Francis Fukuyama's book, The End of History and the Last Man, achieved world-wide celebrity because of its bold claim that with the fall of Soviet communism the institutions of democratic capitalism constituted "the final form of human government": human history-understood as the history of conflicting ideologies-had ended. Much criticised for its neglect of nationalism, religion and ethnicity as causes of conflict, Fukuyama nevertheless reaffirms his thesis in his new book, Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity.

In Trust, Fukuyama identifies the cultural sources of differences in economic performance among different types of capitalism. He finds one source of divergence in the "social capital" embodied in habits of trust. Fukuyama argues that differences in trust between cultures are reflected in varying types of economic activity. Thus Chinese societies, in which high levels of trust exist within but not between families, contain large numbers of flourishing family-based firms, whereas societies such as Japan and the US, in which trust relationships are strong among people who are not kin, are marked by the growth of large-scale business enterprises.

Fukuyama's book demands that the perception of America as a radically individualist culture be revised to allow for the strong civic culture noted by Alexis de Tocqueville. But Fukuyama warns that the growth in the US of a culture of litigation and of unconditional rights is reducing its competitiveness with the emerging Asian powers.

Trust shows him responding to post-cold war anxieties about the future of democratic capitalism. He now acknowledges the profound ramifications of cultural difference. Having achieved global fame (while an adviser at the US State Department) as an expositor of western triumphalism following the Soviet collapse, Fukuyama has re-emerged in the mid-1990s (now at the Rand Corporation) as a theorist of global economic rivalry and, perhaps, of American decline.

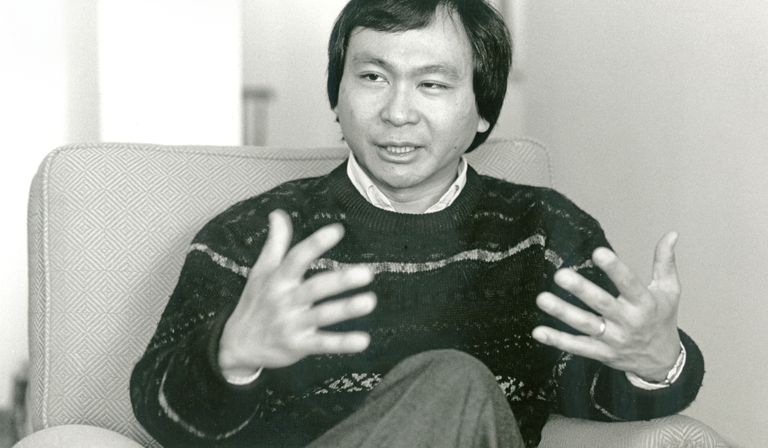

Born in Chicago, the son of a Protestant preacher, Fukuyama has a Japanese mother and paternal grandfather but cannot speak Japanese and gave up studying Japanese politics while at Harvard, finding it "too boring." He is a staunch Republican. John Gray spoke to him last month.

Q: In your new book Trust you restate your view that the world's political and economic institutions are tending towards convergence. How does your present view differ from The End of History and the Last Man?

A: I don't think I have changed my views on this. If you read The End of History carefully I actually had a section on the importance of culture. I said that liberal modernity was not self-sustaining—that a society based on rational individuals simply contracting with one another to satisfy their narrow self-interest didn't work. But it was not my main point of emphasis then. If you take seriously my view in ^ that basically there is no alternative to our existing institutions-we are all going to be living in capitalist democracies with elections and party systems-then the question of trust is what follows naturally. Differences between societies and their social problems are going to manifest themselves on a cultural level, not on the level of states and public policy. The current problems of the US ultimately exist on a cultural level. We have a big problem with family breakdown in the US and I have not heard any intelligent proposals about how it can be addressed at an institutional level. It originates in cultural changes and developments which have occurred over the past two generations. The solution must be found at that level.

