At 3.12pm on 20th November 2014, Emily Thornberry hit tweet. The Labour MP for Islington South and Finsbury, then serving as Shadow Attorney General, posted a photograph of a house in Kent, decked with three flags bearing the St George’s Cross. Her caption? “Image from #Rochester.” At 6.15pm she tweeted again, apologising for “any offence caused by the three flag picture,” adding that “people should fly the England flag with pride!” By 10.30pm she had resigned from the front bench.

The political autopsy lasted days, focusing largely on the question of whether Thornberry had opened a window on to metropolitan Labour’s cultural alienation from—and perhaps even contempt for—working-class voters in small towns. But looking back, the significance of that episode is not as a snapshot of political turbulence, but as a development in the process that turns turbulence into news. What stands out is the medium, not the message. In autumn 2014, Twitter was already a recreational habit for Britain’s political class. But “Image from #Rochester” marked a watershed moment for the social media website. Without the super-accelerated online frenzy, there was no story.

Four years later, the Twitterstorm is not only routine, it is the qualifying benchmark for newsworthy controversy. Anyone who doesn’t squander hours every day on the platform might be baffled as to why its name occurs with such frequency in news bulletins. A majority of UK voters still do not have a Twitter account. Yet the site’s impact in Westminster and on the way politics works is real and exceptional, not because of how many people use it, but because of who they are—politicians, their devotees and the journalists supposed to be holding them to account.

Whether the controversy is Boris Johnson’s comments about the niqab, or Jeremy Corbyn and anti-Semitism, Twitter is the place where anger congregates and provokes more anger in a near-perpetual cycle. And those are cases where the initial offence occurred in the analogue world. There are others that exist purely for Twitter. It is a laboratory capable of synthesising scandal of its own: Labour’s Dawn Butler denouncing Jamie Oliver’s “appropriation” of Jamaican jerk rice, or Tory Remainer Simon Hart using Twitter to tell a Brexiteer colleague, Chris Green, that “nobody gives a fuck” about his resignation. The sparks ignite partisan wildfires that rage intensely for a few hours or even days. They matter because they scorch a little more of the earth, charring the space where a more balanced and civil political debate might have been possible. Twitter has made the impulse to burn a normal part of political culture.

This trend’s undisputed commander-in-chief is Donald Trump. The US president uses the platform for hiring, firing, abusing and ranting. It is conceivable that he will one day use it to declare war. For that reason alone it is an essential source for the world’s conventional media. But the extraordinary feature of Trump’s Twitter voice is how unexceptional it is for the site. It feels like a natural milieu for fanaticism—a perfect tool for populists and an incubator for aspiring despots. This polarising medium is now embedded in Westminster’s political culture—with pernicious consequences that are only just becoming clear.

#TweetDreams

A feature of most successful innovations is that their purpose is easily grasped: the railways outpaced the horse-drawn carriage; the printing press out-powered the manuscript; the mobile phone was, well, mobile. But Twitter’s purpose wasn’t obvious when it was launched in 2006. I was sceptical when a fellow journalist explained the concept and predicted that it would catch on. He was right. By 2012, the number of Brits with (more or less active) Twitter accounts had overtaken the number of people who regularly bought a newspaper. A method for mass communication that bypassed the editorial filters of conventional media held obvious appeal for politicians. Some dreamed of an egalitarian future where everyone was their own editor. Besides, here was a place to promote yourself and amass followers—an irresistible commodity to any candidate. Crucially, also, it was fun—a place of jokes, spontaneity, serendipity, discovering new voices, making unexpected connections, generosity, heart-warming tales, lost teddies reunited with their owners. And cat pictures.

