As prisons in the United Kingdom go, HMP Coldingley in Surrey ranks somewhere in the grim middle. It is not one of the crumbling Victorian-era hellholes that make up about a third of the prison estate, but it is showing its age. Opened in 1969, it is a noisy maze of cold, dark cells, broken windows, shabby common areas and communal toilets. In some wings, according to the most recent government inspection in January 2022, “waits to use the lavatories were so long that prisoners often had to revert to using a bucket in their cell.” Levels of violence, the inspector reckoned, are “around average”, which is to say, frightening; they are largely associated with control of the prison drug trade. Work and education opportunities for inmates were deemed “disappointing”. On the brighter side, staff-prisoner relations were rated “excellent”.

Most of Coldingley’s 500 or so residents are serving long sentences, making it an appropriate location for a special event called Lifer Day. On an overcast Thursday in March, some of the country’s leading prison authorities convened on a stage in the prison’s nondescript chapel. The day-long gathering was intended to improve morale and help inmates navigate the frustrations that come with a life sentence. (In the UK, as in the US, “life” usually means the offender has a prescribed minimum “tariff”, after which he—the prison population is 96 per cent male—can be set free by a parole board, though he will be subject to some level of supervision for the rest of his days. Life without the possibility of parole—what Americans call LWOP and Brits call “whole life”—is far less common in the UK than in the US. At least, so far.)

The luminaries who came to speak at Coldingley—most of whom had decades of experience of the system—included longstanding parole board members, a retired Crown Court judge and the heads of two leading prison reform charities, the Howard League for Penal Reform and the Prison Reform Trust.

Two shifts—about 50 lifers each, one after the other—organised themselves on folding chairs. They questioned the experts about new procedural hurdles the government has erected for lifers who hope to graduate to less restrictive conditions—either an open-category prison, where the facility may authorise furloughs to spend time with family or at a job, or a “progression regime”, which allows inmates to earn greater freedom step by step.

Much of the discussion revolved around efforts by Dominic Raab, the justice secretary at the time, to restrict access to more liberal facilities. Last summer, Raab declared that he would veto any transfers that were not designated “essential”, or that might “undermine public confidence”. He didn’t define his terms, but he left no doubt of his intent. Before he asserted his new powers, offenders who could present evidence that they had been rehabilitated had a greater than 90 per cent chance of moving to less restrictive custody. Since Raab’s intervention last June, 90 per cent of requests had been denied. A bill currently at the committee stage in parliament proposes to expand the justice secretary’s power further, authorising him to overrule the parole board not just on where prisoners serve their time but on when they can be released, which is pretty much the board’s main job. (Raab resigned the following month in the face of accusations that he bullied his staff. His successor, Alex Chalk, served briefly as minister of state for prisons, parole and probation and has a reputation for being more centrist. He declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Inmates I talked to on Lifer Day were grateful for the sympathetic hearing and the chance to vent. A few picked at leftovers from the Marks & Spencer sushi lunch ordered for the visitors after the morning session. No one expressed any confidence that the political climate, with or without Raab, would favour an improvement of their situation. One lifer who is 13 years into a 22-year minimum term told me that the Lifer Day gathering “just brings back to the forefront of my mind the plain truth: that we’re fucked.”

As a late-in-life student of American criminal justice, I want to be a little humble about throwing stones at the UK’s penal system. It is hard to imagine a system more perfectly designed for failure than ours in the US, which in the name of “corrections” helps perpetuate a cycle of poverty, crime, community dysfunction and despair. The UK (for this discussion, England and Wales; Scotland and Northern Ireland operate separately) locks up a larger percentage of its subjects than its neighbours in western Europe, but its per capita incarceration rate is only about a third of America’s. While the UK, like most democracies, long ago abolished capital punishment, the US put 18 prisoners to death last year and has about 2,500 more awaiting execution. The US also has an insane gun culture, on both sides of the law. And there is no equivalent to His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons, the independent agency that conducts unannounced, in-depth inspections and publishes the often harrowing findings.

