Seventy seven per cent of those surveyed by YouGov say smaller classes and better facilities give private schools an advantage in attaining the higher A-level grades needed for university (©

Andrew Dunn)

The ailment is clear but the cure is not. Most people in Britain think that private schools give their pupils a head start in life; in principle, we would like Britain’s top universities to cast their net wider in order to find more of the most talented state school pupils; but many people fear the consequences of positive discrimination.

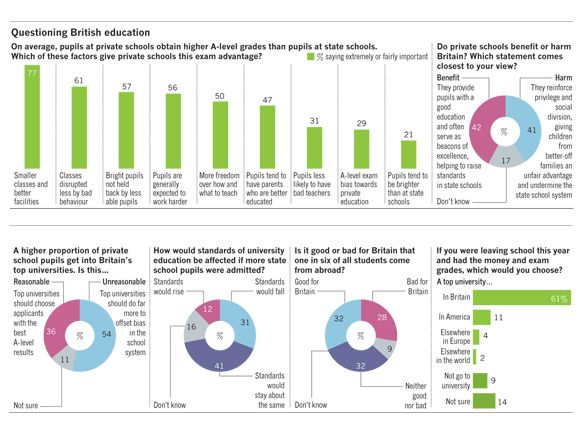

YouGov’s latest survey for Prospect started by testing nine reasons that different people suggest for the advantage, in terms of A-level grades, offered by private schools. It is this advantage that drives the bias in university admissions, with a much higher proportion of students from independent schools being admitted than from state schools. We asked whether people regarded each factor as extremely important, fairly important, not important, or simply not true.

Only one of our statements was widely regarded as untrue. Fifty per cent think private school pupils are not “generally brighter than pupils at state schools.” Fewer, 21 per cent, think it is an important factor. Britons think that by far the biggest advantage conferred by private schools is that they “tend to have smaller classes and better facilities than state schools.” Fully 77 per cent regard this as a major factor. Three other factors are seen as important by more than half of all adults: disruptive pupils in state schools (61 per cent); bright state school pupils being held back by those who are less bright (57 per cent); and a greater insistence on hard work at private schools (56 per cent).

Other factors are seen as less important. Perhaps significantly, fewer than one person in three blames poor teaching in state schools (31 per cent) or the notion that “ A-level exams are inherently biased in favour of the education provided by private schools—a fairer test of pupils’ potential might reduce the gap in exam grades between private and state schools” (29 per cent).

These results suggest that private school resources matter, but that we blame failings in many state schools (or our perceptions of those failings) for at least a part of the difference in A-level grades. Perhaps these views explain why voters divide evenly over the broad question of whether private schools on balance benefit Britain, because they are beacons of excellence that help to raise standards, or harm Britain because they reinforce privilege and social divisions. Forty-two per cent say benefit, while 41 per cent say harm—in effect a dead heat. This happens to be one of the rare issues on which Labour and Conservative voters differ hugely. Usually, the attitudes of Tory and Labour voters overlap more than tribalists on both sides might think. This is a rare exception. By 72-16 per cent Tory voters think private schools do more good than harm; by 65-22 per cent, Labour voters disagree.

As for the admissions system of top universities, voters divide three-to-two in favour of casting the net wider, to admit more of the most talented state school pupils, rather than relying solely on A-level results. But only 12 per cent think that positive discrimination would raise university standards. The desire for a fairer system is not yet matched by agreement on how to combine fairness with excellence.

We also asked about the impact of the 400,000 foreign students currently studying in Britain. The public splits three ways, with broadly equal numbers saying they are good for this country, bad, or neither. Finally, one person in six says they would study abroad, rather than at a top British university, if they were leaving school this summer and had both the grades and the money. Among under 25s, for every 100 who would choose a top British university, 46 would prefer to go abroad—33 of them to America. Recent increases in the number of British students crossing the Atlantic may reflect the beginnings of a major 21st-century trend.