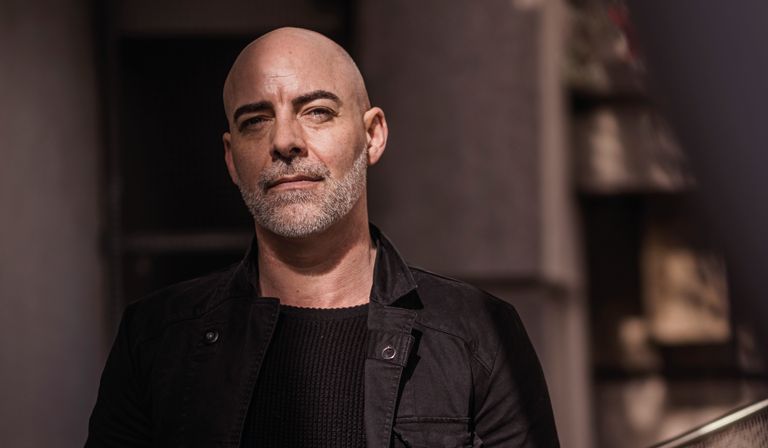

One night in November 2022, outside a members’ bar in London called the Century Club, a former tabloid journalist, Graham Johnson, was queuing to get inside a party crammed with famous people. Johnson, in his mid-50s, is pale and craggy—a sardonic Liverpudlian who tends to wear dark blue specs and big headphones which, when not in use, he keeps clasped around his throat like a necklace. Years ago, when Johnson was a keen reporter on the Sunday Mirror, and before that the News of the World, he might have appeared outside a celebrity-filled party such as this one without being invited. He might have come wearing hidden video equipment, his pockets stuffed with drug-testing surface swabs. Encouraged by a gossip-hungry editor, or egged on by newsroom colleagues, Johnson might have challenged himself to blag entry using clever backdoor means (dressing up as a caterer, say) before roaming the party looking for printable evidence of cocaine use. “Toilet cubicles first,” he once advised me.

This evening, though, Johnson’s name was on the guestlist. He checked his coat and plunged in. The Century Club had been hired out for the night by the actor Hugh Grant: open bar, posh canapés, a stand-up comedian making jokes that—same as the food and booze—came at Grant’s expense. This party had a dual purpose, serving as both a birthday celebration for the actor as well as a gesture of thanks to the dozens of people, Johnson included, who are involved in a movement to curtail the excesses of the British tabloid press.

Grant is a figurehead of this movement. His close friend Evan Harris, a doctor turned politician turned legal strategist, oversees the grittier courtroom work required to hold tabloids and their owners to account through civil litigation. In the past, both Grant and Harris have had their private voicemails intercepted by prying journalists—to use the accepted shorthand, their mobile phones were hacked. Grant was targeted with all the perverse force of tabloid editors at the height of their 1990s and 2000s belligerence; his personal records combed through by paid private investigators; his home burgled to order, apparently by crooks working in tandem with those investigators.

In their bid to police this kind of behaviour, and stop it from happening again, Grant and Harris have gathered around them some improbable agents of reform, including chastened investigators, aggrieved celebs, one senior royal out for revenge—and Graham Johnson.

Johnson’s role in the press reform movement is hard to explain: important, but oblique. Harris likes to introduce him as “the spider at the centre of the web”, a reference to the fact that so many of the legal claims related to press intrusion seem to have Johnson’s fingerprints on them. He is a tabloid apostate, someone who regrets aspects of his former career and seems hell-bent on making amends by bringing to light as much evidence of historical wrongdoing as he possibly can.

That night in November, Johnson pushed his way through the chattering crowd at the Century Club, passing lawyers, politicians and academics, as well as football managers, models, presenters, soap actors, film stars, comedians and chief executives. Many of them had had their phones hacked, back in those pre-WhatsApp days when after-the-beep voicemails were a popular means of communication. Johnson was fascinated by the incongruous pairings that Grant’s parties tended to throw together. Glenn Mulcaire, a reformed private investigator who spent time in jail for hacking phones, stood back-to-back at the bar with people whose most intimate secrets he had once helped into print. The actor Steve Coogan, also hacked, chatted with Alan Yentob, a former BBC executive whose voicemails used to be such a plentiful source of stories that his inbox was the first off-limits place at least one former reporter on the Sunday Mirror was taught to access.

That reporter, Dan Evans, was present at the party as well. He drank and gossiped with Nick Davies, whose investigations for the Guardian first lifted the lid on hacking, prompting criminal trials for several of Davies’s fellow journalists—Evans included. The pair had since made peace and become friends. If there was one thing that unified almost everybody present, Evans told me after the party, it was a sense they’d all “seen behind the Wizard of Oz curtain and witnessed the rottenness of the UK media system”. These reformers wanted to render useful change to that system, sure. But Evans made no secret of the fact that retaliation was a common motivator, too—in his case, against the tabloid editors and executives who had not yet been scrutinised to the same degree as their lower-rung employees. “That’s another overarching idea for the folk involved in the press reform movement,” Evans said. “This idea of ‘don’t get angry, get even’.”

* * *

One public figure not at the party, but apparently just as eager to get even with the British tabloid media, was Prince Harry. As guests drank and chatted, three legal actions involving Prince Harry gathered serious momentum in the UK courts: one action directed at the Mirror group of newspapers, one at the Mail group, and one at Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, which publishes the Sun. All three legal actions would have important preliminary hearings in spring 2023. Prince Harry’s witness statement in the Sun case contained especially explosive allegations that his brother, Prince William, agreed to a secret settlement with News Corp not to sue. After more than a decade of stuttering litigation—with countless billable hours expended in complicated legal manoeuvring, and more than 1,800 victims of unlawful press intrusion paid off to stop their claims from going to trial—there was about to be a series of public showdowns. Britain’s biggest, best-read, cruellest newspapers would be pitted against the single most prominent target of their badgering. Prince Harry had already indicated that he would not settle like his brother. He wanted his day in court.