But an American journalist exploring the UK’s version of punishment hears many echoes of American dysfunction, and they are growing louder: overcrowded cell blocks, low staff morale, violence and self-harm, rampant drug use and mental illness, a severe shortage of rehabilitative activities and a parole system widely described as an abject failure in safely reintroducing prisoners to the free world. As in the US, the UK’s incarcerated population is disproportionately black—about 13 per cent of those behind bars compared to 4 per cent of the population at large—and inmates of colour find the system suffused with racism, subtle and not so subtle.

And while the US has—in the past decade or two—begun to reduce its incarceration rate; spawned reform movements on the left and right; elected several progressive prosecutors; restored college grants for incarcerated students and created tentative pockets of innovative prison management, the UK seems to be drifting in the other direction. Sentences in England and Wales are growing more draconian, driving up prison populations; experienced staff are jumping ship; opportunities for self-improvement are shrinking. And prisons that locked down the cell blocks for 23 hours a day during the pandemic have been slow to let inmates out of their claustrophobic cages now the crisis has passed.

More prisoners than ever will have left custody after spending almost their entire sentence locked in their cells

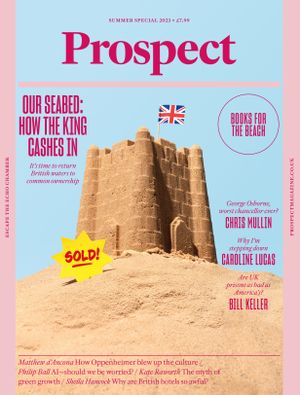

Neither the ruling party nor the opposition has made reversing these trends a priority. If you want a hint of the likely level of discourse in the run-up to the next election, consider Labour’s recent attack ad smearing the Tory prime minister as soft on paedophiles. (“Do you think adults convicted of sexually assaulting children should go to prison? Rishi Sunak doesn’t.”) To an American, this is the familiar, performative approach to crime-fighting that panders to voters’ fears without actually making the country safer.

John Podmore, whose nearly 40 years of engagement with prisons include service as an inspector and governor, laments above all what he sees as a pervasive public indifference. His 2012 book flayed UK prisons for failing to fulfil their fundamental mission; its title, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, seems more apt than ever. (It could also be the motto of the Ministry of Justice press office, which refused my requests for help arranging jail visits.)

“I’m more pessimistic now than I think I’ve ever been,” Podmore tells me. “The pendulum is swinging in the wrong direction.” I hear similar dismay from executives and staff at the four prisons I manage to visit without the ministry’s blessing, from parole board members, charities, defence solicitors, reform advocates and, of course, prisoners themselves.

One senior prison official, when asked how the system has evolved during his three decades of service, slowly shakes his head. “‘Evolved’ implies improvement,” he says. “The service has certainly changed, but not for the better.”

How do you measure the success or failure of a prison? If you are a warden, your first priority is keeping control. Riots and escapes can be career-enders in a prison service. But control of a facility tells you little about what happens after prisoners are released, as the overwhelming majority will be.

If you are a criminologist, your principal metric is more likely to be recidivism. What percentage of prisoners who re-enter the free world commit new crimes? This is a useful but imperfect measure; most crimes are never reported, most reported crimes are never solved, and sometimes the recidivist’s new “offences” are minor violations of parole protocols—a dirty urine sample, a missed curfew—and pose no great threat to public safety.

If you are an ordinary citizen, you probably have a general sense of whether your neighbourhood is safe, though this may be based as much on hyperventilating media coverage and politicians’ fear-mongering as on crime data or actual experience. Despite sharp increases in sentencing severity since 1996, and despite much evidence that stiffer sentences do not stop crime, polling consistently shows that most people in the UK believe that punishment should be harsher.

