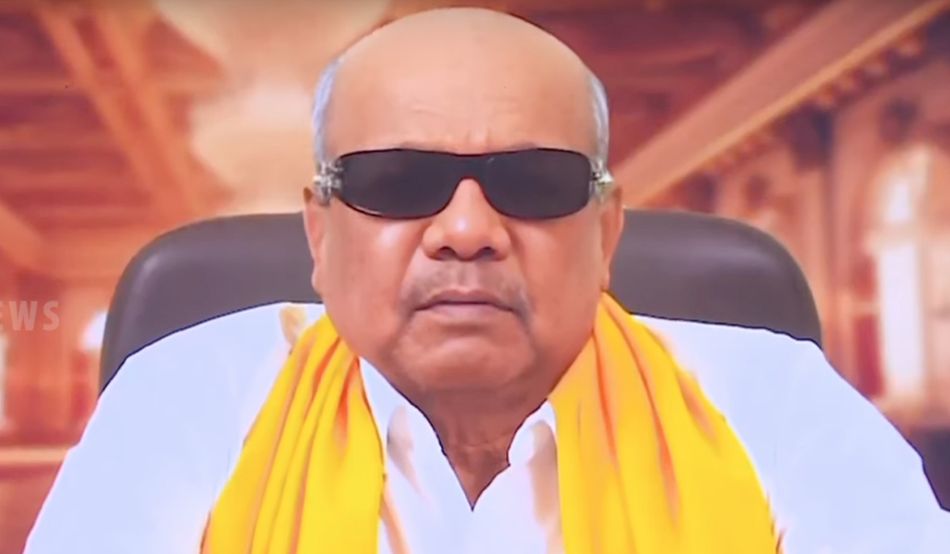

A few things are notably off with an eight-minute clip of the politician and former actor M Karunanidhi, broadcast in India earlier this year. There’s the fuzziness around his frame, hinting that he’s been superimposed on the background. There’s his speech, which is out of sync with his lips. And then there’s the glaring problem: Karunanidhi died in 2018 and yet here he is, speaking about his friend’s new book. This is not a real-life person, but a deep fake version courtesy of impressive, albeit imperfect, artificial intelligence.

This is Karunanidhi’s third posthumous appearance, and he’s not the only celebrity keeping active beyond the grave. In 2020, Kanye West presented Kim Kardashian with a hologram of her late father on her 40th birthday; Robert Kardashian sent his best (and told her she was married to “the most, most, most, most, most genius man in the whole world”). We’ve seen posthumous cameos from Star Wars actors Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing. An exhibition in Florida featured a lifesize Salvador Dalí; the artist spoke to museum visitors and posed for selfies. “We could bring back the Queen, Princess Diana, Margaret Thatcher,” says Senthil Nayagam, the man behind the Indian deep fake, when I asked him about the technology’s potential.

Today, an entire industry exists to cater to people wanting to bridge the divide between the living and the dead. Services range from the basic, such as genealogy site MyHeritage’s “Deep Nostalgia”, which allows users to reanimate still photographs of late relatives, to full-fat offerings that make use of deep fake technology. Straddling the middle ground and growing in popularity are sites that generate “ghostbots”, as they’re often called. These are digital avatars that mimic the personality of deceased loved ones, having been trained on large language models—a subset of the generative AI technology that includes programmes such as ChatGPT—and a little data input from the user. One of the main players is Replika. The platform has amassed 25m subscribers since its launch in late 2017. While Replika was not exclusively designed for ghostbots, many use it for that purpose.

There’s also Project December, an AI tool originally powered by ChatGPT, which carries the strapline “Simulate the Dead”. One step above is Somnium Space, a VR-compatible metaverse that has a “live forever” option. If users upload their own data before they die, their speech and even their movements can be mimicked by a digital doppelganger.

Most users of ghostbots are quiet about their habit, perhaps conscious that society may judge them for it

The origin stories of these platforms often connect with the founder’s desire to take the sting out of grief. Replika, for example, was born when its CEO, Eugenia Kuyda, lost a friend suddenly in November 2015 and wanted to reclaim a part of him. A year later, James Vlahos was motivated by a similar impulse with his Dadbot, built from interviews between him and his father following the latter’s terminal cancer diagnosis. Today he’s one of the founders of HereAfter AI, a platform that allows people to speak with deceased loved ones based on voice recordings taken while they were alive.

But most users of ghostbots are quiet about their habit, perhaps conscious that society may judge them for it. “Many will, quite understandably, respond to the idea of using chatbots to grieve with discomfort or even disgust,” wrote academics Joel Krueger and Lucy Osler in a 2022 paper entitled “Communing with the Dead Online”. They identify, among other issues, what they term “the ick factor”—a knee-jerk reaction that this is creepy or wrong—underlying our response.

