In one of the election leaflets put out by the likely next Mayor of London, we learn that Sadiq Khan is the “bus driver’s son who grew up on a council estate and saved up to buy his own house.” Much of the reason why the Labour candidate has an eight-point lead at the time of writing can be found in that short sentence, a little masterpiece of copywriting. Humble beginnings as the descendant of migrants, not ashamed to have lived on a council estate, but aspirational enough to save up and buy his way into the property-owning democracy. Even the bus is a perfect touch, the big red buses that every visitor to the British capital notices immediately.

Zac Goldsmith’s pitch, on the other hand, has been total continuity with the outgoing Boris Johnson administration, which has, as the Conservative hopeful infelicitously puts it, “put London on the map.” Elsewhere, the candidates converge. There should be much more housing, and it should be “affordable,” and it should be funded through the immense wealth that sloshes through the city, there should be better public transport, and there should be a public-private Garden Bridge crossing from Temple to the South Bank. The only dissonant notes, aside from Goldsmith’s increasingly personal, dog-whistle attacks on Khan, are in their backgrounds—the financier’s son versus the lad from the Henry Prince Estate.

This consensus was christened “Londonism” by the Economist a few years ago, drawing attention to the unexpected continuity between the Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson mayoralties, with their embrace of trickle-down economics, high-density development, expanded public transport and grand, spectacular projects. Londonism would have made a good alternative title for Rowan Moore’s Slow Burn City: London in the Twenty-First Century (Picador, £20).

An eloquent, sweeping history-cum-polemic from a veteran, liberal, but increasingly prickly architectural critic, it begins with Regent’s Park, or more specifically, London Zoo. Here can be found concrete and nature, spectacle and science, public and private, planning and chaos, radical architecture like the Mappin Terraces and the Penguin Pool (both now cleared of their original inhabitants) and a new and grating form of “edutainment” and infantilism. In the part of the Zoo christened BUGS, children are forced to view the real wonders of nature through “a storm of infographic gunk... no space to think or imagine, no time for quiet wonder.”

This works as a useful cipher for the “Offer” (to use a very Boris term) that has been created in the Boris Johnson tenure. “His favourite projects,” the ArcelorMittal Orbit, a barely used observation tower devised in the toilets of Davos, the Emirates Air Line, a cable car between North Charlton and Canning Town, the Thomas Heatherwick-designed “Boris Buses,” with their mean proportions, retro-futurist design, overheating and clumsy nostalgia, and the same designer’s proposed Garden Bridge, “tended to share characteristics—the promise of private funding, brand prominence and other benefits for the sponsor, metaphorical rather than actual usefulness, the slow revelation that the work would cost the public purse more than first suggested, a spectacular quality, a preference for being on or over water.”

The Bridge is the worst of them for its insulting placing in one of London’s most finely wrought public spaces, between Somerset House’s neoclassical refinement and the complex landscape of the National Theatre, which will be effaced by a privately-patrolled bridge with golden copper-nickel cladding, mushroom-shaped columns, serrated railings and oaks on top.

The central argument of Slow Burn City is that something has gone horribly wrong in the balance that London has sustained over the centuries between public projects and private commerce. Popular histories like those of Peter Ackroyd and Simon Jenkins often describe London as a pure product of unfettered capitalism, rather than as a capitalist city sustained by massive public investment in sewers, municipal housing, public transport and town planning, where “public authorities, sometimes under pressure from popular campaigns, devised new methods to address new problems.”

Moore finds this interplay in unexpected places—even in Canary Wharf, which would seem to be both a product of unregulated development, where a “Non-Plan” gave tax breaks to businesses and developers to lure them to the desolate dockside, eventually fulfilled when it became, to use Peter Gowan’s phrase, “Wall Street’s Guantánamo” at the turn of the 21st century. Even here, however, the bankers’ towers sit on quays dredged and land decontaminated by government action, and linked by a publicly funded tube and light railway. The skyscrapers are aligned by a beaux-arts plan, established in the late 1980s and followed more or less closely since. The presence of the state, and of planning, can be found in the most unlikely places. However, Moore argues ultimately that Canary Wharf and the values it represents have tipped the balance too far towards private interests.

There’s a sense of eternal recurrence to all this. London’s first major planner was the Prince Regent and his “corrupt architect,” John Nash, the creators of the picturesque neoclassical plan that stretches from Trafalgar Square, along the Mall up through Regent Street through Portland Place to Regent’s Park, with its formal circuses and terraces and its hidden fantasy villages. In the first decades of the 19th century, this would have “looked similar to large modern developments like Canary Wharf in the way it combined limited public intentions, the taming of unruly neighbourhoods (it circumvented and walled off Soho from strollers and carriages), and property speculation based on pushing up values.” It feels “public” now because William IV opened the park up to non-aristos, whereas the contemporary squares and streets were gradually taken on by the London County Council as genuinely public spaces, a process that is now being reversed.