The inspectorate of prisons has a more comprehensive scorecard that acknowledges society’s legitimate desire to punish those who break the law while emphasising measures that encourage the punished to lead productive lives when released. It grades facilities in four categories: safety, respect, purposeful activity and planning for rehabilitation and release. These are judged to constitute the essentials of a “healthy prison”. Safety includes not just recorded episodes of violence but the adequacy of physical and mental healthcare. Respect means staff and inmates treating each other as fellow human beings, including such courtesies as responding to appeals and complaints. Purposeful activity includes access to education, exercise, skills training, arts and behavioural counselling. And each prisoner is expected to have a plan to prepare for and cope with life after release. Reports also include a general appraisal of a prison’s leadership.

The inspectorate’s July 2022 nationwide overview runs to 134 pages and portrays a system in distress. Even discounting the added challenges of the pandemic, most prisons fell far short of the basic expectations of a “healthy prison”.

The shortcomings start with the perennial problem of infrastructure. Thirty-two of the 122 prisons in England and Wales date back to Queen Victoria’s day.

“Buildings are crumbling, the showers don’t work, ventilation is poor, prisoners don’t get enough exercise,” Charlie Taylor, chief inspector of UK prisons, tells me when I interview him in February at his office in Canary Wharf. “Look on Google Earth at the old prisons like Wormwood Scrubs and you see a cramped space with not much room for exercise, workshops or education.”

Newer prisons with more expansive grounds tend to be overcrowded as well, with many prisoners sharing cells meant for single occupancy. Most facilities have been plagued by staff shortages. The service has never fully recovered from austerity budgets enacted between 2010 and 2015 when annual prison spending was slashed by 21 per cent. Then Covid-19 brought an exodus of personnel fearful of what a lethal infection can do in a closed environment. (You can’t police a prison cell block on Zoom.) When the job market rebounded after the pandemic, many prison officers sought safer work and better pay as police, Border Force officers or transport workers. Brexit curtailed the recruiting of prison staff from across the Channel.

Edwina Grosvenor is a philanthropist, criminologist and podcaster whose projects include The Clink, a charity that supports high-end training restaurants inside a number of prisons, and an alternative housing community for women offenders. She says the staffing problem has crippled efforts at rehabilitation. “I talked to a governor who lost four people on the same day, amounting to 100 years of experience,” she tells me. Governors have told her that as many as 80 per cent of their staff are 24-years-old or younger. “If you don’t have the officers, the prisoners can’t move” to jobs, classes, exercise or therapy.

The staff cutbacks coincided with a proliferating prison drug business; spice (a synthetic cannabinoid), heroin and, increasingly, fentanyl are widely available in prisons, where the trade is more profitable than on the street.

Taylor says the levels of violence are “marginally better than in the dark days” of the riot-prone 2010s, but that is faint praise. The Ministry of Justice’s quarterly safety statistics in May showed rising numbers of deaths in custody in men’s prisons, sharp increases in self-harm in women’s prisons and a shocking rise in assaults in facilities housing children and young offenders.

“The danger is, a prison gets into a vicious cycle,” Taylor explains. “There aren’t enough staff, so the staff who are left feel frightened, beleaguered, overworked, which means there’s more lockup, which means prisoners get more disgruntled, which means there’s more likely to be violence, and therefore more staff will leave.”

In a system that confines people in their cells for as long as 23 hours a day, Taylor wrote in his annual overview, “there will be a price to pay for the loss of family visits, the limited chance to socialise with other prisoners, the lack of education, training or work, the curtailing of rehabilitative programmes, the cancellation of group therapy and the dearth of opportunities for release on temporary licence… In the last year, more prisoners than ever before will have left custody after spending almost their entire sentence locked in their cells.”

Taylor, who began his public service as a teacher, is especially excoriating on prisons’ failure to provide the most basic education. In his 2022 overview, he called it an “astonishing failing” that many leave prison unable to read any better than when they arrived.

“Some of the most disheartening inspections were at prisons with large proportions of young men, where the often extensive grounds and workshops remained mostly empty and just a handful of prisoners were receiving any face-to-face teaching,” he wrote. “The failure to fill the gaps in the skills and education of these prisoners and the low expectations of their abilities and potential meant they were learning to survive in prison rather than being taught how to succeed when they were released,” the report continued. “Unless these men are given the support that they need, there is the potential that they will lead long lives of criminality—creating victims, disrupting their communities and placing a huge burden on the state.”

