Liberal democracy, for so long seen as the natural political order, is under severe pressure. Around the world, there are countries where it is flailing or in outright retreat: look no further than Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, Recep Tayyip Erdoan’s Turkey or US Republicans’ ongoing refusal to concede that Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election.

What went wrong? One argument is that democracy has simply not delivered adequate living standards for enough people. The hope of high and sustained economic growth and falling inequality has not been realised. The Pew Research Center has found that the strongest predictor of dissatisfaction with democracy is unhappiness about the current state of the economy, while pessimism about economic opportunity, in particular, is strongly correlated. The financial crisis of 2008 undermined confidence in the market economy, so closely associated with liberal democracy.

Democracy depends on trust: people have to trust their fellow voters and their leaders. It requires social cohesion, which is hard to measure but has clearly been in short supply. When those responsible for the financial crisis escaped reprimand it created a sense of unfairness, compounded by a wider sense of disconnect between the public and politicians over countless other issues. The political shocks of the past few years have shown that the old order is at risk of collapse.

So if liberal democracy is on the wane (and populism on the rise), is there a role for industrial democracy—people exercising their voice in the workplace to reclaim the power that they feel they have lost? Can industrial democracy improve how businesses perform—increasing profits and the happiness of workers and customers? And if so, could this be one way to help shore up liberal democracy after all?

By industrial democracy, I mean more than staff engagement, where employees are consulted on issues related to their working conditions (now commonplace), and more than trade unionism, where worker representatives have a legal right to negotiate terms and conditions with management. I mean the democratic participation of workers in running the business—with associated voting rights and an influence over the direction of the firm. Industrial democracy introduces the sharing of responsibility and accountability between workers and managers.

The notion of industrial democracy is not new. The anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term in the 1850s to refer to workplaces where management was appointed by the workers. The socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb used it in their book of the same

title, first published in 1897. For them industrial democracy referred to trade unions—which were beginning to take off at the time—and collective bargaining.

Today, workers in some European countries are able to elect company directors. In Germany, public companies are required to have two boards—a management board and a supervisory board. In medium-sized companies, one third of the supervisory board is selected by the workers. In larger companies the proportion is one half.

A close cousin of industrial democracy is the cooperative movement. Customers and employees can sign up (sometimes for a fee) to become a member of a company that is a cooperative. In return, they can influence how the business is run and where it puts its profits, as well as receive benefits like lower prices in stores.

True industrial democracy—workers participating in how their firm is run—is extremely rare today. The John Lewis Partnership, which I chair, is the biggest industrial democracy in the UK and among the biggest in the world. It is employee-owned by its 80,000 staff, who are Partners in the enterprise. Formally, the business is held “in trust” on behalf of these Partners.

Industrial democracies have to share information in a way most businesses would not find comfortable

The Partnership operates two main brands, John Lewis and Waitrose, and is developing a new rental property arm as part of plans to diversify. It has more than 20m customers and annual sales exceeding £12bn.

There are three decision-making entities within the Partnership:

• The Chairman, who is the chief trustee or “custodian” of the Partnership, responsible for the future success of the business and ensuring it remains employee-owned. There are four other trustees—the (non-executive) deputy chairman and three Partners elected by the Partnership Council.

• The Partnership Board, which like the board of a public limited company (PLC) has a mix of non-executive directors (NEDs) and executive members. Unlike a PLC board, it also includes three Partners elected by the Partnership Council. They are not just “worker representatives”; they sit as full voting directors of the board and may work in any role in any part of the business. (The only listed company that comes close to having a similar arrangement is Capita, which in 2018 introduced workers to its board. Most public companies have worker forums or consultation groups, typically sponsored by a NED.)

• The Partnership Council, a group of around 60 Partners elected by their fellow Partners from constituencies across the country, in a set-up not dissimilar to a general election. Once elected, each councillor represents a different part of the business. Elections are held every three years; councillors can stand for re-election. If a councillor, for whatever reason, steps down mid-term, a byelection is triggered—again as in national politics.