"'Affordability' has been the professed aim, never achieved, of all London administrations since 2000"Another similar story—beginning this time with public enterprise rather than the boondoggles of corrupt royals and opportunistic developers—is the creation of London’s sewer system, which ushered in the embryonic first all-London local government, the Metropolitan Board of Works. The sewers got built, Moore points out, not because of social concern, but because Parliamentarians couldn’t stand the stink of the Thames anymore. Setting up the unprecedented Metropolitan Board meant redressing the fact that, as the Times put it in 1855, “there is no such place as London at all’’ in legal or administrative terms, a state to which London was returned from 1986 to 2000, with the abolition of the Greater London Council.

It was controversial at the time. The Economist, for instance, opposed the provision of clean tap water because “suffering and evil are nature’s admonitions,” and “the impatient attempts of benevolence to banish them from the world by legislation have always been more productive of evil than good,” a claim that is made as insistently in 2016 as it was in 1848. Under the engineer Joseph Bazalgette, the Board of Works created great, enduring public embankments, cheerful bridges and grim streets and housing. On the whole it established a good public infrastructure for developers to fill in and reap the benefits from, shared this time with the general public. So the question is, could a Mayor of London be a Bazalgette or a Nash, someone who reconciles—even unintentionally—the demands of public and private, shared space and privacy, capital and collective?

The current Greater London Authority (GLA) has far fewer powers than the Metropolitan Board of Works’s successor, the London County Council, which controlled schools and colleges, housing, roads and bridges, public buildings, fire stations, trams and much else. The GLA and the Mayor only have real, decisive powers over four things—policing, on which there seems to be general agreement despite the many criticisms the Met has faced for a violent, overbearing approach to protest since 2010; public transport, which has expanded massively since 2000 and is likely to continue to do so; housing; and planning. Transport, not long ago considered an intractable problem, is too expensive, but much better than it was (and insultingly better than any other British city), with buses, tubes, trains and bicycle routes all smoother, better and cleaner than they were before the first Mayor was elected. The two real disasters—acknowledged, however inadequately, by both mayoral candidates—have been housing and planning.

London’s building stock, in Moore’s account, offsets the results of private development (including both the classical terraces of Zone 2 and the rangy mock-Tudor semis of Zone 5, hugely criticised in their day and now uncontroversial) with the socialised results of the state-driven, publicly-owned council housing programmes of the 20th century, from the cottage estates of Well Hall or Becontree to the modernist experiments of Spa Green and Central Hill. All of these provided that elusive thing, “affordability,” something which has been the professed aim, never achieved, of all the London administrations since 2000. Their lack of success is not surprising, given the far from “slow” burn of the financial services industry here since the 1980s, and the effective prohibition of mass council housing.

The response has been a series of percentage deals and bargains, pioneered by Ken Livingstone, elected mayor overwhelmingly as a left-wing protest candidate in 2000. Moore recalls encountering Livingstone running late and refreshed from the his jacuzzi at MIPIM, the annual property fair in the south of France where developers and councils strike many of their deals. “He was in Cannes so that he could pursue an essential part of his plan, which was to bet everything on London continuing its rise as a financial centre, with associated property development, so that he could then take a tithe of the proceeds to pay for such things as affordable housing.” Both Sadiq Khan and Zac Goldsmith (and even outlying candidates such as George Galloway) plan to continue this approach, which is interesting given that even a critic as even-handed as Moore indicts it as a total failure.

This is partly due to adjustments since Livingstone’s tenure—“80 per cent of market rent” has been the unlikely definition of “affordable”; while “David Cameron’s government gave special authority to commercial viability assessments... procedures which allowed property companies to argue that their projects would be made unviable if local authorities asked too much of them in terms of affordable housing or other public benefits, or limited their height and bulk, ‘viability’ being defined as a profit of 20 or 25 per cent.” Khan, at any rate, plans to redefine these percentage deals in a way more favourable to homes for “social rent,” but otherwise, in his campaign, “council housing” is something that features only in his aspirational biography.