People at the party were speculating. Prince Harry was looking more and more like a dangerous missile pointed at the heart of Britain’s tabloid establishment, so who stood in the possible blast radius? Piers Morgan, former editor of the Daily Mirror? Tina Weaver, of the Sunday Mirror? Paul Dacre, of the Mail titles? Rebekah Brooks, once editor of the News of the World and the Sun, now back running Murdoch’s powerful UK media empire? Johnson, no royalist, and inclined to be cynical about most people and most things, admired Prince Harry’s gall in standing up to these intimidating figures. “He’s got a bit of bottle,” Johnson said.

As part of his eccentric campaign against the tabloids, Johnson has self-published dozens of investigations into historic malpractice via a crowdfunded website he co-founded, Byline Investigates. He often passes new evidence he finds during the course of his digging on to victims of press intrusion and their lawyers—he calls this “letting the courts be my newspaper”, in reference to the fact that few tabloids or even broadsheets make use of his findings. Johnson has been out of steady journalistic employ for years. By plodding on, using skills he developed in tabloid newsrooms (not least perseverance, cheek and a skin as thick as a rhino’s), he has uncovered all sorts of compelling stuff, bits and pieces of which he has passed on to Prince Harry’s legal team. In a press reform movement characterised by strange alliances, here is its strangest: the prince and the pauperised reporter.

Not long after the party at the Century Club, while sitting in a pub on Fleet Street telling war stories about his hidden-camera, drug-swab days, Johnson explained to me that tabloid employees are proudest of their “stings”: those front page stories that discredit public figures, so-called because they come unexpectedly, they’re aggressive, and they fucking hurt. As 2022 turned to 2023, and the series of public hearings instigated by Prince Harry against the Mirror, the Mail and Murdoch’s News Corp came nearer, Johnson agreed to let me shadow him and his colleagues in their daily work. He said I could observe from close range what it looked like when a group of those stung by the tabloids banded together—and tried to sting back.

* * *

I first met Dan Evans for coffee a few weeks later. We sat in the lobby of a quiet hotel just south of Fleet Street. Evans is bearded, handsome, slightly weathered by stress, with an amateur boxer’s frame and the crouch of somebody who thinks they could be attacked at any moment. After thriving as what he called “a bit of a stormtrooper” for the tabloid press in his twenties, Evans turned whistleblower in his thirties. Now in his mid-forties, he is trying to make sense of a life cleaved in two: his woozy tabloid heyday and the subsequent hangover years. “For a while it was crisis after crisis,” he told me, “and the black dog beside me whenever I woke up. To be honest, I wasn’t always sure I was going to make it.”

Though the two men are not intimate friends, Evans’s background interweaves closely with that of Johnson: between them, the accounts of how their newspaper careers came to an end tell a vivid story about the hacking era in British journalism. After joining the Sunday Mirror in 1997, Johnson became investigations editor in 1999, working mostly on crime, doorstepping gangsters and other criminals, occasionally working the celebrity beat as well. In 2001, he was asked to contribute to a story about an actress who was supposed to be having an affair with a gangland figure. He was encouraged to intercept her voicemails. After listening to the actress’s messages over the course of a few days, Johnson complained that he felt grubby and refused to continue. He later came to realise his tabloid career had been doomed from that point. He left the Sunday Mirror in 2006.

Evans, a little younger, had badgered his way onto the same paper in 2001. “I turned up with a story about wind farms: not what the Sunday Mirror was looking for. But I was eager. I did their bidding.” In the weeks after 9/11, Evans was assigned to report on security at UK airports; he was sent undercover as a baggage handler. Successful in this, he was “soon buying drugs from train guards, hiring hitmen, nicking paedos… People on the outside look at this sort of work and think you’re ghoulish. You are ghoulish”. Within the tabloid ecosystem, however, “You learn to separate what happens in the office from reality”, Evans said. “You learn to depersonalise the work from the people you’re doing the work on.”

One day in 2003, he told me, he was taken aside by a Mirror group executive and shown how to dial in and listen without permission to Alan Yentob’s voicemails. Getting the gist, Evans soon had a PalmPilot—it looked and operated like a primitive iPad—loaded with the access information for hundreds of targets. Within a couple of years he was hacking ceaselessly, morning and night. As Johnson’s newsroom career declined, Evans’s was soaring. “I was producing a lot of stories. I was standing up [confirming] stories for others.” He said he was encouraged to use cheap disposable mobile phones, the better to avoid detection—often tossing these phones into the Thames when he left the office and went to the pub. “The idea was that we weren’t supposed to leave an evidentiary footprint. Though as litigation has since shown, we left behind something like a muddy field at Glastonbury.”

You learn to depersonalise the work from the people you’re doing the work on

In those days, whenever a tabloid story had its origins in an intercepted voicemail, it was the custom to attribute intimate details to a target’s pal. And often it was a friend who had unwittingly helped a story into print by leaving a few incautious words in a vulnerable digital inbox. People targeted in this fashion sometimes stopped trusting those closest to them. A particular cruelty of that era was that it produced stories so accurate that they were not only embarrassing or exposing, but also wrecked vital personal relationships.

