William Beveridge discusses his report at the Ministry of Information. Photo: AP/Rex/Shutterstocks

On 30th November, 75 years ago, in the middle of the Second World War, an anticipatory queue formed on London’s Kingsway, the then headquarters of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Barely a fortnight earlier, Winston Churchill had ordered that the church bells be rung in recognition of Montgomery’s victory at El Alamein. It was the first domestic cause for rejoicing after three years of a war where there had been nothing to celebrate aside from the retreat from Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, and stoic defiance of the Blitz. It was El Alamein—the first victory—that brought forth Churchill’s famous declaration that “Now is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is perhaps the end of the beginning.”

The lengthening queue on Kingsway, however, was not focused on the end of anything; they were after a new beginning. They were there for the somewhat unlikely purpose of buying an often-immensely technical 300-page government-commissioned report, written by a retired civil servant, with the uninspiring title “Social Insurance and Allied Services.”

Much of the report was as hard going as the title suggests. But its 20-page introduction and 20-page summary, which were sold as a cheaper cut-down version, punchily dug the foundations on which the post-war welfare state would rest. These parts of the report were stuffed with inspirational rhetoric—“five giants on the road to reconstruction,” “a revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching”: language that no government report, on any subject, has rivalled since.

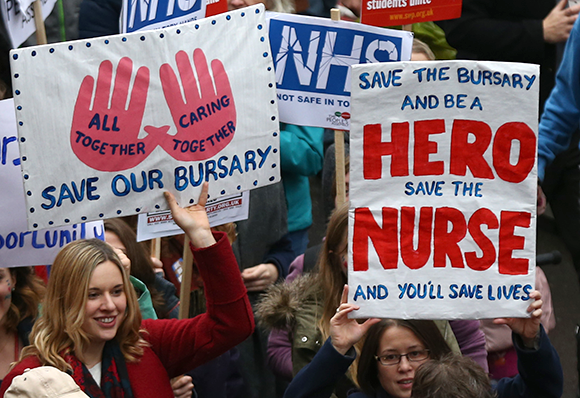

In the context of the welfare state today, after seven years of austerity and with more to come, it is pretty hard to imagine news about anything other than cuts. The NHS is in the midst of the biggest squeeze in its history. Social care is in crisis. Spending per pupil is due to stop rising, and to fall in real terms. And entitlements to working age benefits—having been cut—are due to be cut again. Even back in the New Labour years, when the government was mobilising serious resources to make work pay and avoid the poorest families falling behind, there was almost an element of embarrassment about the endeavour. Certainly, nobody queued down Kingsway, Whitehall or anywhere else to hear about Gordon Brown’s tax credits, which were expressly designed to disguise a poverty-reduction programme as tax cuts, the calculation being that the war on want would be unpopular and so must be waged with stealth. Compared to 1942, it is another world.

![article body image]()

Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies

The author of the report that caused such a stir 75 years ago was William Beveridge, an egotistical 63-year-old who already had more careers behind him than most ever enjoy—not just in Whitehall, but also as a journalist, broadcaster, permanent secretary, and head of both the LSE and University College, Oxford. He seemed to switch opinions almost as often as he did jobs. At times he held distinctly free-market views, but advocated for dirigiste planning during both world wars. He sometimes spoke in generous terms about social welfare, but at others of the economic necessity of “the whip of starvation.” Just four years before his report, Beatrice Webb, the great Fabian reformer, recorded his view in her diary after a walk across the Hampshire downs, that “the only remedy for unemployment is lower wages… he admitted, almost defiantly, that he was not personally concerned with the condition of the common people.” And he had something of the crank about him. The young Harold Wilson, for a time Beveridge’s researcher, recalled having in the 1930s to talk him out of a theory that it was the “sunspot” cycle—solar eruptions which supposedly bore on crop yields—that chiefly explained unemployment.

When he was appointed, it must thus have been tough to know how his report would turn out. In 1942, however, he was to prove admirably clear about what he wanted to do. His report did indeed offer—as was trumpeted on publication day by newspapers as diverse as the

Daily Telegraph and the

Daily Mirror—“cradle to grave” social security. It really did promise a clean break with the hardships not just of the war, but with the pre-war past. And the British welfare state that it set out in blueprint is, for all the challenges that it faces, still with us today.

Beveridge’s core aim was to tackle the poverty that had so scarred the 1930s, though he dubbed poverty “Want.” The 1930s were the days of mass unemployment, the Jarrow march, and the deeply loathed household means test that could see a family lose benefit if a child got a paper round. He proposed to solve that by building a new system of social insurance that would support a vastly improved benefit system.