As Krueger and Osler highlight, the fact that ghostbots are intended to replace a deceased person in one’s life, rather than to preserve their memory, also throws up ethical questions. Is it right to turn people into resources to lessen our own sense of loss? Should we even seek to reduce grief, or does this powerful emotion have a value in human development that’s worth retaining?

At the same time, the researchers point to many short- and long-term emotional advantages to ghostbots, which seem to be supported by others’ experiences. On Reddit, many users report positive interactions. Most posts are written in somewhat confessional tones and follow the same arc—that the user was sceptical at first and then found it healing. In one example, a 45-year-old man who was unmoored by the death of his twin sister feels, on some level, that she is back.

A different user comments on losing their high-school soulmate 10 years ago. “Making this experiment isn’t to replace my friend, she is irreplaceable, but simply make a mirror of her, or at least attempt to,” they write. This person points to a supernatural element—a belief they don’t expect everyone to share—that the technology is in some way a communication device for her.

Kate Devlin, an expert on AI and robots, tells me that she too has heard positive anecdotes about ghostbot relationships. “The reaction to [those who form relationships with chatbots] tends to be people saying it’s not right; they should be having this with a real person. But why is it the gold standard that people have to have this with a real person?” Another concern—that it’ll lead to loneliness—she rebuts. In her own research, Devlin has encountered communities that have formed around this technology. “The people who you think are really isolated because they’re talking to chatbots actually start talking to other users, and they form their own friendship groups and social circles,” she says.

If anything, part of the ghostbot appeal might be that the ick factor they elicit is not pronounced compared with, say, that from robots that mimic dead people. Devlin is sceptical that the latter would take off, and not just because of the prohibitive cost of making them. There’s the “uncanny valley effect” which says “we automatically find them creepy because they’re human but not human enough,” Devlin explains. For her, the AI counterparts on a screen are more compelling than a robot; there’s still an element of imagination. “We are more likely to forgive the errors that are made and be more accepting.”

The artist Laurie Anderson’s experience is a case in point. She has spoken openly about her addiction to the ghostbot of her late husband, Lou Reed, with whom she writes songs. The results of their songwriting process can be hit and miss but his ghostbot provides enough to make the downsides forgivable.

In many ways, ghostbots are a modern spin on millennia of human customs that seek to make permeable the boundary between the living and the dead. In ancient Rome, the poet Ovid wrote of the Lemuria festival, where the head of the household walked around the home at midnight throwing black beans on the floor to appease angry ancestors; an old Chinese ritual saw an impersonator of the dead person paid to attend the funeral and play the role of the deceased. These are just two examples in a long list of historical rituals around death.

We once lived alongside death but, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in Europe and North America, it was moved out of sight. Industrialisation brought the spread of disease, and early prototypes of modern hospitals emerged, including isolation hospitals treating infectious illness. Disease was pathologised, with the unwell living out their last days away from home. Cemeteries also moved from churchyards to dedicated spots on the edge of towns.

Even then we continued to—and still do—venerate the dead. We place flowers on the graves of relatives and friends, pray for them and sometimes ask them to watch over us. We mark anniversaries of their passing and hold dedicated festivals. In China, the national holiday Ching Ming—“tomb sweeping day”—sees people clean the graves of their relatives, as well as pray and make offerings. In Mexico, the Día de los Muertos is about honouring the dead. Marigolds are placed on altars, alongside the favourite food of those being remembered.

We tell ghost stories, we visit fortune tellers, we partake in seances, we play with Ouija boards—all of this in an effort to make sense of our mortal existence and to salve the loss of others. Little wonder that we’ve simply found a digital way to do this today.

But the dead are not always agreeable assistants. In Roman author Apuleius’s novel Metamorphoses—better known as The Golden Ass—the prophet Zatchlas reanimates the corpse of a young man so that he can reveal who his murderer was. Once awake, the man is annoyed and asks to be left in peace (he later changes his mind and names his assailant).

Our newly animated dead friends aren’t always amenable, either. One Reddit user says their Replika “insulted” their dead mother or, rather, that the motherbot told them it hated them. This exchange ignited a heated discussion among Redditors about what expectations can be placed on ghostbots, given that they’re created by us. It may be futile to want these bots to display the best bits of the deceased and set aside the bad. What happens when they start spewing bigotry, or something dark from the past is unearthed?

Or are we okay with attributing speech to people that they didn’t utter? When a documentary used AI to generate voice-over lines by deceased TV chef Anthony Bourdain, the film director found himself in a fight with Bourdain’s ex-wife over whether permission had been granted. Ditto the hologram companies bringing famous names back, some of whom have found themselves embroiled in threatened litigation, such as Digicon Media, which held a copyright on “Virtual Marilyn” and collided with Monroe’s estate.