“Of our four standards, purposeful activity has always been our lowest score, and it’s now far worse than it has been in the past,” he tells me.

Prisons are crowded in large part because of what Peter Dawson, a former director of the Prison Reform Trust, calls “sentence inflation”. People convicted of crimes are now more likely to do time, are sentenced to far longer minimum terms for violent and sexual crimes, and are kept in prison long past their minimum tariffs.

Over the past 20 years, the minimum sentence for murder—the time a person must serve in prison before release can be considered—has increased from an average of around 12 years to about 21 years.

There is abundant research refuting the notion that longer sentences lead to greater public safety. In September, the Sentencing Council for England and Wales, an independent agency that issues guidelines for judges, published a sweeping study of the scientific literature on the subject and concluded that “there is no strong evidence to support more severe sentences on the basis of their general deterrent effects. Moreover, we note that some have argued it is time to accept that sentence severity has no effect on the level of crime in society.”

But since the turn of the millennium, when politicians such as Tony Blair—and Bill Clinton and then-senator Joe Biden—recognised that tough-on-crime rhetoric can add ballast to a liberal agenda, party leaders across the board have competed to register their disdain for anything that smacks of leniency. The Criminal Justice Act from 2003, hailed by Blair as a “victim’s justice bill”, was a dramatic escalation of mandatory sentencing. It also introduced a novelty called “Imprisonment for Public Protection” (IPP), an open-ended sentence judges were required to impose when an offender was presumed to be a danger to society. The presumption was based on previous convictions for any of 153 crimes not normally carrying life sentences. An offender sentenced to IPP was essentially declared a menace until he could convince a parole board otherwise. (The IPP, which many people found confusing, including crime victims, was repealed in 2012 and replaced by fixed minimum sentences. But as of mid-2022, 2,926 people remained incarcerated under IPP.)

The race to incarcerate accelerated with the formation of the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government, Andrea Albutt, president of the Prison Governors Association, told MPs in May. “Since 2010, 11 justice secretaries (one holding the post twice) and 13 ministers (one holding the post twice) have, through political buffeting and interference, achieved nothing but decline in the function of prisons.” She warned that UK prisons are at risk of becoming “little more than warehouses of despair, danger and degradation”.

In the UK, as in the US, would-be reformers in government fear being caricatured by an increasingly populist right-wing media. “We’ve had a series of justice ministers mainly concerned with covering their own asses,” a senior prison executive tells me. “They’re more concerned with what the newspapers might say than with what works.”

One fact that my British friends all seem to know about American prisons is that some are run by private contractors, a comingling of profit and punishment that has roots in the slave plantations of the American South. My friends are surprised when I tell them that the UK does the same thing, only more so. Eight per cent of prisoners in the US reside in facilities operated by private firms. In England and Wales, the number is over 12 per cent (it is 15 per cent in Scotland). More surprisingly, most reformers I met—including those who worry about the morality of earning profits from the suffering of others—conceded that some of these privately run prisons are among the best in the UK. Because they pay better, they attract and keep the most experienced staff. Because they don’t have to clear every idea with the risk-averse Whitehall bureaucracy, they have been quicker than publicly run prisons to introduce modern technology and innovative programming.

The private operators have the important advantage of managing newer facilities. The only attempt to privatise one of the Victorian-era relics, HMP Birmingham, ended badly in 2018 when prisoners nicked an officer’s keys and ran riot for 14 hours. The prison service took back control of Birmingham from the for-profit contractor, the London-based security company G4S, and has never tried that again.

Dawson, a former governor of state-run prisons, says the public sector has much to learn from privatised prisons. “Birmingham before it was privatised was a shameful place, and it certainly improved post-privatisation,” he told me. “The riot then happened at a time when many prisons were suffering serious disorder, and there’s a reasonable argument that Birmingham was unlucky.

“The private sector has shown that it can do at least as good a job as the public sector,” he added. “Crucially, prisoners will often say that private prisons treat them better.”