Q: You note that the explanation for family breakdown in the US in terms of welfare institutions doesn't hold up, given that in many European states there are more advanced forms of welfare and less pathology in family life styles. To what extent do you see the workings of individualist capitalism in the US contributing to family breakdown?

A: I suspect this is one of the areas where you and I disagree. It is obviously the case that there is a correlation between income and family breakdown: the poorer you get the more likely you are to have a single parent family. But what I have observed is that among ethnic groups in the US the correlation varies tremendously from group to group. Poor Asians, for example, have much stronger families than poor African Americans. Furthermore, in earlier periods such as during the depression, there was some increase in family breakdown but nothing as dramatic as what you see today. The failures of 1930s capitalism were far greater than those of the 1980s and 1990s.Yet in the latter two decades the rates of family breakdown really went through the roof.

Q: American market capitalism imposes greater demands of geographical and labour mobility upon individuals and families than in any European country. Doesn't this impinge on family stability, especially when two partners are forced for economic reasons to work in different cities?

A: I am not convinced of it. I think that a cultural choice was made in favour of mobility before the market ever forced people into it. American children, when they reach college age, often go to college in a different city, even on a different coast, from where their parents live.They want to break the bond for cultural reasons. It is actually rare for the pressures of the capitalist market place to force two spouses to work in different cities. I know some people who do that by choice-they both have very high powered careers and so they simply don't want to make the concessions of living in the same city.

Q: It might be that there is a tension between the culture of mobility -whether or not promoted by American institutions-and family stability. In the UK mobility is declining despite all the labour market reforms. But it is different in the US, where mobility and individualism reinforce each other.

A: I think mobility is destructive. It is less destructive for families than for the community. Usually mobility affects families as a whole: you pull your kids out of school and you move as a unit, so the family structure is not very much affected by that. But if a company relocates you from Cincinnati to San Francisco, then your attachments to any neighbourhood disappear. That, more than anything, accounts for the fact that Americans don't know their neighbours.

Q: One thing that seems counter-intuitive in your latest book is the argument that the US, like Japan, is a high trust society. You also chart the decline of trust in the US: the growth of legalism and mass incarceration in response to crime. Are these singular to the US and what accounts for them?

A: I think that this is something which has developed within my lifetime. In the 1950s a European visitor to the US would not have found nearly the same level of public fear walking down the streets in New York City. One misperception about the US is that this lack of trust is deeply ingrained. That isn't the case. There has been a recent loss of trust and the huge surge in the level of litigation is evidence of that. Why has there been a decline of trust in the US? One reason is the capitalist market place itself. When, for example, the Japanese competition wipes out an industry it has negative effects on all sorts of things. The second reason, which I take more seriously, is the culture of rights. It is crucial in the US because it was always inherent in American liberalism that you have a Bill of Rights based on a virtually unlimited conception of the autonomy of the individual and the sanctity of man. Most of the written constitutions on the European continent balance the rights of the individual with a clause talking about the responsibilities of the individual to the larger community. This element is missing from the American Bill of Rights: there is no precedent for Good Samaritan behaviour in the constitution, no positive duty towards others. Of course, this lopsidedness was there from the start and the question is: why does the breakdown of community and family arise only in the 1960s? I think it has to do with a change in the intellectual climate, which had specific causes within the civil rights movement, which was a response to a very obvious violation of the rights of racial minorities. The success of the early civil rights movement then became the model for every disadvantaged group in society, from women to the handicapped, to native Americans. They used the courts and the Bill of Rights to achieve economic redress and equality. Another factor was the irresponsibility of the political elite itself, and the impact of political scandals such as Watergate. Vietnam, too, was destructive of political authority. The combination of all of these factors took away the respect for authority at all levels which previously restrained what was inherently a rather individualistic system. If you want to understand the breakdown of both community and family in the US, then those factors are far more important than capitalism itself. If you look at the 50-year period between 1850 and 1900 and compare it to the 45-year period between 1950 and 1995, the social changes brought about by capitalist development in the earlier period were much more severe. The US was probably 85 per cent agricultural in 1850 and shifted to being probably 60 per cent industrial by the end of the 19th century. You had huge migration of people within the country, as well as a huge immigration into the country.