#MoodNews

In parliament’s press gallery, reporters monitor Tweetdeck—a platform for viewing multiple Twitter streams in parallel—the same way the news wires are watched. But conventional wire services—Reuters, PA, Bloomberg, AP—specialise in dry, fact-driven stories crafted to an orthodox journalistic template. Twitter packages notifications of events with mood and reaction. It shows you the jokes about a story before you have grasped what has actually happened. It serves as a kind of Zeitgeist-wire, shaping the collective journalistic view of where a story is moving. Twitter has had an effect on political news akin to the impact high-frequency trading had on financial markets. Just as algorithms there can subordinate judgment to trend, intensifying the move in the market in whichever direction it already happens to be heading, so with Twitter we can see volatile intra-day trade in an individual’s political stock. The system can then be gamed by organised campaigners who tweet and retweet in a quasi-robotic frenzy, and it can be manipulated by actual robots—bogus accounts that typically amplify partisan opinions, on behalf of the Russian security services or anyone else who might wish to cause trouble. One study estimated such “bots” might constitute 9-15 per cent of all Twitter accounts. It can be hard to distinguish between a mechanical troll working to a wrecking algorithm and a human maniac sitting in pyjamas firing off outrage through the night. Part of journalists’ professional vanity is the belief that we can observe a herd while detaching ourselves from its movements. We suppose we can be on Twitter without belonging to Twitter. We see its flaws while flattering ourselves that it doesn’t prejudice our work. This is untrue. We cannot un-see the things to which we are exposed, nor insulate ourselves from peer pressures and taboos. It is no easier to look at Twitter without being influenced by it than it is possible to jump into a river without getting wet. It doesn’t matter that you claim to be swimming against the flow. You are still in the water. “The lobby”—the pool of accredited journalists with privileged access at Westminster—is a club to which Twitter is brilliantly adaptive. It is a fiercely competitive environment, but also a collegiate one; shaped by simultaneous rivalry and collaboration. Individual journalists hunt their own scoops, of course, but on quiet days there is a tendency to scavenge as a pack. Gossip and comparing of notes leads to a corporate view on what happened and why it matters. Journalists and commentators follow each other, gathering at the virtual water cooler. This exacerbates the tendency to form cartels of interpretation. Theresa May’s conference speech, for example, will be so thoroughly picked over in real time on Twitter that settled views on whether it is a success or not will be formed before the prime minister has finished speaking. Just as Westminster journalists coalesce into settled communal opinions, Twitter as a whole organises itself with amazing speed into opinion-based regiments. Different details of the driest economic data—new figures for export volumes, for example—will, within minutes, be seized on by Remainers and Leavers and brandished as proof that Brexit is having whatever impact they said it would have all along. Through the mechanism of choosing who to follow and which voices to exclude, users construct opinion silos—deep but narrow, socially homogenous echo chambers, held together by shared political assumptions. Inside these echo chambers we are all susceptible to common, powerful cognitive errors: confirmation bias—believing things because they support what we want to believe; selection bias—privileging data that supports our conclusions; availability bias—presuming that whatever is most recently seen is also most important. Users are constantly promoting content that suits their biases and either ignoring or denigrating the rest. They alight on the most extreme manifestation of a rival view and hold it up as proof of another tribe’s irredeemable wrongness. Conformity to tribal ethics is rewarded with retweets and approving replies; contrary opinion can be treated as heresy. And so everyone bids everyone else up in a currency of implacability and indignation. Twitter appears to give broadly equal value to every tweet. The blatant lie sits alongside the truth, competing in the market for attention on the same terms; and so lurid fiction gets more traction than dull fact. It was 1710 when Jonathan Swift fretted that “falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after it… if a lie be believed for only an hour it has done its work.” But when 350,000 tweets are sent every minute, a lot of lies can make a lot of progress in an hour. A recent example: Alex Salmond, former leader of the SNP, is under investigation over allegations of sexual misconduct. Among some of his supporters on Twitter, a belief has taken hold that this is part of a “deep state” plot to sabotage the cause of independence. As evidence, some cited the marriage of Leslie Evans, the senior civil servant in the Scottish government dealing with the investigation, to Jonathan Evans, former head of MI5. Except no such marriage exists. Leslie Evans is married to someone else (who happens to be a member of the SNP). But the MI5 plot idea outlived the corrections to the record. Like a rocket’s fuel boosters, they can be discarded once the conspiracy theory has successfully been put into orbit. Such hierarchy as there is on Twitter bears little relation to any scale of trustworthiness. Prolific users who earn the most kudos in retweets are privileged by the algorithm that determines what content more users get to see. But the ability to draw a crowd has never been an indication of honesty. There is a system of “verified accounts” signified with a blue tick, which is supposed to show that a person with some public profile offline really is the voice behind the account bearing their name. But the company stopped giving out any more blue ticks last year because verification was being interpreted—and abused—as a kite mark of veracity. And Twitter certainly didn’t want responsibility for that.#PartysOver

