More by James Harkin: South Sudan—the stillborn state

On 3rd January of this year, Islamic State (IS) released a video that belongs to what has become a familiar gory genre. A balaclava-clad Briton, flanked by four other masked jihadis, stood behind five kneeling men from Raqqa, the IS-held city in northern Syria. The prisoners were softly mouthing prayers. In a slick montage cut with chanting, some of the five, clearly under duress and likely having been tortured, confessed to being spies and journalists for Britain. They admitted to taking photos of IS positions in exchange for money, setting up an internet café to gather information, and working for outlets such as the BBC. After their captors’ customary tirade against the west, the prisoners were each shot in the back of the head.

The video captured the sharp end of Syria’s information war. Deadly things happen every day purely because of how they will look; people are killed because of how they have made things look. There can be no disentangling of the substance and the spin: one feeds back into the other. This is a conflict where attempts to shape the flow of information determine where blood gets shed, and the flow of blood in turn restricts the movement of information. Every major incident brings with it rival media footage and the roar of claim and counter-claim. The attack on a UN aid convoy near Aleppo in September, which killed 20 civilians, is a case in point. One set of videos emerged to suggest that the Syrian regime or its Russian allies were responsible. Just a few hours later, the Russians produced their own grainy film, which purported to show it was not their doing. That footage warped perceptions until what now looks like irrefutable evidence finally emerged that this was indeed a Russian or Syrian airstrike.

In this war, even supposedly “non-lethal aid,” to assist in the so-called battle of hearts and minds, can easily have lethal consequences, and the consequences of lethal force are often impossible to gauge. This is never more so than in Raqqa, the conflict’s heart of darkness. It is a year since Parliament voted to approve airstrikes on the city after the IS attacks on Paris. David Cameron, then Prime Minister, promised that bombing Raqqa would cut the head off the terrorist “snake.” Despite sustained bombardment, this has not happened. Donald Trump, US President-elect, has only promised to intensify the campaign. (In his words, “I would bomb the shit out of ‘em.”) Judging the success of airstrikes requires on-the-ground information. But there is no free journalism in Raqqa, and nobody can actually see what is going on.

I know a photojournalist from Raqqa who is the brother of one prisoner in the video. I spoke to him shortly after it appeared, and he was still in shock. Along with other exiled activists, he had been mentioned by name in the video as a handler for the “spies.” He had been writing in hostile terms about IS from the start. But since he had fled the city—he now lives in Istanbul—murdering his brother was the only way the group could get to him.

A little over six weeks before the video was released, Mohammed Emwazi, the Briton nicknamed “Jihadi John,” had been killed by a drone strike in Raqqa. Always obsessive about security, IS was now paranoid about intelligence leaks. The video was a warning to any locals who might be tempted to give up the locations of the group or its militants. Share information, it said, and we will catch you. And this will be your fate.

But it is not only IS that is prepared to sacrifice lives for the sake of changing perceptions. In the first years of Syria’s conflict, both local and foreign reporters were kidnapped and killed by all sides; independent journalism all but died. One way to get information out of rebel-held areas was to give media equipment to rebels. Over the last five years, the United States, Britain and other western governments have funnelled millions of dollars’ worth of satellite phones, cameras and laptops to young activists opposed to President Bashar al-Assad. No longer ancillary to the action, this equipment became a weapon that could capture and even choreo- graph events on the ground. It was dangerous work. A good many Syrian activists with cameras have been killed by regime forces; when the activists turned their attention to IS, scores more became targets for assassination.

Only a hundred miles east of Aleppo and a short drive south from Turkey, Raqqa rests on the north bank of the Euphrates. People have lived there for a long time. Raqqa was the site of an ancient Greek city, and after that the summer home of an early Islamic caliph. The city has been razed to the ground before. After being sacked by the Mongols in the 13th century, it ceased to exist for a while before it was revived during the Ottoman empire. In modern times, Syrian tourists ambled around its churches in the temperate weather, and viewed the striking gate which is all that remains of its old city wall. In the decade before the uprising broke out in 2011, Raqqa’s population had swollen to around half a million. Locals began to call it “Little Paris.”

Not any more. In March 2013, before IS had been established, a coalition of largely Islamist militias, including al Qaeda, ousted the Syrian army from the city. At first, freedom from Assad was invigorating. But amid factional infighting among rebel groups and airstrikes from the Syrian regime, it quickly degenerated into chaos. Nursing a visceral hatred for journalists, IS moved to throttle local and international media as it cemented itself in power. In January 2014, after an attempt by other Syrian rebel groups to gang up on IS backfired, the group decided it needed its own base in the country. Raqqa and its surrounding province became its de facto capital, and the group set about building a state: providing services for its adults, sweets and bouncy castles for its children and prisons for its political enemies. When it began blowing up Shia mosques and desecrating churches, the minorities left for Turkey. So did most of the remaining activists.

