Democracy and the rule of law are intertwined and they are both under serious threat. The international community is in a bad place and Britain is far from immune to the strains.

Baroness Helena Kennedy KC, the renowned lawyer and human rights activist, paints a bleak picture of the world she is consistently fighting to improve. When I sit down with her in my study in my London flat, the tragedy in the Middle East is yet to unfold but will begin within weeks. Kennedy points to growing authoritarianism in countries including Hungary and Turkey. She is emphatically “outraged” over the UK’s recent Illegal Migration Act and sees the US polity as heading for disaster. Kennedy reserves some of her angriest strictures for China and Russia. A fervent believer in the rule of law as a force for good, she has no illusions about the ways these countries invent their own so-called laws to give them cover for their illegal actions.

Yet she is not giving up. Kennedy, a social democrat and long-time Labour Party member, remains fiercely committed to the causes closest to her heart—the safeguarding of human rights, equality for women, freedom of speech and media independence. She urges democracies to band together in defence of their institutions and the rule of law.

What does it mean to defend these values in an increasingly unstable world, when it can sometimes feel as though everything is moving in the wrong direction? And how far can the law go in righting wrongs on such a scale?

These are some of the questions in my mind when I meet Kennedy and she is certainly well qualified to answer them. As a barrister with 50 years’ membership of the prominent Doughty Street Chambers (which she helped to open), she has defended many victims of discrimination and violence. She has acted in cases including the Brighton Bombing and Guildford Four Appeal. As a Labour peer, the House of Lords gives her an influential platform to defend her causes.

In her latest role, she is now running the Human Rights Institute established by the International Bar Association. This vantage point allows her to draw attention to violations of human rights, as well as bring practical help to victims of discrimination.

The latest international human rights tragedy has now unfolded in the Middle East and I ask for comment. Kennedy is unequivocal in her “outrage and condemnation at Hamas and the atrocity crimes committed in southern Israel. I loathe the ideology of Hamas, and have seen up close the poisonous grip of Jihadism on young Muslims when I acted in terrorism cases like the transatlantic bomb plot here in the UK.” She has no doubt that “Israel has a right to self-defence. But it has to be proportionate and in accordance with international law.” Kennedy warns against collective punishment and refers to Gaza “being reduced to rubble”. Though token amounts of aid are now being allowed in, she condemns Israel’s actions to cut off supplies of water. “Water is a basic human right and its denial violates international law. It is a war crime.” She adds: “When people ask, ‘are you pro-Israeli or pro-Palestinian?’, I say I am pro-human rights.”

Rather than helplessly watching international conflicts develop, Kennedy has taken action, seeking to protect Afghanistan’s women judges, many of whom she helped to flee their homeland as the country fell back into Taliban control. And she has now taken on yet another role as co-chair of a new task force to establish an effective legal mechanism for the return of Ukrainian children forcibly taken to Russia.

Earlier this year, in the Great Hall of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, there was a large gathering of Britain’s legal elite together with senior, mainly Labour politicians and the media. They had come to celebrate Kennedy’s birthday and her 50 years of service at the Bar. They were joined by friends from all corners of the world and of course by her family, including her three children and husband Iain Hutchison, equally distinguished in his own field of medicine. An Afghan woman judge, who had recently reached Britain thanks to Kennedy’s efforts, was among the handful of speakers whose remarks reflected not just admiration for her achievements but also emphasised her warmth and generosity and humour.

Helena is a long-standing friend, which perhaps makes me somewhat partial as an interviewer. I have always found the range of her activities quite mind-boggling. At the age of 73 there is no sign of slowing down—and every sign of speeding up—her work commitments. A little while ago I persuaded her to pause for an informal chat about “the way in which the pendulum seems to have swung so far to the right, not just inside the United Kingdom, but globally.”

“It’s just become shockingly desperate that so many places, even places that call themselves democracies and respecters of the rule of law, have been prepared to ride roughshod over international treaties, over laws that protect minorities, protect women and protect media freedom.

