Sue Carr was sworn in as the chief justice of England and Wales in October, the first woman to hold that post since the office’s inception in the 13th century. The news was warmly welcomed by another woman barrister who blazed her own remarkable path through the criminal justice system nearly 70 years ago.

Nemone Lethbridge, now 91, chuckles as she recalls how remote such an appointment would have seemed when she was first called to the bar in 1956. Such was the attitude to women barristers that at her first chambers she was told that because the men felt uneasy about sharing their “facilities” with a woman, she would be required to use the lavatory in a nearby café. She did this for the next four years.

“I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” she says at the home she shares with her son and his family in Stoke Newington, northeast London. “But I find that a lot of women had the same sort of experience even 20 years later.”

Lethbridge has led an extraordinary life. She has experienced the law at its very worst and its very best. She has seen close-up those most affected by it, defendants and victims, lawyers and lawmakers. She has defended and befriended some of Britain’s most notorious criminals. She was a pioneer, in more ways than one—and when we meet she has more than a few stories to tell.

A child of the Raj, Lethbridge was born in 1932 in Quetta, now in Pakistan, the daughter of a captain in the Bengal Sappers. Her father would later become the chief of intelligence in the postwar British Army of the Rhine and was a key figure in obtaining evidence for the Nuremberg trials. She was in Germany with him as a child during this period, and he took her to see the bunker where Hitler and Eva Braun had died.

She was educated in England, initially at a grim preparatory school where the headmaster was a creepy abuser. At her next, a Church of England school, she was a rebel. “Although I was baptised into the Church of England, I simply couldn’t tolerate an institution that had been founded by Henry VIII,” she says. “When everybody in my school was confirmed, I refused. I was a communist at the time and thought I was going to be the first communist prime minister of Great Britain.” But then she became—and remains—a practising Catholic.

She went to Somerville College, Oxford, and was one of only two women studying law at the university. Friends there included Ned Sherrin, later the producer of That Was The Week That Was, and Jeremy Isaacs, later the first head of Channel 4. “Ned used to take me out—I didn’t know he was gay, people were very much in the closet in those days.” Having graduated and passed the necessary bar exams by 1956, she sought work as a junior barrister and found to her dismay that this was a very male profession.

“What did disappoint me was the reaction of Gerald Gardiner, who went on to become lord chancellor in the Labour government. I went to see him and he said, ‘I’m very proud of you. I think you’ve done a wonderful thing. But I don’t take women in my chambers’.”

One of her father’s colleagues at Nuremberg, David Maxwell Fyfe (Lord Kilmuir), recommended her to the barrister Mervyn Griffith-Jones: “His instinct was to turn me down but his senior clerk had seen the letter from Kilmuir.” The clerk suggested that, while they might be obliged to accept her, she represented “an experiment which doesn’t have to be repeated”. He looked her up and down and insisted that she remove her nail varnish, telling her “this is the Temple, not the Palladium.” Griffith-Jones would later become famous for his role as prosecutor in the 1960 obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

One of Lethbridge’s first jobs was to appear for the Kray twins, England’s most notorious gangsters. She met them for the first time in the magistrates’ court in Stepney Green, accompanied by their redoubtable mother, Violet. They had been charged with attempting to break into cars. “I’m their mum, they’re innocent,” Violet informed Lethbridge. She was impressed that, even after a night in the cells, the twins were immaculately turned out and “Brylcreemed to glossy perfection”.

Ronnie Kray told her that car theft was beneath their dignity as he and his brother, Reggie, owned three clubs. He assured her that “we’re starring in the film of our life story, which is going to be directed by Joan Littlewood.” They were duly acquitted. (Later, Lethbridge attended, with the Krays, the premiere in Stratford of Littlewood’s hit musical Oh! What a Lovely War.) Thanks to the Krays’ network, she was never short of work. Initially she imagined that she was winning her cases because of her advocacy, but gradually realised it might have something to do with the regular presence of scar-faced heavies at the back of the courts.