For many people, however, life under IS had its advantages—at least at first. Those left behind, many of them the poorest of the poor, were joined by refugees from elsewhere in Syria, fleeing airstrikes or anarchy in Homs and Aleppo. In 2014, activist Hamza Sattouf told me that many of his friends from Homs were flocking to Raqqa. Whereas in rebel areas, “there are a lot of thieves,” he said, in Raqqa anyone could leave their belongings lying around. The only drag were the checkpoints on the way out, where terrifyingly young militants would check your mobile phone for evidence of anything from political activity to porn.

Long before anyone else, IS understood that the real game in this new media war was to control the message. It used the internet to invite thousands of jihadis and their girlfriends from around the world to help build the new state. In summer 2014, I was in a foxhole with Kurdish militia on the border of Raqqa province. When I asked the commander if he knew anything about the IS militants attacking his position, he told me that the village on the other side of the frontline had been repopulated with Chinese fighters and their families. “The Uyghur people, I think,” he said, shrugging his shoulders quizzically.

The week before that, I had phoned a British jihadi in Raqqa called Kabir Ahmed, who waxed lyrical about the cosmopolitan feel of the city. “It’s like a dream. One day we eat Eritrean, the next we eat Pakistani.” Ahmed’s dream ended abruptly; five months after we spoke he became, according to IS media, the group’s first ever British suicide bomber. The party was soon over for his fellow jihadis, too. After IS slaughtered the American journalist James Foley and other western hostages in August 2014, President Obama took the offensive and the first US aircraft took off to hit Raqqa in September, shortly to be joined by a hastily assembled Arab coalition. A year later, they were joined by Russian planes; two months after that Britain joined the club.

F or IS militants in Raqqa, much of the day is spent scanning the sky for drones and planes. But it isn’t only foreign jihadis who live in fear. Marwan Hisham is the pseudonym of a writer from the city with whom I have been in touch for a few years. Hisham went back to Raqqa in autumn 2015 and spent months quietly taking the temperature there before getting out in January. He estimated there are at least 300,000 civilians still in the city. He said that the panic induced by aerial bombardment from a dozen countries is “unbelievable… every night there I thought I was going to die.”

The raids often begin at midnight; the cycle can go on for an hour or more. Even strikes five kilometres away are felt inside the city. If IS fighters are thought to be living in a flat, it gets obliterated and the houses around it are often badly damaged too. According to Hisham, the Russian sorties are the worst. The bombs from the coalition (the US, the UK, and other western and Middle Eastern countries) arrive from drones or planes that fly so high they cannot be seen; they fire 10 or 20 rockets in a few seconds and then disappear. The Russian planes fly lower and are visible; they sometimes bomb and circle repeatedly for up to half an hour. “It’s all about terrifying people.”

Through the fog of propaganda, it is impossible to know what the citizens of Raqqa make of all this. In the beginning IS was ostentatiously polite to the locals, says Hisham, winning it goodwill. Some people he spoke to justified working with IS on a religious basis, but mostly they were just grateful that it imposed order. IS’s rules are harsh and primitive but clear and therefore predictable. As the group finds itself squeezed, however, it has been tightening the ideological screw, trying to grow a new generation of Islamists. Courses in Sharia, once reserved for people arrested for misdemeanours, have now been extended to anyone who has a job. They consist largely of guilt-tripping local men into fighting for IS. In time, Hisham thinks that its indoctrination courses will be extended to almost everyone. “Most people are in the ‘grey area’ where they can’t decide,” is his conclusion. “IS will stay, they think, so they have to accept it.”

They have little choice. Late last year, IS began to stop everyone from leaving Raqqa except the very old or clearly sick. More recently, it has started to behead people-smugglers and display their bodies at intersections. Some fear that conscription is on the cards. The airstrikes make IS increasingly paranoid about spies. Its masked security police, known as “amnis,” hover around internet cafés and can search anyone’s phone at any time.

Soon after IS took over Raqqa, the city became an information black hole. Hungry for news, the international media fastened on a collective called “Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently” (Raqqa SL), which was working to fill the gap. At first the material its members published online was mostly culled from IS—gloomy pictures of black-clad gatherings or children with bandanas toting Kalashnikovs. Like the later salacious western tabloid coverage of IS, the difference between the group’s propaganda and the counter-propaganda was hard to spot. But Raqqa SL became more daring—publishing more of its own photos and information from inside the city.

While foreign journalists often imply that Raqqa SL’s core members are still in the city, none of the activists I know think this can be true. The space required to write and edit has been squeezed out of Raqqa. Instead, the group’s members tap friends and relatives who remain, asking questions and scouring Facebook pages. It is a perilous business—and not only for those directly involved. At first, IS left families of known activists alone but it soon began a crackdown. In 2015 it murdered the father of Hamood al-Mousa, one of the group’s leading lights. Others who may or may not have worked with Raqqa SL have been killed too. Even Turkey is no longer safe. Several members of the group have been assassinated by IS in the Turkish border city of anlurfa.