“There is a trajectory that takes place as governments move to the authoritarian right,” she explains. “The people who become leaders in authoritarian countries tend to be narcissist men incapable of accepting criticism, and don’t like opponents. And the nature of democracy is that you have an opposition that is going to hold you accountable. They go after opposition leaders and often will jail them on trumped up charges. They go after journalists who are holding governments to account and exposing abuses of power. And they go after lawyers and judges, and so you see an erosion of the rule of law.”

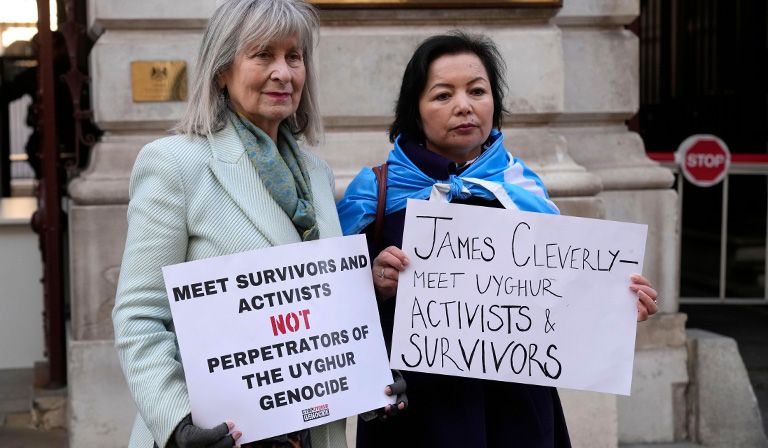

Kennedy cites the imprisonment and intimidation of opposition leaders and lawyers in Belarus, and speaks of Russia and China as the crassest examples of totalitarian regimes turning law “from being a protector of human rights into an instrument for the abuse of human rights.” She has been sanctioned by China herself—her husband and children have also been put on the list— “simply for raising the horrors of what is happening to the Uyghur people, who are absolutely at the receiving end of grievous crimes against humanity. Their culture is being destroyed. Women are experiencing sterilisation and being pressurised into abortions. We should be thinking carefully about how we trade with China.” She is scathing about multinational corporations who have turned a blind eye to the horrors in Xinjiang. “They are making huge profits at the expense of the Uyghurs.”

The conversation turns back to the root causes behind the erosion of democracy. Kennedy identifies a number of factors. “The big shift after the end of the Cold War, to a full turbocharged market system everywhere, has led to an incredible gulf between a substantial minority of ultra-rich billionaires and ordinary folk. That inevitably creates the seeds of conflict. You get promises of solutions to complex problems that are simplistic and unrealistic. So you look for a new scapegoat to blame for the ills of society.” Where Britain is concerned, the choice scapegoat was the EU, wrongly blamed for Britain’s economic decline and regional inequality.

This line of thinking prompts Kennedy to condemn the austerity policies implemented by former chancellor George Osborne. She has no doubt that the moves to shrink government led “to a huge reduction of social programmes that are vital to a good society. Suddenly there was powerful momentum behind a neoliberal economic strategy that has marginalised the least well-off in our societies, and tries to convince them that their problems are caused by foreigners taking their jobs and using public services.” Of course, Kennedy recognises that mass migration presents huge challenges, and that the climate crisis may make these even worse. She is emphatic that this has to be seen as a Europe-wide problem and cannot be addressed on narrow national terms. She almost runs out of words in condemnation of the British government’s attempts to deal with immigration unilaterally.

Not that she claims any glib answers to the crisis. “If you ask me, the answer doesn’t trip off my tongue. But solutions can only be found by collaborating with other nations to draw up a long-term strategy.” She doesn’t rule out a revision of the UN Refugee Convention. “It may be that you have to create a different formulation with regard to those responsibilities for refugees. But you are only going to do that with the goodwill of many nations working together. And you don’t do it by little Britain going off on its own.”

For good measure, she stresses that this is payback time: “Our standard of life has been greatly enriched by some of the disadvantages the poor countries have had to face”, and in her view “the rich world is still being hugely exploitative of the wealth of Africa”. She is referring to powerful multinationals and their government backers competing for deposits of rare—and, in today’s industrial world, essential—minerals and raw materials.