Pia Sinha, a psychologist who ran both men’s and women’s prisons before succeeding Dawson at the Reform Trust in April, agreed. “When we had a pot of money within the women’s directorate and we wanted to pilot something, we would always go to the private prisons first because they are much more likely to make those pilots work.”

I spent time talking to staff and prisoners in two privately managed prisons, the 12-year-old HMP Thameside, run by the global services giant Serco on the outskirts of London, and the brand new HMP Five Wells in the Midlands, managed by G4S.

Like other privatised prisons in the UK, Thameside has been ahead of public facilities in introducing technology that makes management more efficient and life inside more bearable. Each two-man cell has a digital dashboard that can be used to stay in touch with families, schedule classes and doctors’ visits or order necessities from the commissary. A full-body scanner replaced the humiliation of cavity searches for contraband. (In a kind of high-tech arms race, some dealers now use drones to drop drugs in prison yards.) The prison is equipped for video conferences with courts and lawyers, saving the cost and tedium of escorting prisoners to the courthouse.

You have to be an absolute expert at pretending not to be afraid

No one would mistake Thameside for a holiday retreat. It reckons with high rates of mental illness, overcrowding (built for 900 prisoners, it now houses over 1,200) and a shortage of meaningful activities. The bulk of the population consists of prisoners on remand—awaiting trial or sentencing—so there is a lot of turnover, which contributes to an air of volatility. Jack Ziepe, an assistant director who shows me around, says that a few years ago he let his guard down in the segregated housing unit and a prisoner broke his nose. To work in a prison, he confides, “You have to be an absolute expert at pretending not to be afraid.”

Still, in a realm known for staff transience, Thameside has a measure of management stability. Ziepe has worked at Thameside since it opened in 2012, and told me the job made him proud—not an adjective I’ve often heard applied to prison work.

Before he was recruited in 2020 to run Thameside, David Bamford, the director (as private-sector wardens are called), was in demand as a troubleshooter; he worked at 10 public-sector prisons, five as governor, leaping from crisis to crisis, putting things in order and moving on. At Thameside he relishes a chance to stay at one prison long enough to build an experienced team and a healthy culture. And while he is accountable not only to the chief inspector of prisons but to a Serco contract full of performance metrics, he doesn’t miss the political posturing, inertia and micromanaging of the public sector.

Five Wells, which opened last year, is the UK’s showplace prison. Andrea Coomber of the Howard League—who opened prison doors for me that the Ministry of Justice would not—refers to Five Wells as “the one you show the French justice minister” as evidence of British enlightenment.

Outside, it has the utilitarian look of a new airport. Most inmates have single rooms, windows without bars, digital tablets, access to gyms and snooker tables. The toy-stocked family visit room is the cheeriest that I’ve ever seen. In an attempt to avoid stigmatising language, staffers are expected to refer to prisoners as “residents” and cells as “rooms”, a gesture that led the Daily Mail to label Five Wells as “HMP Woke”.

When I visit in mid-May, the prison holds 1,400, still ramping up to its full capacity of 1,750 inmates. The director, Will Styles, has been on the job precisely four days, and readily admits to “teething pains”. That morning the staff are caught off-guard by news that a prisoner who was due for imminent release had no resettlement plan.

We spend most of our time at Five Wells with the “super-enhanced” contingent: about 60 of the most trusted inmates who form teams of mentors to help screen new arrivals for issues including drug histories, learning disabilities and gang affiliations, to get them orientated and sign them up for programming. In turn, the “trustys” get abundant time out of their cells and a voice in how the prison is run. “If you’re going to have a prison experience,” one of the mentors tells me, “this is the place to have it.”

If you don’t hire former prisoners, you’re not a diverse employer

More than the public sector, Five Wells feels very corporate—lots of metrics and flow charts, and branding and incentive programmes and employee-of-the-month-style postings, with the super-enhanced cadre serving as a kind of middle management. I don’t mean this as a criticism. On the contrary, one of the things I find distressing about most prisons, whether in the US or UK, is the waste of human potential. I know former offenders—who are now my students and colleagues—who say that prison was where they were first offered a sense of purpose.