Evans, interestingly, found that hacking was ruining his own personal relationships. He had moved to the News of the World in 2005 and was again deployed as a hacker—only now, like Johnson before him, he was starting to have moral qualms. The pressure was more relentless than at the Sunday Mirror. Andy Coulson was then the editor, as imposing and ruthless a figure as his predecessor, Brooks, who had moved on to edit the Sun. At the News of the World, if Evans ever tried to do any old-fashioned reporting, he said, the results were marginalised: “Just hack the fucking phones!” He drank and took drugs after work, at work, “neglecting relationships, anything normal that reminds you how weird your working life is. You get sadder and sadder and sadder”. The hacking era had completed a sordid circle, with even the perpetrators feeling thoroughly debased.

Then, in 2006, came the first police raids. Clive Goodman, the newspaper’s royal editor, was arrested, as was the investigator Glenn Mulcaire who had assisted Goodman in spying on staff at Buckingham Palace. Evans recalled being in the office at News Corp and feeling “sheer relief that the trouble was at Clive’s desk, not mine. The next morning we were told, ‘No more hacking.’” Evans personally destroyed evidence, burning documents in his mum and dad’s back garden, though by his own admission this was a hopelessly incomplete cover-up. He decided not to destroy a backup of the incriminating PalmPilot, “probably because there was a piece of me, on some weird-ass level, that wanted everything to come out”. In parts of News Corp, evidence was suppressed or destroyed, though it would take many years before the full scale of this activity came to light.

Evans said he didn’t hack again after the 2006 police raids—not until one bad slip in 2009. “I had been sent down to Swansea to do a story on a judge with a rent boy lover,” he recalled. “It made the front page. I remember my boss saying, ‘Great story. Don’t take your foot off the gas. We need something for next week’s paper.’” Evans went out to celebrate on the night before publication. “I woke up hungover, already in a bit of a panic about having no story for next week.” Lying in bed he read a short article in the Mail on Sunday about the romantic life of an interior designer, Kelly Hoppen. Before he swore off hacking, Evans used to know Hoppen’s number and the pin code to access her inbox. “I thought, ‘Fuck it.’ I called the number.” Something had changed. He couldn’t get through: “She’d set her security settings to super max.” Unnerved, “I did what anyone would have done. I scrubbed it from my mind and went back to sleep.”

Months later, lawyers for Hoppen got in touch with News Corp. They had traced Evans’s number. He took leave from the News of the World—under terrible pressure, he said, to keep quiet about his illegal activities. “It’s not the stuff you sign up for, with ambitions to be an award-winning journalist: you don’t imagine you’re going to end up carrying the can for some of the most powerful people on the planet.” The News of the World had started to come under attack from all sides. Nick Davies published his first Guardian stories about hacking in 2009, but it wasn’t until July 2011, when Davies wrote about the News of the World’s hacking of a phone belonging to Milly Dowler, a murdered schoolgirl, that everything toppled. Advertisers withdrew their support from the paper and it was almost immediately shut down by News Corp.

Evans—who pointed out to me that he had never hacked any victims of crime or their relatives—was arrested and released on bail. “The cops said to my lawyer, ‘If Daniel wants to talk, we’ll be listening.’” In legal limbo, close to broke, and fearing he was about to be set up as a scapegoat, Evans turned against his employers. He visited the police again and told them everything he knew. This outpouring of information took weeks. Between 2013 and 2014, when Brooks and Coulson faced their criminal trials, Evans gave several days’ worth of evidence at the Old Bailey. Coulson was found guilty and jailed for involvement in the hacking. Brooks was acquitted. Evans himself was convicted of crimes related to hacking. “I remember sitting in a bulletproof dock at the Old Bailey, thinking, how did I get here?” The judge gave him 10 months, suspending the sentence because of his testimony.

* * *

It wasn’t long before Graham Johnson had a criminal conviction of his own, albeit in more unusual circumstances. “Has he told you about his come-to-Jesus moment in a second-hand bookshop?” Nick Davies asked me. “Graham picked up a book of philosophy by Alain de Botton, of all people, and started reading. Something seemed to get through to him, while he stood there, that what he’d been doing for the tabloids was wrong.”

Davies guessed Johnson would have been able, like Evans, to win lenience in exchange for testimony. At one point, in 2013, Johnson met with officers who were by now investigating other accusations of unlawful information-gathering, this time at the Mirror group newspapers. Johnson had secured an agreement to help the police as an off-the-record intelligence source. During the meeting, however, he voluntarily overturned the agreement and offered to make a statement, on the record, about his involvement in hacking. “Among the many dozens of reporters who were directly involved in committing crimes for Fleet Street, Graham is unique—the only one who stepped forward on his own initiative and accepted prosecution,” Davies told me. “He’s tough. He once used that toughness to work ruthlessly for the tabloids. I wouldn’t want him showing up on my doorstep. Once he saw that what he was doing was wrong, that same toughness carried him in the other direction, towards bravery.”

Old-fashioned reporting was marginalised: journalists were told to 'just hack the fucking phone'

Appearing at Westminster Magistrates’ Court in 2014, Johnson pleaded guilty. He was given a sentence of two months’ imprisonment, suspended, and ordered to do 100 hours of unpaid work. During a break in court, Johnson was approached by Evan Harris, then a few years out of parliament—he had been a Liberal Democrat MP for Oxford West—and beginning his work as a paralegal consultant for hacking victims. Harris was also on the board of Hacked Off—a pressure group, formed in 2011, that agitates for tighter press regulation. At the time, the group was reportedly funded in part by Max Mosley, the wealthy motorsport magnate who, following a frontpage sting by the News of the World about his sex life, had sworn to exact revenge. (Hacked Off refuses to confirm that Mosley provided funding.) Johnson thought he knew just the sort of person Mosley was—“a warlord”, he called him, “and exactly the wrong person for the newspapers to fuck with.” Intrigued, Johnson took meetings with Harris and chatted with Mosley and others. A possible collaboration was discussed.