“We have to do something about the greater sharing of the world’s resources and the sharing of the world’s problems.” She sharply condemns what she describes as the “outsourcing of our problems” and thunders against the British government’s attempts to send migrants to Rwanda, a country which she describes as “still suffering from the consequences of genocide.” She describes its President Kagame as a “human rights abuser”.

Kennedy doesn’t rule out a revision of the UN Refugee Convention

Kennedy is now in full flow. Our conversation jumps to the United Nations in New York. Her current job with the International Bar Association takes her there quite frequently. She does not belong to the school that argues the UN has had its day. But she believes that the UN was severely damaged by the Trump administration and needs reform to validate itself again. She mentions a proposal for an International Court of Anti-Corruption, but sees no takers. “I think the UN could be much more effective and bolder…. But if you seek to reform when a large number of nations, including all the most influential nations in the world, are authoritarian or have authoritarian inclinations, then you might get something less than you already have... You can’t have reform unless you have a reform-minded world.”

The conversation moves on at breakneck speed. I press her on the culture wars. But she resists diving deeply into this controversial debate. She recognises that there are problems of free speech, especially in the universities. She believes that students have every right to demonstrate and protest. But “I certainly don’t want people to be prevented from speaking, especially not when the context is about violence against women.” She asserts that right-wing political forces are deliberately fuelling the culture wars: “Let’s be clear. Culture wars serve the interests of the right. They are being encouraged by a government that has run out of steam. They are making great use of people’s anxieties around, for example, trans women.”

Kennedy has a long history of helping trans women in legal cases, going back to 1995 when she fought a discrimination battle in the European Court of Justice. “Since then I have followed very closely the experience of trans women. I have often acted in cases, particularly when trans women have been raped just as viciously as heterosexual women. The discrimination suffered by trans women is enormous. So I want to see protection for trans people… However, I don’t like the hostile debate around it and I think it should be dialled down, and [we should seek to] have a better kind of conversation.”

Let’s be clear. Culture wars serve the interests of the right

Perhaps to avoid any misunderstanding she issues a reminder. “I am a feminist, and I have been arguing for women’s rights and have been at the forefront of reforms that work for women during all my professional life.” Society today still puts “a terrible burden… on the shoulders of young women. And the young women are now saying ‘no’ and they are quite right. And they have my support. What’s happening to women is unfinished business. We still haven’t got equality for women.” To see that, you need only look at America’s Supreme Court, which “really has been captured by the extreme right.” The Court’s anti-abortion ruling was an assault against the idea “that women would be able to take their own decisions over their own reproductive system.”

Having roamed over a range of political and social issues, pessimism has prevailed. But there is an exception. Young people give Kennedy cause for hope. “While I may sound rather hopeless about all of this, spending time with students in the universities can be very uplifting. The young are our main hope for change. And the young want that balance of freedom that people should be able to live as they want.” By this she means that, unlike earlier generations, “young people today are embracing people’s right to be able to live as they want, and so they are not hostile to people because of race or because of their sexuality.”

Kennedy was brought up in a Glasgow tenement and succeeded in securing a first-class education. Unlike this generation, she went to university without having to load herself up with debt. “The young have it much harder now. Yet at the same time it has made them much more resourceful. Many of them have a much clearer view of how society works. They are also much clearer about the challenge and threats of climate change, and how societies need to deal with that. I always feel uplifted when I spend time with the young.”

She continues: “I had always imagined that by the time I had reached the age I am now the world would be in a much better place. And I have loved my life in the law.” Though it can be used for unsavoury outcomes and have cruel effects on people’s lives, “I also know it can be used and leveraged for good purposes. Law is one of the instruments that have to be harnessed for change.” As Kennedy sees it, “societies do need rules by which we live together, but they can’t be too constraining.” The challenge is to get the right balance.

“I believe there are cycles in our histories. So I don’t feel hopeless about the future. But I do feel I might not be around when the good society comes to fruition. The creation of good societies is not pie in the sky. I believe it’s possible. But,” and here comes the sting in the tail: “people have to stop enriching themselves at the expense of others.”

And the key to it all? “The rule of law. Justice matters.”