Q: Surely this pattern of family breakdown, apparently so deep and irreversible, challenges a key claim in your book, which is that modernity and tradition can co-exist in equilibrium for very long periods. Haven't current global market practices speeded up the process of de-traditionalisation?

A: I don't believe that there is an inherent tension between capitalism and the maintenance of pre-modern traditions. But it may be that that equilibrium can't be sustained for ever.

Q: If, as you claim, it was a change in the climate of ideas which caused family breakdown, wouldn't it have been more profound in Europe, where socialist and leftist ideas occupied a prominent place in public culture?

A: European societies were more communally orientated from the start. The instability in the US stems from its rights-based social culture. This belongs more to the political side of liberalism than to the economic side. Capitalism itself is not a given; it can actually be profoundly shaped by pre-existing social structures. Capitalism can interact with existing moral and social structures in a way which creates new forms of community. In Japan, for example, everybody used to live in a village, you had a highly structured communal life centred around farming. Now it is all centred around the corporation and the same kind of ties and obligations exist, except that it is now done in a modern capitalist setting.

Q: In some of the best passages of the book you recognise that a flourishing market economy doesn't necessarily presuppose a western-type individualist moral culture.

A: If you give workers more responsibility and take into account the fact that they are social beings wrapped up in social networks and try to use that to positive effect, it can vastly increase efficiency in the work place. That is interesting, and reinforces the view that the capitalist market, within certain broad limits, allows considerable freedom to exploit human sociabilities for the ends of that market.

Q: You argue that authoritarian regimes such as Singapore will be replaced over time by forms of democratic capitalism. What's the mechanism which allows this to happen?

A: In 1959, Seymour Martin Lipset wrote a famous article in which he demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between the absolute level of economic development in measurable GDP per capita and the stability of democracy. Above the level of about $6,000 per capita GDP there are virtually no cases of non-democracy. So the question is: what is the correlation? In The End of History, my basic answer to that was that the structure of human needs begins to shift with economic development. When you are at subsistence level or just above, your preoccupations are exclusively with getting simple basic necessities and you are driven by economic needs only; other kinds of needs such as status and recognition are subordinated. Also, modern education reinforces that side of the personality which craves things such as status. Take South Korea. In the 1950s and 1960s peasants were drawn from the land into factories, they were mostly illiterate, disconnected from the larger world, grateful simply for a chance to work. They could more easily be led by their noses into militarism. But now in much of Asia there is a new "yuppy" class created by economic modernisation, active in the new democratic protest movements. In China, and also in Thailand, it is the university-educated, the newly-minted middle class, which is pressing for democratic change.

Q: If the regime in Singapore managed to continue in its present form for another 50 years or so, would you take that as a fundamental challenge, or an extreme anomaly?

A: I guess it would be an anomaly, perhaps made possible by Singapore being a small city state. But you would still have to give an explanation for how an exposed authoritarian regime with no feedback and no self-correcting mechanisms could perpetuate itself indefinitely and maintain the same standard of leadership and insulation from corruption as now.

Q: It might be able to do so if authoritarian regimes were able to shield people from economic risk while at the same time encouraging some form of innovation.

A: That is a very big "if": whether you can in fact have both of those things at once.

Q: Suppose you could, would it not create strong loyalty to the regime in power, particularly among people who had seen the effect of economic risk on their counterparts in democracies?

A: Yes, to the extent that those people are feeling self-confident now because they look at the US and see all the social pathologies, and say if that's what democracy means then we don't want any part of it. This is why I don't think that ultimately there is going to be a cultural convergence. If, as you say, countries such as Singapore could manage that process for a couple of generations, then their regimes would become self-legitimating in the same way as their markets already are.