The American Committee to Protect Journalists has given Raqqa SL an award. Among Syrians, however, the group is not universally popular. In Gaziantep, a Turkish city near the Syrian border that is home to many opposition activists, I met the activist Zein al-Malazi, a long-time foe of IS. When IS was rubbing alongside rebel groups in Aleppo in 2013, she remembers, its members were so puritanical that they left the room as soon as she came in. But Raqqa SL, she told me, is generally considered a “Facebook event,” whose chief consequence is that it gets people killed. “Raqqa SL are media heroes,” she said, but “with a very small impact at the community level.”

One activist from Raqqa, who knows and likes members of the group, nonetheless accuses it of publishing publicity-seeking propaganda with no reporting depth. Like other Syrians I spoke to, he blamed the international NGOs and media who were encouraging daredevil agitprop with money and garlands. (Several activists told me that Raqqa SL receives funding from an American non-profit called Democracy Council among another western sources. Democracy Council refused to comment for this article despite several requests.) Another rebel activist I met in Gaziantep, who runs a network of confidants in neighbouring Deir ez-Zor, was unable to contain his anger. “This is bad work, what they do, and not journalism. To do that you should be safe—very safe. Anyone can connect with young guys and teenagers in a bad situation in Syria and pay them a few hundred dollars a month. Raqqa SL are responsible for all these deaths. And after a year and a half what is the impact? IS killed their people.”

One of the other men mentioned in the January execution video used to work with Basma, the now defunct media production arm of a British-led, Foreign Office and US State Department-funded agency called ARK, which moved into Turkey in 2012. Through Basma, ARK started paying young Syrians to make short films campaigning against the regime, some of which were then beamed back into the country on rebel-friendly channels or on Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya. ARK’s leading managers all have defence and security backgrounds; there are also policy advisors, “psychological operations” specialists, and former British soldiers.

While money for smart young Syrians is always welcome, one result was to fuel suspicions that mainstream journalists were under malign foreign influence. Some of those concerns appear to be well founded. Several years ago a Syrian activist sent me internal ARK briefing documents that implied the organisation was drawing on its network of Syrians to gather intelligence on Islamist groups for an unknown client. For her efforts to make these documents public she received an intimidating phone call from a local American Embassy (which she played me) and an even more intimidating visit from Turkish police. A clue to the identity of the client lay in an accompanying email apparently written by a British Lieutenant Colonel, who was forwarding those briefings to his opposite number at United States Military Command (Centcom). The email referred to “a couple of interesting documents from ARK, the contractor involved in Op VOLUTE/Project Basma in Syria,” and recommended additional funding for the project from the US. “It would be reinforcing success for comparatively modest costs,” it said.

Whatever the truth of the spying allegation, the idea that Syrian activists have been working for foreign governments has been enough to get dozens of them kidnapped and killed. A week before that January execution video was released, a well-regarded documentary maker called Naji Jerf was assassinated in Gaziantep. He had been making videos for Raqqa SL; before that, he was a manager at Basma. According to my writer contact Hisham, Raqqa SL is widely read in the city’s internet cafés. “A good deal of its information is credible, but much is also absurd.” He also accuses it of carelessness. “This is not work, not journalism; it is not professional at all. Those guys they say work for them, they pay them money to risk their lives.”