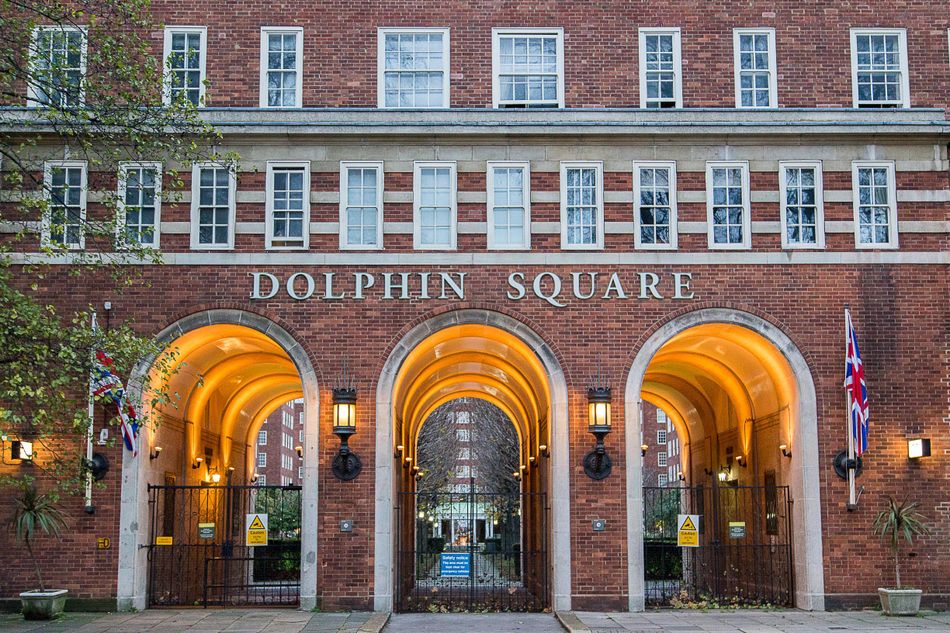

Moore makes a better case. A chapter of Slow Burn City is devoted to some of the city’s finest estates, some of them listed and inviolate, some not, and many in now astoundingly expensive areas. There’s the warm brick courtyards and nooks of the listed Lillington Gardens, “low-income housing, homes for the elderly, thoughtful architecture, peaceful enclaves, achieved in the heart of London, within earshot of Big Ben.” There’s the currently threatened housing estates of Lambeth Council, such as Central Hill, Leigham Court Road and Cressingham Gardens. There’s the monumental mid-century slabs of Churchill Gardens, where, he reminds us, residents of the nearby luxury riverside development at Dolphin Square complained about how much better the council tenants’ homes were. If it were possible then, why not now?

"The ludicrous inflation in the cost of London housing is a crisis everyone acknowledges"One reason is a process of demonisation which has culminated in “Estate Regeneration,” seen at its worst in the scandal of the Heygate Estate, built, cleared and destroyed by Southwark Council. He finds Fred Manson, a seemingly exemplary “Londonism” planner, partly responsible for bringing the Tate to Southwark, complaining of a borough dominated by council housing: “social housing generates people on low incomes coming in and that generates poor school performances, so middle-class people stay away.” So “we’re trying to change people from a benefit-dependency culture to an enterprise culture.” He later finds the same Manson working for the designer Thomas Heatherwick. The Heygate was, in Moore’s account, barely noticed by the planners, councillors and developers, who passed by its street-facing slabs without realising that just behind them was an area with satisfied residents, one of the lowest crime rates in the borough, and a carefully planned urban-rural landscape of the same school as Regent’s Park: “450 mature trees mostly put there by (Tim) Tinker and his colleagues—planes, a huge silver maple, hydrangeas, bay trees and a three-storey high loquat.”

A typical replacement is the residential tower known as “Strata,” where the experience is of being “in the fuselage of a plane that will never reach its destination, an experience that costs £625,000,” its black-and-white pipe crowned with tacked on and never-used wind turbines, mocking the huge ecological wastage of the whole project. “The council,” he concludes, “has been played by developers. It has had its tummy tickled, arm twisted and arse kicked. It has got a poor deal in return for its considerable assets, multiple promises have been broken and violence done to the lives of many who lived there.”

This is a large, obvious example, but the process by which council housing is destroyed is often subtler: “a home belonging to a council might be bought by its tenant, who might then sell it to an investor, who would charge market rents. The council, obliged to find homes for its homeless, would then have to place some of them in such a flat, paying several times the original rent for the use of a flat it had once owned.” In housing, the state—locally and nationally—has been very active indeed, but in exacerbating the problem, to the detriment of tenants, but to the impressive enrichment of landlords and developers.

However, one recent policy of the second London Mayor stands out, a legacy quite unlike the “Boris Baubles” of the bus, the Orbit, the Air Line and the Garden Bridge. The Mayor’s London Housing Design Guide has had effects that journalists and campaigners have been slow to notice, preferring to fulminate against the “Dubai on Thames” towers that even Johnson has warned about, somewhat post-factum. But every Londoner has surely noticed the clear, regular, cubic, and invariably stock-brick clad blocks of flats that have sprouted on ex-industrial “brownfield” sites (a definition that now includes municipal housing, with its “dependent” tenants and its lucrative open spaces). These contrast sharply with the “digital jism”and “infographic gunk” that has spread itself all over London in the last 16 years.

