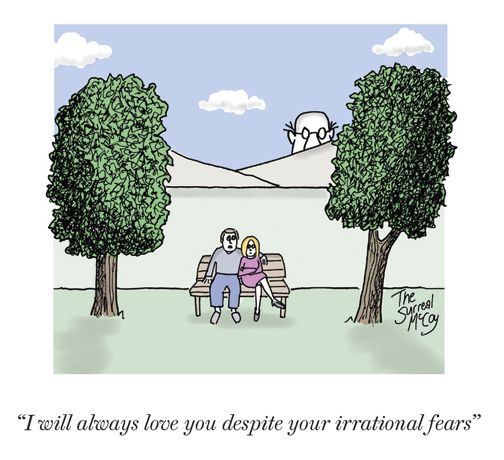

Iain Duncan Smith visits the East End of Glasgow in 2002, the scene of his "epiphany" ©Robert Perry/TSPL/Camera Press

Fifteen minutes by car up the M8 motorway out of Glasgow you arrive at the site of the epiphany. On the Easterhouse estate in 2002, close to tears at the squalor he witnessed, the Conservative Party leader Iain Duncan Smith changed his mind about politics. Posing in front of the dilapidated housing blocks, he was both incredulous and ashamed that people should live in such circumstances in a rich nation. Duncan Smith committed his party to compassion on the spot.

Though nobody can doubt the sincerity of the conversion—Duncan Smith has devoted too much time and effort to the cause—it is hard to avoid a churlish note of irritation. Duncan Smith was long in the tooth when he realised a truth the rest of us grew up with. Besides, the ambition was a little hard on the Conservative Party too, which can claim many dedicated and successful social reformers, William Wilberforce and the Earl of Shaftesbury chief among their number.

Still, better a late convert. When Duncan Smith returned to London, he established the Centre for Social Justice and turned himself into John Profumo without the scandal. Though there was always a suspicion that the think tank’s conclusions had a habit of reflecting what Duncan Smith already thought—marriage and happy families were the road to social justice—his new-found passion lasted all the way up to the point that his party returned to government and he was granted the opportunity to embody his principles, as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.

Now that Duncan Smith’s resignation from government on 18th March has closed the story, or at least this episode of it, we can assess what became of the epiphany. Did the world move? There are, of course, reasonable doubts to be entertained about the sincerity of Duncan Smith’s resignation. He walked ostensibly over a series of cuts to disability benefits which he had himself sanctioned and which were, in any case, about to be withdrawn. The Prime Minister had tried and failed to move Duncan Smith at his last reshuffle and there was a certain amount of loose talk from people in the know that a new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions was likely after the EU referendum in any case. It is therefore possible that Duncan Smith decided to leap before the push.

Whatever the truth about the resignation, Duncan Smith left office with a grave rebuke for his own government, which he accused of caring too much about austerity and too little about its victims among the poor. Now that he has been converted to the Labour Party’s argument of this six years past, one is apt to wonder where Duncan Smith has been during that time. Only we know where he has been so, as he leaves the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in a mist of compassionate anger, it is time to take an audit.

What we find is a curiosity. A former leader of the Conservative Party who turns out to be the prisoner of impractical theories. A man bound, like no conservative should be, to assumptions of social justice. A well-intentioned and committed man who inadvertently, through achieving so little, offers evidence for Friedrich Hayek’s dismissal of the idea of social justice as nothing more than a mirage.

The most surprising apostasy in Duncan Smith’s resignation was over the welfare cap. This was the law passed in the Welfare Reform Act in 2012 to impose a limit on the cash amount that any single family could take in benefits from the state. The cap limited household income from welfare to a value, at April 2017 prices, of £23,000 per annum in London and £20,000 in the rest of the country. Duncan Smith has now described this cap as “arbitrary.” So it is too, but then the very idea of a limit is arbitrary in a sense, although that does not make it also objectionable. It is peculiar that a workless household should receive an income from the state in excess of average income. The question is not whether the cap is in the abstract arbitrary but whether, set where it is, the cap has saved any money and whether it has done so only by generating genuine hardship. The answer to both questions is limited by how few families were actually subject to the cap.

The welfare cap, for that reason, was never serious welfare policy. It was conceived as a political signal of the necessary platitude that the government preferred work to welfare. The welfare cap therefore raises by implication a major question that Duncan Smith during his tenure as Secretary of State has, like all his recent predecessors, ignored—the principle of contribution.

The welfare state of David Lloyd George’s People’s Budget of 1909, was originally conceived, before it became a state retrieval service, as a pooled insurance scheme. Neither was it William Beveridge who disdained the connection between drawing out and putting in. In the preface to his famous report Social Insurance and Allied Services, Beveridge wrote that “benefit in return for contributions rather than free allowances from the State, is what the people of Britain desire.” Indeed Beveridge’s lesser known follow-up document, published in 1948, was called Voluntary Action.