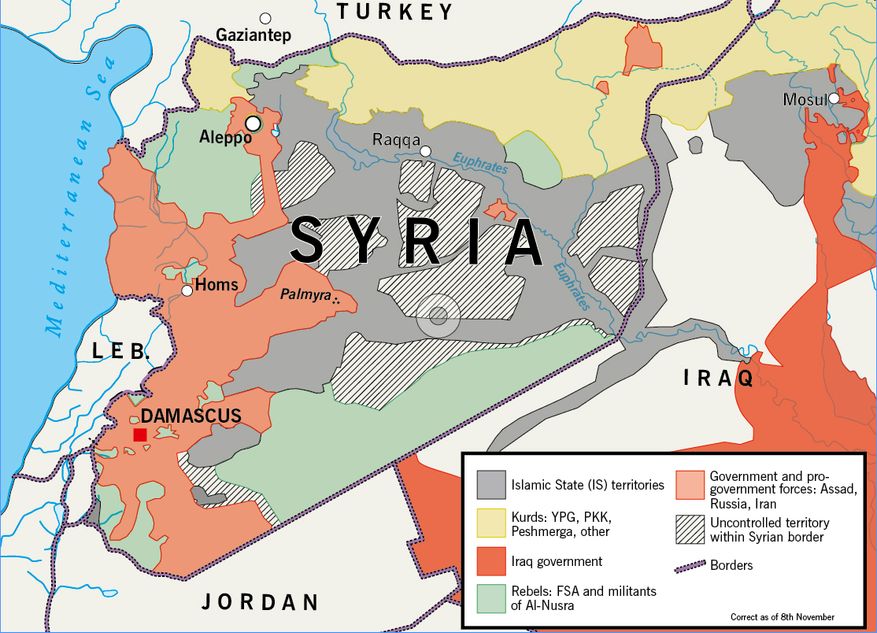

For the moment, the perception that IS has worked so hard to foster among the people of Raqqa—the belief that it is not leaving any time soon—may be valid. Over the border in Iraq, the fight is under way to free Mosul from IS hands. But at the time of writing, the Iraqi battle plan involves opening an escape corridor for IS fighters to flee to Syria—which would only reinforce its manpower in Raqqa. In any case, the group would do anything to avoid losing its Syrian capital, says Hisham—while he was there it was digging defensive trenches around the city. Last year, the prospect of American largesse ushered into existence a rebel militia called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which claims it will take the fight to IS. But the SDF is only a fig leaf for the YPG Kurdish militias, whose agenda is to keep Islamists out of their own areas. On 6th November, the Kurdish-led SDF launched a fresh military campaign with 30,000 men “to isolate Raqqa” from the North, likely because the Americans wanted them to synchronise with events in Mosul—and in return for promises of heavier weaponry and more autonomy for Kurds.

At the fulcrum of Syria’s war, Raqqa has become an international card game in which all sides—from the Turks to the Syrian Kurds to the Americans to the Syrian rebels to the Syrian regime—bluff towards their own ends. Not only are the city’s people at the mercy of IS, they are in the sights of just about every country in the civilised world. In recent months, the information war has reached fever pitch as the Syrian regime redoubles its air war on rebel-held eastern Aleppo. Western-friendly media activists report that the Syrian regime and its Russian allies are deliberately targeting civilians; in turn, the strategy of the Russians is often to sow confusion. Neither side makes it clear that this is a war of two or more sides; it is as if they are living in alternate worlds. Truth has become a relative concept; everyone has an axe to grind.

The lack of independent journalism on the ground means that anyone can say anything they like. Russian officials have dismissed the idea that their warplanes might have caused a single civilian casualty. Yet at the end of September, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights counted 3,804 civilian deaths from one year of Russian strikes. The same organisation estimated that coalition airplanes had caused 611 civilian deaths in two years. The Russian toll is much higher, but since its bombing runs are spread over a much wider range of targets (the coalition is focused on IS, while the Russians are bombing IS and other rebel militias too), we can assume that a higher proportion of the coalition casualties happened in and around Raqqa.

For the first 15 months of its bombing campaign, Centcom also denied that US strikes had caused civilian deaths. Beginning in November 2015, however, it owned up that in August, three Raqqa residents had been killed in a failed attempt on the life of Junaid Hussain. Hussain, a British jihadi whose ill-judged tweets about being a terrorist super-hacker pushed him to the top of the coalition’s hit list, was killed in another strike shortly afterwards—another example of the lethal consequences of the propaganda war. In July this year, there was another incident near Manbej, then an IS outpost close to Raqqa province, in which at least 56 civilians appear to have been killed by coalition planes.

But while the Russian and Syrian onslaught on rebel-held east Aleppo is in the news every day, there was little media outcry after the Manbej bombing. There were no activists with cameras on the ground to report it (although Raqqa SL issued a statement castigating the coalition for causing so many deaths). IS produces its own videos of the aftermath of bombings in Raqqa, but no one in the outside world pays them any attention. The danger is that the images of death and destruction that appear on our television screens exist in a kind of feedback loop—giving us the news that our governments want us to hear, and leaving out what they don’t.

Meanwhile, Raqqa is being pounded by all sides. In August, the Guardian reported that Kadiza Sultana, one of three schoolgirls from Bethnal Green who joined IS in 2015, had been killed on 22nd June. From sources in Raqqa, her family were told that she had been living in a flat above a “financial office” in the city which had been hit by a Russian airstrike. But is that right? The airstrikes on Raqqa at that time were identified by Raqqa SL as Russian. Yet as an opposition media group, Raqqa SL might be more inclined to blame attacks on the regime-supporting Russians. The more circumspect Syrian Observatory cannot say who carried out the strikes. Centcom’s data for that night referred to an attack by US or UK airplanes on a “finance center” in Raqqa. It seems likely Sultana was killed as collateral damage from an American bomb or a British Reaper drone. The independent monitoring group AirWars told me that if Sultana’s flat really was above that IS financial office, then “it’s almost certain the coalition was responsible.”

Nothing coming out of Syria can be taken on trust, and the people left in Raqqa have nobody to plead their case. With their eyes fixed on the afterlife, IS’s zealous international volunteers are not deterred by the prospect of martyrdom. But many of the young locals have signed up for checkpoint duty for money or status. They want to get on and live. Around 20 people from Marwan Hisham’s neighbourhood alone, however, have already been killed fighting for IS. At the end of October the Syrian Observatory estimated that the bodies of 300 Syrian children (so-called “Cubs of the Caliphate”) had been returned to Raqqa, having been killed in IS’s defence of Mosul.

The photojournalist whose brother died in the January video told me that while he sympathised with France after the Paris attacks, killing people from the air was hardly the answer. “In Raqqa there are a lot of French IS fighters, but we don’t say all French people are jihadis. In Raqqa, too, most people are innocent.” Raqqa’s tragedy is that it has become a punchbag for everyone’s impotent frustrations about IS. That situation might only get worse under President Trump.