In British politics the partisan trenches are deeper and further apart but the boundaries of traditional party identity seem to be blurring. A peculiarity of Twitter is that it is a facilitator of both trends. It isn’t that long ago that digital technology—starting with the humble pager—could be used to impose message discipline on MPs. That top-down transmission now looks obsolete. Politicians who tweet the line-to-take verbatim from their party’s press office appear ridiculous. Individual MPs now feel free to say what they really mean. But often factional loyalties, rivalries and vendettas are revealed in who they retweet—or their conspicuous silences. Labour MPs share revelations about Corbyn’s back-catalogue of liaisons with extremists; Tory Remainers declare they could never campaign for a Johnson-led party. The days when such matters were dealt with in private conclave with Commons whips are long gone. In place of the old top-down message discipline, Twitter brings bottom-up policing—a kind of ideological vigilantism as swarms of loyal adherents to one position or another impose whatever the crowd has settled on as orthodoxy. That raises the prospect of parties too divided to present voters with coherent, unified programmes and leaders so beholden to doctrinaire followers that there is no scope for the kind of compromises and consensus-building that are necessary for stable government. Even if we recognise all this we can’t seem to help ourselves. For some involved in politics Twitter is the last thing they see before going to sleep and the first thing they see when they wake up. It is compulsive. There is always the next tweet, the mesmerising chain reaction of micro-controversies unfolding in real time. This is to a healthy interest in news what junk food is to a healthy appetite. We know it does us no good and yet we keep reaching into the bottomless Pringle-tube of salty, sugary snack information.#MobOfModerates

This summer I quit Twitter for a month, my longest absence since joining in 2011. I did it partly from curiosity, and partly from fear that the site was corrupting my journalistic judgment; that I was having to battle ever harder to imagine perspectives other than the one afforded by my timeline. I didn’t trust myself not to peek, so I changed my password to a randomly generated string of characters, logged off and went abroad leaving the unmemorable access code behind. I expected to feel uncomfortably remote from the action. For a few days I experienced withdrawal symptoms: mental fidgetiness reminiscent of giving up smoking. But I still had radio, print, television and websites. I became aware that the news signal I received felt cleaner. I could imagine the crackle of tweet-interference that would accompany every development in Westminster and felt no poorer without it. I could follow Brexit just as easily, but I was not seeing it through a cloud of anger and hyper-partisan bickering. I was also aware, gradually, of thinking about politics in longer sentences. Trains of thought were proceeding further down their track, when previously they would have been derailed by a tweet, and another, and another. Sustained attention is a muscle that can atrophy from lack of use. But the most telling evidence of addiction was how hard I fell off the wagon. I binged. In print, I aspire to measured, temperate analysis. Within a week back on Twitter, I was hurling snark into the void. A friend messaged me—privately—to suggest I step away from the keyboard. I needed the intervention. Otherwise mild-mannered and reasonable people turn deliriously combative on Twitter. Cycles of aggression flare up over nothing. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that Twitter can inflict mental injury on people working in politics._______________________

? Can you speak Twitter? ?

![article body image]()

_______________________

And the rage appears endemic to the platform, regardless of the issue. It is unsurprising that disciples of radical ideologies—both far-left and far-right—express themselves ferociously. But it is extraordinary to see how many self-styled centrists have adopted extremist manners. The #FBPE (“follow-back, pro-European Union”) hashtag can turn formerly sober and unassuming europhiles into virtual stone-throwing yobs. A mob with moderate slogans is still a mob. Twitter, it seems, can radicalise anyone. That is deleterious on an individual level, but profoundly corrupting of the collective political process. The website is a vast polarising machine—a centrifuge that separates politics into the most extreme iterations of any given position. When the ideal conception of politics might be rival teams, advancing competing policy prescriptions based on some common set of facts, Twitter turns us into quasi-religious cults, looking at the world in terms of righteous believers and despicable blasphemers.#HateNotHope