The chairman is accountable to the Partners through the council—not to the board, there being no external shareholders. Twice a year, in a special session not dissimilar to an evidence session for a parliamentary select committee, the chairman answers to the council about the performance of the business—not just commercially but in terms of the Partnership’s broader aim to be a different type of business from other firms. There is debate and challenge, and then a confidence vote. The motion varies but typically it is centred on whether the council has confidence in the chairman and his or her plan for the business. If it does not, this can trigger a process for dismissal overseen by the trustees.

Sitting beneath the council, each part of the business has its own democratic forum. Forum representatives are elected by Partners and they table, debate and resolve particular issues, escalating major issues to the council.

Generally, the various bodies work together well. Take last year’s pay review for Partners. Pay options, within a limited envelope, were discussed in forums and at the council. The council voted to allow a change to the constitution meaning that a broader range of options could be considered. The final decision as to how much to award—and to whom—was taken by the Partnership Board.

What industrial democracy should engender—especially when combined with employee ownership—is increased trust between workers and the business. In the John Lewis Partnership, this has historically shown up in lower employee turnover, longer service and higher levels of morale compared with other retail firms. Our advantage has narrowed somewhat in the last seven years, as pay and benefits in the Partnership have come under pressure, but it remains clearly visible.

It continues to show up strongly in terms of loyalty to the business. Waitrose and John Lewis are among the most trusted brands in the UK, according to Opinium. They routinely score highly for customer service. This is a direct outcome of the partnership model, not a coincidence. I am hardly an impartial observer in drawing attention to these things, but there is a structural point worth dwelling on. Employees who own the business and have a say in how it is run are more committed to delivering high standards of customer service and better able to provide impartial advice to management.

The difference is also evident in Partners’ commitment to local communities. Eight in 10 participants in a recent staff survey agreed that the John Lewis Partnership makes a positive contribution within the communities it operates. It donates around £15m a year to charity; most goes to local schemes, with Partners actively involved.

Socrates was famously critical of democracy and argued that people need the right information if they are to exercise their vote wisely. Industrial democracy has to go hand-in-hand with an openness from management in sharing information, to a degree significantly beyond what a conventional business would find comfortable. There are a number of ways this openness shows up in practice. Information about financial performance, for example, is shared freely with Partners through a variety of channels, including internal podcasts and videos.

Another crucial underpinning is a free (in-house) press. The Partnership has operated an independent weekly newspaper, the Gazette, for almost 100 years. Today it appears in both paper and -digital form. The editor is independent of management and free to choose news of interest to Partners. Crucially, any Partner can write a letter to any manager, including the chairman, and it has to be published and responded to, providing editorial guidelines are met. A culture of healthy questioning of those in authority is strongly embedded. Transparency and freedom of speech are as crucial to a functioning industrial democracy as they are to a political democracy—and I say that as a former CEO of Ofcom, the regulator of the UK’s media.

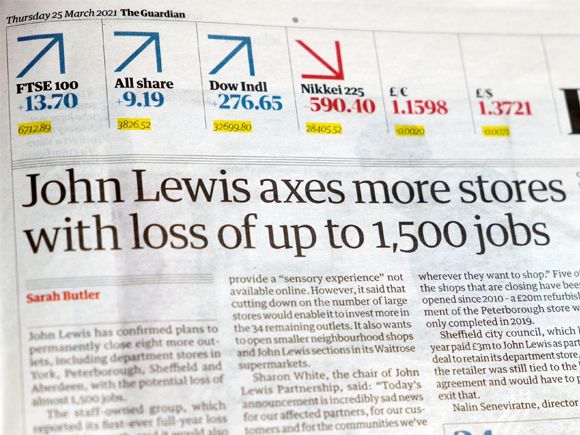

A huge test for industrial, as for political, democracy is how it holds up in tough times. When the market is growing and profits are buoyant, it is easy to have a sense of togetherness and esprit de corps. What about times when declining margins are accompanied by high inflation and fierce competition? For the Partnership, that has meant the closure of a number of John Lewis and Waitrose stores, with corresponding job losses.