Using expendable Syrians for media and intelligence may yet have far-reaching effects. Marwan Hisham says the people of his native city are being backed into a corner. “I feel very sad. I know those people, I was born there, lived there all my life—they [the major powers] are not giving them any choice. Now it’s all about revenge… In the worst-case scenario, the people of Raqqa will join IS. At the very least they will hate the west, and they will hate the world.”

On 3rd January of this year, Islamic State (IS) released a video that belongs to what has become a familiar gory genre. A balaclava-clad Briton, flanked by four other masked jihadis, stood behind five kneeling men from Raqqa, the IS-held city in northern Syria. The prisoners were softly mouthing prayers. In a slick montage cut with chanting, some of the five, clearly under duress and likely having been tortured, confessed to being spies and journalists for Britain. They admitted to taking photos of IS positions in exchange for money, setting up an internet café to gather information, and working for outlets such as the BBC. After their captors’ customary tirade against the west, the prisoners were each shot in the back of the head.

The video captured the sharp end of Syria’s information war. Deadly things happen every day purely because of how they will look; people are killed because of how they have made things look. There can be no disentangling of the substance and the spin: one feeds back into the other. This is a conflict where attempts to shape the flow of information determine where blood gets shed, and the flow of blood in turn restricts the movement of information. Every major incident brings with it rival media footage and the roar of claim and counter-claim. The attack on a UN aid convoy near Aleppo in September, which killed 20 civilians, is a case in point. One set of videos emerged to suggest that the Syrian regime or its Russian allies were responsible. Just a few hours later, the Russians produced their own grainy film, which purported to show it was not their doing. That footage warped perceptions until what now looks like irrefutable evidence finally emerged that this was indeed a Russian or Syrian airstrike.

In this war, even supposedly “non-lethal aid,” to assist in the so-called battle of hearts and minds, can easily have lethal consequences, and the consequences of lethal force are often impossible to gauge. This is never more so than in Raqqa, the conflict’s heart of darkness. It is a year since Parliament voted to approve airstrikes on the city after the IS attacks on Paris. David Cameron, then Prime Minister, promised that bombing Raqqa would cut the head off the terrorist “snake.” Despite sustained bombardment, this has not happened. Donald Trump, US President-elect, has only promised to intensify the campaign. (In his words, “I would bomb the shit out of ‘em.”) Judging the success of airstrikes requires on-the-ground information. But there is no free journalism in Raqqa, and nobody can actually see what is going on.

I know a photojournalist from Raqqa who is the brother of one prisoner in the video. I spoke to him shortly after it appeared, and he was still in shock. Along with other exiled activists, he had been mentioned by name in the video as a handler for the “spies.” He had been writing in hostile terms about IS from the start. But since he had fled the city—he now lives in Istanbul—murdering his brother was the only way the group could get to him.

A little over six weeks before the video was released, Mohammed Emwazi, the Briton nicknamed “Jihadi John,” had been killed by a drone strike in Raqqa. Always obsessive about security, IS was now paranoid about intelligence leaks. The video was a warning to any locals who might be tempted to give up the locations of the group or its militants. Share information, it said, and we will catch you. And this will be your fate.

But it is not only IS that is prepared to sacrifice lives for the sake of changing perceptions. In the first years of Syria’s conflict, both local and foreign reporters were kidnapped and killed by all sides; independent journalism all but died. One way to get information out of rebel-held areas was to give media equipment to rebels. Over the last five years, the United States, Britain and other western governments have funnelled millions of dollars’ worth of satellite phones, cameras and laptops to young activists opposed to President Bashar al-Assad. No longer ancillary to the action, this equipment became a weapon that could capture and even choreo- graph events on the ground. It was dangerous work. A good many Syrian activists with cameras have been killed by regime forces; when the activists turned their attention to IS, scores more became targets for assassination.

Only a hundred miles east of Aleppo and a short drive south from Turkey, Raqqa rests on the north bank of the Euphrates. People have lived there for a long time. Raqqa was the site of an ancient Greek city, and after that the summer home of an early Islamic caliph. The city has been razed to the ground before. After being sacked by the Mongols in the 13th century, it ceased to exist for a while before it was revived during the Ottoman empire. In modern times, Syrian tourists ambled around its churches in the temperate weather, and viewed the striking gate which is all that remains of its old city wall. In the decade before the uprising broke out in 2011, Raqqa’s population had swollen to around half a million. Locals began to call it “Little Paris.”

Not any more. In March 2013, before IS had been established, a coalition of largely Islamist militias, including al Qaeda, ousted the Syrian army from the city. At first, freedom from Assad was invigorating. But amid factional infighting among rebel groups and airstrikes from the Syrian regime, it quickly degenerated into chaos. Nursing a visceral hatred for journalists, IS moved to throttle local and international media as it cemented itself in power. In January 2014, after an attempt by other Syrian rebel groups to gang up on IS backfired, the group decided it needed its own base in the country. Raqqa and its surrounding province became its de facto capital, and the group set about building a state: providing services for its adults, sweets and bouncy castles for its children and prisons for its political enemies. When it began blowing up Shia mosques and desecrating churches, the minorities left for Turkey. So did most of the remaining activists.