Harris had made similar approaches to Dan Evans, passing over a handwritten note on the day that Evans was sentenced at the Old Bailey. Johnson and Evans, both chastened poachers, were being sounded out. How would they like to try being gamekeepers, instead?

* * *

Evan Harris, clever and wordy, has an ex-politician’s relish for attention and a lawyer’s obsession with detail. In fact, he doesn’t hold any formal legal qualifications. When I asked how he would describe his work for victims of press intrusion, he suggested: “Strategist? Analyst?” He tends to wear jazzy lilac shirts under sober, slightly threadbare suits and often has the distracted expression of someone preparing to be obscenely late for their next appointment. Insofar as the movement for press reform has a base, in 2023, it is Harris’s tiny rented office in a building that overlooks Fleet Street.

In the back half of this office, hidden by a makeshift wall that’s been fashioned from stuffed ring binders, Harris tries to keep on top of hundreds of concurrent civil claims. (He is assisted in this work by a colleague, Dan Waddell.) In the front half of their office, Johnson sits at a desk facing the door, working on stories for Byline Investigates.

Whenever I visited Harris and Johnson in their den, it was a hilarious mess—half-empty mugs of instant coffee everywhere, a pile of decaying copies of the News of the World booted under a cupboard. On his desk, Johnson had a stack of old Mirror articles, the topmost headlined “I’M THE COLEEN PARTY FLASHER”. Everywhere I looked there was another memo, labelled box file or dog-eared celebrity memoir relating to allegations of tabloid spying.

And there were countless allegations. Take your pick: Beatles or Spice Girls, Atomic Kittens or Girls Aloud, footballers’ wives or footballers’ agents, EastEnders or Coronation Street: the famous now, the famous then, the famous-adjacent. It was not only celebrities and their associates whom the tabloids treated as prey. Relatives of those killed in the London terrorist attacks in 2005 were allegedly monitored illegally, even as they grieved. A former Labour MP, Paul Farrelly, told me he had seen evidence to suggest that he was spied on at the behest of tabloid editors—while he was sitting on a parliamentary select committee tasked with investigating criminal spying by tabloid editors. Another former Labour MP, Jim Murphy, had apparently been hacked while he was shadow defence secretary in 2011. According to evidence that emerged in court documents years later, Murphy initially called the police about the hacking. He then went out to dinner with an editor from within News Corp and decided on a course of discretion.

For the most part, claims of illegal prying at News Corp and the Mirror group have been kept discreet in a different way—muzzled with the use of cash. Florence Wildblood, a journalist who works for Byline Investigates and who tries to keep track of litigation statistics, reckons at least 1,845 claims involving unlawful information gathering by tabloid newspapers have been settled out of court since 2009. According to calculations made by Press Gazette in 2021 (on the 10-year anniversary of the closure of the News of the World), total hacking-related costs to Murdoch’s publishing empire then stood at over £1bn. Wildblood, working with available financial data up to the end of the 2022 tax year, puts the number at £1,233,210,400. The Sun, once a reliable money-making machine for Murdoch, ran pre-tax losses of £127m in 2022, almost £100m of that spent on covering damages and legal fees in ongoing hacking cases. Settlement costs for the Mirror group are lower but still eye-watering. Hamlins, a legal firm, says that compensation in the industry tends to range from a few thousand pounds “to significantly in excess of £100,000”—enough to make a tabloid executive blush, said Steve Coogan, who agreed to take £40,000 from the News of the World and “a six-figure sum” from the Mirror group.

Harris worked on Coogan’s case. He chose to base himself on Fleet Street because of its proximity to the Old Bailey, the Royal Courts of Justice and the civil-court complex in the Rolls Building, all short walks away. The major media organisations moved their operations from Fleet Street some time ago (News Corp to London Bridge, the Mirror group to Canary Wharf, the Mail group to Kensington) and if this famous old road has any material significance to those organisations in 2023, it can only be because of the expensive havoc wrought from Harris’s small office. From here, Harris and Johnson trade information whenever they are lawfully able to; Harris sometimes nudging Johnson towards newsworthy items that have emerged via the civil courts around the corner, Johnson passing on to Harris documents that are leaked to him by sources he has cultivated.

* * *

I sat with both Johnson and Harris one weekday in February, observing them at work and adding to their collection of used coffee mugs. I was interested to know more about how Johnson’s unconventional journalism was assisting in the current litigation. Could he give an example? Johnson frowned, thinking.

That week, he said, he had been contacted by lawyers for a former politician whose sexuality was once the subject of tabloid exposés. These lawyers were trying to gather evidence that the Mail on Sunday had sometimes paid for illegal spying work. They had read an article on Byline Investigates that suggested Johnson might be able to help. Could he?

He could. As we sat in the office, Johnson showed me the box file he had reached for when he heard the query. After flicking through pages with a wetted finger, he pulled out a photocopy of some handwritten notes made by Glenn Mulcaire about 15 years ago. The notes were related to Heather Mills, then the wife of Paul McCartney. “Mail on Sunday: £600” Mulcaire had written, alongside scribbled names, phone numbers and pin codes, apparently all belonging to Mills’s associates. Mulcaire, who has since become an ally of the press reform movement, confirmed to Johnson that this work—worth £600—had been subcontracted out to him by a man called Greg Miskiw on behalf of the Mail on Sunday. Miskiw himself, before his death in 2021, confirmed this fact to Johnson. (The Mail group has vigorously denied any involvement in criminal behaviour.)