Contribution was once the master idea of the welfare state. In 1964, 73 per cent of the social security budget came from National Insurance. Now it is just 40 per cent. Of the full panoply of benefits paid, just 4 per cent has a direct link with a specific contribution. The insurance idea of welfare gave way to competing ideas of need and equal income. The instrument of need (which is an irony given the hatred of the Left for the Public Assistance Committee during the 1930s) is the means test or targeting as it has, in more neutral tones, been renamed. In the 13 years of Labour government after 1997, means testing rose from 13.7m people to 22.4m. Duncan Smith, in his private moments, probably does believe, along with John Stuart Mill, that “assistance should be a tonic, not a sedative.” If he does, there is no sign of it. No single Secretary of State can be expected to recover a principle which has been a century in the dismantling, but small steps would have been feasible. Duncan Smith, though, has made no effort to offer a premium for contribution in any of his changes. Indeed the largest of his welfare savings came from a further erosion to the residually contributory element of unemployment benefit and the means-testing of child benefit.

It is surprising that Duncan Smith has not been interested in the principle of contribution. It is, after all, the best way to assuage the fear that, indefensibly, he voiced about “benefit tourism.” At various moments in his tenure, Duncan Smith suggested that migrants were coming to Britain attracted by the high rate of benefits, as if anyone settled in Gdansk would leave their family for the sheer joy of claiming housing benefit. There is no reliable evidence at all that there is a problem. Just 1 per cent of Poles who live in Britain claim unemployment benefit. Migrants as a group pay 30 per cent more in tax than the value of the services they use. Duncan Smith was unable to shake off his prejudices, and he was not even led to the obvious conclusion, that if benefits are linked to contribution, then “tourism” is impossible. Immigration remains the question that the British are most anxious about, a question that could haunt the European Union referendum, perhaps to Duncan Smith’s advantage. There are two solutions—to ban benefits for immigrants by state fiat or to make entitlements dependent on prior contribution.

Perhaps it is wrong to be too critical of what Duncan Smith did not do that he never intended to do when there is so much that he did not do that he did intend to do. Over six years as Secretary of State, Duncan Smith staked his reputation on one leviathan of a reform—the introduction of Universal Credit (UC). The UC is a simple and attractive idea. It is supposed to wrap together six of the seven existing means-tested benefits covering unemployment, housing and children. If it works it saves a great deal in administrative cost and improves incentives to work. The welfare state has become a Gothic folly with new wings stuck on old monuments. The UC makes perfect sense, in theory. If the government can pull it off, it will count as a legacy to be proud of. Senior civil servants were optimistic that it could be pulled off and many remain so. Yet that very attractiveness is a tip-off to the problem. Successive Labour ministers looked at the same reform and concluded, with conservative wisdom, that it could not be done. Sophisticated computer systems in different computer languages had to learn how to speak to one another to update volatile information on the earnings, taxes and benefits of millions of people.

You do not have to be a cynic about the government’s record with IT projects to think this is a stretch. But in fact it is perfectly reasonable to be a cynic given the record government does have with IT. It was not long after he started the process of implementing UC that Duncan Smith was told by the ministerial oversight group, led by the cabinet office minister Francis Maude, that his original design should be scrapped. Duncan Smith refused and instead ordered twin computer systems. The DWP has already been upbraided for writing off £40m in failed IT software and £91m in other assets. The projected cost so far is £500m.

Delay has followed delay and a system which was due to be national by 2017 is as yet barely even local. The early trials were beset by late payments and constant under-payments. By Duncan Smith’s original timetable, one million people should by now be receiving UC. The actual number is disputed, but even Duncan Smith’s notoriously and needlessly aggressive lieutenants can’t put it much above 200,000. Most of those who were put on to UC in the early batches are single men without dependents whose circumstances are the easiest to track. Completion has been put back, vaguely, to 2020 but it is hard to find anyone affected who believes the date.

Even if it does ever emerge the UC will be a shadow of the giant once envisaged. The gradual battle with George Osborne, the Chancellor, over funding has drawn its teeth. The UC no longer heralds a solution to the intractable problem of welfare policy—how to make work pay. The trap in a means-tested benefit system has always been that, when people go into work, the extra money they earn is offset by the withdrawal of benefits, to which they are no longer entitled. The effect is to work hard for no real increase in income. The gradient of this withdrawal is the most important element in any reform. Of course, the more gentle the gradient (the slower that benefits are withdrawn) the more expensive the change.

This sets an austere Chancellor and a reforming Secretary of State on a collision course. Since they came into government in 2010, Osborne and Duncan Smith have, to put the point mildly, not exactly got on. The Chancellor has sought cuts and the Secretary of State has resisted, believing it his duty to implement an expensive but (in his rather prim, monastic view) necessary reform. There is more than an echo here of the battle in 1997 between another expensive welfare reformer, Frank Field, and another dominant and still-prudent chancellor, Gordon Brown. The outcome is the same too. There is an iron law in these disputes which is that, when the bill comes in, the Chancellor wins. The consequence for UC is that the taper rate which has survived their negotiation is so steep that it is little improvement on the status quo. Duncan Smith cannot be blamed for losing this battle; his reform has been a victim of the government’s excessive commitment to austerity, something Duncan Smith himself has now belatedly understood.