But “Want,” he declared—and he was fond of both lists and giant capital letters—was but one of the “five giant evils on the road to reconstruction.” The others being “Disease, which often causes that Want… upon Ignorance which no democracy can afford among its citizens, upon Squalor… and upon Idleness which destroys wealth and corrupts men.”

And to make his new system of social security work, he wrote in “three assumptions”—things that had to happen, outside of his report, to allow it to happen. Specifically, there would be a national health service, available to all and without a charge of any kind. That there would be children’s allowances, which we would now recognise roughly as child benefit. These were to be funded from general taxation, not the national insurance contributions that underpinned the rest of his system. And there would be “full use of the powers of the state to maintain employment and reduce unemployment.”

So there it was. A comprehensively new social security system, involving everything from maternity to funeral grants. A free-at -the-point-of-use NHS. An attack upon Ignorance—better education. An assault upon Squalor—replacing slum housing. And a policy of full employment. A pretty much all-encompassing vision, which pretty well came to pass.

Outside the Treasury, where the chancellor Kingsley Wood did his damndest to kill it off, the reception was rapturous. Even Churchill in some moods favoured the vision, though at other times he fretted over the costs. As a result, some planning was done, but none of it was actually to happen—other than Butler’s great 1944 Education Act—until after the war was won. But the political power of the Beveridge promise was nonetheless extraordinary. In HMSO folklore, nothing outsold Beveridge’s 600,000 copies until the Denning report, on the more obviously sexy subject of the Profumo scandal 20 years later. The BBC broadcast details of “The Beveridge Plan” round the clock in 22 languages, and summaries were dropped into Nazi-occupied Europe. A commentary found in Hitler’s bunker after the war declared it to be “no botch-up… and superior to the current German social insurance in almost all points.”

In the words of José Harris, Beveridge’s brilliant biographer, the report’s spectacular impact was “a matter of both luck and calculation.” The luck included the fact that it landed just after El Alamein. The calculation was the way Beveridge and his allies had trailed it, long before the days of spin doctors, and, of course the Bunyan-esque prose with which he painted his vision—Beveridge was, after all, originally a journalist.

For all the daring, there was continuity as well as change in the report. The Beveridge system can be traced to the first Edwardian moves towards social insurance—in which Beveridge had had a hand—and to assorted municipal experiments, from the communal healthcare in Aneurin Bevan’s Wales to the bold council housing schemes of Herbert Morrison’s London County Council. But while all these models and many other ideas had been swirling around well before the war, it was Beveridge’s report, in the wonderful phrase of Paul Addison, that provided “the prince’s kiss.” The one that gave them life. He distilled the spirit of the lot.

***

Here is not the place to tell the tale of how Beveridge’s vision of a modern welfare state was constructed nor the struggles that have followed over the succeeding 75 years, in which it steadily expanded to take up a much larger slice of a far bigger economy (see chart opposite). All of that is covered in my newly-updated book,

The Five Giants. What I want to do here instead is to ask what on earth the Beveridge of 1942 would have made of the welfare state as it stands, 75 years on.

It is not an easy question to answer with any precision, as so much has changed that he simply could not have foreseen. When he reported, the worry was not about an ageing population, but a declining one, and in his view it fell to “housewives as mothers” to put this right through their “vital work… in ensuring the adequate continuance of the British race.” Women may have been pouring into factories and flying unarmed Spitfires in the emergency of war, but expectations were still shaped by the pre-war world, where only one married woman in eight had worked. Thus, for married women, “provision should be made... with reference to the seven [the seven who did not work] rather than the one.” So married women gained less benefit in their own right than men.

Gender is only the start. In 1942 the school leaving age was 14, and a vanishingly small proportion, just 3 per cent, of 18 year olds went on to university. Income tax rates were high. But only the decidedly better off paid any income tax at all. Britain still had a global Empire, but it had neither a remotely global economy nor any significant Commonwealth immigration. The closest thing Britain had to a computer was being operated in secret by Alan Turing, the BBC’s fledgling television service had been suspended for the war, and relatively few homes had a telephone. We were much younger: with fewer than 200,000 people aged over 85, against 1.5m today. And we were much poorer, with average inflation-adjusted income per head around a quarter of today’s figure. And so on and so on.