In the Fleet Street office, Johnson laid an even thicker folder on the floor. He picked through more pages, finally pulling out copies of emails between Miskiw and someone from the Mail on Sunday. He also showed me handwritten transcripts of voicemails left by the actor Jude Law. Those transcripts, once obtained by Mulcaire and an associate he employed, were quoted by Miskiw in one of the emails to the Mail on Sunday contact. All of this Johnson passed on to the lawyers who reached out to him.

“So your Byline stories are a sort of shop window for lawyers?” I said. “If you like,” Johnson shrugged.

I sensed my question had caused offence—that there was much more to it. These days, Johnson is seen as a turncoat by several of his old newsroom colleagues. He has made enemies, as well, in the murky world of private detectives, and sometimes receives threatening text messages from them, though he dismissed these efforts at intimidation as the stuff of “plastic gangsters”. One day, looking wearier than usual, he told me that a group of vengeful hacks and gumshoes might be banding together to sue him. “And I know, if I withdrew my witness statements, stopped writing stories, stopped banging on doors, all that would subside.”

There are periods of his tabloid career—his early years at the News of the World in particular—that Johnson is deeply ashamed of. “I feel depressed, deceitful and dirty,” he wrote in a 2012 memoir called Hack, describing how he would invent stories for the Sunday paper. He once paid a flatmate called Gav a few hundred quid to pretend to be a neo-Nazi, for instance. “There was an ingrained culture of story fabrication at the News of the World,” Johnson wrote. “What a fucking knob-head I was [to take part]. But there you go.” Lately, representatives of the Mail group have dug up these old admissions and started repeating them, seeking to undermine him. They point to an email from 2016, in which a private investigator claimed to have been pressured and intimidated by Johnson to leak information. He denies this.

Whichever way you squint at his situation, Johnson cannot be said to be a conventional reporter. He shares a cramped office with a partisan legal strategist. His partner is Emma Jones, a former Sun journalist who sits on the board of Hacked Off. In recent years, Johnson has set up his own publishing company, Yellow Press, entering into agreements with some of his sources—the late Greg Miskiw included—complicating an always delicate journalistic relationship (and potentially gifting tabloid-group lawyers another way to traduce him). Despite the question marks, however, it is plain to anyone who meets Johnson that he is a gifted reporter, hungry, addicted to the risks and rewards of being out there with a notebook, digging up corporate secrets. He keeps doing this even though “the wordy papers”, as he calls them, don’t seem to trust him enough to run with everything

he finds.

There has been a marked decline in mainstream coverage of hacking cases since around 2014, perhaps because “justice had been seen to be done”, as Dan Evans wryly put it, following the conviction and jailing of Andy Coulson. So subdued is current reporting that it came as a shock to me to realise how many claims are still live in UK courts; at the time of writing, 162 involving News Corp, 113 involving the Mirror group. Though the alleged spying in these claims is largely historical (hacking pretty much ceased across the industry in 2011, when the News of the World closed), many claimants have only recently been made aware they were targets. Thousands, it is estimated, still don’t know. The employment and subcontracting of dubious private investigators by newspapers is a common practice that continues to this day. News Corp has never acknowledged criminal activity at the Sun, despite reaching financial settlements with those who say they were spied on illegally by the newspaper.

* * *

That February, as I sat with Johnson and Harris in their office, the Mirror group’s parent company was preparing a financial report in which it acknowledged putting aside another £30m to £50m to deal with “the total universe” of mounting claims. “Universe” was an apt word. In recent times, fresh legal actions have been brought against the British tabloid media by cricketer Michael Vaughan, director Guy Ritchie, singer Jarvis Cocker, jockey Kieren Fallon, Charlotte Church’s mum, David Beckham’s dad, and Paul Gascoigne’s friend Jimmy “Five Bellies” Gardner. In October 2022, six victims of serial press intrusion had banded together to make the first legal claim of hacking and blagging (impersonating someone with a view to obtaining private information) at the Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday. One of the six claimants, Elton John, alleged that his gardener’s phone had once been tapped by investigators working for the newspaper group. Another of the six, Baroness Doreen Lawrence, alleged that her bank accounts were snooped on. The Mail group denies these accusations. Preliminary hearings in the case were due to start in March.

We were discussing this in the Fleet Street office when a man called John Alford wandered in. Once a major target of the News of the World, Alford was here to discuss his case against News Corp. The 51-year-old, very much down on his luck, had once been a prominent actor in an ITV drama about firefighters, London’s Burning. During the 1990s, Alford was briefly a pop star, too, before a tabloid sting altered the course of his life. He was persuaded to supply a small amount of cocaine to undercover investigators. Their subsequent front page splash not only ended his career but put Alford in jail. As he sat down to join us, he noticed the yellowing copies of the News of the World and reminisced about the last time he appeared in its pages. “They put me in the final issue. Their top stings. Lording it up, right to the end!”

It was obvious Alford had endured some tough times. I knew from a Google search of his name that he was arrested in 2019 after fighting with police near his London home. Apparently intoxicated, he had shouted at the arresting officers: “Did Rupert Murdoch send you here to kill me?” Harris risked a joke about this as he and Alford discussed the latest in his case. It surprised me to learn that Alford had recently made a decision to settle. Instead of pursuing a trial, he had agreed to damages—after all he had been through. In fact, virtually all targets of tabloid hacking or blagging have settled out of court, even those people whose claims are plainly driven by belief in a cause. Grant and Coogan have settled in the past. Harris settled. Why?