Hate mail has been around for as long as people have been able to write. But, again, Twitter seems structurally conducive to abuse. It is a lot quicker to find someone by their @ handle and send a message than to post a poison-pen letter. Addressing a person’s account directly contains the frisson of saying something to their face but with the cowardly advantage of being, in reality, nothing like saying something to someone’s face. The cloak of anonymity or pseudonymity leads to a well-documented “online disinhibition effect,” a behavioural distortion caused by the absence of the social signals that surround analogue communication. This can cause shy, lonely people to open up and make friends. But it can also cause people to abandon empathy, and lose impulse control. One survey of tweets in the six months before the 2017 general election campaign found that one recipient alone, Diane Abbott, was the target of nearly half of the total volume of hostility directed at women MPs. Of 140,000 tweets using Abbott’s handle—which tweeters include to help ensure she sees them—one in 20 was abusive. Abbott, as Britain’s first black female MP, is quite used to racist and misogynistic verbal attacks. Yet she told researchers that the digital tsunami is qualitatively and quantitatively new. “It’s the volume of it which makes it so debilitating, so corrosive, and so upsetting.” White men have a privileged experience of Twitter. They might get be verbally attacked, which is unpleasant. But they don’t open their accounts every day expecting to see rape threats, violent images, racial slurs and every manner of frenzied intimidation. And since there is research also showing that men in politics disproportionately follow and retweet other men, there is a self-reinforcing complacency; a tendency to reframe discussion of abuse in terms of free speech, focusing on the notional rights of the abuser, instead of engaging with the capacity of Twitter mobs to corrode free expression by silencing women and minorities. Twitter has rules against hate-speech, but it is selective and slack in policing them. When Apple, YouTube and Facebook banned the accounts of Alex Jones, a far-right American peddler of wild conspiracy theories, earlier this year, Twitter initially refused, only bowing to pressure weeks later. Arguably Trump’s promotion of racially incendiary material puts him in breach of the site’s code of conduct, but its executives are in no hurry to silence their biggest box-office client.

#LogOff

Twitter insinuated its way into our politics quickly. Could it slip out again just as fast? Fashions change. MySpace was the future once. There might be a tipping point where the unpleasantness suffocates the last remnants of what made it fun and worthwhile. It feels like the Dead Sea, getting ever saltier as its boundaries shrink. Soon maybe there will be no vibrant life in the water. In theory, there could also be an evolution towards greater civility. But Twitter, like other social media giants, doesn’t want ethical accountability for what happens on its site because accountability sounds like legal liability. It isn’t a public utility or a charity. It is a business, and a business that has, whether its executives like it or not, become unavoidably and intensely political. Civilised, multi-party politics requires an exchange of ideas, rival opinions as well as delicate—and sometimes fraught—brokering between competing interests. A structure that accelerates and promotes conflict is inimical to the conduct of democratic pluralism. It looks like a weapon of civic destruction. A subtle thread connects manners and democracy. To behave well in the town square, not flinging abuse at strangers, for example, is a habit born of mutually recognised rights and unwritten norms. Those social codes are as much part of the democratic eco-system as free elections and independent courts. The protocols of the Commons, including prohibitions against “unparliamentary language,” exist for a reason. It seems quaint that MPs can be censured for calling each other liars, drunkards, traitors, guttersnipes and suchlike, but the code reflects a recognition that political debate is a form of verbal combat and needs rules of engagement. When a political culture is bleached of civility, when the public realm becomes pathologically ill-mannered, it loses its capacity to mediate between competing interest groups. It becomes more brittle and less amenable to the ethos of compromise without which a pluralist democracy cannot thrive. This all might sound overwrought—hysterical hyperbole that is itself conditioned by the climate on what is, in fact, just one website. Maybe Twitter is no more than a distorting mirror, showing us a contorted version of ourselves—more a diversion from real politics than a dangerous disruption? It is both: superficial and sinister. It is pointless and yet somehow also profoundly important for the present political moment. When we have emerged from the present period of turbulence and flux, we shall surely look back and marvel at the role we allowed this strange website to have in our public affairs. Those of us who are glued to it today will then recall with a mix of nostalgia and shame the way we were so enthralled. We will ask ourselves what the point of it really was. And there will be no answer. Read a case study of polite politics vs Twitter twaddle_______________________

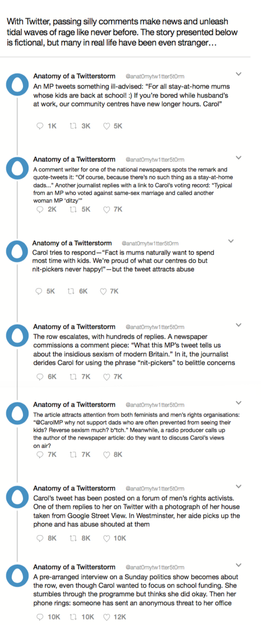

Team Prospect: how a Twitter row escalates

![article body image]()