For many people, however, life under IS had its advantages—at least at first. Those left behind, many of them the poorest of the poor, were joined by refugees from elsewhere in Syria, fleeing airstrikes or anarchy in Homs and Aleppo. In 2014, activist Hamza Sattouf told me that many of his friends from Homs were flocking to Raqqa. Whereas in rebel areas, “there are a lot of thieves,” he said, in Raqqa anyone could leave their belongings lying around. The only drag were the checkpoints on the way out, where terrifyingly young militants would check your mobile phone for evidence of anything from political activity to porn.

Long before anyone else, IS understood that the real game in this new media war was to control the message. It used the internet to invite thousands of jihadis and their girlfriends from around the world to help build the new state. In summer 2014, I was in a foxhole with Kurdish militia on the border of Raqqa province. When I asked the commander if he knew anything about the IS militants attacking his position, he told me that the village on the other side of the frontline had been repopulated with Chinese fighters and their families. “The Uyghur people, I think,” he said, shrugging his shoulders quizzically.

The week before that, I had phoned a British jihadi in Raqqa called Kabir Ahmed, who waxed lyrical about the cosmopolitan feel of the city. “It’s like a dream. One day we eat Eritrean, the next we eat Pakistani.” Ahmed’s dream ended abruptly; five months after we spoke he became, according to IS media, the group’s first ever British suicide bomber. The party was soon over for his fellow jihadis, too. After IS slaughtered the American journalist James Foley and other western hostages in August 2014, President Obama took the offensive and the first US aircraft took off to hit Raqqa in September, shortly to be joined by a hastily assembled Arab coalition. A year later, they were joined by Russian planes; two months after that Britain joined the club.

F or IS militants in Raqqa, much of the day is spent scanning the sky for drones and planes. But it isn’t only foreign jihadis who live in fear. Marwan Hisham is the pseudonym of a writer from the city with whom I have been in touch for a few years. Hisham went back to Raqqa in autumn 2015 and spent months quietly taking the temperature there before getting out in January. He estimated there are at least 300,000 civilians still in the city. He said that the panic induced by aerial bombardment from a dozen countries is “unbelievable… every night there I thought I was going to die.”

The raids often begin at midnight; the cycle can go on for an hour or more. Even strikes five kilometres away are felt inside the city. If IS fighters are thought to be living in a flat, it gets obliterated and the houses around it are often badly damaged too. According to Hisham, the Russian sorties are the worst. The bombs from the coalition (the US, the UK, and other western and Middle Eastern countries) arrive from drones or planes that fly so high they cannot be seen; they fire 10 or 20 rockets in a few seconds and then disappear. The Russian planes fly lower and are visible; they sometimes bomb and circle repeatedly for up to half an hour. “It’s all about terrifying people.”

Through the fog of propaganda, it is impossible to know what the citizens of Raqqa make of all this. In the beginning IS was ostentatiously polite to the locals, says Hisham, winning it goodwill. Some people he spoke to justified working with IS on a religious basis, but mostly they were just grateful that it imposed order. IS’s rules are harsh and primitive but clear and therefore predictable. As the group finds itself squeezed, however, it has been tightening the ideological screw, trying to grow a new generation of Islamists. Courses in Sharia, once reserved for people arrested for misdemeanours, have now been extended to anyone who has a job. They consist largely of guilt-tripping local men into fighting for IS. In time, Hisham thinks that its indoctrination courses will be extended to almost everyone. “Most people are in the ‘grey area’ where they can’t decide,” is his conclusion. “IS will stay, they think, so they have to accept it.”

They have little choice. Late last year, IS began to stop everyone from leaving Raqqa except the very old or clearly sick. More recently, it has started to behead people-smugglers and display their bodies at intersections. Some fear that conscription is on the cards. The airstrikes make IS increasingly paranoid about spies. Its masked security police, known as “amnis,” hover around internet cafés and can search anyone’s phone at any time.

Soon after IS took over Raqqa, the city became an information black hole. Hungry for news, the international media fastened on a collective called “Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently” (Raqqa SL), which was working to fill the gap. At first the material its members published online was mostly culled from IS—gloomy pictures of black-clad gatherings or children with bandanas toting Kalashnikovs. Like the later salacious western tabloid coverage of IS, the difference between the group’s propaganda and the counter-propaganda was hard to spot. But Raqqa SL became more daring—publishing more of its own photos and information from inside the city.

While foreign journalists often imply that Raqqa SL’s core members are still in the city, none of the activists I know think this can be true. The space required to write and edit has been squeezed out of Raqqa. Instead, the group’s members tap friends and relatives who remain, asking questions and scouring Facebook pages. It is a perilous business—and not only for those directly involved. At first, IS left families of known activists alone but it soon began a crackdown. In 2015 it murdered the father of Hamood al-Mousa, one of the group’s leading lights. Others who may or may not have worked with Raqqa SL have been killed too. Even Turkey is no longer safe. Several members of the group have been assassinated by IS in the Turkish border city of anlurfa.