Tough times bring into sharp focus the tension for Partners of being both an employee and an owner. As employees, Partners rightly want to secure as many jobs as possible, as well as to improve pay and benefits. Some Partners might even feel that membership of a trade union would serve their interests better, especially in a cost-of-living crisis. As owners, Partners want to face head-on the difficult decisions that will make the business secure. I will always remember a conversation with a Partner who had worked for many years at John Lewis in Aberdeen, who I spoke to during a visit to the store after we had decided (during the pandemic) to close the branch permanently. She, like many of the team, was understandably distressed. But she said that she could reconcile herself to the decision if it was best for the Partnership. I found that very telling.

The clear understanding that “we’re all in it together” is crucial. Nothing is more corrosive to an industrial democracy than a feeling that times are tougher for some members than others. In response to the cost-of-living crisis, we announced in September a £45m support package for Partners, with a one-off payment equal to £500 per full-time Partner, and an increase in entry-level pay by 4 per cent. We will provide free food at work for 14 weeks over winter. These steps were taken in response to the views of our Partnership Council, especially its Partner Committee.

There is a strong sense in the Partnership of what constitutes fairness, and it is centred on common solidarity. This stems from the original mission of the business to offer such a high standard of living that it would encourage workers after the war to turn their backs on communism, with the firm becoming the default model for capitalism. You could call it “socialist capitalism”. The business offered healthcare before the NHS, along with housing, subsidised holidays and leisure clubs. A sense of solidarity has coursed through the Partnership ever since.

An industrial democracy with a clear sense of purpose draws in likeminded people, motivates beyond money and chimes with customers. That is the intention behind the Partnership’s updated statement of purpose: “Working in partnership for a happier world.”

It is impossible to be unaware of the criticism of businesses for being “woke capitalists” or “virtue signallers”. I think the critique rather misses the point that employees have a choice and are voting with their feet to work for businesses that stand for something. This is especially so now that Gen Zers have entered the workforce. Equally, customers say they prefer to spend their money with companies that are active on social issues. There is also evidence that, in times of economic uncertainty, customers fall back on trusted brands. It is why I prefer the term “common sense capitalism”.

We’re keen for the Partnership to increase its impact on society. We particularly want to bring attention to the untapped potential of care leavers, drawing inspiration from schemes run by Timpson (though their initiative is different, working with ex-offenders). We have started our own employment programme, which we intend to grow in collaboration with other businesses and voluntary groups. This is the right thing to do in a partnership. It is also the commercially astute thing to do, as these young people—with the right support—will be brilliant Partners.

In the end, it’s not enough for workers to feel good about the business if customers aren’t happy and profits aren’t high enough. Evidence as to how industrial democracies perform financially compared with their peers is hard to come by as there are so few examples (which may itself be telling). The Employee Ownership Association provides some limited evidence that suggests productivity is rising faster in firms owned by employees than in other businesses.

Comparisons are complicated by the fact that industrial democracies may be barred, under their governance rules, from making maximum profit. The John Lewis Partnership is obliged under its constitution to make only “sufficient profit”—enough money to deliver on the purpose of the business as a social enterprise. Currently, the business is not making enough profit and is part way through a five-year plan to get profits back on track. In the last trading year, the firm was able to pay bonuses; this year—with the cost-of-living crisis—will be more challenging. When we do pay bonuses, they amount to the same proportion of salary whatever a Partner’s position in the company.

Even if an industrial democracy has the potential—with the right building blocks—to weather tough times like these, how does it move at pace and stay competitive?

Greater consultation and two-way communication may achieve more buy-in from workers, but at what cost? Does it slow down decision-making, and so weaken performance? And does industrial democracy encourage decisions that may be welcomed by the workers (new jobs and higher pay) that aren’t in the best interests of customers or the business?

These are clearly risks. The experience of the Partnership is that consultation does take longer, but decisions can be enacted quickly when it matters. The quadrupling of Waitrose’s online delivery slots during the pandemic is an example. The creation of Anyday, John Lewis’s new entry-level brand, in a matter of weeks is another. Operating in an industrial democracy does place different demands on leaders. They have to be able to accept constructive challenge, take in a range of views, respond to them and emerge with a clear direction without getting bogged down.

But I believe the model, as well as bringing together likeminded people, improving morale and building closer connections among workers, can generate profits that can be sustained. It could be the logical next step for companies already taking more assertive social positions and increasing consultation with workers. So could industrial democracy, relatively rare today, take off as political democracy comes under pressure? I certainly hope so.