But with all that said, Beveridge would recognise and be proud of the National Health Service, which, a few charges in England aside, fits his ideal, although he would be amazed at its size. He believed that the costs would fall once a mighty backlog of treatment had been dealt with. Instead, as in every other developed country, expenditure on endlessly-evolving modern medicine has risen faster than the economy. But healthcare, the overwhelming bulk of it still coming through the NHS, now consumes around one pound in 10 of our much enlarged national income. He would be much less happy about the condition of its Cinderella sister, social care. The 1945 Labour government claimed to have “abolished the Poor Law.” But its shadow lives on in the way social care remains first “needs tested”—a certain level of disability is needed to qualify—and then means-tested. If Beveridge was around today, cracking that and integrating this neglected service with health would be a target.

He would recognise and broadly approve of the basic state pension, although he would have been decidedly cross at the way its value was allowed to sink for 30 years after Thatcher broke the earnings link in 1980. He would, however, endorse the cross-party way in which over the last decade—via the Turner Commission, Labour legislation, coalition implementation, and, so far, Conservative preservation—it has been rebuilt as what he originally intended: a near-universal minimum platform on which private saving can be constructed. Auto-enrolment into pensions wasn’t even an idea back in 1942. But this form of personal provision on top of that from the state would decidedly appeal to this liberal statesman.

Beveridge would approve, at least in principle, of welfare-to-work programmes. His report recommended that men and women “unemployed for a certain period”—six months in periods of average unemployment, longer when it was higher—“should be required as a condition of continued benefit to attend a work or training centre… to prevent habituation to idleness and as a means of improving capacity for earning.” Those recommendations were not implemented in the days of full employment after the war. They seemed unnecessary. It was to take until the later 1990s, and in a much changed labour market, for welfare-to-work properly to take off.

He would, however, be mortified that, 75 years on, we still haven’t solved what he dubbed “the problem of rent.” He devoted nine pages to it while acknowledging that the solution he proposed was inadequate. He would be appalled at the way rising private sector rents have turned what is now housing benefit into the equivalent of running up a down escalator—the bill rises remorselessly even as the quality of accommodation covered descends—in a housing market that the Conservative communities secretary Sajid Javid has candidly described as “broken.” And he would, of course, have been horrified that seven years of austerity have seen the return of food banks, the modernised equivalent of the old soup kitchens—75 years after his plan to abolish Want.

![Unemployed men queuing at a labour exchange, October 1931. Photo: Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty Images]() Unemployed men queuing at a labour exchange, October 1931. Photo: Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty Images

Unemployed men queuing at a labour exchange, October 1931. Photo: Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty Images

Unemployed men queuing at a labour exchange, October 1931. Photo: Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty ImagesBut when it comes to the way Want is remedied today, Beveridge would be bemused at how far means-testing—through tax credits, housing benefit, and now universal credit—now extend up the income scale. This has been one of the most enormous changes since his time, occurring over the 1990s and 2000s as the emphasis on the benefits system shifted from supporting people on condition they did not work, to supporting them to be in work, a response to the way globalisation was driving down wages at the lower end. With his knowledge of the 1930s, he hated means tests on similar grounds to Frank Field who has repeatedly argued that they “promote idleness, encourage dishonesty and penalise savings.”

But it is the flipside of all the means-testing that would have alarmed him the most—a spectacular erosion of the contributory principle, which had been the rock on which Beveridge built his plan. “Benefit in return for contributions, rather than free allowances from the State, is what the people of Britain desire,” Beveridge declared. Today, National Insurance is still collected on a vast scale—it is the government’s second largest source of revenue after income tax. But the basic state pension aside—and even there the link is diluted—the connection between contributions paid and benefits received has come close to disappearing. Since the 1990s, insurance-based unemployment benefits have only been paid for six months, after which the means-test bites; more recently, other insurance-based benefits have been similarly curtailed. All of that would have met with Beveridge’s stern disapproval.

So there are as many negatives as positives on our brief and selective score card that we have presumptuously filled out on behalf of the Beveridge of 1942. But then the welfare state never was—or never should have been—something handed down on tablets of 1940s stone, never to be tampered with. It has, inevitably, had to adapt to the changing world. And there have been big advances as well as setbacks down the years.

There is, for example, now a huge range of benefits for disabled people never envisaged in the 1940s. There has been the massive expansion in schooling and—notwithstanding the tuition fees row—a mighty explosion in higher education. Having spent next to nothing on early years and childcare 20 years ago, the UK has today one of the highest levels of spend in Europe. In the 1940s, and for decades afterwards, the great worry was the elderly poor; today, while there are still some poor pensioners, the elderly are the social group least likely to be at the bottom of the income distribution, a remarkable story of progress.