My question is how the private-sector model will fare when the Ministry of Justice goes on another austerity kick, when the next round of contract bidding becomes a cost-cutting derby. That’s what happened when the government set out to privatise probation.

James Timpson is CEO of a retailing service empire that offers dry cleaning, clothing alterations, key cutting, watch repairs and photo processing. He also underwrites training academies in 92 UK prisons, where inmates learn occupational skills (excluding, for obvious reasons, key-making). He employs nearly 500 formerly incarcerated men and women in his retailing workforce of 4,500.

Timpson says some employers who once would have shied away from hiring someone fresh out of prison now actively recruit prisoners nearing release—a result of a tight labour market and a desire to be seen as inclusive. “If you don’t hire former prisoners, you’re not a diverse employer,” he tells me.

But he sees a squandering of potential in the government’s unwillingness to invest more in rehabilitation and re-entry. The probation staff that supervises the resettlement of prison leavers is even more threadbare than the prison staff. A probation officer may have as many as 100 cases, Timpson says. “They just can’t keep up.”

For every person imprisoned in England and Wales, another three are on probation, free but ostensibly supervised. They too often emerge from custody alienated, with no marketable skills or stable housing, with limited access to welfare services and unprepared for the temptations of the free world. Not surprisingly, about one in four will be back in court within a year for a crime or parole violation.

The probation service has its own inspectorate. In June, it reported that more than 500 serious sexual or violent offences are committed every year by people who are under (or have recently left) probation supervision. It calculated that 42 per cent of the offences were committed by probationers who had been assessed as posing only a medium risk of serious harm.

Another investigative agency, the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, examined the deaths of recently released prisoners in the year ending last September. Of the 48 deaths examined, fully half perished from drug overdoses and 10 committed suicide. The ombudsman found that the files prisons handed over to probation officers too often lacked critical information about mental health and drug history. Many, lacking supportive family, safe housing or ready work, fall through the cracks.

“When I first started doing parole hearings, the average stay in a [government] hostel upon release was six months,” says Dean Kingham, a prison lawyer for about 15 years. “Now, because of pressures on space and lack of investment, it’s normally no more than three months.”

Back in 2014, the government’s answer to what was already a worrying trend was to reorganise and privatise, and it split probation in two. It was a fiasco.

“It was always a money-saving exercise and a belief that the private sector could do anything on the cheap,” John Podmore, the former inspector and governor, recalls. “The theory was to separate the high-risk prisoners to the national service and leave the medium- and low-risk to the private sector. Unfortunately, they created no mechanism to establish the difference.” The private sector offloaded more and more difficult cases to the national service, which staggered under the workload.

A case study last year by Raj Johal and Nick Davies for the Institute for Government thinktank found that large, for-profit providers also squeezed out small companies and local not-for-profits that could have provided useful services.

In 2019, the government announced it was bringing the management of medium- and low-risk offenders back in-house. But the reunification suffered from a rushed timetable and a clash of cultures. The few tangible benefits introduced by the private providers—mainly new information technology and case management software—were lost in the civil service bureaucracy.

The last stop on my UK prison tour was HMP Pentonville in north London. It opened in 1842, five years into Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign. Built for 520 prisoners, the facility houses more than double that number, many on remand. The day I visited, the chief inspector had just issued an interim report on Pentonville which said it was “extremely disappointing” that, despite repeated warnings, there had been “no meaningful progress” on the “critical priority” of overcrowding. On the contrary, the government plans to increase the population.

Ian Blakeman, the governor of Pentonville, says that between the churn in staff and the churn in prisoners—both largely out of his control— he spends half his time on HR paperwork.

“The more creative stuff you can do, the more you can get people into a rehabilitative mindset,” he told me. “But there’s a constant pressure on bed spaces.”

Pentonville’s proudest example of the “creative stuff” is the “neurodiversity” wing, designed for about 45 prisoners with autism, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, who struggle in the general population.