There is such a thing as an offer a claimant cannot afford to reject

Because of the way civil litigation is arranged in the UK, Harris explained. Because of its oddly weighted risks and rewards. Because of incentives put in place to keep these disputes from clogging up courtrooms. “There is such a thing as an offer a claimant cannot afford to reject,” Harris said.

Everybody involved in hacking litigation has become wearily familiar with a certain ritual. Someone new will bring a claim against a tabloid. Perhaps a group of claimants will band together. After many hours of expensive preparation by lawyers for both sides, a case might get as far as a preliminary hearing, maybe several. Great bundles of evidence will have been assembled. Skeleton arguments, detailing the particulars of a claim or a defence, will have been drafted and redrafted. Dates for a warts-and-all trial might have been agreed. Then, before any such trial can take place—sometimes only days or hours before its commencement—everything is called off. Home time!

The claimant or claimants will have agreed to settle for, say, a six-figure sum, because if they were to risk going to trial, they might lose. Somehow worse, they might win, only to be awarded less in damages than they had been offered to settle out of court. In either case, they would be liable for costs. Because “costs tend to dwarf damages”, Harris explained, claimants are essentially blackmailed to settle. “You don’t want to lose your house in order to give millions of pounds to someone you hate… It means that if a wealthy defendant wants to avoid a trial, they generally always can, unless they’re facing a fabulously rich claimant. Unless they’re facing a claimant who won’t settle, whatever happens—a one-in-a-thousand claimant.”

Alford was not fabulously rich. He was not Harris’s one-in-a-thousand claimant. He still hoped to get a formal apology, though, and Harris was trying to help with this. The two men spoke some more, then Harris left Alford and Johnson to chat about football. It was almost afternoon. Sounds of muffled Fleet Street traffic drifted in through the window. A fan above the door hissed out air. Even so, it was stuffy in the room, and Harris took himself out to sit on the carpet in the corridor, a laptop across his knees.

He was keeping an eye on some big legal cases that were finally coming to the boil. These cases do have at their centre someone fabulously rich, that one-in-a-thousand claimant who might just be able to refuse a massive settlement. This claimant’s treatment by the British tabloids has been so wildly over-the-top, so relentless, the relevant paperwork relating to his cases wouldn’t fit inside the standard ring binders on Harris’s shelves. Instead, documents were kept in big cardboard boxes, each box marked in pen with a name: Prince Harry, Prince Harry, Prince Harry.

* * *

What were the odds of the prince showing up, one of these days, for a splashy courtroom appearance?

I pitched the question to Dan Evans over WhatsApp one day in March. He had researched it and, as far as he could establish, no British royal had ever given evidence in person at a British civil trial. As against that, few human beings—royal or otherwise—had been so thoroughly worked over by their national press. When they were working for the News of the World, Miskiw and Mulcaire colluded to track the young prince’s phone activity (he was a schoolboy at the time). Meanwhile, according to court-submitted evidence, the Mirror group employed at least 25 different private investigators to spy on Prince Harry over time—more if you include his associates. In interviews, Prince Harry has made plain his intention to hold the tabloid press to account for the hounding of his late mother and the bullying of his wife. So yes. He might one day want to sit in the back of a courtroom and watch his tormentors squirm.

Evans and I were sending each other WhatsApps, that day in March, to pass the time on a slow-moving morning of litigation. The Mirror group, still having to find tens of millions of pounds each year to cover its out-of-court settlements, appeared to have realised that it could not keep deferring trials indefinitely. Instead it would face some of the targets of its prying head on, before a judge, in a damage-limitation exercise. The question was, which victims? There were dozens with active claims: sportspeople, actors, singers. That day, in a boxy modern courtroom in the Rolls Building, a judge, Timothy Fancourt, had to decide which victims should be foregrounded in a coming trial, and which set aside.

If act one was the crimes, and act two was the Coulson trial, act three will be Britain getting the media it deserves

Names—some famous, some not—were bandied about by lawyers, Prince Harry’s among them. I sat at the back of the court, a few rows behind Harris and the solicitors and aides who had assembled to advocate for the claimants, none of whom were here in person. The claimants’ barrister, David Sherborne—a tanned, theatrical man who has spent as much time handling hacking claims as anyone has—did most of the talking. Evans, booked to appear as a witness at any eventual Mirror trial, kept an eye on the preliminary hearing via video-link.

It had been 20 years since Evans stood in a Sunday Mirror office and was taught how to hack Alan Yentob’s voicemails. It had been 14 years since he woke up hungover and tried to listen to Kelly Hoppen’s messages from his bed, 11 years since he agreed to collaborate with police, nine years since he joined the movement for press reform. It had been “a perpetual punch-up”, as Evans summarised it: a blur of depositions and debriefs, deepening pits of guilt, occasional bursts of catharsis. Since he came tumbling out of tabloid journalism, he has suffered periods of depression and had “several amazing therapists”. He had tried other work—everything from kitchen fitting to movie consultancy—before finding himself back as a journalist, co-founding Byline Investigates with Johnson and contributing regularly. He was still trying to square things with the people he hurt. As recently as Hugh Grant’s party at the Century Club, Evans had taken aside a hacking victim to say sorry.