While the welfare state is under all sorts of financial stresses and strains, even after austerity it takes roughly two-thirds of government expenditure, and around a quarter of national income, just as it has since the 1980s. The composition of that spending has changed—parts have shrunk (free teeth and specs, for example) or even vanished. But new limbs have been added, and the beast is still alive. The prognosis for it in the coming 75 years, however, will depend on the argument for it continuing to adapt in changing times. The most pressing question for its survival is not what the 1942 Beveridge would think about this or that aspect of today’s welfare state, but how a modern-day Beveridge might set about restoring the system’s popular appeal.

In the era of ration-books and emergency wartime taxes, Britain became more equal, which made the “all in it together” spirit required to build the welfare state that bit easier to achieve. But over more recent decades inequality has widened hugely again. Inheritance has begun to bear more heavily upon an individual’s life chances, in ways that would have stunned and troubled Beveridge—he would, reasonably, have assumed it would continue to become less important, as it had already been doing for decades by 1942. Even in the egalitarian 1950s, the truly comprehensive social insurance system Beveridge desired was never quite achieved. It would be a much more difficult sell in a world where the poor struggle to pay the premiums, and the rich feel they don’t need the cover.

![article body image]()

Would he even try? The one area in which he might is social care, where patchy and inadequate provision is fuelling the fear of financial ruin. Here a cry for the pooling of risk across society might, if put with flair, still be popular.

A modern-day Beveridge would be intrigued by the argument that because automation will soon destroy jobs on such a scale, it is time to set the welfare state on entirely new principles, by offering everyone a so-called universal “citizen’s “ or “basic” income. But with his “something-for-something” understanding of popular morality, he’d be unlikely to regard a free-for-all stipend as a way to entrench legitimacy. And he would be quick to spot that such a policy would be a decidedly costly stretch, requiring stiff levels of taxation—for which there is absolutely no evidence that the British electorate would vote.

As a wordsmith, Beveridge would be acutely sensitive to the role of language in charting a course through all the modern-day challenges. Although widely seen as the founder of the modern “welfare state,” he in fact refused to use the term, disliking its “Santa Claus” connotations. He would today be even more dismayed by some of the language around it, and the effect on policy. “Social security”—Beveridge’s great goal—has fallen out of the lexicon. Politicians of all parties now talk about “welfare,” and quite often deliberately conflate everything from the contribution-based pension (by far the largest single element of the £212bn bill), to child benefit, in-work benefits, and means-tested help for the workless, with the latter, at most, accounting a sixth of the bill. The meaning of the word “welfare” has been turned on its head. It has little to do with faring well. Rather, it has become a term of abuse. To be “on welfare” is to be on the wrong side of the tracks or on “benefit street.” One thing those politicians who truly believe that “we are all in this together” could do is reclaim the language of “social security” and the sense of collectiveness that goes with it.

One of the many modern problems which was not a challenge in the 1940s is inter-generational inequality. Even to the extent that it was, it was the old and not the young that were the worry. But in the gap that today yawns between the generations in the opposite direction, a modern-day Beveridge might spot an opportunity—to re-emphasise something the welfare state has always done, which is redistribute not just from rich to poor but across the individual, and family, lifecycle.

The welfare state continues to educate and support its children, as it always has. Having seen them through birth and the early health interventions that are crucial for their future, it seeks to pick up the minority in their middle years for whom life goes wrong in myriad ways. And when these people—and their more-fortunate peers—are older, it tries to ensure they have a basic state pension: having provided, on the way, incentives and assistance to help those who can build something better than that. And it assumes that those older people, and their children, and their grandchildren, will repeat the enterprise—because the older generations fret as much about the younger generations, as the younger generations do about their parents and grandparents. Whether the question is health or housing, education, employment or poverty relief, the welfare state does all this far from perfectly, and occasionally very badly. But most individuals and families would, surely, still prefer for their own lives to unfold in a world where the welfare state was there at moments of vulnerability, rather than live in the alternative—a world where everyone is for themselves, for good, or ill, or very ill.

A modern-day Beveridge would thus likely aim to foster understanding of the welfare state’s continuing role as an unwritten inter-generational contract. By doing that, he just might be able to encourage taxpayers’ willingness to stump up the funds that the system continues to need.

For the single thing that Beveridge would be crystal clear about is that if the British people, to use his repeated phrase, still want in very changed circumstances a decent system of social security and a wider set of “allied services”—the NHS, education, decent housing for all—then they have to be prepared to advocate, fight, vote and pay for it. My favourite single quote from Beveridge is this. “Freedom from Want cannot be forced on a democracy or given to a democracy. It must be won by them.” As true now as it was then—when people were queuing up for it.