The American Committee to Protect Journalists has given Raqqa SL an award. Among Syrians, however, the group is not universally popular. In Gaziantep, a Turkish city near the Syrian border that is home to many opposition activists, I met the activist Zein al-Malazi, a long-time foe of IS. When IS was rubbing alongside rebel groups in Aleppo in 2013, she remembers, its members were so puritanical that they left the room as soon as she came in. But Raqqa SL, she told me, is generally considered a “Facebook event,” whose chief consequence is that it gets people killed. “Raqqa SL are media heroes,” she said, but “with a very small impact at the community level.”

One activist from Raqqa, who knows and likes members of the group, nonetheless accuses it of publishing publicity-seeking propaganda with no reporting depth. Like other Syrians I spoke to, he blamed the international NGOs and media who were encouraging daredevil agitprop with money and garlands. (Several activists told me that Raqqa SL receives funding from an American non-profit called Democracy Council among another western sources. Democracy Council refused to comment for this article despite several requests.) Another rebel activist I met in Gaziantep, who runs a network of confidants in neighbouring Deir ez-Zor, was unable to contain his anger. “This is bad work, what they do, and not journalism. To do that you should be safe—very safe. Anyone can connect with young guys and teenagers in a bad situation in Syria and pay them a few hundred dollars a month. Raqqa SL are responsible for all these deaths. And after a year and a half what is the impact? IS killed their people.”

One of the other men mentioned in the January execution video used to work with Basma, the now defunct media production arm of a British-led, Foreign Office and US State Department-funded agency called ARK, which moved into Turkey in 2012. Through Basma, ARK started paying young Syrians to make short films campaigning against the regime, some of which were then beamed back into the country on rebel-friendly channels or on Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya. ARK’s leading managers all have defence and security backgrounds; there are also policy advisors, “psychological operations” specialists, and former British soldiers.

While money for smart young Syrians is always welcome, one result was to fuel suspicions that mainstream journalists were under malign foreign influence. Some of those concerns appear to be well founded. Several years ago a Syrian activist sent me internal ARK briefing documents that implied the organisation was drawing on its network of Syrians to gather intelligence on Islamist groups for an unknown client. For her efforts to make these documents public she received an intimidating phone call from a local American Embassy (which she played me) and an even more intimidating visit from Turkish police. A clue to the identity of the client lay in an accompanying email apparently written by a British Lieutenant Colonel, who was forwarding those briefings to his opposite number at United States Military Command (Centcom). The email referred to “a couple of interesting documents from ARK, the contractor involved in Op VOLUTE/Project Basma in Syria,” and recommended additional funding for the project from the US. “It would be reinforcing success for comparatively modest costs,” it said.

Whatever the truth of the spying allegation, the idea that Syrian activists have been working for foreign governments has been enough to get dozens of them kidnapped and killed. A week before that January execution video was released, a well-regarded documentary maker called Naji Jerf was assassinated in Gaziantep. He had been making videos for Raqqa SL; before that, he was a manager at Basma. According to my writer contact Hisham, Raqqa SL is widely read in the city’s internet cafés. “A good deal of its information is credible, but much is also absurd.” He also accuses it of carelessness. “This is not work, not journalism; it is not professional at all. Those guys they say work for them, they pay them money to risk their lives.”

For the moment, the perception that IS has worked so hard to foster among the people of Raqqa—the belief that it is not leaving any time soon—may be valid. Over the border in Iraq, the fight is under way to free Mosul from IS hands. But at the time of writing, the Iraqi battle plan involves opening an escape corridor for IS fighters to flee to Syria—which would only reinforce its manpower in Raqqa. In any case, the group would do anything to avoid losing its Syrian capital, says Hisham—while he was there it was digging defensive trenches around the city. Last year, the prospect of American largesse ushered into existence a rebel militia called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which claims it will take the fight to IS. But the SDF is only a fig leaf for the YPG Kurdish militias, whose agenda is to keep Islamists out of their own areas. On 6th November, the Kurdish-led SDF launched a fresh military campaign with 30,000 men “to isolate Raqqa” from the North, likely because the Americans wanted them to synchronise with events in Mosul—and in return for promises of heavier weaponry and more autonomy for Kurds.

"The idea that Syrians have worked for foreign governments has got dozens of them kidnapped and killed"The Syrian rebels are not keen to be hired for the job, either. Aside from those who have become American proxies, they hate Assad much more than they do IS, and are unlikely to fight with any conviction against anyone but the Syrian army and its allies. Given that the coalition often relies on friendly Syrians on the ground to help identify IS positions, it is even possible that the US airstrike that accidentally killed 62 Syrian government troops in nearby Deir ez-Zour in September was an opportunistic attempt by rebels to re-direct American firepower on to their enemies. The Turkish government, with the help of Syrian rebel proxies, rolled its tanks into Syria to clear IS from its border in August, and in October President Erdogan floated the idea of advancing as far as Raqqa. Since the beginning of the year the Syrian army has been making its own noises about taking back Raqqa, but hasn’t made much headway. Damascus may have quietly decided that IS is now a global problem, which gives it some leverage. Instead they are focusing their efforts on dealing with the rebels in Aleppo.