As the hearing in the Rolls Building crept into another unimaginably expensive hour, Evans sent me a series of emojis. Horrified face. Wild-eyed, tongue-lolling face. Exploding-head face. He still couldn’t believe he had helped cause all this with his burner phones and his PalmPilot. Actually he was shattered, he had said to me on another occasion. He was ready to walk away, wanting to hang around only long enough to watch “act three” play out. “If act one was the crimes,” Evans explained, “and act two was that halfway house for justice that peaked with the Andy Coulson trial, act three will be about finishing the story. Act three will be the British media washing its face properly. Act three will be about Britain getting the media it deserves.” He paused for dramatic effect, before adding: “Of course, some might argue Britain already has the media it deserves.”

Successive Tory governments had bailed on a promise, made by David Cameron in 2011, to complete a full public inquiry into tabloid overreach and then act on its recommendations. After the initial phase of the inquiry led by Brian Leveson, which ended in 2012, there was supposed to be a follow-up, to examine more closely the troubling interdependence of the press and the police in the UK. That second phase, colloquially known as “Leveson II”, was initially delayed to leave fair room for the trials of Brooks and Coulson. When those trials were over, an argument was made that Leveson II was no longer relevant. The impetus behind it was finally lost in the confusion of a referendum, elections, several clownish leadership changes—not to mention ferocious lobbying by the press itself.

Frustrated by this, Evans had been beavering away on a project he called AltLev. He showed it to me one day, a Wikipedia-like website full of names, dates and colourful bubble-graphs. He clicked around, moving between legal documents that were technically in the public domain but were often hard for ordinary people to find and read. This website was a prototype. Since the death in 2021 of Max Mosley, a generous benefactor to the press reform movement, it has been harder for freelancers like Evans to fund these sorts of side projects. He was trying to secure enough money to launch AltLev as a free public resource, perhaps via crowdfunding. I asked him, why bother?

“Because every time there’s a hearing, loads of amazing evidence comes out,” Evans said, “evidence that the police or public inquiries [never managed to] get near. And there’s little to no reporting on it all. So it’s been out there, dying in darkness.”

During the course of reporting this story, different people showed me different examples of legal documents submitted to court. They may indeed have been dying in darkness but they were blinding reads if you were able to get hold of them, as grimly compelling as paperback Grishams. There was a 127-page skeleton argument, composed by Sherborne and his colleagues before a preliminary hearing against News Corp in 2017, that was broken up into segments with schlocky titles like “The Mulcaire Arrangement”. The document sketched out steps allegedly taken by News Corp executives to destroy evidence relating to their employment of Mulcaire, including the deletion of emails.

A later document, again composed by Sherborne and his colleagues ahead of a News Corp hearing in 2021, painted a colourful picture of this potential conspiracy, with pages and pages of rich detail. It told of swapped or lost hard drives, a luckless IT contractor (allegedly the target of a framing attempt) and a laptop that was discovered by police in an under-floor safe, “concealed underneath a vanity unit in an annex room which was only accessible from Ms Brooks’s main office”.

More recently, a 2023 court document laid out allegations that three former News Corp employees had received “significant settlement payments... after they amended their claims to allege the guilty knowledge of senior executives, including Ms Brooks”.

The most startling secret deal of all, which has also come to light in recent court papers, involved a “very large” payment to the future king, Prince William, to settle his hacking claim on the quiet. Filed shortly before this article went to press, these new papers included a serious accusation that Piers Morgan “knew about, encouraged and concealed” illegal newsgathering when he was editor of the News of the World in the 1990s. Representatives for the Mirror group have elsewhere made clear admissions that articles published under Morgan’s editorship of the Daily Mirror were sourced through unlawful means. This, despite the fact that Morgan has always denied involvement in anything criminal.

The more such documents you read, the more you wonder at the threat that Prince Harry might represent to Morgan, Brooks and others. If he were to become the first to refuse his wad of settlement cash, if he were to take one or more media empire to trial, all this evidence—teased out over a decade of quiet courtroom hearings—would be picked over, noisily, publicly, as the world watched.

Who knows what might result from such scrutiny? Harris is prepared to speculate: “The police, if they’re awake, might look and think, ‘That’s interesting.’ And maybe act.” Evans is excited by that prospect, but cautions that “the police are desperate not to take on this piece of business again. And the public might just agree with them—that it’s not important. I think it is important. Because ignoring it signposts that there are laws for normal people, and there are different laws for the powerful.”

The hearing in the Rolls Building was about to break for lunch. Lawyers for the Mirror group had been trying, with a chutzpah I found almost admirable, to persuade the judge to preclude Prince Harry from the coming trial. Wouldn’t it be better if another of the potential claimants—for instance, the comic actor Ricky Tomlinson—were foregrounded instead? There were wry smiles around the courtroom. This was the equivalent of suggesting that Lionel Messi be removed from the World Cup final, to be replaced with, well, Ricky Tomlinson.

The judge refused the suggestion. Prince Harry would get at least one of his trials after all. Dates were scribbled in everyone’s diaries for a months-long slug-fest, due to start in May 2023 and finish six or seven weeks later (after the publication of this article). The judge said he was prepared to prioritise Prince Harry’s claim over so many others precisely because he had made it implicit in public statements that he would resist settling. He would try to see this thing through.

There was further evidence of the prince’s resolve a few weeks later. A four-day session had been booked at the Royal Courts of Justice for the preliminary hearing in the Mail case involving Prince Harry, Elton John, Doreen Lawrence and three others. Like all preliminary hearings, it was bound to be slow and finicky, a test of everyone’s patience more than any sort of thrill ride. Nonetheless, ahead of days of relentless London drizzle, Prince Harry flew in from sunnier climes, sitting in court for three days to watch.