The relation between “good design” and what already exists in much of inner London could be exemplified by, say, the “Stratford Shoal,” in my view the worst single thing to have been built in 21st-century London. It is an artwork of abstract dayglo fish, specifically designed to screen post-war buildings from shoppers at Westfield. But now, there is a lot of new housing of depth, spaciousness and elegance. It is obviously “in keeping” with both early 19th-century terraces and 1950s municipal housing (though occasionally replacing the latter). For this achievement, about which the Mayor and his budding successors have been strangely reticent, Moore has nothing but praise. It “demonstrates that it is still possible for public authorities to direct city-building for the better.”

Alternatively, it could illustrate that planning is now limited mainly to aesthetics. It could be quite possible, as the new speculative housing in King’s Cross, the Royal Docks and Lewisham makes clear, for London to look as ordered and elegant as contemporary Hamburg or Amsterdam and still be just as viciously unequal—a prospect for which even the most sophisticated architectural criticism is ill-prepared. What if planning and architectural control turns out not to be in the public interest, beyond making things look nicer, just as Nash’s London meant nothing but bother and displacement to residents of Soho? Alternatively, what use to us is the (likely) possibility that in, say, 100 years, when the rents have fallen and the pressure on the city lessened, “King’s Cross Central” will be a lovely place?

Moore subscribes to the view that London’s expansion is good and necessary. It will surely hit 10m people in the lifetime of most readers. Currently, the main plan, if one exists, for what will take up the slack, is the transferring of much council housing into the private sector, whether through changes of tenure, the bedroom tax, or the legal transfer of municipal estates into the stock of buildable Brownfield. Moore has some more humane suggestions, from building up boulevards on the wan arterial roads of Zones 4-6, building on top of inner London terraces, building on carefully selected parts of the Green Belt, building more New Towns. But he knows what the real new typologies of London are. Aside from the handsome new brick flats and the depopulated districts in Zone 1 kept as oligarch holiday colonies, extending several storeys below the ground, there are the beds in sheds and “hidden favelas” or the “Zone Z homes,” where London council tenants have been rehoused in Luton, Hastings, Stoke.

The ludicrous inflation in the cost of London housing is a crisis that everyone acknowledges to the point where it becomes the topic of most conversations. There is a huge amount of evidence presented in Moore’s book that London has solved worse crises, in eras where it had less money and fewer resources. The lack of any political will to do much about it tells its own story. Central government has been actively hostile to London’s local government for decades, curiously given that it is based here, uses its services and, as Moore points out, buys flats in its better housing estates.

Both mayors elected so far, and the two major candidates this time, have offered the same solution, differing only in degree—a relentless offsetting, whereby the proceeds of runaway property speculation are proposed to be redistributed, usually by a legal requirement that developers build a percentage of “affordable” housing on or off the site, or pay for a bus stop, or fund some nice pavements and benches.

All of this relies on trying to inveigle the private sector into behaving more nicely. In a city where for nearly a century public bodies once directly built and directly owned thousands of high-quality homes and let them to people on low incomes at low rent, this is a staggering failure of imagination.

"The heroes of Rowan Moore's London are a rum lot, from sewer engineers to Communist architects"So perhaps the first place to start would be to break the skewed balance between the (actually deeply intertwined) worlds of “planning” and “development” and abandon the increasingly absurd idea that social projects can be wheedled out of reluctant corporations. Why not have councils—and the GLA—building directly? Why not expect them to want to keep hold of the land they’ve already got—or acquire more of it, even? The state, in the form of various quangos, has spent plenty of money on new private “communities” like the Olympic Village, after all. Why not build on and expand the ideas of the capital’s legacy of public projects, from the great housing estates of the 1950s to the self-build colonies of the 1980s, rather than build on top of their open spaces?

The heroes of Rowan Moore’s London are a rum lot, from sewer engineers to corrupt Regency intimates to Communist architects, but among them are Focus E15, the housing campaigners who have squatted in empty, liveable council houses in the shadow of the Orbit and the Shoal. Similar campaigns have emerged elsewhere, both in the housing estates that Moore celebrates, such as Cressingham Gardens and Central Hill, and in much more mundane estates like the Aylesbury, West Hendon or West Ken & Gibbs Green. They’re defending the housing built by London’s local governments, frequently against the opposition of actually existing local government. Their aims have been summed up by Focus E15’s wonderfully simple slogan—especially compared with London’s relentless branding cant—“These homes need people, these people need homes.”