We all know that our society is becoming more unequal; but what role does social class play in determining today’s winners and losers? I have both good and bad news for those who yearn for a classless society. The good news, according to YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect, is that most of us think that hard work and talent matter more than going to the right school or having rich parents. The bad news is that we regard today’s Britain as essentially a meritocracy for the middle classes, not yet a meritocracy for all.

Social class is a tricky subject, not least because we don’t all agree on what the labels “middle class” and “working class” mean. The conventional measurements—as recorded by the white collar “ABC1” (middle class) and blue collar “C2DE” (working class) headings in pollsters’ tables—relate to the type of job done by the head of each household. If the main breadwinner works in an office or has a professional qualification or is a senior or middle manager, then he or she is deemed middle class. Families whose breadwinner has a manual job or relies on state benefits are deemed working class.

These were pretty clear-cut classifications half a century ago, when two-thirds of jobs involved manual labour, typically in factories, mines, shipyards or on the land. These divisions are less relevant in today’s vastly different landscape, where white collars are often frayed and many blue collars have designer labels.

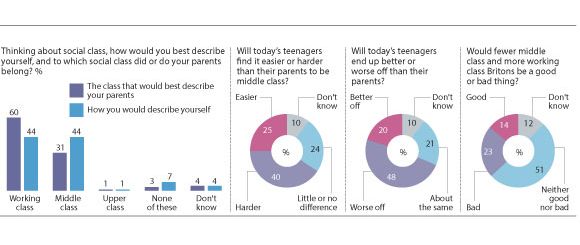

Formally, the ABC1 middle classes now outnumber the C2DE working classes by four to three. However, when we asked people to say which class they belonged to, we found a huge mismatch between people’s “objective” social class and how they defined themselves. Overall, people divide themselves evenly between working class and middle class. But fully one-third of ABC1 respondents say that they are working class—and one-third of C2DE respondents insist they are middle class.

To view a full sized version, click here

We also asked people which social class their parents belonged to. These figures confirm that the shift from a working class to middle class majority is not just the product of the traditional system of social classification; many people feel that it reflects what has happened to their own family. Altogether, 15 per cent of the public—equivalent to 7m adults—say they are middle class themselves but have working class parents.

However, we should not overstate the degree of mobility. Seven out of 10 people —more than 30m—reckon they belong to the same social class as their parents (19m working class, 13m middle class). And only 2 per cent, or around 1m adults, say they were born into middle class families but are now, themselves, members of the working class. These figures confirm that social mobility depends on congenial jobs becoming more numerous—not on the children of better-placed parents suffering the pains of outright relegation from the ranks of the middle classes if they are not up to the mark.

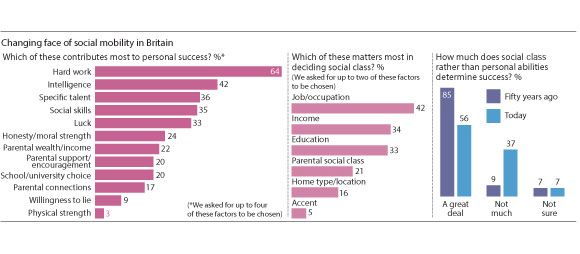

This helps to explain why most people still think social class influences life chances. Fifty-six per cent say that it affects a teenager’s prospects of doing well in adult life “a great deal” or “a fair amount.” Our perception is that it used to matter even more: 85 per cent say that teenagers 50 years ago needed the turbo-boost of better-placed parents to do well in life. But we are far from becoming a society in which people think success is purely a matter of merit, and nothing to do with the kind of family into which we were born.

This might not matter too much if we thought that the progress towards a fully meritocratic society would continue, with steadily increasing opportunities for people to enjoy the benefits of a middle-class life. In fact, we tend to think the opposite. Just 25 per cent think that today’s teenagers will find it easier than their parents to be middle class. Many more, 40 per cent, think they will find it harder. And by a margin of more than two-to-one, we fear that today’s teenagers overall will be worse off than their parents.

The gloomiest of all are those with no direct experience of working class life. Among the (subjectively) middle class children of middle class parents, pessimists outnumber optimists by more than three-to-one. Our age of austerity may be causing some retreat not only in living standards, but also in our journey towards a society in which the benefits of being middle class are open to all.

To view a full sized version, click here