* * *

There were two dozen paparazzi in the café across the road from the Royal Courts of Justice, all sitting in a huddle after numbing hours in the rain, waiting for a glimpse of royalty. They fortified themselves on hot coffee, warm pastries and cooling stories of who had just seen Prince Harry do what as he entered court. “Did you see him give the double thumbs up?” said one pap to his mate, who asked in turn: “Did you see him grin when the car door opened?” These photographers didn’t know it but, earlier that week, deep within the Victorian London courthouse, they had missed a glorious image: Elton John, wearing yellow sunglasses, sat on an ancient public bench next to a dark-suited Prince Harry, the pair of them munching Pret sandwiches for lunch.

“It looked like posh cheddar for Elton, smoked salmon for the prince,” Johnson told me when I pressed him for gossip. By now I knew to expect that, whenever we met, Johnson would announce a new hustle or side-gig that was keeping him occupied alongside his guerrilla journalism. Once, he sat me down and spoke of plans to start an intellectual property empire: not only books but serialised stories, movies, all of it about tabloid rotters—an expansion of the hacking-verse. This week he had taken on a different role as ad hoc royal adviser. He was attached to Prince Harry and the other claimants who were suing the Mail, asked along to court by them to offer advice on key pieces of evidence he had turned up through his reporting.

Johnson was running late that morning, after trouble on the trains. While the paparazzi in the café ordered more coffee and began to submit their images for publication in tomorrow’s newspapers (the Daily Mail included), Johnson led me across the road to the courthouse. Passing through security, he remembered his chunky headphones, hurling them onto an X-ray conveyor belt in such a hurry that they came out squashed and misshapen. We rushed along polished corridors, passing through police cordons (“Legal team”, Johnson relished saying each time) before sneaking in at the back of a cramped courtroom. The hearing had been going on for about an hour already. In the bustle of late entry, it took us a few minutes to tune in and make sense of the dense legal argument that was under way.

There were a dozen court reporters sitting along one side of the room and as many observers perched on folding chairs at the back. Prince Harry sat between an aide and a publicist, sometimes passing notes to Harris, who sat in front of him. Once, when I asked Harris to explain why it had taken so long to bring this action against the Mail group even though there had been hundreds of equivalent actions against News Corp and the Mirror group, he pointed out that there was “no major whistleblower” from inside the Mail, no equivalent of Dan Evans, so litigation efforts had been halting. When I asked why that had finally changed, Harris credited the guts of these six claimants. And he credited Johnson, that determined, unthanked chaser-down of emails, invoices and confessions.

There was a focused atmosphere in the little courtroom. Everyone paid close attention as two barristers and a judge picked over a story that Johnson had once published. The story made allegations against one newspaper group, and the barristers and the judge were trying to determine whether some of the documentary evidence that Johnson had found in his reporting would one day be admissible in court. Sherborne, advocating for the claimants again, read out Johnson’s story sentence by sentence, as though testing it for strength. Around the courtroom, anyone in sight of a digital screen read along too.

I watched as Prince Harry scrolled through Johnson’s story using an aide’s laptop. Lawyers frowned as they read. Court reporters pouted. I glanced at Johnson to see what he was making of this extraordinary public scrutiny. He sat pale and impassive. As a journalist you crave being read, but this was being read to a whole different order. When Johnson caught my eye, he couldn’t resist a joke, leaning over to rasp in a deadpan whisper: “The prince has got his money’s worth out of me. All those years of paying taxes. Now this.”

Tabloid prying is an expression of one part of who we are

Time in the courtroom drifted by. Staring at the back of Prince Harry’s neck, I found myself wondering: would he have the stamina and patience to continue showing up at these hearings, to endure the length of time it would take to reach the end of the Mirror trial and see through his scraps with Murdoch and the Mail? Was he bored yet? Why did he keep tilting back in his chair and flexing his calves, as if trying to exercise? What would he order from Pret later, posh cheddar or salmon? People in the public eye are interesting. They just are! They draw the gaze, spurring curiosity, invited or otherwise. Tabloid prying is not something imposed on our society. It is an expression of one part, one not very attractive part, of who we are.

But because tabloid media organisations are plainly places where bullies can thrive, where excess is rewarded and where prudence is penalised, there have to be agreed limits on behaviour. Prying has to be underpinned by principles shared across the media industry. A decade ago, as the journalist Nick Davies reached the end of his exhaustive exposé of tabloid malpractice, he came across an email that was written by a junior editor working at the News of the World, back at the height of its criminal spying. “Sometimes I think we’re just dazzled by traces and checks and shady stuff,” the junior editor wrote, “and [so] we don’t try obvious journalistic techniques.”

Many hundreds of victims of hacking and blagging would never have received apologies, or settlement money, or closure, were it not for the obvious journalistic techniques employed by people like Johnson. Though the messy hacking saga has often been described as a case of journalism eating itself, it has also proved a funny sort of triumph for journalism in its pure form. Doorbells rung. Sources coaxed. Spiral notebooks filled.

Outside court, I collared Johnson one final time before he rushed off. He was at work on a new investigation that would involve surprising a career criminal at home. “I love a door-knock,” he said. Johnson was trying to make sense of a robbery from the 1990s, one possibly linked to a notorious tabloid sting of that era. Several of the people involved were dead, but Johnson felt compelled to chase down his leads regardless, driven by a compulsive curiosity that will urge on a reporter whether they have a newspaper to publish their discoveries or not. He had said to me, absent of editors prepared to back him, that he would use the courts as his newspaper. Today’s hearing was a fine example of how that might work.

Jokes about princes and taxes aside, what did he make of his story being read aloud in court like that? Was he nervous as it was probed by so many clever people for weaknesses? What was he thinking?

Johnson fiddled with his big headphones. He flushed a bit. “I was thinking, good story.”