Like most specialised prison units, the wing offers incentives—especially more time out of cells—for good behaviour and participation in therapy. It features an improvised sensory room where inmates in distress can calm themselves with white noise and gentle lighting.

Specialised units have become popular in recent years. Some, called “Pipes” (psychologically informed planned environments), are overseen by the prison psychological service. Others are cobbled together informally by entrepreneurial governors, sometimes in league with prison charities. Podmore, who built an unofficial drug therapy unit at a prison called Swaleside in the late 1990s, calls these “do-it-yourself” units. His project didn’t end the drug trade and he couldn’t afford much expert therapy, but the unit “blurred the traditional boundaries and something approaching a ‘community’ developed.”

“Small groups/units work,” Podmore tells me in an email. “Staff-prisoner relationships work. Specialist inputs work and involving prisoners works.”

Such programmes are hard to sustain and scale up, as American officials have learned in creating experimental units modelled on progressive European prisons. Space is often scarce and trained therapists are expensive. Budgets get cut or diverted to other pet projects. The original champions of these ventures may burn out or move to new assignments. (Innovators also risk tabloid headlines about “woke prisons.”) And when the participants start integrating back into the general population or are released, it’s not clear how long the benefits last.

But by and large, prison staff and residents are convinced these programmes work. Fostering a sense of community and empowering inmates makes for less antisocial behaviour and allows more attention on rehabilitation. A study of Pipes published last year by researchers at Queen Mary University found “preliminary, indicative evidence” of improved “social and relational functioning”.

The chief inspector, in his interim report on Pentonville, praised the neurodiversity unit as an example of what an inventive manager can accomplish in spite of the systemic challenges. But he added that “Pentonville has had more false dawns than most prisons”.

The year HMP Pentonville received its first prisoners was, coincidentally, the same year Charles Dickens visited an American experiment in prison reform that was attracting worldwide attention. The Eastern State Penitentiary, outside Philadelphia, was a Quaker-inspired innovation that conceived of prison’s mission not solely as retribution but as “restoring our fellow creatures to virtue and happiness”. This redemption was to be accomplished by keeping offenders in nearly complete solitude, to contemplate their sins away from bad influences. Dickens was appalled, writing in American Notes that an inmate at Eastern State “is a man buried alive; to be dug out in the slow round of years; and in the meantime dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair.” Numerous studies have since confirmed Dickens’s judgement that prolonged isolation amounts to mind-maiming torture.

Most prisons in the US and UK now impose limits on solitary confinement, but the practice is still used to punish misbehaviour, isolate dangerous prisoners and protect vulnerable ones.

Eastern State Penitentiary ended its isolation practices in 1913 and the prison closed in 1970. It is now a popular tourist destination, famous for its annual Halloween haunted-house spectacle and, more recently—perhaps, as a kind of penance—for presentations on the continuing horrors of prison in America.

The last time Britain undertook a major consideration of prison conditions was in the 1990s, after a 25-day violent spree that began in April 1990 at HMP Strangeways, a Victorian prison in Manchester, and spread to several other jails. It was the worst such riot in British history.

The subsequent inquiry, led by Harry Woolf, a senior judge, laid out a blueprint for prisons that would be more secure and more humane. The recommendations included reducing the prison population, especially the number of prisoners on remand; smaller housing units with single cells; more autonomy for governors; healthier diets and improved food hygiene; a major overhaul of probation; and more education and skills training.

In summary: “The Service must seek to minimise the negative effects of imprisonment, to encourage prisoners to take some responsibility for what happens to them in prison, to match the demands of life in prison as closely to the demands of life outside as the conditions of imprisonment permit, and to prepare prisoners properly for their return into society.”

The Stangeways riot had been another echo, a British version of the infamous 1971 Attica prison uprising in New York. Like Attica, it produced a period of introspection and some short-lived improvements, before the politics of tough-on-crime brought reforms to a halt.

Some of my UK sources worry that it may take another Strangeways to awaken public attention. “If there’s no crisis,” says one, with a sigh of resignation, “they’ll just keep on doing what they’re doing.”