Even after a night in the cells, the Kray twins were ‘Brylcreemed to glossy perfection’

One client was Frank Mitchell, later known as the “Mad Axeman” because he had held a couple up with an axe. “He was quite a sad person with a big, smiling, flat face. I took my little sister to Wandsworth prison with me to visit him. It was very naughty of me, I said she was my junior. He said, ‘The Krays have been so kind to me, they gave me a lovely watch and now they’ve sent me two lovely ladies,’ and then he kissed both our hands.” On this occasion, Mitchell had been charged with stabbing a fellow inmate. The Krays sat in the court when Lethbridge represented him and—remarkably—many of the witnesses said that they could not now be sure that it was Mitchell who had carried out the attack. He was acquitted.

To celebrate, the Krays invited her to their home in Bethnal Green, where Ronnie tried to press wads of £5 notes into her hand. When she explained she was paid by legal aid and couldn’t accept the money, they said they would get her a crocodile handbag instead—“the last thing I wanted,” she says. Mitchell was later murdered on the Krays’ instructions.

Another client was Ronnie Knight, then the husband of actress Barbara Windsor, whom Lethbridge secured an acquittal for on a robbery charge.

One evening in 1958, Lethbridge went to a pub in Belgravia with a friend from her chambers. “My friend said, ‘I want you to meet the most fascinating man in London’.” This was Jimmy O’Connor, who had been sentenced to death for murder in 1941, a crime he always denied. The death sentence had been halted at the last moment by home secretary Herbert Morrison, but he served 11 years and was now fighting to clear his name.

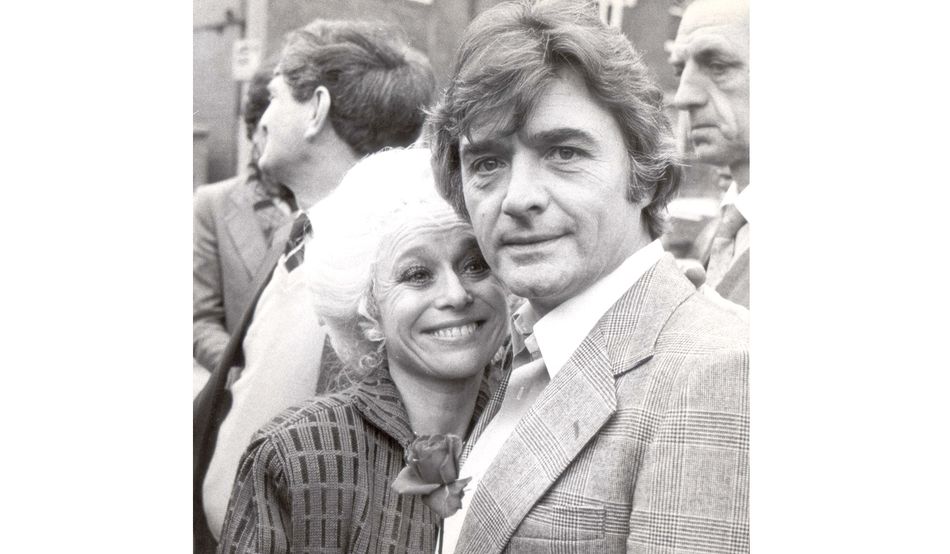

In her memoir, Lethbridge describes their meeting as Desdemona encountering Othello. “Not love at first sight but fascination at first sight,” she says now. “Jimmy was a great raconteur and very funny.” The pair married secretly in Dublin in 1959, but when the news became public, she was asked to leave her chambers and became a pariah in London’s legal circles.

She and Jimmy moved to the Greek island of Mykonos and had two sons, Ragnar and Milo. Jimmy had already established himself as a television playwright, thanks, strangely enough, to the encouragement of a former police officer. His first play commissioned by the BBC, Tap on the Shoulder, was directed by a young Ken Loach, who went on to direct several others, including Three Clear Sundays. This was about a man sentenced to death, and attracted 11m viewers. “He’s terribly nice and we’re still in touch,” she says of Loach. O’Connor was described in the Guardian as “perhaps the most important writer from prison since Bunyan.” Lethbridge says now: “I treasure that quotation.”