At the fulcrum of Syria’s war, Raqqa has become an international card game in which all sides—from the Turks to the Syrian Kurds to the Americans to the Syrian rebels to the Syrian regime—bluff towards their own ends. Not only are the city’s people at the mercy of IS, they are in the sights of just about every country in the civilised world. In recent months, the information war has reached fever pitch as the Syrian regime redoubles its air war on rebel-held eastern Aleppo. Western-friendly media activists report that the Syrian regime and its Russian allies are deliberately targeting civilians; in turn, the strategy of the Russians is often to sow confusion. Neither side makes it clear that this is a war of two or more sides; it is as if they are living in alternate worlds. Truth has become a relative concept; everyone has an axe to grind.

The lack of independent journalism on the ground means that anyone can say anything they like. Russian officials have dismissed the idea that their warplanes might have caused a single civilian casualty. Yet at the end of September, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights counted 3,804 civilian deaths from one year of Russian strikes. The same organisation estimated that coalition airplanes had caused 611 civilian deaths in two years. The Russian toll is much higher, but since its bombing runs are spread over a much wider range of targets (the coalition is focused on IS, while the Russians are bombing IS and other rebel militias too), we can assume that a higher proportion of the coalition casualties happened in and around Raqqa.

For the first 15 months of its bombing campaign, Centcom also denied that US strikes had caused civilian deaths. Beginning in November 2015, however, it owned up that in August, three Raqqa residents had been killed in a failed attempt on the life of Junaid Hussain. Hussain, a British jihadi whose ill-judged tweets about being a terrorist super-hacker pushed him to the top of the coalition’s hit list, was killed in another strike shortly afterwards—another example of the lethal consequences of the propaganda war. In July this year, there was another incident near Manbej, then an IS outpost close to Raqqa province, in which at least 56 civilians appear to have been killed by coalition planes.

But while the Russian and Syrian onslaught on rebel-held east Aleppo is in the news every day, there was little media outcry after the Manbej bombing. There were no activists with cameras on the ground to report it (although Raqqa SL issued a statement castigating the coalition for causing so many deaths). IS produces its own videos of the aftermath of bombings in Raqqa, but no one in the outside world pays them any attention. The danger is that the images of death and destruction that appear on our television screens exist in a kind of feedback loop—giving us the news that our governments want us to hear, and leaving out what they don’t.

Meanwhile, Raqqa is being pounded by all sides. In August, the Guardian reported that Kadiza Sultana, one of three schoolgirls from Bethnal Green who joined IS in 2015, had been killed on 22nd June. From sources in Raqqa, her family were told that she had been living in a flat above a “financial office” in the city which had been hit by a Russian airstrike. But is that right? The airstrikes on Raqqa at that time were identified by Raqqa SL as Russian. Yet as an opposition media group, Raqqa SL might be more inclined to blame attacks on the regime-supporting Russians. The more circumspect Syrian Observatory cannot say who carried out the strikes. Centcom’s data for that night referred to an attack by US or UK airplanes on a “finance center” in Raqqa. It seems likely Sultana was killed as collateral damage from an American bomb or a British Reaper drone. The independent monitoring group AirWars told me that if Sultana’s flat really was above that IS financial office, then “it’s almost certain the coalition was responsible.”

Nothing coming out of Syria can be taken on trust, and the people left in Raqqa have nobody to plead their case. With their eyes fixed on the afterlife, IS’s zealous international volunteers are not deterred by the prospect of martyrdom. But many of the young locals have signed up for checkpoint duty for money or status. They want to get on and live. Around 20 people from Marwan Hisham’s neighbourhood alone, however, have already been killed fighting for IS. At the end of October the Syrian Observatory estimated that the bodies of 300 Syrian children (so-called “Cubs of the Caliphate”) had been returned to Raqqa, having been killed in IS’s defence of Mosul.

The photojournalist whose brother died in the January video told me that while he sympathised with France after the Paris attacks, killing people from the air was hardly the answer. “In Raqqa there are a lot of French IS fighters, but we don’t say all French people are jihadis. In Raqqa, too, most people are innocent.” Raqqa’s tragedy is that it has become a punchbag for everyone’s impotent frustrations about IS. That situation might only get worse under President Trump.

Using expendable Syrians for media and intelligence may yet have far-reaching effects. Marwan Hisham says the people of his native city are being backed into a corner. “I feel very sad. I know those people, I was born there, lived there all my life—they [the major powers] are not giving them any choice. Now it’s all about revenge… In the worst-case scenario, the people of Raqqa will join IS. At the very least they will hate the west, and they will hate the world.”