It is hard to be definitive about the UC, in the absence of a fully-fledged scheme. Whether it does inculcate a renewed sense of responsibility or improves work incentives in any meaningful way is, after six years of trying, a question that cannot yet be answered. The observer is left with the suspicion that if UC is such a good idea, and everyone agrees that it is, yet it has never been enacted, then there might be a good reason for that, which is that it is beyond enacting. Duncan Smith’s successor, Stephen Crabb, has committed the government to ploughing on. The problem, if not the legacy, is now his. Everyone interested will wish Crabb luck and if he succeeds the judgement on Duncan Smith will change.

The bedroom tax, however, is already on Duncan Smith’s record. Though he would insist its correct name is the spare room subsidy, the battle for nomenclature has been lost. Once again, it is clear what, in theory, Duncan Smith was thinking and just as clear that it was never going to work. It sounds reasonable to argue that anyone renting a private home would purchase as many bedrooms as they needed and no more. So why should the same stricture not apply in public housing? A better match between housing demand and housing supply would be efficient and a saving to the exchequer. It all makes perfect sense in the dreamt-up world of the tidy bureaucrat.

Only the recalcitrant world isn’t like that. Duncan Smith thought tenants would move at his say-so but the public housing stock made a mockery of his command. With characteristic stubbornness, and in defiance of expert advice, he proceeded anyway. Only 5 per cent of tenants have moved and two-thirds of people who do have, according to the government rubric, a “spare” room, are now in arrears on their rent. This was a predictable, indeed a predicted, outcome to an impractical idea that should never have gone further than the drawing board. Rather than embark on a serious reform of housing benefit, which costs £25bn a year, a tenth of the welfare budget, Duncan Smith stuck to the theory in his script and sent people either into needless debt or into expensive bed and breakfast accommodation.

His record is, unfortunately, not much better elsewhere. Duncan Smith regularly claims that Britain’s fine record of job creation since 2010 is attributable to his welfare reforms but no impartial observer takes his claim especially seriously. It is hard to do so when there has been almost no welfare reform to assess. The Work Programme was designed to help older people and the long-term unemployed into work. Last year, the House of Commons Work and Pensions Select Committee pointed out that 70 per cent of those people enrolled have failed to find long-term employment. The principal effect of replacing Incapacity Benefit with Employment Support Allowance (ESA) was that tens of thousands of claimants were reassessed as fit for work despite serious doubts that they were able to do so. The waiting list for the capability assessment stretches into the hundreds of thousands. Of those decisions that go to appeal, 40 per cent are overturned. The number of disabled people returning to work has been falling.

Which gets us close to the nub of the matter. The Chancellor has become increasingly exasperated that Duncan Smith’s promised savings to the budget never materialised. It may have been needless bravado, in anticipation perhaps of a second coalition, to have demanded a further £12bn in cuts to the welfare budget but the crucial point is that Osborne had clearly lost confidence in the efficacy, let alone the speed, of Duncan Smith’s reform programme. The original plan, from 2010, was that the government would take £19bn a year out of the social security bill by 2015. The realised savings were just £2.5bn a year. Tax credits cost £5bn more than expected in the last parliament.

This was too great a temptation for a Chancellor who needed the money and began the chain of events that led to Duncan Smith’s resignation. Osborne’s £4.4bn raid on the tax credit bill had fallen over in a rebellion in the House of Lords in October 2015. In his budget in March, Osborne looked to find some of the money in cuts in benefits for the disabled. Duncan Smith had replaced the Disability Living Allowance with the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) but he was missing all his targets. Claimants had not received the promised extra support, the numbers claiming had not increased and the savings had not accrued. Indeed, in the days that followed the Budget, ministers began to use the fact that spending on the disabled had gone up as their justification for the cut.

There is an error here which is characteristic of Duncan Smith’s time in office, perhaps characteristic of Duncan Smith himself. When he was pressed for savings, Duncan Smith went ahead with turning the ESA from a pilot into a national scheme, even though his own independent reviewer was opposed to the move. It was not long before appeals overwhelmed the system. What happened with the ESA was repeated with PIP. The promised savings never appeared. When Osborne demanded the money anyway, Duncan Smith at first agreed, then changed his mind and left.

He left with a vicious, although curiously contradictory, critique of the government’s deficit reduction. Duncan Smith appears to want the cuts relaxed and yet the deficit to be paid down more rapidly. Quite how he intends to draw a square circle he is now at liberty to work out. In fact, to concentrate solely on the welfare component of the income of the less well-off is to do the government as a whole a disservice. The legacy labour market reform of this period will be the National Living Wage, which was introduced on 1st April. If the effects of higher wages are added into the regressive impact of budget measures, the government’s record is much more creditable. This is a good story for the government to tell although it is not a story that features Duncan Smith. The National Living Wage was so entirely Osborne’s reform that the Work and Pensions Secretary found out about it at exactly the same point as the rest of us, which is when it was announced in the House of Commons.