Lethbridge embarked on a playwriting career herself, and describes her 1966 television play The Portsmouth Defence as “a bit of a revenge on the bar”. It became a trilogy.

Lethbridge exuded the sort of charm, wit and engagement that must once have won over juries

When the Krays stood trial at the Old Bailey in 1969 for the murders of George Cornell and Jack “the Hat” McVitie, she and Jimmy were commissioned by a publishing house to cover it. “They wanted a book, but it didn’t happen because Jimmy and I fell out.” Their marriage ended because of Jimmy’s drinking and its effects, but they would later reconcile. He died in 2001, aged 83.

After the Krays’ convictions, Lethbridge kept in touch with Ronnie, visiting him in Broadmoor, the high-security psychiatric hospital, after he was certified insane. She recalls one visit: “the man who acted as Ronnie’s ‘butler’, dressed in a white jacket, came up to me and said, ‘would you like Assam or Earl Grey or PG Tips? And would you like a meat pie? They warm them up lovely here.’” Ronnie “had a boyfriend there and he asked me to do an appeal for him.” One time he gave Lethbridge “a teddy bear sewn by his own fair hands”.

We had first met in the Blind Beggar pub in east London, where Ronnie had shot Cornell dead. Lethbridge instantly exuded the sort of charm, wit and engagement that must once have won over juries and magistrates.

Lethbridge’s son Milo helped her to publish her memoir, Nemone: A Young Woman Barrister’s Battle Against Prejudice, Class and Misogyny, a frank and entertaining read that ends in the 1960s. She also wrote a book of poems, Postcards from Greece. One entry, “The Rent Boy’s Song”, is about Roy Cohn, who was counsel for Senator McCarthy in the 1950s during his pursuit of communists and later adviser to a young Donald Trump. They met on Mykonos in the 1960s. “He was a very nasty piece of work who would take out famous women in America but come to Mykonos in the summer to pick up blonde boys in his white Jeep.”

Who were the greatest barristers? She says Jeremy Hutchinson “was the best, very funny, very effective”—he defended Soviet double agent George Blake, Christine Keeler of the Profumo affair, great train robber Charlie Wilson and drug smuggler Howard Marks. George Carman, who defended Jeremy Thorpe and starred in countless libel cases, “was very good”. Victor Durand “had a beautiful speaking voice” and Jean Southworth, who had been at Bletchley Park during the war, “was very good and never received the recognition she deserved.”

Despite the playwriting success and work for BBC Two as a television presenter in the 1970s, Lethbridge wanted to return to the bar. “It was 18 years before I could.” She then represented Winston Silcott at the Old Bailey, who was applying for bail in a murder case; he was later charged and eventually cleared of the murder of police constable Keith Blakelock in the 1985 Tottenham riots. With another barrister, she helped to found the Our Lady of Good Counsel Law Centre in Stoke Newington in 1995. It’s open for walk-ins on Saturday afternoons, and she still gives advice there every other week.

“It’s a vale of tears now,” she says of the legal profession. “When they had their strike the average earnings for a young [criminal] barrister were £12,200 a year. It really frightens me because, in 30 years’ time, who are going to be the judges? It means that only people with a rich daddy or a private income can do it now. It’s going right back to Victorian times. I just detest this government.”

Her days with Griffith-Jones have now led to a tradition for women barristers. “One day I was going to the Old Bailey with Mervyn in his Jaguar. I had a nice pair of pink kid gloves which my mother had given me. He looked down at my hands and said, ‘Pink gloves, Nemone, at the Old Bailey!’ I had to take them off —only white or black! A few years ago, Katie Gollop KC thought this was very funny, so she went and got some long white gloves, now known as ‘the Lethbridge gloves’. Every year they have a raffle for the new women ‘silks’ [King’s Counsel] and I’m allowed to pick the recipient [of the gloves] from the hat. The new batch of women silks are very impressive, very forward-thinking.”

She is busy on volume two of her memoirs. With the criminal justice system in catastrophic disarray, what better time for Lethbridge, who confronted the legal profession’s failings decades ago, to tackle them once more—gloves off?