Q: In European countries such as the UK, forms of economic risk which used to apply to specific categories of workers are now applying throughout the labour market. One can anticipate centre left and even extremist political tendencies arising to exploit that. Do these new trends pose a challenge to capitalist democracies?

A: In the US there is a tremendous problem with low-skilled labour. It used to be the case that if you didn't have a high school education then you could get a decently paid job in an auto factory. Those kinds of jobs are now becoming defunct and that really has to do with the advance of technology. As information technology moves forward it is simply easier to automate a low-skilled job than a high-skilled one and that is something new. Yes, everybody is going to have to deal with this new part of the equation. But the trouble is, I don't really see how a realistic public policy option for protecting people from that kind of risk is going to be effective, other than somehow giving these workers a higher level of skills. Simply protecting them through the traditional means of tariffs just delays the problem.

Q: It seems that the Japanese response of subsidising inefficient labour isn't open to the west-and it may not even be open to them for much longer.

A: It won't be open to them, but I am not sure that it is really the secret of their success. The great asset which the Japanese and the Germans have is their system of industrial training which allows them to move workers up to higher and higher skills. That is really the way for all advanced societies because there will always be Malaysia and 500 million workers in India to come on line.

Q: This approach puts the whole weight on continuous retraining and re-education. But there is no example of this working in the past in the US or the UK.

A: I don't think that's true. Look at American economic history. Average incomes actually dropped significantly at the turn of the century with the transition from an agriculture to a manufacturing society. That was also a period of accumulation of vast sums of wealth at the top. By the 1920s and 1930s income inequalities had been reduced by a combination of things, including the development of trade unions. The US then launched a very effective programme of public education, raising literacy rates and general educational levels so that the workers could be more usefully employed. I don't see what the alternative to re-education is, because even if you cut yourself off from the world of Malaysia and Brazil, they will still go ahead without you.

Q: Are there any public policy initiatives which you think are either necessary or desirable in countries such as the US or similar western countries, which can moderate the dynamism of market processes?

A: The fundamental issues are education and training. At times I feel quite pessimistic about the US. It is obvious what needs to be done in public education but we are institutionally grid-locked—we have increasingly poor-quality, large city public education systems which are totally paralysed by teachers' unions and entrenched bureaucracies. Our present political system isn't conducive to breaking that structure down.

Q: Do you believe that there is now, in Malaysia and elsewhere in the world, an effective anti-western political tendency which combines a rejection of western values with dynamic market economies? Or do you view these things as reactive, as transitional responses to modernisation?

A: I think they are more atavistic and reactive. The one tradition I take seriously is the Chinese Confucian one. I really think that there is a fundamental difference there. I would expect that if any such alternative arises it is going to come from east Asia and not out of the Islamic world. I know India less well, but I find it hard to believe that the stratifications in the caste system which Hinduism imposes can be compatible with a really dynamic modern technological society.

Q: What do you hope to concentrate on in your next book?

A: I am interested in the question of human equality and the effects of technology and globalisation on income and wealth distribution. American conservatives haven't yet confronted this question adequately. It is unfortunate that Charles Murray included a controversial 40-page chapter on race in his 900-page book, The Bell Curve. That distracted attention from the other 860 pages which raised the important issue: that in a certain sense all modern liberal states are becoming much more genuinely meritocratic. So we seem to have more genuine equality of opportunity, but that is not necessarily such a great thing because human ability could sort itself out in a highly rigid way.

Q: One can view that prospect with horror.

A: Yes. The typical conservative answer is to say that we are not concerned with equality of wealth but with equality of opportunity and the principle that the smart get their reward. I am not so sure it can work like that.

Q: The conservatives haven't acknowledged the possibility of a much more stratified meritocracy. They assume that a meritocracy would be highly mobile, but the growth of the overclass in the US suggests otherwise.

A: One of the reasons why we won't have continuing mobility is genetic-smart people marry other smart people and so we get a biological reinforcing of these tendencies. All of these issues really need to be thought through.