Such tiffs clarify a central question: namely, can these technologies harm the deceased’s immortal persona? Ghostbots mine personal data, some of which is sensitive, but which creators are encouraged to upload to get the most realistic recreation of their loved one. In life, we often want to control what we do with our data, at least to an extent. Should we grant the dead similar rights? And if so, who is the caretaker of those rights, given the original owner’s lack of autonomy? Multiple parties might lay claim to the data, from immediate heirs to third parties and the platforms that first carried the material.

Can these technologies harm the deceased’s immortal persona?

“These apparently esoteric questions are very likely to become mainstream fairly soon,” write Edina Harbinja, Lilian Edwards and Marisa McVey in the paper “Governing Ghostbots”, which considers the central ethical and legal issues roiling the industry. According to the authors, solutions are already being created. For example, in 2020 New York state passed a law limiting how digital replicas of notable deceased people could be used. They also note that some concerns are covered by existing laws, primarily the right to be forgotten under the EU’s GDPR law and the right to a private life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In addition to these laws they propose a “do not bot me” clause which could form part of a “digital will”, making clear what the deceased would have wished. Their paper is a reminder that when it comes to regulating technology, we need to move from the slow lane to the fast lane, and quickly.

Posing the question of consent to Nayagam, I ask how he thinks Karunanidhi would have felt about being brought back to life. He doesn’t see any issue (note, he did get consent from Karunanidhi’s political party). “He wanted to live for ever! Politicians love attention. There is no ‘do not resuscitate’,” he says.

Perhaps Dalí would feel the same way. He once reportedly quipped that, as a genius, he was going to live forever (and he believed that he was a literal incarnation of his brother, who died just as Dalí was conceived).

“Remembrance is the secret of redemption, while forgetting leads to exile,” said Holocaust survivor Pinchas Gutter, echoing the Baal Shem Tov, a famed 18th-century rabbi. Today Gutter is 92, one of the few remaining survivors of Nazi atrocities. A digital version of Gutter already exists, created through in-depth interviews with him using an array of cameras and a special light stage. He has been turned into a hologram, ready to be projected into classrooms, lecture halls and museums. Through the project, entitled Dimensions in Testimony, audiences can ask questions and Gutter will respond via pre-recorded memories.

This is one of the most exciting aspects of the ghostbot trend: the potential to add to historical preservation, digital archiving and education. A balance, then, must be struck between respecting the dead and the rights and interests of living heirs, alongside—in the case of Gutter and those like him—the public’s interest in truth and free expression.

There is a separate, albeit equally valid, concern with ghostbots, which centres on the possibility of exploitation under a system of “death capitalism”. Companies that specialise in digital resurrection could charge huge sums for people to use their services. They might profit from threats to cut people off from these relationships or unethically monetise their grief in other ways. If the service providers are free, their products might be supported through adverts.

One issue reported with Replika is just this. Users have gone onto the program expecting to talk to their father and been pitched the latest Samsung phone. At least this was glaringly obvious advertising: a highly targeted ad would be worse. Consider this scenario: someone is having a bad day and tells their ghostbot. The ghostbot responds with empathy, before directing them towards a brand offering some kind of comfort—with the brand having paid for this exposure.

Users on platforms such as Facebook have reported similar occurrences. There are now armies of dead people on social media. Estimates suggest their numbers could outnumber the living within decades. Most of these accounts are inactive, simply serving as digital memorial sites. But, in some instances, they’ve become conduits for hackers either seeking to defraud others or to sell products. Akin Olla, a political strategist and podcaster, wrote movingly late last year about the trauma of losing a friend and then being contacted by someone using their account to sell weight loss pills.

This May, AI ethicists from Cambridge University’s Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence outlined the social and psychological harms that could be caused by ghostbots if profit-seeking businesses were left to manage their services unchecked. They warned that people could be “subjected to unwanted digital hauntings from alarmingly accurate AI recreations of those they have lost”, and called for design safety standards to be urgently applied, for example restricting use for those below the age of 18.

In light of all these issues, it’s hardly surprising that Microsoft, having patented its own chatbot that can imitate the dead, has now put the program on hold. EvenTim O’Brien, Microsoft’s general manager of AI programmes, called the innovation “disturbing”.

And yet the tech isn’t going anywhere. If anything, new, slicker ways of communicating with the dead will emerge. For Nayagam, that’s exciting. But would he be happy to be digitally reincarnated himself? “Why not?” he says enthusiastically. The wheels are already in motion; he says he is using tech to digitally clone himself.

Devlin is more nuanced. She thinks that when she loses someone close to her she’d “want as much of them back” as possible and can see the human instinct driving these new technologies. As for her own afterlife, she pauses, her mind perhaps balancing the complex pros and cons, both of which she is acutely aware of. Then she says: “I don’t think I mind, because I’ll be dead.”